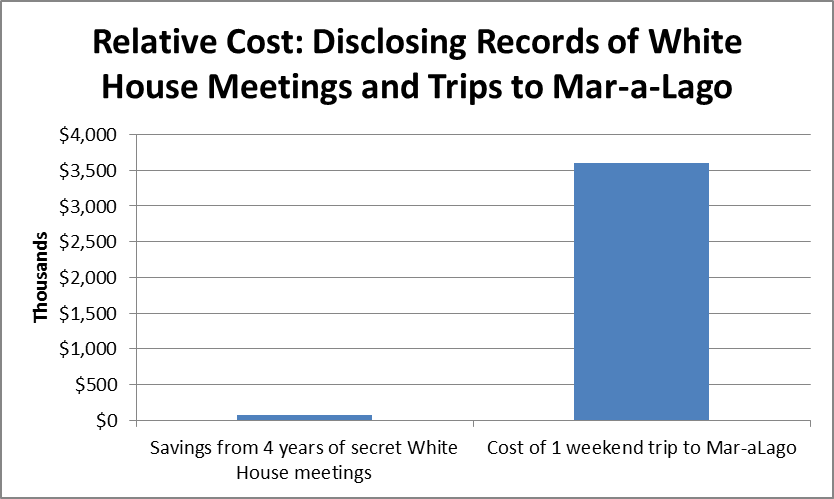

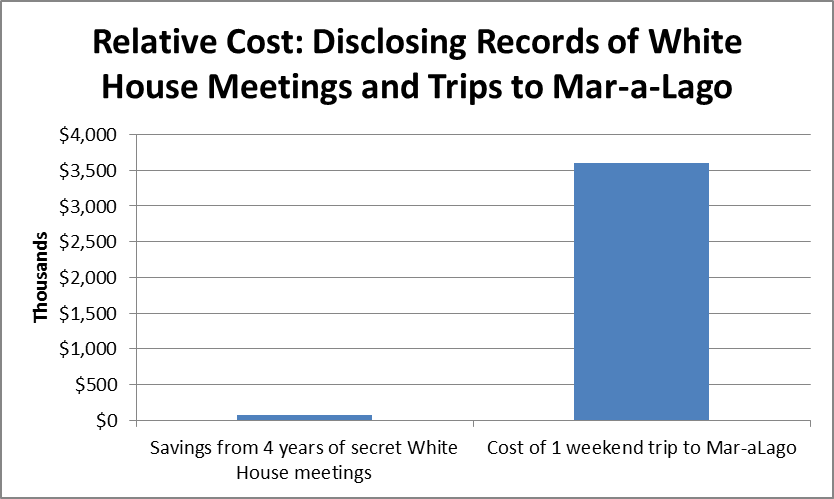

The Trump administration announced that would end the Obama administration’s practice of revealing the list of people who visit the White House. This list was useful in letting the public know who President Trump was making deals with.

The administration claimed this move was taken as a security measure and also to save the country $70,000 over the next four years. Since the government is projected to spend roughly $16 trillion over the next four years, the savings will be equal to 0.00000004 percent of projected spending. Alternatively, it will save each person in the country 0.007 cents annually over the next four years.

Another comparison that might be useful is that it costs taxpayers more than $3 million in additional security costs every time that President Trump goes to Mar-a-Lago for the weekend. This means that Trump is saving us an amount equal to 2 percent of the cost of one of his weekend trips by keeping the records of his meetings secret.

Source: See text.

The Trump administration announced that would end the Obama administration’s practice of revealing the list of people who visit the White House. This list was useful in letting the public know who President Trump was making deals with.

The administration claimed this move was taken as a security measure and also to save the country $70,000 over the next four years. Since the government is projected to spend roughly $16 trillion over the next four years, the savings will be equal to 0.00000004 percent of projected spending. Alternatively, it will save each person in the country 0.007 cents annually over the next four years.

Another comparison that might be useful is that it costs taxpayers more than $3 million in additional security costs every time that President Trump goes to Mar-a-Lago for the weekend. This means that Trump is saving us an amount equal to 2 percent of the cost of one of his weekend trips by keeping the records of his meetings secret.

Source: See text.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I know Donald Trump is lots of fun and everything, but people should be paying at least a little attention to inflation, or the lack thereof. Remember, last time we tuned in the Federal Reserve Board was embarked on a process of tightening through a sequence of interest rates hikes. The concern expressed by proponents of higher rates was that the economy was too strong and that inflation would soon be rising above its 2.0 percent target. (Actually, the target is supposed to be an average, which means at the peak of a recovery the inflation rate should be somewhat higher than 2.0 percent.)

The March data seems to undermine this concern. While monthly data are erratic, it was striking because both the overall and core rate were negative in the month. The core CPI dropped by 0.1 percent in March, its first decline in more than seven years.

Furthermore, even the modest inflation shown by the core index is largely due to rents. While higher rents do affect people’s cost of living, the Fed is not going to slow rental inflation by raising interest rates. In fact, by slowing construction, the near-term impact of higher interest rates could be to increase inflation in rents.

Over the last year, a core CPI that excludes rent has risen by just 1.0 percent.

Year over Year Change in Core CPI, Excluding Housing

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

I know Donald Trump is lots of fun and everything, but people should be paying at least a little attention to inflation, or the lack thereof. Remember, last time we tuned in the Federal Reserve Board was embarked on a process of tightening through a sequence of interest rates hikes. The concern expressed by proponents of higher rates was that the economy was too strong and that inflation would soon be rising above its 2.0 percent target. (Actually, the target is supposed to be an average, which means at the peak of a recovery the inflation rate should be somewhat higher than 2.0 percent.)

The March data seems to undermine this concern. While monthly data are erratic, it was striking because both the overall and core rate were negative in the month. The core CPI dropped by 0.1 percent in March, its first decline in more than seven years.

Furthermore, even the modest inflation shown by the core index is largely due to rents. While higher rents do affect people’s cost of living, the Fed is not going to slow rental inflation by raising interest rates. In fact, by slowing construction, the near-term impact of higher interest rates could be to increase inflation in rents.

Over the last year, a core CPI that excludes rent has risen by just 1.0 percent.

Year over Year Change in Core CPI, Excluding Housing

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Federal Reserve Board has more direct control over the economy than any other institution in the country. When it decides to raise interest rates to slow the economy, it can ensure that millions of workers don’t get jobs and prevent tens of millions more from getting the bargaining power they need to gain wage increases. For this reason, it is very important who is making the calls on interest rates and who they are listening to.

Robert Rubin, who served as Treasury secretary in the Clinton administration, weighed in today in the NYT to argue for the status quo. There are a few important background points on Rubin that are worth mentioning before getting into the substance.

First. Robert Rubin was a main architect of the high dollar policy that led to the explosion of the trade deficit in the last decade. This led to the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs and decimating communities across the Midwest. Second, Rubin was a major advocate of financial deregulation during his years in the Clinton administration. Finally, Rubin was a direct beneficiary of deregulation, since he left the administration to take a top job at Citigroup. He made over $100 million in this position before he resigned in the financial crisis when bad loans had essentially put Citigroup into bankruptcy. (It was saved by government bailouts.)

Rubin touts the current apolitical nature of the Fed. He warns about:

“Efforts to denigrate the integrity of the Fed’s work, and to inject groundless opinion, politics and ideology, must be rejected by the board — and that means governors and other members of the Federal Open Market Committee must be willing to withstand aggressive attacks.”

It is important to recognize that the Fed is currently dominated by people with close ties to the financial industry. The Fed Open Market Committee (FOMC) which determines interest rate policy has 19 members. While 7 are governors appointed by the president and approved by Congress (only 4 of the governor seats are currently filled), 12 are presidents of the district banks. These bank presidents are appointed through a process dominated by the banks in the district. (Only 5 of the 12 presidents have a vote at any one time, but all 12 participate in discussions.)

It seems bizarre to describe this process as apolitical or imply there is great integrity here. Rubin’s claim is particularly ironic in light of the fact that one of the bank presidents was just forced to resign after admitting to leaking confidential information on interest rate policy to a financial analyst.

There is good reason for the public to be unhappy about the Fed’s excessive concern over inflation over the last four decades and inadequate attention to unemployment. This arguably reflects the interests of the financial industry, which often stands to lose from higher inflation and have little interest in the level of employment. It is understandable that someone who has made his fortune in the financial industry would want to protect the status quo with the Fed, but there is little reason for the rest of us to take him seriously.

The Federal Reserve Board has more direct control over the economy than any other institution in the country. When it decides to raise interest rates to slow the economy, it can ensure that millions of workers don’t get jobs and prevent tens of millions more from getting the bargaining power they need to gain wage increases. For this reason, it is very important who is making the calls on interest rates and who they are listening to.

Robert Rubin, who served as Treasury secretary in the Clinton administration, weighed in today in the NYT to argue for the status quo. There are a few important background points on Rubin that are worth mentioning before getting into the substance.

First. Robert Rubin was a main architect of the high dollar policy that led to the explosion of the trade deficit in the last decade. This led to the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs and decimating communities across the Midwest. Second, Rubin was a major advocate of financial deregulation during his years in the Clinton administration. Finally, Rubin was a direct beneficiary of deregulation, since he left the administration to take a top job at Citigroup. He made over $100 million in this position before he resigned in the financial crisis when bad loans had essentially put Citigroup into bankruptcy. (It was saved by government bailouts.)

Rubin touts the current apolitical nature of the Fed. He warns about:

“Efforts to denigrate the integrity of the Fed’s work, and to inject groundless opinion, politics and ideology, must be rejected by the board — and that means governors and other members of the Federal Open Market Committee must be willing to withstand aggressive attacks.”

It is important to recognize that the Fed is currently dominated by people with close ties to the financial industry. The Fed Open Market Committee (FOMC) which determines interest rate policy has 19 members. While 7 are governors appointed by the president and approved by Congress (only 4 of the governor seats are currently filled), 12 are presidents of the district banks. These bank presidents are appointed through a process dominated by the banks in the district. (Only 5 of the 12 presidents have a vote at any one time, but all 12 participate in discussions.)

It seems bizarre to describe this process as apolitical or imply there is great integrity here. Rubin’s claim is particularly ironic in light of the fact that one of the bank presidents was just forced to resign after admitting to leaking confidential information on interest rate policy to a financial analyst.

There is good reason for the public to be unhappy about the Fed’s excessive concern over inflation over the last four decades and inadequate attention to unemployment. This arguably reflects the interests of the financial industry, which often stands to lose from higher inflation and have little interest in the level of employment. It is understandable that someone who has made his fortune in the financial industry would want to protect the status quo with the Fed, but there is little reason for the rest of us to take him seriously.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post and other major news outlets are strong supporters of the trade policy pursued by administrations of both political parties. They routinely allow their position on this issue to spill over into their news reporting, touting the policy as “free trade.” We got yet another example of this in the Washington Post today.

Of course the policy is very far from free trade. We have largely left in place the protectionist barriers that keep doctors and dentists from other countries from competing with our own doctors. (Doctors have to complete a U.S. residency program before they can practice in the United States and dentists must graduate from a U.S. dental school. The lone exception is for Canadian doctors and dentists, although even here we have left unnecessary barriers in place.)

As a result of this protectionism, average pay for doctors is over $250,000 a year and more than $200,000 a year for dentists, putting the vast majority of both groups in the top 2.0 percent of wage earners. Their pay is roughly twice the average received by their counterparts in other wealthy countries, adding close to $100 billion a year ($700 per family per year) to our medical bill.

While trade negotiators may feel this protectionism is justified, since these professionals lack the skills to compete in the global economy, it is nonetheless protectionism, not free trade.

We also have actively been pushing for longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. While these protections, like all forms of protectionism, serve a purpose, they are 180 degrees at odds with free trade. And, they are very costly. Patent protection in prescription drugs will lead to us pay more than $440 billion this year for drugs that would likely sell for less than $80 billion in a free market. The difference of $360 billion comes to almost $3,000 a year for every family in the country.

It is also worth noting patent protection results in exactly the sort of corruption that would be expected from a huge government imposed tariff. (When patents raise the price of a drug by a factor of 100 or more, as is often the case, it is equivalent to a tariff of 10,000 percent.) The result is that pharmaceutical companies often make payoffs to doctors to promote their drugs or conceal evidence that their drugs are less effective than claimed or even harmful.

The Washington Post and other major news outlets are strong supporters of the trade policy pursued by administrations of both political parties. They routinely allow their position on this issue to spill over into their news reporting, touting the policy as “free trade.” We got yet another example of this in the Washington Post today.

Of course the policy is very far from free trade. We have largely left in place the protectionist barriers that keep doctors and dentists from other countries from competing with our own doctors. (Doctors have to complete a U.S. residency program before they can practice in the United States and dentists must graduate from a U.S. dental school. The lone exception is for Canadian doctors and dentists, although even here we have left unnecessary barriers in place.)

As a result of this protectionism, average pay for doctors is over $250,000 a year and more than $200,000 a year for dentists, putting the vast majority of both groups in the top 2.0 percent of wage earners. Their pay is roughly twice the average received by their counterparts in other wealthy countries, adding close to $100 billion a year ($700 per family per year) to our medical bill.

While trade negotiators may feel this protectionism is justified, since these professionals lack the skills to compete in the global economy, it is nonetheless protectionism, not free trade.

We also have actively been pushing for longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. While these protections, like all forms of protectionism, serve a purpose, they are 180 degrees at odds with free trade. And, they are very costly. Patent protection in prescription drugs will lead to us pay more than $440 billion this year for drugs that would likely sell for less than $80 billion in a free market. The difference of $360 billion comes to almost $3,000 a year for every family in the country.

It is also worth noting patent protection results in exactly the sort of corruption that would be expected from a huge government imposed tariff. (When patents raise the price of a drug by a factor of 100 or more, as is often the case, it is equivalent to a tariff of 10,000 percent.) The result is that pharmaceutical companies often make payoffs to doctors to promote their drugs or conceal evidence that their drugs are less effective than claimed or even harmful.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Republicans have been working hard to find a way to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that doesn’t leave most of their members of Congress unemployed. The basic problem is that their campaign against the ACA for the last seven years was a complete lie. They claimed that people were paying too much money for policies that were inadequate, leading people to believe that they had a way to provide better coverage for less money. They don’t.

Unfortunately, NPR might have led listeners to believe otherwise in an interview with Mike Johnson, a Republican representative from Louisiana. Johnson explained that they would get premiums down by allowing insurers to exclude people with health conditions from their pool. This is more or less the situation we had before the ACA.

Most people are healthy and have few medical bills. Insurers are very happy to insure these people, since they essentially are just sending the companies money. The problem has always been the the roughly 10 percent of the population with substantial medical bills. Insurers don’t want to insure these people, since their health care costs serious money. Of course, these are the people who most need insurance.

Johnson acknowledged that these people will face higher premiums under his plan, but then said that they had set aside $15 billion in their bill for subsidies for these people. Was this information helpful to you?

It didn’t do much for me, since he didn’t even tell us the time frame for this $15 billion. Budget numbers are often expressed over ten year periods reflecting the Congressional Budget Office’s 10-year planning horizon. Was this a ten year number or a one year number? My guess is the former, but I really don’t know. Hey, so we’re off by a factor of ten, what’s the big deal?

But it gets worse. What’s the need here? Anyone know how far $15 billion will go over either a one year or ten year horizon?

To fill in the perspective a serious reporter would have given, the average annual health care costs for the 10 percent most costly patients is more than $50,000 a year. We’re talking about 32 million people, so that comes to more than $1.5 trillion a year.

Many of these people are on Medicare, and some are covered by employer provided insurance, so many will not end up in these high risk pools and need subsidies. But, let’s say that one third of them do end up in these pools. That means the cost would be $500 billion a year for these folks’ health care. Mr. Johnson is proposing a subsidy of between $1.5 billion and $15 billion to help these people cover their insurance.

Got the picture now?

The Republicans have been working hard to find a way to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that doesn’t leave most of their members of Congress unemployed. The basic problem is that their campaign against the ACA for the last seven years was a complete lie. They claimed that people were paying too much money for policies that were inadequate, leading people to believe that they had a way to provide better coverage for less money. They don’t.

Unfortunately, NPR might have led listeners to believe otherwise in an interview with Mike Johnson, a Republican representative from Louisiana. Johnson explained that they would get premiums down by allowing insurers to exclude people with health conditions from their pool. This is more or less the situation we had before the ACA.

Most people are healthy and have few medical bills. Insurers are very happy to insure these people, since they essentially are just sending the companies money. The problem has always been the the roughly 10 percent of the population with substantial medical bills. Insurers don’t want to insure these people, since their health care costs serious money. Of course, these are the people who most need insurance.

Johnson acknowledged that these people will face higher premiums under his plan, but then said that they had set aside $15 billion in their bill for subsidies for these people. Was this information helpful to you?

It didn’t do much for me, since he didn’t even tell us the time frame for this $15 billion. Budget numbers are often expressed over ten year periods reflecting the Congressional Budget Office’s 10-year planning horizon. Was this a ten year number or a one year number? My guess is the former, but I really don’t know. Hey, so we’re off by a factor of ten, what’s the big deal?

But it gets worse. What’s the need here? Anyone know how far $15 billion will go over either a one year or ten year horizon?

To fill in the perspective a serious reporter would have given, the average annual health care costs for the 10 percent most costly patients is more than $50,000 a year. We’re talking about 32 million people, so that comes to more than $1.5 trillion a year.

Many of these people are on Medicare, and some are covered by employer provided insurance, so many will not end up in these high risk pools and need subsidies. But, let’s say that one third of them do end up in these pools. That means the cost would be $500 billion a year for these folks’ health care. Mr. Johnson is proposing a subsidy of between $1.5 billion and $15 billion to help these people cover their insurance.

Got the picture now?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post editorial page is of course famous for absurdly claiming that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 in an editorial defending NAFTA. (According to the I.M.F, Mexico’s GDP increased by 83 percent over this period.) Incredibly, the paper still has not corrected this egregious error in its online version.

This is why it is difficult to share the concern of Fred Hiatt, the editorial page editor, that we will see increasingly dishonest public debates. Hiatt and his team at the editorial page have no qualms at all about making up nonsense when pushing their positions. While I’m a big fan of facts and data in public debate, the Post’s editorial page editor is about the last person in the world who should be complaining about dishonest arguments.

Just to pick a trivial point in this piece, Hiatt wants us to be concerned about automation displacing workers. As fans of data know, automation is actually advancing at a record slow pace, with productivity growth averaging just 1.0 percent over the last decade. (This compares to 3.0 percent in the 1947 to 1973 Golden Age and the pick-up from 1995 to 2005.)

If Hiatt is predicting an imminent pick-up, as do some techno-optimists, then he was being dishonest in citing projections from the Congressional Budget Office showing larger budget deficits. If productivity picks up, so will growth and tax revenue, making the budget picture much brighter than what CBO is projecting.

It is also striking to see Hiatt warning about automation, the day after the Post editorial page complained that too many people have stopped working because of an overly generous disability program. That piece told readers:

“…at a time of declining workforce participation, especially among so-called prime-age males (those between 25 and 54 years old), the nation’s long-term economic potential depends on making sure work pays for all those willing to work. And from that point of view, the Social Security disability program needs reform.”

Okay, so yesterday we had too few workers and today we have too many because of automation. These arguments are complete opposites. The one unifying theme is that the Post is worried that we are being too generous to the poor and middle class.

The Washington Post editorial page is of course famous for absurdly claiming that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 in an editorial defending NAFTA. (According to the I.M.F, Mexico’s GDP increased by 83 percent over this period.) Incredibly, the paper still has not corrected this egregious error in its online version.

This is why it is difficult to share the concern of Fred Hiatt, the editorial page editor, that we will see increasingly dishonest public debates. Hiatt and his team at the editorial page have no qualms at all about making up nonsense when pushing their positions. While I’m a big fan of facts and data in public debate, the Post’s editorial page editor is about the last person in the world who should be complaining about dishonest arguments.

Just to pick a trivial point in this piece, Hiatt wants us to be concerned about automation displacing workers. As fans of data know, automation is actually advancing at a record slow pace, with productivity growth averaging just 1.0 percent over the last decade. (This compares to 3.0 percent in the 1947 to 1973 Golden Age and the pick-up from 1995 to 2005.)

If Hiatt is predicting an imminent pick-up, as do some techno-optimists, then he was being dishonest in citing projections from the Congressional Budget Office showing larger budget deficits. If productivity picks up, so will growth and tax revenue, making the budget picture much brighter than what CBO is projecting.

It is also striking to see Hiatt warning about automation, the day after the Post editorial page complained that too many people have stopped working because of an overly generous disability program. That piece told readers:

“…at a time of declining workforce participation, especially among so-called prime-age males (those between 25 and 54 years old), the nation’s long-term economic potential depends on making sure work pays for all those willing to work. And from that point of view, the Social Security disability program needs reform.”

Okay, so yesterday we had too few workers and today we have too many because of automation. These arguments are complete opposites. The one unifying theme is that the Post is worried that we are being too generous to the poor and middle class.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión