The NYT had an article discussing various efforts to deal with companies shifting profits overseas to avoid paying the corporate income tax. The piece implies that we don’t know how to ensure that companies pay taxes on foreign profits.

Actually, it is not hard to design a system where companies cannot avoid paying taxes on their foreign profits. If corporations were required to turn over an amount of non-voting shares equal to the targeted tax rate (e.g. if we want taxes to be equal to 25 percent of profits, then the non-voting shares should be equal to 25 percent of the total), then it would be almost impossible for companies to escape their tax liability.

Under this system, the non-voting shares would be treated the same way as voting shares in terms of payouts. If a company paid a $2 dividend on its voting shares, then the government’s shares would also get a $2 dividend. If it bought back 10 percent of its shares at $100 a share, it will also buy back 10 percent of the government’s shares at $100 a share.

Under this system, there is basically no way for a company to avoid its tax obligations unless it also rips off its own shareholders. In this case, it would be outright fraud and the shareholders would have a large interest in cracking down on its top management.

It understandable that those who don’t want corporations to pay income taxes would be opposed to this sort of non-voting shares system, but it is wrong to say that we don’t know how to collect the corporate income tax.

The NYT had an article discussing various efforts to deal with companies shifting profits overseas to avoid paying the corporate income tax. The piece implies that we don’t know how to ensure that companies pay taxes on foreign profits.

Actually, it is not hard to design a system where companies cannot avoid paying taxes on their foreign profits. If corporations were required to turn over an amount of non-voting shares equal to the targeted tax rate (e.g. if we want taxes to be equal to 25 percent of profits, then the non-voting shares should be equal to 25 percent of the total), then it would be almost impossible for companies to escape their tax liability.

Under this system, the non-voting shares would be treated the same way as voting shares in terms of payouts. If a company paid a $2 dividend on its voting shares, then the government’s shares would also get a $2 dividend. If it bought back 10 percent of its shares at $100 a share, it will also buy back 10 percent of the government’s shares at $100 a share.

Under this system, there is basically no way for a company to avoid its tax obligations unless it also rips off its own shareholders. In this case, it would be outright fraud and the shareholders would have a large interest in cracking down on its top management.

It understandable that those who don’t want corporations to pay income taxes would be opposed to this sort of non-voting shares system, but it is wrong to say that we don’t know how to collect the corporate income tax.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran an article about a new study from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) comparing the pay of federal government employees with their counterparts in the private sector. The study found that less educated employees tend to earn more in the federal government than in the private sector, while more educated workers on average earn somewhat less. On average, it found there was a small pay premium for federal employees. The article also notes several other studies with different findings, most importantly an analysis from the Labor Department that found the pay of federal employees lags the private sector by 38 percent.

It is worth noting the main reason for the difference in the two studies. The CBO analysis calculates private sector pay by looking at general categories of workers based on experience and education. By contrast, the Labor Department analysis tries to match up specific tasks performed by federal employees with their counterparts in the private sector. For example, the pay of a biologist working at the National Institutes of Health would be compared with the pay of a biologist working in the pharmaceutical industry. If done accurately, this methodology should provide a more accurate comparison.

The Washington Post ran an article about a new study from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) comparing the pay of federal government employees with their counterparts in the private sector. The study found that less educated employees tend to earn more in the federal government than in the private sector, while more educated workers on average earn somewhat less. On average, it found there was a small pay premium for federal employees. The article also notes several other studies with different findings, most importantly an analysis from the Labor Department that found the pay of federal employees lags the private sector by 38 percent.

It is worth noting the main reason for the difference in the two studies. The CBO analysis calculates private sector pay by looking at general categories of workers based on experience and education. By contrast, the Labor Department analysis tries to match up specific tasks performed by federal employees with their counterparts in the private sector. For example, the pay of a biologist working at the National Institutes of Health would be compared with the pay of a biologist working in the pharmaceutical industry. If done accurately, this methodology should provide a more accurate comparison.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Donald Trump gets lots of things wrong, but he doesn’t necessarily get everything wrong. On the link between budget deficits and trade deficits, Trump might be closer to the mark than the NYT.

The NYT rightly took Donald Trump to task for being lost in his trade policy. During his campaign Trump railed against NAFTA and repeatedly complained about China’s currency “manipulation.” Now that he is in the White House it is still not clear exactly what he hopes to do with NAFTA.

In the case of China, he has decided he is now good friends with China’s president Xi Jinping after meeting with him earlier in the month. Trump apparently decided it would be rude to raise the currency issue with his new friend and instead settled for some Chinese trademarks for his daughters’ clothing line.

Trump definitely deserves some criticism for this reversal, but the NYT editorial goes a bit overboard in telling readers that Trump’s tax cut plan will make the trade deficit worse:

“Those tax cuts might increase growth somewhat, but history and many experts tell us it is far more likely that the tax cuts would explode the deficit and drive up interest rates as the federal government is forced to increase borrowing. Investors from around the world would then pour money into Treasury bonds, bidding up the value of the dollar, which would increase the trade deficit — $502 billion last year — as American exports become more expensive in the rest of the world and imports become cheaper. This in turn could cost jobs. Economists say that’s exactly what happened in the 1980s when the Reagan administration and Congress drove up the federal deficit through tax cuts and increased military spending.”

Actually, there is a very weak relationship between the budget deficit, interest rates, and the value of the dollar. While the dollar did rise a great deal in the early 1980s, arguably theis was at least as much due to Paul Volcker’s interst rate policy at the Fed as the budget deficit. The dollar fell sharply in the second half of the decade following the Plaza Accord, in which our major trading partners agreed to try to bring down the value of the dollar. This is in spite of the fact that there was little reduction in the structural deficit over this period.

The biggest run-up in the value of the dollar occurred in the late 1990s, when the budget deficit was turning into a surplus, following the I.M.F.’s bailout of the countries of East Asia, after the 1997 financial crisis. Developing countries in the region and around the world began to accumulate massive amounts of reserves in order to avoid being in the same situation as the countries of East Asia. This accumulation of reserves caused the dollar to rise by more than 30 percent against the currencies of U.S. trading partners.

The trade deficit exploded in response, eventually reaching almost 6 percent of GDP in 2005 and 2006. The budget deficits of the 2000s almost certainly increased employment by creating demand in a context where there was a worldwide saving glut.

Given this history, and the fact that the U.S. economy arguably still has a considerable amount of excess capacity (the employment-to-population ratio for prime-age workers is still down by 2 percentage points from pre-recession levels and 4 percentage points from 2000 levels), it is far from clear that an increase in the budget deficit will lead to a higher dollar and a larger trade deficit.

Note: Typos have been corrected from an earlier version.

Donald Trump gets lots of things wrong, but he doesn’t necessarily get everything wrong. On the link between budget deficits and trade deficits, Trump might be closer to the mark than the NYT.

The NYT rightly took Donald Trump to task for being lost in his trade policy. During his campaign Trump railed against NAFTA and repeatedly complained about China’s currency “manipulation.” Now that he is in the White House it is still not clear exactly what he hopes to do with NAFTA.

In the case of China, he has decided he is now good friends with China’s president Xi Jinping after meeting with him earlier in the month. Trump apparently decided it would be rude to raise the currency issue with his new friend and instead settled for some Chinese trademarks for his daughters’ clothing line.

Trump definitely deserves some criticism for this reversal, but the NYT editorial goes a bit overboard in telling readers that Trump’s tax cut plan will make the trade deficit worse:

“Those tax cuts might increase growth somewhat, but history and many experts tell us it is far more likely that the tax cuts would explode the deficit and drive up interest rates as the federal government is forced to increase borrowing. Investors from around the world would then pour money into Treasury bonds, bidding up the value of the dollar, which would increase the trade deficit — $502 billion last year — as American exports become more expensive in the rest of the world and imports become cheaper. This in turn could cost jobs. Economists say that’s exactly what happened in the 1980s when the Reagan administration and Congress drove up the federal deficit through tax cuts and increased military spending.”

Actually, there is a very weak relationship between the budget deficit, interest rates, and the value of the dollar. While the dollar did rise a great deal in the early 1980s, arguably theis was at least as much due to Paul Volcker’s interst rate policy at the Fed as the budget deficit. The dollar fell sharply in the second half of the decade following the Plaza Accord, in which our major trading partners agreed to try to bring down the value of the dollar. This is in spite of the fact that there was little reduction in the structural deficit over this period.

The biggest run-up in the value of the dollar occurred in the late 1990s, when the budget deficit was turning into a surplus, following the I.M.F.’s bailout of the countries of East Asia, after the 1997 financial crisis. Developing countries in the region and around the world began to accumulate massive amounts of reserves in order to avoid being in the same situation as the countries of East Asia. This accumulation of reserves caused the dollar to rise by more than 30 percent against the currencies of U.S. trading partners.

The trade deficit exploded in response, eventually reaching almost 6 percent of GDP in 2005 and 2006. The budget deficits of the 2000s almost certainly increased employment by creating demand in a context where there was a worldwide saving glut.

Given this history, and the fact that the U.S. economy arguably still has a considerable amount of excess capacity (the employment-to-population ratio for prime-age workers is still down by 2 percentage points from pre-recession levels and 4 percentage points from 2000 levels), it is far from clear that an increase in the budget deficit will lead to a higher dollar and a larger trade deficit.

Note: Typos have been corrected from an earlier version.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, it’s Groundhog Day. Republicans are once again claiming that tax cuts will spur enough economic growth to pay for themselves. Well, old-timers like myself remember Round I and Round II when we tried this grand experiment. It didn’t work.

Round I was under President Reagan when he put in big tax cuts at the start of the presidency. These tax cuts were supposed to lead to a growth surge which would cover the costs of the tax cuts. Not quite, the deficit soared and the debt-to-GDP ratio went from 25.5 percent of GDP at the end of 1980 to 39.8 percent of GDP at the end of 1988. (It rose further to 46.6 percent of GDP by the end of the first President Bush’s term.)

Round II were the tax cuts put in place by George W. Bush. At the start of the Bush II administration the ratio of debt to GDP was 33.6 percent. It rose to 39.3 percent by the end of 2008.

In addition to these two big lab experiments with the national economy, we also have a large body of economic research on the issue. This research is well summarized in a study done by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) back in 2005 when it was headed by Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a Republican economist who had served as the head of George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers.

I commented on this study a few years back:

“In a model that examined the effects of a 10% reduction in all federal individual income tax rates, the economy was slightly larger in the first five years after the tax cut and slightly smaller in the five years that followed. In this case, using dynamic scoring showed the tax cut costing more revenue than in the methodology the CBO currently uses.

“The CBO did find that dynamic scoring of the tax cut could have some positive effects if coupled with other policies. In one set of models, policymakers assumed that taxes were raised after 10 years. This led the government to raise more tax revenue in the first 10 years because people knew that they would be taxed more later, so they worked more.”

In short, Holtz-Eakin considered the extent to which tax cuts could plausibly be said to boost growth and found that they had very limited impact on the deficit. The one partial exception, in which growth offset around 30 percent of the revenue lost, was in a story where people expected taxes to rise in the future. In this case, people worked and saved more in the low-tax period with the idea that they would work and save less in the higher tax period in the future.

That is not a story of increasing growth, but rather moving it forward. I doubt that any of the Republicans pushing tax cuts want to tell people that they better work more now because we will tax you more in the future. But that is the logic of the scenario where growth recaptures at least some of the lost revenue.

Having said all this, let me add my usual point. The debt-to-GDP ratio tells us almost nothing. We should be far more interested the ratio of debt service to GDP (now near a post war low of 0.8 percent).

Also, if we are concerned about future obligations we are creating for our children we must look at patent and copyright monopolies. These are in effect privately imposed taxes that the government allows private companies to charge as incentive for innovation and creative work. The size of these patent rents in pharmaceuticals alone is approaching $400 billion. This is more than 2 percent of GDP and more than 10 percent of all federal revenue. In other words, it is a huge burden that honest people cannot ignore.

Yes, it’s Groundhog Day. Republicans are once again claiming that tax cuts will spur enough economic growth to pay for themselves. Well, old-timers like myself remember Round I and Round II when we tried this grand experiment. It didn’t work.

Round I was under President Reagan when he put in big tax cuts at the start of the presidency. These tax cuts were supposed to lead to a growth surge which would cover the costs of the tax cuts. Not quite, the deficit soared and the debt-to-GDP ratio went from 25.5 percent of GDP at the end of 1980 to 39.8 percent of GDP at the end of 1988. (It rose further to 46.6 percent of GDP by the end of the first President Bush’s term.)

Round II were the tax cuts put in place by George W. Bush. At the start of the Bush II administration the ratio of debt to GDP was 33.6 percent. It rose to 39.3 percent by the end of 2008.

In addition to these two big lab experiments with the national economy, we also have a large body of economic research on the issue. This research is well summarized in a study done by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) back in 2005 when it was headed by Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a Republican economist who had served as the head of George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers.

I commented on this study a few years back:

“In a model that examined the effects of a 10% reduction in all federal individual income tax rates, the economy was slightly larger in the first five years after the tax cut and slightly smaller in the five years that followed. In this case, using dynamic scoring showed the tax cut costing more revenue than in the methodology the CBO currently uses.

“The CBO did find that dynamic scoring of the tax cut could have some positive effects if coupled with other policies. In one set of models, policymakers assumed that taxes were raised after 10 years. This led the government to raise more tax revenue in the first 10 years because people knew that they would be taxed more later, so they worked more.”

In short, Holtz-Eakin considered the extent to which tax cuts could plausibly be said to boost growth and found that they had very limited impact on the deficit. The one partial exception, in which growth offset around 30 percent of the revenue lost, was in a story where people expected taxes to rise in the future. In this case, people worked and saved more in the low-tax period with the idea that they would work and save less in the higher tax period in the future.

That is not a story of increasing growth, but rather moving it forward. I doubt that any of the Republicans pushing tax cuts want to tell people that they better work more now because we will tax you more in the future. But that is the logic of the scenario where growth recaptures at least some of the lost revenue.

Having said all this, let me add my usual point. The debt-to-GDP ratio tells us almost nothing. We should be far more interested the ratio of debt service to GDP (now near a post war low of 0.8 percent).

Also, if we are concerned about future obligations we are creating for our children we must look at patent and copyright monopolies. These are in effect privately imposed taxes that the government allows private companies to charge as incentive for innovation and creative work. The size of these patent rents in pharmaceuticals alone is approaching $400 billion. This is more than 2 percent of GDP and more than 10 percent of all federal revenue. In other words, it is a huge burden that honest people cannot ignore.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article reporting on how the Pew Research Center had discovered work done by the Economic Policy Institute for a quarter century (the middle class is hurting). At one point the piece compares the United States with France and Germany:

“The United States, including the middle class, has a higher median income than nearly all of Europe, even if the Continent is catching up. The median household income in the United States was $52,941 after taxes in 2010, compared with $41,047 in Germany and $41,076 in France.”

When making such comparisons it is important to note that people in Europe work many few hours than people in the United States. Five or six weeks a year of vacation are standard. In addition, these countries all mandate paid sick days and paid family leave.

According to the OECD, the length of the average work year in the United States in 2015 was 1790 hours. It was 1482 hours in France (17 percent fewer hours) and just 1371 hours (23 percent fewer hours) in Germany. While these comparisons are not perfect (there are measurement issues) it is clear that people in these countries and the rest of Europe are working considerably fewer hours than people in the United States in large part as a conscious choice. This should be noted in any effort to compare them.

The NYT had an article reporting on how the Pew Research Center had discovered work done by the Economic Policy Institute for a quarter century (the middle class is hurting). At one point the piece compares the United States with France and Germany:

“The United States, including the middle class, has a higher median income than nearly all of Europe, even if the Continent is catching up. The median household income in the United States was $52,941 after taxes in 2010, compared with $41,047 in Germany and $41,076 in France.”

When making such comparisons it is important to note that people in Europe work many few hours than people in the United States. Five or six weeks a year of vacation are standard. In addition, these countries all mandate paid sick days and paid family leave.

According to the OECD, the length of the average work year in the United States in 2015 was 1790 hours. It was 1482 hours in France (17 percent fewer hours) and just 1371 hours (23 percent fewer hours) in Germany. While these comparisons are not perfect (there are measurement issues) it is clear that people in these countries and the rest of Europe are working considerably fewer hours than people in the United States in large part as a conscious choice. This should be noted in any effort to compare them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It would have been worth including this point in an interesting column by Gretchen Morgenson noting how bank regulators remain close to the industry they regulate. The point is straightforward. If banks can make profits by writing deceptive contracts and finding ways to trick consumers, then they will devote resources to this effort, instead of concentrating on providing better services and reducing costs.

From the standpoint of the economy, devoting resources to ripping off consumers is a complete waste. It simply redistributes money from the rest of society to the banks. For this reason, people who care about economic growth should support measures that prevent predatory practices by the financial industry.

It would have been worth including this point in an interesting column by Gretchen Morgenson noting how bank regulators remain close to the industry they regulate. The point is straightforward. If banks can make profits by writing deceptive contracts and finding ways to trick consumers, then they will devote resources to this effort, instead of concentrating on providing better services and reducing costs.

From the standpoint of the economy, devoting resources to ripping off consumers is a complete waste. It simply redistributes money from the rest of society to the banks. For this reason, people who care about economic growth should support measures that prevent predatory practices by the financial industry.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

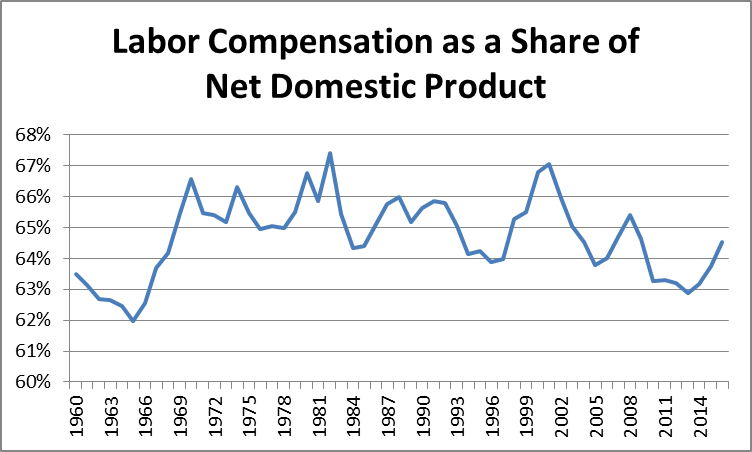

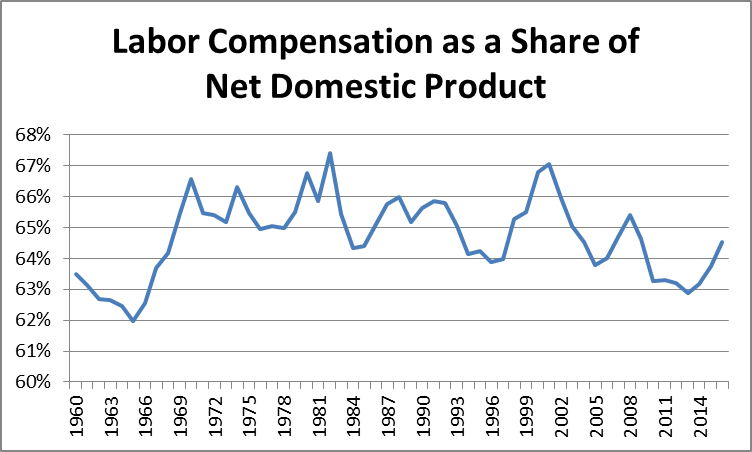

I see Noah Smith is struggling to explain “the mystery of labor’s falling share of GDP.” At the risk of jeopardizing good paying jobs for people with PhDs in economics, let me suggest that there is no mystery to explain.

Noah’s piece features a graph showing the labor share of GDP declining from a range of 64 to 65 percent in the 1960s and early 1970s to just over 60 percent in the most recent data. He then gives us several possible explanations for this drop. Let me give an alternative one, there was no drop or at least not much of one.

Suppose we look at the labor share of net domestic product. This is GDP after removing depreciation. This makes sense since deprecation is not something to be divided by labor and capital. It is the amount of output needed to replace worn out plant and equipment. The story since 1960 is below. (For those wanted to check the numbers, labor compensation comes from NIPA Table 1.10, Line 2; NDP from Table 1.7.5, Line 30.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

As we can see, there is no pattern of decline over the last five decades. In fact, the labor share of net domestic product is higher today than it was in the sixties. The labor share did fall sharply in the Great Recession, but this seems easy to attribute to the extraordinary weakness of the labor market. The share is now recovering and my bet is, that if the Fed can be prevented from slamming on the brakes, the labor share will soon return to the levels we saw in most of the period from 1970 to the early 2000s.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that there was not an upward redistribution of income, but rather that it was mostly from low- and middle-wage earners to high wage earners. The latter group including doctors and dentists, Wall Street financial-types, CEOs and top executives, and folks in a position to benefit from patent and copyright rents. (This is the topic of Rigged: How the Rules of Globalization and the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

So we should definitely be worried about the upward redistribution of income, but it is not a story of a shift from wages to profits. But undoubtedly we can keep many eocnomists employed for some time trying to explain something that did not happen.

I see Noah Smith is struggling to explain “the mystery of labor’s falling share of GDP.” At the risk of jeopardizing good paying jobs for people with PhDs in economics, let me suggest that there is no mystery to explain.

Noah’s piece features a graph showing the labor share of GDP declining from a range of 64 to 65 percent in the 1960s and early 1970s to just over 60 percent in the most recent data. He then gives us several possible explanations for this drop. Let me give an alternative one, there was no drop or at least not much of one.

Suppose we look at the labor share of net domestic product. This is GDP after removing depreciation. This makes sense since deprecation is not something to be divided by labor and capital. It is the amount of output needed to replace worn out plant and equipment. The story since 1960 is below. (For those wanted to check the numbers, labor compensation comes from NIPA Table 1.10, Line 2; NDP from Table 1.7.5, Line 30.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

As we can see, there is no pattern of decline over the last five decades. In fact, the labor share of net domestic product is higher today than it was in the sixties. The labor share did fall sharply in the Great Recession, but this seems easy to attribute to the extraordinary weakness of the labor market. The share is now recovering and my bet is, that if the Fed can be prevented from slamming on the brakes, the labor share will soon return to the levels we saw in most of the period from 1970 to the early 2000s.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that there was not an upward redistribution of income, but rather that it was mostly from low- and middle-wage earners to high wage earners. The latter group including doctors and dentists, Wall Street financial-types, CEOs and top executives, and folks in a position to benefit from patent and copyright rents. (This is the topic of Rigged: How the Rules of Globalization and the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

So we should definitely be worried about the upward redistribution of income, but it is not a story of a shift from wages to profits. But undoubtedly we can keep many eocnomists employed for some time trying to explain something that did not happen.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Germany is running an annual trade surplus of more than 8.0 percent of its GDP (equivalent to $1.6 trillion in the U.S. economy). This huge trade surplus translates into large deficits for the rest of the world. This is the largest single cause of the problems facing Greece, Italy, Spain, and even France. All are seeing their growth and employment seriously constrained as a result of the large German trade surpluses.

In the good old days before the euro, Germany’s trade surplus would have led to a run-up in the value of its currency making its goods and services less competitive in the world economy, which would have diminished its surplus. However, now that Germany is in the euro, this mechanism for adjustment does not exist.

In the absence of an exchange rate adjustment, the mechanism for addressing the trade imbalance would be more rapid inflation and growth in Germany. The inflation would adjust relative prices and the growth would pull in more imports from Germany’s trading partners. For reasons that seem largely grounded in superstition, Germany refuses to embark on a more rapid growth path (it is running a budget surplus) and continues to maintain a very low inflation rate. (The two are directly linked, since more rapid growth would be the mechanism for increasing the inflation rate.

Instead of giving these basic facts to readers, the NYT ran a Reuters article that reported the dispute as a silly he said/she said. It told readers:

“The Trump administration has criticized Germany for its large trade surpluses with the United States, while Germany has said its companies make quality products that customers want to buy.”

The German response is of course meaningless. The fact that it has a trade surplus means that people want to buy its products at their current prices. If there was an adjustment process that made the German products, say 20 percent more expensive, many fewer people would want to buy them.

The piece also bizarrely asserts that the reform of the corporate income tax being considered by Republicans is “protectionist.” It is not obviously protectionist in a way the refunding of the value added tax on exports is protectionist, and it is certainly not as obviously protectionist as patent and copyright protection. In effect, what Reuters was telling readers is that it doesn’t like the tax proposal and they should not either.

Note: Typos corrected from an earlier post. Thanks to Robert Salzberg and MichiganMitch.

Germany is running an annual trade surplus of more than 8.0 percent of its GDP (equivalent to $1.6 trillion in the U.S. economy). This huge trade surplus translates into large deficits for the rest of the world. This is the largest single cause of the problems facing Greece, Italy, Spain, and even France. All are seeing their growth and employment seriously constrained as a result of the large German trade surpluses.

In the good old days before the euro, Germany’s trade surplus would have led to a run-up in the value of its currency making its goods and services less competitive in the world economy, which would have diminished its surplus. However, now that Germany is in the euro, this mechanism for adjustment does not exist.

In the absence of an exchange rate adjustment, the mechanism for addressing the trade imbalance would be more rapid inflation and growth in Germany. The inflation would adjust relative prices and the growth would pull in more imports from Germany’s trading partners. For reasons that seem largely grounded in superstition, Germany refuses to embark on a more rapid growth path (it is running a budget surplus) and continues to maintain a very low inflation rate. (The two are directly linked, since more rapid growth would be the mechanism for increasing the inflation rate.

Instead of giving these basic facts to readers, the NYT ran a Reuters article that reported the dispute as a silly he said/she said. It told readers:

“The Trump administration has criticized Germany for its large trade surpluses with the United States, while Germany has said its companies make quality products that customers want to buy.”

The German response is of course meaningless. The fact that it has a trade surplus means that people want to buy its products at their current prices. If there was an adjustment process that made the German products, say 20 percent more expensive, many fewer people would want to buy them.

The piece also bizarrely asserts that the reform of the corporate income tax being considered by Republicans is “protectionist.” It is not obviously protectionist in a way the refunding of the value added tax on exports is protectionist, and it is certainly not as obviously protectionist as patent and copyright protection. In effect, what Reuters was telling readers is that it doesn’t like the tax proposal and they should not either.

Note: Typos corrected from an earlier post. Thanks to Robert Salzberg and MichiganMitch.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

On the day of the March for Science the NYT ran a column by Chad Terhune, a senior correspondent for Kaiser Health News and California Healthline, telling readers that the economy was dependent on the health care sector to generate employment.

“The country has grown increasingly dependent on the health sector to power the economy, and it will be a tough habit to break. Thirty-five percent of the nation’s job growth has come from health care since the recession hit in late 2007, the single biggest sector for job creation.”

Okay, this is the story that we don’t have enough work to fully employ people. If we didn’t waste huge amounts of labor doing needless tasks in the health care sector, then millions of workers would be out on the street having nothing to do.

That sounds really bad. It’s also 180 degrees at odds with the conventional concern of economists, which is scarcity, an inadequate supply of labor. We see this story all the time in various forms. Just yesterday the Washington Post told readers about how the retirement of baby boomers was leading to a shortage of workers in construction and trucking.

More generally, the concern frequently expressed by the Washington Post, that an overly generous disability system is leading too many people to leave the labor force (actually we have the least generous system among rich countries), or concerns about budget deficits generally, are concerns about scarcity. In effect they mean that we don’t have enough workers to do what needs to be done. (For the record, the data seem to agree with the scarcity folks for the now, with productivity growth at historic lows for the last decade.)

Anyhow, it is striking that we have seemingly serious people who are 180 degrees at odds on this one. Either the planet as a whole is getting warmer or cooler, it can’t possible be both. Experts on climate science appear to be in agreement on this one. Unfortunately, in economic policy, we don’t need seem to know which way is up.

Perhaps even worse, no one gives a damn.

On the day of the March for Science the NYT ran a column by Chad Terhune, a senior correspondent for Kaiser Health News and California Healthline, telling readers that the economy was dependent on the health care sector to generate employment.

“The country has grown increasingly dependent on the health sector to power the economy, and it will be a tough habit to break. Thirty-five percent of the nation’s job growth has come from health care since the recession hit in late 2007, the single biggest sector for job creation.”

Okay, this is the story that we don’t have enough work to fully employ people. If we didn’t waste huge amounts of labor doing needless tasks in the health care sector, then millions of workers would be out on the street having nothing to do.

That sounds really bad. It’s also 180 degrees at odds with the conventional concern of economists, which is scarcity, an inadequate supply of labor. We see this story all the time in various forms. Just yesterday the Washington Post told readers about how the retirement of baby boomers was leading to a shortage of workers in construction and trucking.

More generally, the concern frequently expressed by the Washington Post, that an overly generous disability system is leading too many people to leave the labor force (actually we have the least generous system among rich countries), or concerns about budget deficits generally, are concerns about scarcity. In effect they mean that we don’t have enough workers to do what needs to be done. (For the record, the data seem to agree with the scarcity folks for the now, with productivity growth at historic lows for the last decade.)

Anyhow, it is striking that we have seemingly serious people who are 180 degrees at odds on this one. Either the planet as a whole is getting warmer or cooler, it can’t possible be both. Experts on climate science appear to be in agreement on this one. Unfortunately, in economic policy, we don’t need seem to know which way is up.

Perhaps even worse, no one gives a damn.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión