Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Marketplace radio had a peculiar piece asking what the world would have looked like if NAFTA never had been signed. The piece is odd because it dismisses job concerns associated with NAFTA by telling readers that automation (i.e. productivity growth) has been far more important in costing jobs.

“As in, ATMs replacing bankers, robots displacing welders. Automation is a very old story that goes back 250 years, but it has really picked up in the last couple decades.

“‘We economic developers have an old joke,’ said Charles Hayes of the Research Triangle Regional Partnership in an interview with Marketplace in 2010. ‘The manufacturing facility of the future will employ two people: one will be a man, and one will be a dog. And the man will be there to feed the dog. And the dog will be there to make sure the man doesn’t touch the equipment.’

“Ouch. But it turns out technology replaced workers in the course of reporting this very story.”

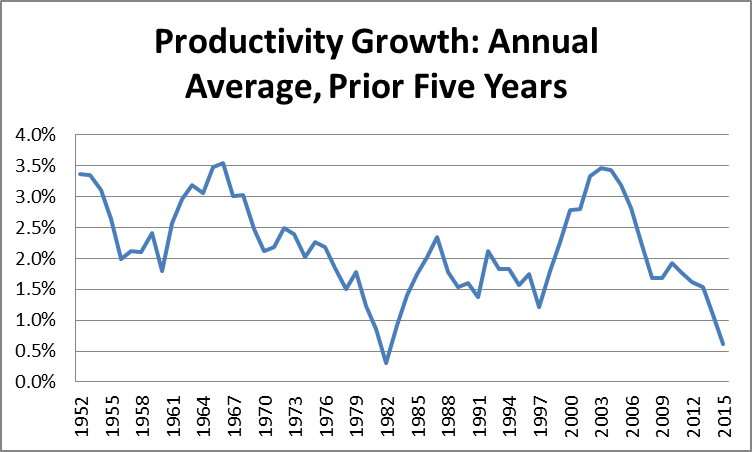

Actually, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us the opposite. Productivity growth did pick up from 1995 to 2005, rising back to its 1947 to 1973 Golden Age pace (a period of low unemployment and rapidly rising wages), but has slowed sharply in the last dozen years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While more rapid productivity growth would allow for faster wage and overall economic growth, no one has a very clear path for raising the rate of productivity growth. It is strange that Marketplace thinks our problem is a too rapid pace of productivity growth.

The piece is right in saying that the jobs impact of NAFTA was relatively limited. Certainly trade with China displaced many more workers. NAFTA may nonetheless have had a negative impact on the wages of many manufacturing workers. It made the threat to move operations to Mexico far more credible and many employers took advantage of this opportunity to discourage workers from joining unions and to make wage concessions. It’s surprising that the piece did not discuss this effect of NAFTA.

Marketplace radio had a peculiar piece asking what the world would have looked like if NAFTA never had been signed. The piece is odd because it dismisses job concerns associated with NAFTA by telling readers that automation (i.e. productivity growth) has been far more important in costing jobs.

“As in, ATMs replacing bankers, robots displacing welders. Automation is a very old story that goes back 250 years, but it has really picked up in the last couple decades.

“‘We economic developers have an old joke,’ said Charles Hayes of the Research Triangle Regional Partnership in an interview with Marketplace in 2010. ‘The manufacturing facility of the future will employ two people: one will be a man, and one will be a dog. And the man will be there to feed the dog. And the dog will be there to make sure the man doesn’t touch the equipment.’

“Ouch. But it turns out technology replaced workers in the course of reporting this very story.”

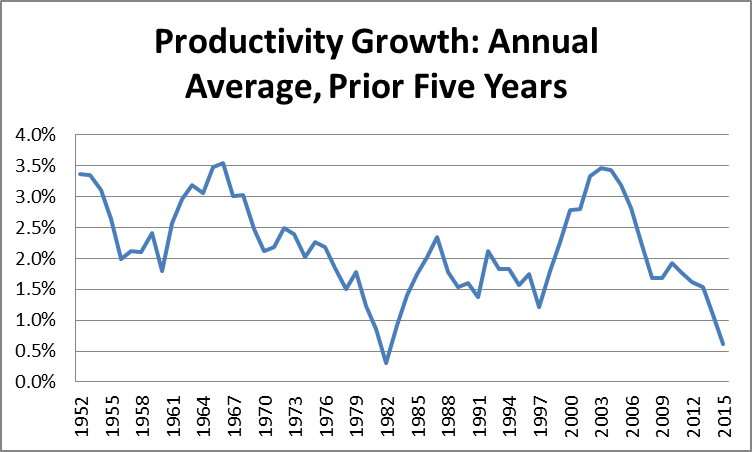

Actually, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us the opposite. Productivity growth did pick up from 1995 to 2005, rising back to its 1947 to 1973 Golden Age pace (a period of low unemployment and rapidly rising wages), but has slowed sharply in the last dozen years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While more rapid productivity growth would allow for faster wage and overall economic growth, no one has a very clear path for raising the rate of productivity growth. It is strange that Marketplace thinks our problem is a too rapid pace of productivity growth.

The piece is right in saying that the jobs impact of NAFTA was relatively limited. Certainly trade with China displaced many more workers. NAFTA may nonetheless have had a negative impact on the wages of many manufacturing workers. It made the threat to move operations to Mexico far more credible and many employers took advantage of this opportunity to discourage workers from joining unions and to make wage concessions. It’s surprising that the piece did not discuss this effect of NAFTA.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition had a segment on Republican efforts to repeal Obamacare which reported on the desire of many Republican members of Congress to reduce the number of essential health benefits that must be covered by insurance. While the piece noted that part of the reason for the required benefits is to ensure people are covered in important areas, this is probably the less important reason for imposing requirements.

If people are allowed to pick and choose what conditions get covered, many more healthy people may opt for plans that cover few conditions and cost very little. If this happens, then plans that offer more comprehensive coverage will have a less healthy pool of beneficiaries, and therefore have to charge high fees. This will make insurance unaffordable for the people who most need it.

Morning Edition had a segment on Republican efforts to repeal Obamacare which reported on the desire of many Republican members of Congress to reduce the number of essential health benefits that must be covered by insurance. While the piece noted that part of the reason for the required benefits is to ensure people are covered in important areas, this is probably the less important reason for imposing requirements.

If people are allowed to pick and choose what conditions get covered, many more healthy people may opt for plans that cover few conditions and cost very little. If this happens, then plans that offer more comprehensive coverage will have a less healthy pool of beneficiaries, and therefore have to charge high fees. This will make insurance unaffordable for the people who most need it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s great that there are so many jobs for mind readers in the media. This morning Tamara Keith used her talents in this area to tell listeners that members of the Republican “Freedom Caucus” in the House “believe” that reducing the areas of mandated coverage is the key to reducing the cost of insurance.

It’s good that we have someone who can tell us what these Freedom Caucus members really believe. Otherwise, many people might think that they were trying to reduce the areas of mandated coverage in order to allow healthy people to avoid subsidizing less healthy people.

Someone in good health can buy a plan with very little coverage, since odds are they will not need coverage for most conditions. These plans would be relatively low cost, since they are paying out little in benefits. On the other hand, plans that did cover more conditions would be extremely expensive and unaffordable to most people. If we didn’t have a NPR mind reader to tell us otherwise, we might think that this is the situation that the Freedom Caucus members are trying to bring about.

It’s great that there are so many jobs for mind readers in the media. This morning Tamara Keith used her talents in this area to tell listeners that members of the Republican “Freedom Caucus” in the House “believe” that reducing the areas of mandated coverage is the key to reducing the cost of insurance.

It’s good that we have someone who can tell us what these Freedom Caucus members really believe. Otherwise, many people might think that they were trying to reduce the areas of mandated coverage in order to allow healthy people to avoid subsidizing less healthy people.

Someone in good health can buy a plan with very little coverage, since odds are they will not need coverage for most conditions. These plans would be relatively low cost, since they are paying out little in benefits. On the other hand, plans that did cover more conditions would be extremely expensive and unaffordable to most people. If we didn’t have a NPR mind reader to tell us otherwise, we might think that this is the situation that the Freedom Caucus members are trying to bring about.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When we have a guy in the White House who imagines that millions of non-citizens are illegally voting and going undetected and that the former president tapped his phones, we know we are in the crazy season. Therefore it is not surprising to see George Will touting some bizarre principle of “universal access” to health insurance in his Washington Post column. There is no price tag associated with Will’s “access” so an insurance policy that is completely unaffordable to almost everyone would satisfy Will’s moral principle.

This is not a philosophical debate over various hypotheticals in the world. Obamacare was designed so that plans were mandated to cover a large range of conditions. This meant that the vast majority of the population, who don’t have expensive health care conditions, were subsidizing the relatively small group of people who do.

However, if we allow insurers to slice and dice plans, so that people who don’t suffer from certain conditions and are unlikely to in the future (e.g. women will not get prostate cancer and men won’t get pregnant) don’t have to pay the costs for those who do, then we can end up with a situation where some plans only have people with expensive health conditions and therefore are very expensive.

We could envision, for example, that plans would exclude pancreatic cancer, which is believed to be largely hereditary. People without a history of pancreatic cancer in their family would face little risk getting insurance that excludes this coverage. On the other hand, those with a history would be able to buy a plan that covered pancreatic cancer, but they would just have to pay an extremely high price since the insurers would know there was a high probability that anyone buying the plan would get pancreatic cancer.

In George Will’s world, all is good, since the principle of universal access has been met. Of course, in the world where the rest of us live, almost no one with a family history of pancreatic cancer would actually have health insurance.

When we have a guy in the White House who imagines that millions of non-citizens are illegally voting and going undetected and that the former president tapped his phones, we know we are in the crazy season. Therefore it is not surprising to see George Will touting some bizarre principle of “universal access” to health insurance in his Washington Post column. There is no price tag associated with Will’s “access” so an insurance policy that is completely unaffordable to almost everyone would satisfy Will’s moral principle.

This is not a philosophical debate over various hypotheticals in the world. Obamacare was designed so that plans were mandated to cover a large range of conditions. This meant that the vast majority of the population, who don’t have expensive health care conditions, were subsidizing the relatively small group of people who do.

However, if we allow insurers to slice and dice plans, so that people who don’t suffer from certain conditions and are unlikely to in the future (e.g. women will not get prostate cancer and men won’t get pregnant) don’t have to pay the costs for those who do, then we can end up with a situation where some plans only have people with expensive health conditions and therefore are very expensive.

We could envision, for example, that plans would exclude pancreatic cancer, which is believed to be largely hereditary. People without a history of pancreatic cancer in their family would face little risk getting insurance that excludes this coverage. On the other hand, those with a history would be able to buy a plan that covered pancreatic cancer, but they would just have to pay an extremely high price since the insurers would know there was a high probability that anyone buying the plan would get pancreatic cancer.

In George Will’s world, all is good, since the principle of universal access has been met. Of course, in the world where the rest of us live, almost no one with a family history of pancreatic cancer would actually have health insurance.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT might have wrongly lead readers to believe that presidents prior to Donald Trump supported free trade in an article noting his refusal to go along with a G-20 statement proclaiming the importance of free trade. This is not true.

Past administrations of both parties have been vigorous supporters of longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. These protections can raise the price of protected items by factors of ten or even a hundred, making them equivalent to tariffs of 1000 and 10,000 percent. These protections lead to the same sorts of economic distortion and corruption that economists would predict from tariffs of this size.

Past administrations have also supported barriers that protect our most highly paid professionals, such as doctors and dentists, from foreign competition. They apparently believed that these professionals lack the skills necessary to compete in the global economy and therefore must be protected from the international competition. The result is that the rest of us pay close to $100 billion more each year for our medical bills ($700 per family).

The NYT might have wrongly lead readers to believe that presidents prior to Donald Trump supported free trade in an article noting his refusal to go along with a G-20 statement proclaiming the importance of free trade. This is not true.

Past administrations of both parties have been vigorous supporters of longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. These protections can raise the price of protected items by factors of ten or even a hundred, making them equivalent to tariffs of 1000 and 10,000 percent. These protections lead to the same sorts of economic distortion and corruption that economists would predict from tariffs of this size.

Past administrations have also supported barriers that protect our most highly paid professionals, such as doctors and dentists, from foreign competition. They apparently believed that these professionals lack the skills necessary to compete in the global economy and therefore must be protected from the international competition. The result is that the rest of us pay close to $100 billion more each year for our medical bills ($700 per family).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson put forward what would ordinarily be a very reasonable proposal on Medicaid and Medicare in his column today. He suggested that the federal government take over the portion of Medicaid that deals with low-income elderly and fold it into the Medicare program, while leaving states with full responsibility for dealing with the part of Medicaid that deals with low-income families below retirement age.

While he is right that this sort of consolidation could likely reduce costs and prevent seniors from falling between the cracks in the two systems, there is a basic problem with turning Medicaid over to the states. There are a number of states controlled by Republicans where there is little or no interest in providing health care for low-income families.

This means that if Medicaid were turned completely over to the states, millions of low-income families would lose access to health care. For this reason, people who want to see low-income families get health care, which is the purpose of Medicaid, want to see the program remain partly under the federal government’s control.

Robert Samuelson put forward what would ordinarily be a very reasonable proposal on Medicaid and Medicare in his column today. He suggested that the federal government take over the portion of Medicaid that deals with low-income elderly and fold it into the Medicare program, while leaving states with full responsibility for dealing with the part of Medicaid that deals with low-income families below retirement age.

While he is right that this sort of consolidation could likely reduce costs and prevent seniors from falling between the cracks in the two systems, there is a basic problem with turning Medicaid over to the states. There are a number of states controlled by Republicans where there is little or no interest in providing health care for low-income families.

This means that if Medicaid were turned completely over to the states, millions of low-income families would lose access to health care. For this reason, people who want to see low-income families get health care, which is the purpose of Medicaid, want to see the program remain partly under the federal government’s control.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A front page Washington Post piece profiled Tamara Estes, a supporter of Donald Trump who is anxious to see undocumented aliens deported, along with a neighboring family, the Corrals. The parents in the Corral family entered the country illegally, while the children were born in the United States and are therefore U.S. citizens.

In describing the situation of Ms. Estes, the piece tells readers that she earns $24,000 a year driving a school bus part-time. It then reports that she does not have health care insurance:

“She earns a bit too much to qualify for most government assistance but too little to buy health insurance, with its high monthly premiums and impossible deductibles.”

Actually, her income would qualify her for substantial assistance in buying health care insurance. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s premium calculator, the government would pay a subsidy of $548 a month for a $678 a month silver plan. This would leave her with a monthly payment of $130.

It is possible that Ms. Estes would still decide not to buy the insurance at this price, but it is wrong to say that she does not qualify for government assistance. The subsidy she could get on her insurance is considerably larger than the TANF benefit that a family of three would receive in Texas.

The Post should have provided correct information to readers on this issue. It might also have been useful to question Ms. Estes further on why she opted not to take advantage of the assistance available to her.

Addendum

I should have also mentioned that the Bronze plan would cost Ms. Estes $70 a month according to the Kaiser calculator. This also comes free wellness exams and other preventive care.

A front page Washington Post piece profiled Tamara Estes, a supporter of Donald Trump who is anxious to see undocumented aliens deported, along with a neighboring family, the Corrals. The parents in the Corral family entered the country illegally, while the children were born in the United States and are therefore U.S. citizens.

In describing the situation of Ms. Estes, the piece tells readers that she earns $24,000 a year driving a school bus part-time. It then reports that she does not have health care insurance:

“She earns a bit too much to qualify for most government assistance but too little to buy health insurance, with its high monthly premiums and impossible deductibles.”

Actually, her income would qualify her for substantial assistance in buying health care insurance. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s premium calculator, the government would pay a subsidy of $548 a month for a $678 a month silver plan. This would leave her with a monthly payment of $130.

It is possible that Ms. Estes would still decide not to buy the insurance at this price, but it is wrong to say that she does not qualify for government assistance. The subsidy she could get on her insurance is considerably larger than the TANF benefit that a family of three would receive in Texas.

The Post should have provided correct information to readers on this issue. It might also have been useful to question Ms. Estes further on why she opted not to take advantage of the assistance available to her.

Addendum

I should have also mentioned that the Bronze plan would cost Ms. Estes $70 a month according to the Kaiser calculator. This also comes free wellness exams and other preventive care.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The politicians who are trying to cut Social Security and Medicare know that these programs are incredibly popular across the political spectrum. For this reason they typically use euphemisms when referring to plans to cut the benefits they provide, like calling for “reform,” “modernization,” or “slowing the growth.”

It is understandable that politicians pushing an unpopular agenda would try to mislead people about their actions, but it’s not clear why the NYT is playing the same game, telling readers in an article on the Trump budget:

“But the early reaction from members of his party on Capitol Hill was muted at best, reflecting in part the discomfort among many of the party’s leaders with a budget that makes no progress on tackling the growth of entitlements.”

The reference to “no progress on tackling the growth of entitlements” is the NYT’s way of saying the budget doesn’t cut Social Security and Medicare. This should be an easy one, it’s shorter and more informative to just describe the issue directly.

The politicians who are trying to cut Social Security and Medicare know that these programs are incredibly popular across the political spectrum. For this reason they typically use euphemisms when referring to plans to cut the benefits they provide, like calling for “reform,” “modernization,” or “slowing the growth.”

It is understandable that politicians pushing an unpopular agenda would try to mislead people about their actions, but it’s not clear why the NYT is playing the same game, telling readers in an article on the Trump budget:

“But the early reaction from members of his party on Capitol Hill was muted at best, reflecting in part the discomfort among many of the party’s leaders with a budget that makes no progress on tackling the growth of entitlements.”

The reference to “no progress on tackling the growth of entitlements” is the NYT’s way of saying the budget doesn’t cut Social Security and Medicare. This should be an easy one, it’s shorter and more informative to just describe the issue directly.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión