The New York Times ran a column by Michael Rips that inadvertently called attention to a major tax scam. Rips is unhappy because when artists and other creative workers donate their work to a museum or other charitable institution they can only deduct the value of the materials on their taxes. They cannot deduct the full market value of the work, nor any amount for their labor.

There is a simple reason why they can’t deduct the value of their labor from their taxes, they never paid taxes on their labor in the first place. Suppose a doctor or a lawyer could do work for school and then deduct the value of this work without ever paying taxes on it. This would be a very nice subsidy to the doctors or lawyers, but it doesn’t make sense as tax policy. Nor does it make sense to allow artists to deduct the market value of their work, if they had not already paid taxes on it.

But Rips does call attention to an important discrepancy in the tax code. Suppose a rich person buys a painting for $5 million and then donates it to a museum twenty years later when it has a market value of $50 million. The rich person is allowed to deduct the full market value of $50 million from their taxes, even though they only paid $5 million for the painting.

There is no obvious rationale for this sort of arrangement and it naturally encourages cheating. (Find me an appraiser who will say that my $40 million painting is worth $50 million and it gets me another $4 million off my taxes.) The more logical path would be to limit the person to deducting the original price of the work (perhaps with an inflation adjustment). The rich person could of course sell the painting, pay the capital gains tax, and then donate the proceeds to the museum, but then the museum doesn’t get the painting.

Anyhow, we know it’s hard to be rich, but there is no reason to have special tax breaks like the one Rips calls attention to.

The New York Times ran a column by Michael Rips that inadvertently called attention to a major tax scam. Rips is unhappy because when artists and other creative workers donate their work to a museum or other charitable institution they can only deduct the value of the materials on their taxes. They cannot deduct the full market value of the work, nor any amount for their labor.

There is a simple reason why they can’t deduct the value of their labor from their taxes, they never paid taxes on their labor in the first place. Suppose a doctor or a lawyer could do work for school and then deduct the value of this work without ever paying taxes on it. This would be a very nice subsidy to the doctors or lawyers, but it doesn’t make sense as tax policy. Nor does it make sense to allow artists to deduct the market value of their work, if they had not already paid taxes on it.

But Rips does call attention to an important discrepancy in the tax code. Suppose a rich person buys a painting for $5 million and then donates it to a museum twenty years later when it has a market value of $50 million. The rich person is allowed to deduct the full market value of $50 million from their taxes, even though they only paid $5 million for the painting.

There is no obvious rationale for this sort of arrangement and it naturally encourages cheating. (Find me an appraiser who will say that my $40 million painting is worth $50 million and it gets me another $4 million off my taxes.) The more logical path would be to limit the person to deducting the original price of the work (perhaps with an inflation adjustment). The rich person could of course sell the painting, pay the capital gains tax, and then donate the proceeds to the museum, but then the museum doesn’t get the painting.

Anyhow, we know it’s hard to be rich, but there is no reason to have special tax breaks like the one Rips calls attention to.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an interesting piece on how employers in traditionally male-dominated industries, like construction and trucking, are increasingly looking to hire women. While opening up these relatively high-paying sectors to women is certainly good news, the argument in the article really does not make sense.

The piece asserts that employers are having difficulty finding qualified workers, in large part because of the retirement of large numbers of baby boomers. If employers are really having trouble finding workers then we should see rapidly rising wages in these sectors. We don’t.

The piece focuses on iron workers, a skilled construction trade. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average real hourly wage among specialty trade contractors, the category that includes iron workers, has risen by less than 3.0 percent since its peak in 2002.

Average Hourly Earnings: Specialty Trade Contractors

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That is annual rate of increase of roughly 0.2 percent. That is not what we would expect in an occupation facing a labor shortage. (Earnings are expressed in 1982–84 dollars, multiply by roughly 2.5 to get 2017 dollars.) It’s great that doors are being opened to women, but there is not evidence of a labor shortage in this sector.

The piece also included an interesting discussion of a looming worker shortage in the trucking industry:

“The American Trucking Associations, meanwhile, declared in a recent report that the industry needs to add almost 1 million new drivers by 2024 to replace retired drivers and keep up with demand.”

In recent months there have been endless news stories about how self-driving vehicles were going to lead to mass unemployment in the trucking industry. This seems like more evidence of the which way is up problem in economics; we will either have a massive shortage of workers in the trucking industry or mass unemployment. Whichever, it clearly is a serious problem.

The Washington Post had an interesting piece on how employers in traditionally male-dominated industries, like construction and trucking, are increasingly looking to hire women. While opening up these relatively high-paying sectors to women is certainly good news, the argument in the article really does not make sense.

The piece asserts that employers are having difficulty finding qualified workers, in large part because of the retirement of large numbers of baby boomers. If employers are really having trouble finding workers then we should see rapidly rising wages in these sectors. We don’t.

The piece focuses on iron workers, a skilled construction trade. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average real hourly wage among specialty trade contractors, the category that includes iron workers, has risen by less than 3.0 percent since its peak in 2002.

Average Hourly Earnings: Specialty Trade Contractors

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That is annual rate of increase of roughly 0.2 percent. That is not what we would expect in an occupation facing a labor shortage. (Earnings are expressed in 1982–84 dollars, multiply by roughly 2.5 to get 2017 dollars.) It’s great that doors are being opened to women, but there is not evidence of a labor shortage in this sector.

The piece also included an interesting discussion of a looming worker shortage in the trucking industry:

“The American Trucking Associations, meanwhile, declared in a recent report that the industry needs to add almost 1 million new drivers by 2024 to replace retired drivers and keep up with demand.”

In recent months there have been endless news stories about how self-driving vehicles were going to lead to mass unemployment in the trucking industry. This seems like more evidence of the which way is up problem in economics; we will either have a massive shortage of workers in the trucking industry or mass unemployment. Whichever, it clearly is a serious problem.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the gist of Anne Applebaum’s Washington Post column today. In a discussion of the upcoming election in the United Kingdom, she refers to the political stances of the Labor Party, the Conservative Party, and the Scottish National Party:

“Curiously, the three parties do have one thing in common: They all claim to be fighting for “the people” against an unnamed and ill-defined “elite.” They all offer their followers a new sort of identity: Voters can now define themselves as “Brexiteers,” as class warriors or as Scots, opposing themselves against enemies in (take your pick) journalism/academia/the judiciary/London/abroad/financial markets/England. If you were wondering whether “populism” was nothing more than a political strategy, easily tailored to elect any party of any ideology, you have your answer. Left-wing radicals, right-wing radicals and Scottish radicals all share a style, if not an agenda.”

So there you have it. We can’t actually have a politics directed against all the money going to the rich because, everyone says they are against the elite. I guess the only thing left to do is cut programs like Social Security and disability and have the Federal Reserve Board raise interest rates to keep people from having jobs. Otherwise, you could be a populist.

That’s the gist of Anne Applebaum’s Washington Post column today. In a discussion of the upcoming election in the United Kingdom, she refers to the political stances of the Labor Party, the Conservative Party, and the Scottish National Party:

“Curiously, the three parties do have one thing in common: They all claim to be fighting for “the people” against an unnamed and ill-defined “elite.” They all offer their followers a new sort of identity: Voters can now define themselves as “Brexiteers,” as class warriors or as Scots, opposing themselves against enemies in (take your pick) journalism/academia/the judiciary/London/abroad/financial markets/England. If you were wondering whether “populism” was nothing more than a political strategy, easily tailored to elect any party of any ideology, you have your answer. Left-wing radicals, right-wing radicals and Scottish radicals all share a style, if not an agenda.”

So there you have it. We can’t actually have a politics directed against all the money going to the rich because, everyone says they are against the elite. I guess the only thing left to do is cut programs like Social Security and disability and have the Federal Reserve Board raise interest rates to keep people from having jobs. Otherwise, you could be a populist.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a Reuters article which reported on the German government’s response to I.M.F. complaints about its trade surplus. The essence of the response was the German government lacked the competence to reduce its trade surplus, which is currently more than 8.0 percent of GDP ($1.6 trillion in the U.S.). The German trade surplus is of course a deficit for other countries, which are seeing a loss of output and employment as a result.

Because Germany is in the euro, the most important tool for addressing an excessive trade surplus, a rise in the value of the currency, is not available as an option. A higher valued euro would hurt the competitive position of other countries in the euro, like Greece, Portugal, and Spain, that are struggling with slow growth and high unemployment. Of course, a change in the value of the euro does not affect Germany’s position at all relative to its main trading partners within the euro.

The mechanism for an adjustment in this case would be for Germany to increase demand and to try to raise its domestic inflation rate. The best way to increase its budget deficit. Unfortunately, instead of running large budget deficits, Germany is running a budget surplus of 0.6 percent of GDP ($115 billion annually in the United States).

If Germany continues to run large trade surplus, then heavily indebted countries like Greece will inevitably need further debt relief. In effect, this means that Germany will have given away its exports in prior years. If Germany were prepared to run more expansionary fiscal policy and allow its inflation rate to rise somewhat then it could have more balanced trade, meaning that it would be getting something in exchange for its exports.

However, Germany’s political leaders would apparently prefer to give things away to its trading partners in order to feel virtuous about balanced budgets and low inflation. The price for this “virtue” in much of the rest of the euro zone is slow growth, stagnating wages, and mass unemployment.

The NYT ran a Reuters article which reported on the German government’s response to I.M.F. complaints about its trade surplus. The essence of the response was the German government lacked the competence to reduce its trade surplus, which is currently more than 8.0 percent of GDP ($1.6 trillion in the U.S.). The German trade surplus is of course a deficit for other countries, which are seeing a loss of output and employment as a result.

Because Germany is in the euro, the most important tool for addressing an excessive trade surplus, a rise in the value of the currency, is not available as an option. A higher valued euro would hurt the competitive position of other countries in the euro, like Greece, Portugal, and Spain, that are struggling with slow growth and high unemployment. Of course, a change in the value of the euro does not affect Germany’s position at all relative to its main trading partners within the euro.

The mechanism for an adjustment in this case would be for Germany to increase demand and to try to raise its domestic inflation rate. The best way to increase its budget deficit. Unfortunately, instead of running large budget deficits, Germany is running a budget surplus of 0.6 percent of GDP ($115 billion annually in the United States).

If Germany continues to run large trade surplus, then heavily indebted countries like Greece will inevitably need further debt relief. In effect, this means that Germany will have given away its exports in prior years. If Germany were prepared to run more expansionary fiscal policy and allow its inflation rate to rise somewhat then it could have more balanced trade, meaning that it would be getting something in exchange for its exports.

However, Germany’s political leaders would apparently prefer to give things away to its trading partners in order to feel virtuous about balanced budgets and low inflation. The price for this “virtue” in much of the rest of the euro zone is slow growth, stagnating wages, and mass unemployment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A New York Times article on the newest growth forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.) described the I.M.F. as “the most ardent defender of traditional free-trade policies.” This is not accurate.

The I.M.F. has been fine with ever stronger and longer patent and copyright protections. These government imposed monopolies raise the price of protected items by factors or ten or even a hundred above the free market price, making them equivalent to tariffs of hundreds or thousands of percent. These protections both have negative economic impacts, as would be predicted from any tariff of this size, and also are major factors in the upward redistribution of income that we have seen in most countries in recent decades.

The impact of these monopolies is most dramatic in prescription drugs. In the United States, we will spend more than $440 billion this year on drugs that would likely cost less than $80 billion in a free market. This gap of $360 billion is almost 2.0 percent of GDP. It is roughly five times what we spend on food stamps each year. It is more than 20 percent of the wage income of the bottom half of the workforce.

In addition, the huge gap between the protected price and the free market price leads to the sort of corruption that economists predict from tariff protection. It is standard practice for drug companies to promote their drugs for uses where they may not be appropriate. They also often conceal evidence that their drugs are not as safe or effective as claimed.

The cumulative cost of these protections in other areas is likely comparable. Anyone who supports these government granted monopolies cannot accurately be described as a proponent of free trade.

A New York Times article on the newest growth forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.) described the I.M.F. as “the most ardent defender of traditional free-trade policies.” This is not accurate.

The I.M.F. has been fine with ever stronger and longer patent and copyright protections. These government imposed monopolies raise the price of protected items by factors or ten or even a hundred above the free market price, making them equivalent to tariffs of hundreds or thousands of percent. These protections both have negative economic impacts, as would be predicted from any tariff of this size, and also are major factors in the upward redistribution of income that we have seen in most countries in recent decades.

The impact of these monopolies is most dramatic in prescription drugs. In the United States, we will spend more than $440 billion this year on drugs that would likely cost less than $80 billion in a free market. This gap of $360 billion is almost 2.0 percent of GDP. It is roughly five times what we spend on food stamps each year. It is more than 20 percent of the wage income of the bottom half of the workforce.

In addition, the huge gap between the protected price and the free market price leads to the sort of corruption that economists predict from tariff protection. It is standard practice for drug companies to promote their drugs for uses where they may not be appropriate. They also often conceal evidence that their drugs are not as safe or effective as claimed.

The cumulative cost of these protections in other areas is likely comparable. Anyone who supports these government granted monopolies cannot accurately be described as a proponent of free trade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In fact, it wasn’t even $800 billion, but the Washington Post has never been very good with numbers. The issue came up in a column by Paul Kane telling Republicans that they don’t have to just focus on really big items. The second paragraph refers to the Democrat’s big agenda after President Obama took office:

“Everyone knows the big agenda they pursued — an $800 billion economic stimulus, a sweeping health-care law and an overhaul of Wall Street regulations.”

The stimulus was actually closer to $700 billion since around $70 billion of the “stimulus” involved extensions of tax breaks that would have been extended in almost any circumstances. This was actually a very small response to the collapse of a housing bubble that cost the economy close to $1,200 billion dollars in annual demand (6–7 percent of GDP).

The Obama administration tried to counteract this huge loss of demand with a stimulus that was roughly 2 percent of GDP for two years and then trailed off to almost nothing. This was way too small, as some of us argued at the time.

The country has paid an enormous price for this inadequate stimulus with the economy now more than 10 percent below the level that had been projected by the Congressional Budget Office for 2017 before the crash. This gap is close to $2 trillion a year or $6,000 for every person in the country. This is known as the “austerity tax,” the cost the country pays because folks like Peter Peterson and the Washington Post (in both the opinion and news sections) endlessly yelled about debt and deficits at a time when they clearly were not a problem.

It is also worth noting that the overhaul of Wall Street was not especially ambitious. It left the big banks largely intact and did not involve prosecuting any Wall Street executives for crimes they may have committed during the bubble years, such as knowingly passing on fraudulent mortgages in mortgage backed securities.

Note:

Typos corrected, thanks for Robert Salzberg and Boris Soroker.

In fact, it wasn’t even $800 billion, but the Washington Post has never been very good with numbers. The issue came up in a column by Paul Kane telling Republicans that they don’t have to just focus on really big items. The second paragraph refers to the Democrat’s big agenda after President Obama took office:

“Everyone knows the big agenda they pursued — an $800 billion economic stimulus, a sweeping health-care law and an overhaul of Wall Street regulations.”

The stimulus was actually closer to $700 billion since around $70 billion of the “stimulus” involved extensions of tax breaks that would have been extended in almost any circumstances. This was actually a very small response to the collapse of a housing bubble that cost the economy close to $1,200 billion dollars in annual demand (6–7 percent of GDP).

The Obama administration tried to counteract this huge loss of demand with a stimulus that was roughly 2 percent of GDP for two years and then trailed off to almost nothing. This was way too small, as some of us argued at the time.

The country has paid an enormous price for this inadequate stimulus with the economy now more than 10 percent below the level that had been projected by the Congressional Budget Office for 2017 before the crash. This gap is close to $2 trillion a year or $6,000 for every person in the country. This is known as the “austerity tax,” the cost the country pays because folks like Peter Peterson and the Washington Post (in both the opinion and news sections) endlessly yelled about debt and deficits at a time when they clearly were not a problem.

It is also worth noting that the overhaul of Wall Street was not especially ambitious. It left the big banks largely intact and did not involve prosecuting any Wall Street executives for crimes they may have committed during the bubble years, such as knowingly passing on fraudulent mortgages in mortgage backed securities.

Note:

Typos corrected, thanks for Robert Salzberg and Boris Soroker.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post economics reporter Max Ehrenfreund featured a piece highlighting former Donald Trump adviser Steven Moore’s views of Trump’s recent shifts on economic policy. In particular, Moore took issue with Trump’s desire to see the value of the dollar fall. He argued that the dollar rose with strong economies under President Reagan and Clinton, while it was weak under Nixon, Ford, and Carter.

Actually, it is not especially accurate to claim the dollar rose under President Reagan. Using the Federal Reserve Board’s broad real index, it was trivially higher in January of 1989 than it was when Reagan took office in January of 1981 (91.3 in 1989 compared to 89.7 in 1981). The comparison goes the other way if we use December of 1988 (89.8) and December of 1989 (90.6), the last full month of Carter and Reagan’s terms.

As a practical matter, the run-up in the dollar in the first part of the Reagan administration led to a large trade deficit, causing serious hardship in manufacturing sectors. In response, Reagan’s Treasury secretary negotiated an orderly decline in the value of the dollar to bring down the deficit, which it did.

Also, if we are using the value of the dollar as a measure of the strength of the economy under different presidents, we find that it was virtually unchanged through President George H.W. Bush’s presidency and Clinton’s first term. The former was a period of weak growth, while the latter was a period of strong growth.

Washington Post economics reporter Max Ehrenfreund featured a piece highlighting former Donald Trump adviser Steven Moore’s views of Trump’s recent shifts on economic policy. In particular, Moore took issue with Trump’s desire to see the value of the dollar fall. He argued that the dollar rose with strong economies under President Reagan and Clinton, while it was weak under Nixon, Ford, and Carter.

Actually, it is not especially accurate to claim the dollar rose under President Reagan. Using the Federal Reserve Board’s broad real index, it was trivially higher in January of 1989 than it was when Reagan took office in January of 1981 (91.3 in 1989 compared to 89.7 in 1981). The comparison goes the other way if we use December of 1988 (89.8) and December of 1989 (90.6), the last full month of Carter and Reagan’s terms.

As a practical matter, the run-up in the dollar in the first part of the Reagan administration led to a large trade deficit, causing serious hardship in manufacturing sectors. In response, Reagan’s Treasury secretary negotiated an orderly decline in the value of the dollar to bring down the deficit, which it did.

Also, if we are using the value of the dollar as a measure of the strength of the economy under different presidents, we find that it was virtually unchanged through President George H.W. Bush’s presidency and Clinton’s first term. The former was a period of weak growth, while the latter was a period of strong growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

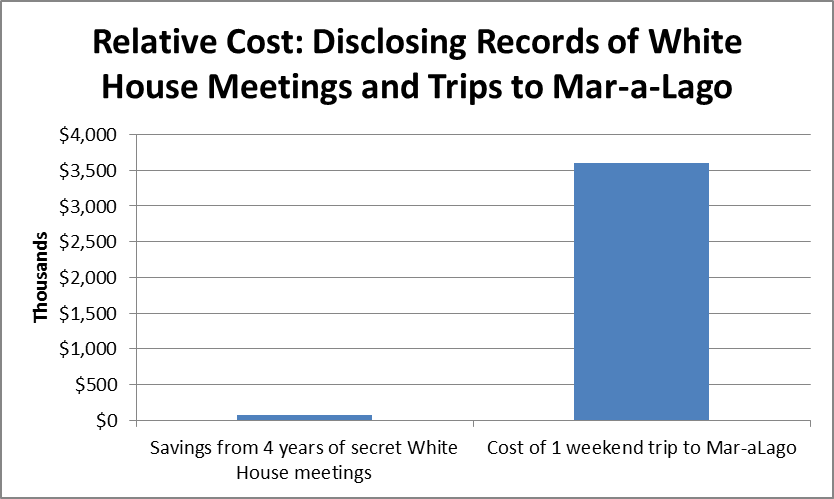

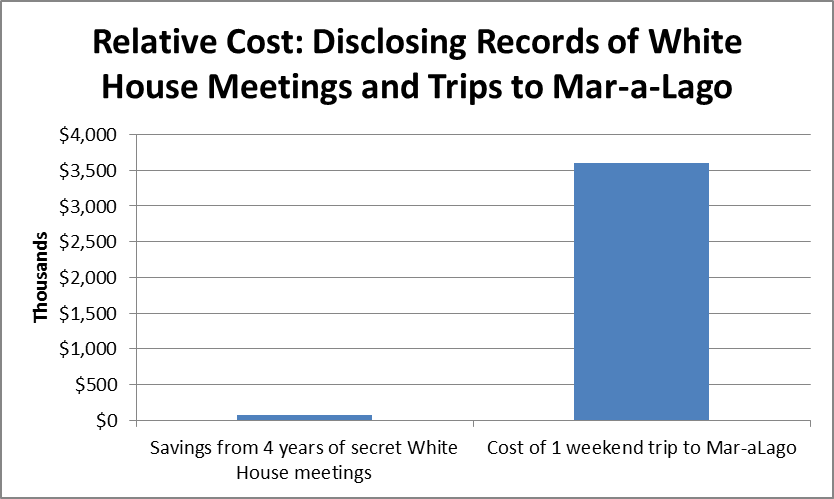

The Trump administration announced that would end the Obama administration’s practice of revealing the list of people who visit the White House. This list was useful in letting the public know who President Trump was making deals with.

The administration claimed this move was taken as a security measure and also to save the country $70,000 over the next four years. Since the government is projected to spend roughly $16 trillion over the next four years, the savings will be equal to 0.00000004 percent of projected spending. Alternatively, it will save each person in the country 0.007 cents annually over the next four years.

Another comparison that might be useful is that it costs taxpayers more than $3 million in additional security costs every time that President Trump goes to Mar-a-Lago for the weekend. This means that Trump is saving us an amount equal to 2 percent of the cost of one of his weekend trips by keeping the records of his meetings secret.

Source: See text.

The Trump administration announced that would end the Obama administration’s practice of revealing the list of people who visit the White House. This list was useful in letting the public know who President Trump was making deals with.

The administration claimed this move was taken as a security measure and also to save the country $70,000 over the next four years. Since the government is projected to spend roughly $16 trillion over the next four years, the savings will be equal to 0.00000004 percent of projected spending. Alternatively, it will save each person in the country 0.007 cents annually over the next four years.

Another comparison that might be useful is that it costs taxpayers more than $3 million in additional security costs every time that President Trump goes to Mar-a-Lago for the weekend. This means that Trump is saving us an amount equal to 2 percent of the cost of one of his weekend trips by keeping the records of his meetings secret.

Source: See text.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I know Donald Trump is lots of fun and everything, but people should be paying at least a little attention to inflation, or the lack thereof. Remember, last time we tuned in the Federal Reserve Board was embarked on a process of tightening through a sequence of interest rates hikes. The concern expressed by proponents of higher rates was that the economy was too strong and that inflation would soon be rising above its 2.0 percent target. (Actually, the target is supposed to be an average, which means at the peak of a recovery the inflation rate should be somewhat higher than 2.0 percent.)

The March data seems to undermine this concern. While monthly data are erratic, it was striking because both the overall and core rate were negative in the month. The core CPI dropped by 0.1 percent in March, its first decline in more than seven years.

Furthermore, even the modest inflation shown by the core index is largely due to rents. While higher rents do affect people’s cost of living, the Fed is not going to slow rental inflation by raising interest rates. In fact, by slowing construction, the near-term impact of higher interest rates could be to increase inflation in rents.

Over the last year, a core CPI that excludes rent has risen by just 1.0 percent.

Year over Year Change in Core CPI, Excluding Housing

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

I know Donald Trump is lots of fun and everything, but people should be paying at least a little attention to inflation, or the lack thereof. Remember, last time we tuned in the Federal Reserve Board was embarked on a process of tightening through a sequence of interest rates hikes. The concern expressed by proponents of higher rates was that the economy was too strong and that inflation would soon be rising above its 2.0 percent target. (Actually, the target is supposed to be an average, which means at the peak of a recovery the inflation rate should be somewhat higher than 2.0 percent.)

The March data seems to undermine this concern. While monthly data are erratic, it was striking because both the overall and core rate were negative in the month. The core CPI dropped by 0.1 percent in March, its first decline in more than seven years.

Furthermore, even the modest inflation shown by the core index is largely due to rents. While higher rents do affect people’s cost of living, the Fed is not going to slow rental inflation by raising interest rates. In fact, by slowing construction, the near-term impact of higher interest rates could be to increase inflation in rents.

Over the last year, a core CPI that excludes rent has risen by just 1.0 percent.

Year over Year Change in Core CPI, Excluding Housing

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión