There was probably too much made out of the slowing in payroll employment growth in the March jobs numbers reported yesterday. This was likely driven in large part by the unusually good weather in January and February that brought a lot of spring hiring forward. However, there were a couple of items that did not get the attention they deserve.

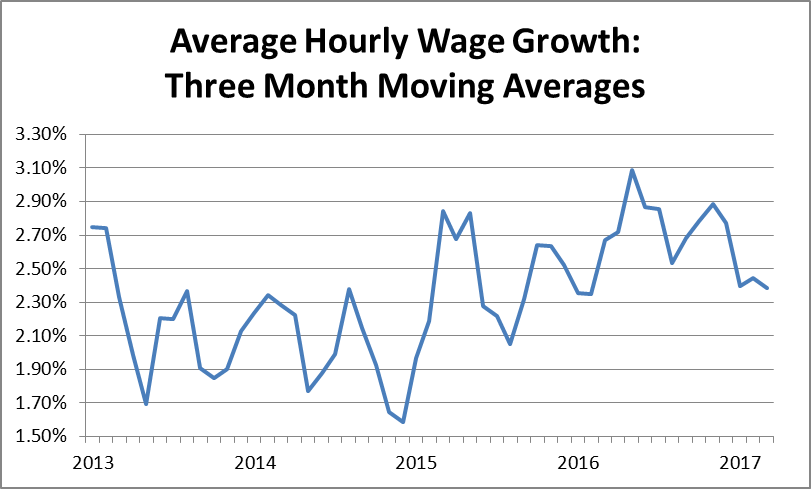

First, there is some limited evidence that wage growth is slowing. Typically, the year-over-year change in the average hourly wage is reported. While the growth in this measure slowed slightly last month, a problem with the year-over-year rate is that it reflects wage growth over the last year, not just recent months. I prefer taking the annualized rate of growth for the average of the last three months compared with the average of the prior three months. This measure can be sensitive to erratic month-to-month changes, but at least it focuses on a more recent period, rather than telling us about the wage growth from nine or ten months ago.

Here’s the picture using this series since the start of 2013.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As the figure shows, there was some very modest increase in the rate of wage growth in early 2016, with a peak of 3.1 percent in May of 2016. Since then, the general direction has been downward, with the rate over the last three months being less than 2.5 percent. This matters hugely for the Fed’s interest rate policy, since a main issue for those looking to raise rates is that inflation could start rising above target levels. That seems unlikely if the rate of wage growth is stable or slowing.

In this respect it is also worth noting that the Employment Cost Index (ECI), a broader measure of compensation that includes non-wage benefits like health care, shows zero evidence of acceleration over this period. Over the last twelve months the ECI has risen 2.2 percent. That is the same rate of increase as we saw in this index three years earlier.

In short, you really can’t find any evidence of accelerating wage growth in the data. The evidence of deceleration is too weak to say anything conclusive, but if anything, wage growth is going in the wrong direction to make the case for the inflation hawks.

The other item that deserved more attention in the jobs report was the rise in the employment rate (EPOP) of prime-age workers. This rose by 0.2 percentage points to 78.5 percent. This number is 0.5 percentage points above its year-ago level, although still 1.8 percentage points below the pre-recession peak and almost 4.0 percentage points below the 2000 peak. This suggests that the EPOP could still rise much further before we can say that we have reached full employment.

There was also an interesting gender split to the rise in the EPOP. While the EPOP for prime-age women is up a full percentage point from its year, the EPOP for prime-age men is unchanged. This could begin to look like the widely hyped problem with men story, if the trend continues.

However, there are two important caveats. First, the monthly data are erratic. If we take three month averages, the year over year increase in EPOPs for men would be 0.2 percentage points and for women it would be 0.8 percentage points. This is still a substantial difference, but at least the rate for men is moving in the right direction.

The other issue is that, at least from the summary data, it does not appear to be an issue with less-educated men. Over the last year, the EPOP for people with college degrees is actually down by 0.3 percentage points in the first three months of 2017 compared to 2016. By contrast, the EPOP for people with just a high school degree is up by 0.3 percentage points. It is possible that a further analysis would show large gender differences, but it seems unlikely that the weakness in EPOPs could be concentrated among less educated men, given these numbers. This seems especially unlikely given that the retirement of baby boomers would be primarily affecting the EPOPs of people with just a high school degree.

There was probably too much made out of the slowing in payroll employment growth in the March jobs numbers reported yesterday. This was likely driven in large part by the unusually good weather in January and February that brought a lot of spring hiring forward. However, there were a couple of items that did not get the attention they deserve.

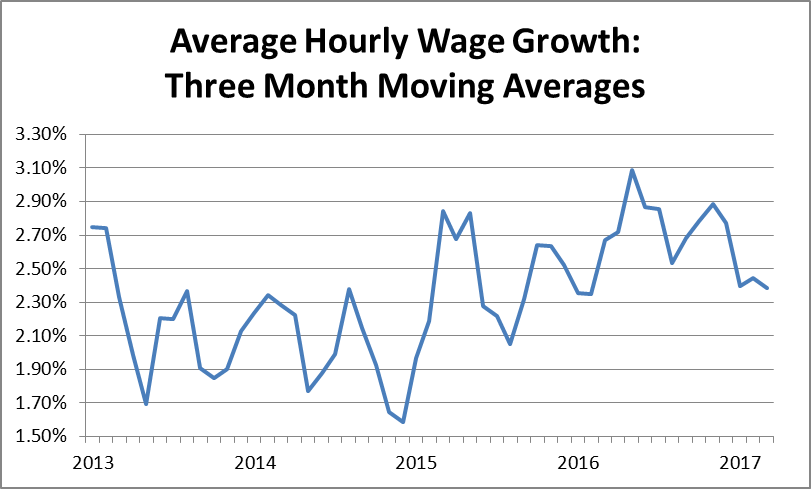

First, there is some limited evidence that wage growth is slowing. Typically, the year-over-year change in the average hourly wage is reported. While the growth in this measure slowed slightly last month, a problem with the year-over-year rate is that it reflects wage growth over the last year, not just recent months. I prefer taking the annualized rate of growth for the average of the last three months compared with the average of the prior three months. This measure can be sensitive to erratic month-to-month changes, but at least it focuses on a more recent period, rather than telling us about the wage growth from nine or ten months ago.

Here’s the picture using this series since the start of 2013.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As the figure shows, there was some very modest increase in the rate of wage growth in early 2016, with a peak of 3.1 percent in May of 2016. Since then, the general direction has been downward, with the rate over the last three months being less than 2.5 percent. This matters hugely for the Fed’s interest rate policy, since a main issue for those looking to raise rates is that inflation could start rising above target levels. That seems unlikely if the rate of wage growth is stable or slowing.

In this respect it is also worth noting that the Employment Cost Index (ECI), a broader measure of compensation that includes non-wage benefits like health care, shows zero evidence of acceleration over this period. Over the last twelve months the ECI has risen 2.2 percent. That is the same rate of increase as we saw in this index three years earlier.

In short, you really can’t find any evidence of accelerating wage growth in the data. The evidence of deceleration is too weak to say anything conclusive, but if anything, wage growth is going in the wrong direction to make the case for the inflation hawks.

The other item that deserved more attention in the jobs report was the rise in the employment rate (EPOP) of prime-age workers. This rose by 0.2 percentage points to 78.5 percent. This number is 0.5 percentage points above its year-ago level, although still 1.8 percentage points below the pre-recession peak and almost 4.0 percentage points below the 2000 peak. This suggests that the EPOP could still rise much further before we can say that we have reached full employment.

There was also an interesting gender split to the rise in the EPOP. While the EPOP for prime-age women is up a full percentage point from its year, the EPOP for prime-age men is unchanged. This could begin to look like the widely hyped problem with men story, if the trend continues.

However, there are two important caveats. First, the monthly data are erratic. If we take three month averages, the year over year increase in EPOPs for men would be 0.2 percentage points and for women it would be 0.8 percentage points. This is still a substantial difference, but at least the rate for men is moving in the right direction.

The other issue is that, at least from the summary data, it does not appear to be an issue with less-educated men. Over the last year, the EPOP for people with college degrees is actually down by 0.3 percentage points in the first three months of 2017 compared to 2016. By contrast, the EPOP for people with just a high school degree is up by 0.3 percentage points. It is possible that a further analysis would show large gender differences, but it seems unlikely that the weakness in EPOPs could be concentrated among less educated men, given these numbers. This seems especially unlikely given that the retirement of baby boomers would be primarily affecting the EPOPs of people with just a high school degree.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It will be great when the NYT and other news outlets stop feeling the need to misrepresent the promoters of the standard trade agenda as “free traders” as they did in a news article discussing Donald Trump’s latest actions on trade. In fact, these people are selective protectionists.

While they are happy to reduce barriers that might protect manufacturing workers from competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, they are fine with the protectionist barriers that maintain the high pay of doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals. (For example, a foreign doctor cannot practice in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program.)

They also support longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. These protections are equivalent to tariffs of thousands of percent on the protected items, most importantly prescription drugs.

The predicted and actual effect of this policy of selective protectionism is to redistribute income upward. Calling it “free trade” gives it a justification it does not deserve.

It will be great when the NYT and other news outlets stop feeling the need to misrepresent the promoters of the standard trade agenda as “free traders” as they did in a news article discussing Donald Trump’s latest actions on trade. In fact, these people are selective protectionists.

While they are happy to reduce barriers that might protect manufacturing workers from competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, they are fine with the protectionist barriers that maintain the high pay of doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals. (For example, a foreign doctor cannot practice in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program.)

They also support longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. These protections are equivalent to tariffs of thousands of percent on the protected items, most importantly prescription drugs.

The predicted and actual effect of this policy of selective protectionism is to redistribute income upward. Calling it “free trade” gives it a justification it does not deserve.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is always open to plans for taking money from ordinary workers and giving it to the rich. For this reason it was not surprising to see a piece by Robert Atkinson, the head of the industry funded Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, advocating for more protectionism in the form of stronger and longer patent and copyright monopolies.

These monopolies, legacies from the medieval guild system, can raise the price of the protected items by one or two orders of magnitudes making them equivalent to tariffs of several hundred or several thousand percent. They are especially important in the case of prescription drugs.

Life-saving drugs that would sell for $200 or $300 in a free market can sell for tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars due to patent protection. The country will spend over $440 billion this year for drugs that would likely sell for less than $80 billion in a free market. The strengthening of these protections is an important cause of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. The difference comes to more than $2,700 a year for an average family. (This is discussed in chapter 5 of Rigged, where I also lay out alternative mechanisms for financing innovation and creative work.)

Atkinson makes this argument in the context of the U.S. relationship with China. He also is explicitly prepared to have ordinary workers pay the price for this protectionism. He warns that not following his recommendation for a new approach to dealing with China, including forcing them to impose more protection for U.S. patents and copyrights, would lead to a lower valued dollar.

Of course, a lower valued dollar will make U.S. goods and services more competitive internationally. That would mean a smaller trade deficit as we sell more manufactured goods elsewhere in the world and buy fewer imported goods in the United States. This could increase manufacturing employment by 1–2 million, putting upward pressure on the wages of non-college educated workers.

In short, not following Atkinson’s path is likely to mean more money for less-educated workers, less money for the rich, and more overall growth, as the economy benefits from the lessening of protectionist barriers.

The Washington Post is always open to plans for taking money from ordinary workers and giving it to the rich. For this reason it was not surprising to see a piece by Robert Atkinson, the head of the industry funded Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, advocating for more protectionism in the form of stronger and longer patent and copyright monopolies.

These monopolies, legacies from the medieval guild system, can raise the price of the protected items by one or two orders of magnitudes making them equivalent to tariffs of several hundred or several thousand percent. They are especially important in the case of prescription drugs.

Life-saving drugs that would sell for $200 or $300 in a free market can sell for tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars due to patent protection. The country will spend over $440 billion this year for drugs that would likely sell for less than $80 billion in a free market. The strengthening of these protections is an important cause of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. The difference comes to more than $2,700 a year for an average family. (This is discussed in chapter 5 of Rigged, where I also lay out alternative mechanisms for financing innovation and creative work.)

Atkinson makes this argument in the context of the U.S. relationship with China. He also is explicitly prepared to have ordinary workers pay the price for this protectionism. He warns that not following his recommendation for a new approach to dealing with China, including forcing them to impose more protection for U.S. patents and copyrights, would lead to a lower valued dollar.

Of course, a lower valued dollar will make U.S. goods and services more competitive internationally. That would mean a smaller trade deficit as we sell more manufactured goods elsewhere in the world and buy fewer imported goods in the United States. This could increase manufacturing employment by 1–2 million, putting upward pressure on the wages of non-college educated workers.

In short, not following Atkinson’s path is likely to mean more money for less-educated workers, less money for the rich, and more overall growth, as the economy benefits from the lessening of protectionist barriers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There have been several news accounts in recent days of plans for the Federal Reserve Board to reduce the amount of assets on its balance sheets. It currently holds close to $4 trillion in assets as a result of the quantitative easing policies pursued to boost the economy in the years following the collapse of the housing bubble. It is now making plans to reduce these holdings.

One implication of this reduction in holdings would be a lower amount of money refunded to the Treasury each year. The Fed keeps some of the interest from these holdings to pay operating expenses and pay a dividend to its members, but the overwhelming majority is refunded back to the Treasury.

Last year, the Fed refunded $113 billion or 0.6 percent of GDP to the Treasury (Table 4-1). According to the projections from the Congressional Budget Office, this figure is projected to fall sharply to 0.2 percent of GDP in the next couple of years as the Fed reduces its holdings. Over the course of a decade, the difference in the amount rebated to the Treasury between a scenario where the Fed continues to hold $4 trillion in assets and one in which most of the assets are sold to the public would be on the order of $900 billion.

Deficit hawks routinely get very excited over sums that are less than one tenth of this size. For this reason it seems worth mentioning the budgetary implications of the Fed’s decision to offload its asset holdings. (For those keeping score, having the Fed keep the assets is equivalent to financing the debt in part by printing money, a position advocated by several prominent economists, including Ben Bernanke.)

There have been several news accounts in recent days of plans for the Federal Reserve Board to reduce the amount of assets on its balance sheets. It currently holds close to $4 trillion in assets as a result of the quantitative easing policies pursued to boost the economy in the years following the collapse of the housing bubble. It is now making plans to reduce these holdings.

One implication of this reduction in holdings would be a lower amount of money refunded to the Treasury each year. The Fed keeps some of the interest from these holdings to pay operating expenses and pay a dividend to its members, but the overwhelming majority is refunded back to the Treasury.

Last year, the Fed refunded $113 billion or 0.6 percent of GDP to the Treasury (Table 4-1). According to the projections from the Congressional Budget Office, this figure is projected to fall sharply to 0.2 percent of GDP in the next couple of years as the Fed reduces its holdings. Over the course of a decade, the difference in the amount rebated to the Treasury between a scenario where the Fed continues to hold $4 trillion in assets and one in which most of the assets are sold to the public would be on the order of $900 billion.

Deficit hawks routinely get very excited over sums that are less than one tenth of this size. For this reason it seems worth mentioning the budgetary implications of the Fed’s decision to offload its asset holdings. (For those keeping score, having the Fed keep the assets is equivalent to financing the debt in part by printing money, a position advocated by several prominent economists, including Ben Bernanke.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had an interesting piece that reported on the ways in which Uber uses techniques learned from behaviorial economics to get drivers to work longer hours than they might want. The article concludes by saying that with changes in the economy, many workers may have no choice but to rely on Uber jobs.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the Federal Reserve Board. The Federal Reserve Board has raised interest rates twice in the last four months because it is concerned that the economy is creating too many jobs. It is expected to raise interest rates three more times this year.

If people consider it bad that workers have few options other than working for Uber, they should be very upset that the Fed is raising interest rates. These interest rates are helping to ensure that millions of workers have limited job opportunities.

The New York Times had an interesting piece that reported on the ways in which Uber uses techniques learned from behaviorial economics to get drivers to work longer hours than they might want. The article concludes by saying that with changes in the economy, many workers may have no choice but to rely on Uber jobs.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the Federal Reserve Board. The Federal Reserve Board has raised interest rates twice in the last four months because it is concerned that the economy is creating too many jobs. It is expected to raise interest rates three more times this year.

If people consider it bad that workers have few options other than working for Uber, they should be very upset that the Fed is raising interest rates. These interest rates are helping to ensure that millions of workers have limited job opportunities.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Most people involved in economic policy debates have derided Donald Trump’s claims that he would boost the U.S. growth rate from its recent 2.0 percent annual rate to 4.0 percent or even 3.0 percent. However the Washington Post featured a column today that insists such a pickup is imminent and derides policy types for not being prepared.

The article insists that we are about to see massive job displacement with robots and artificial intelligence radically reducing the need for human labor. If it is not immediately clear that this is a prediction that growth is about to boom, then you must be as ignorant as a Washington Post editorial page writer.

Job displacement means productivity growth. If the piece is correct then we are about to see a massive upsurge in productivity growth. The recent pace has been just 1.0 percent annually. The authors presumably envision productivity growth rising to something like the 3.0 percent annual rate we had in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973, a period of low unemployment and rapidly rising real wages.

Economic growth is the sum of productivity growth and labor force growth, so if we get productivity growth of 3.0 percent annually, then we are looking at GDP growth rates in line with Donald Trump’s targets. Of course this would mean that the Congressional Budget Office and all the other forecasters are hugely off (hardly impossible, they all missed the collapse of the housing bubble as well as the weakness of the recovery that followed) and that concerns about large budget deficits are incredibly misplaced.

For my part, I am agnostic on these predictions of a massive surge in productivity growth. Our past efforts at predicting productivity growth have been virtually worthless. Economists completely missed the slowdown in 1973, almost completely missed the pickup in 1995, and totally missed the more recent slowdown in 2005.

I think much of the story is endogenous in the sense that a weak labor market forces workers to take low pay and low productivity jobs. In other words, if we pushed the economy with more spending (e.g. larger budget deficits or smaller trade deficits) we would see more productivity growth as workers shifted to better paying, higher productivity jobs, and firms adjusted to a more expensive workforce with labor saving innovations.

But speculation aside, we should at least be able to have clear thinking on the issue. If we actually face massive job displacement due to technology, then we are looking at a period of rapid growth in which budget deficits are not at all a problem. This is not a debatable proposition, it is true in the same way that 3+2 = 5 is true. It would be great if the people involved in policy debates understood this fact.

Most people involved in economic policy debates have derided Donald Trump’s claims that he would boost the U.S. growth rate from its recent 2.0 percent annual rate to 4.0 percent or even 3.0 percent. However the Washington Post featured a column today that insists such a pickup is imminent and derides policy types for not being prepared.

The article insists that we are about to see massive job displacement with robots and artificial intelligence radically reducing the need for human labor. If it is not immediately clear that this is a prediction that growth is about to boom, then you must be as ignorant as a Washington Post editorial page writer.

Job displacement means productivity growth. If the piece is correct then we are about to see a massive upsurge in productivity growth. The recent pace has been just 1.0 percent annually. The authors presumably envision productivity growth rising to something like the 3.0 percent annual rate we had in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973, a period of low unemployment and rapidly rising real wages.

Economic growth is the sum of productivity growth and labor force growth, so if we get productivity growth of 3.0 percent annually, then we are looking at GDP growth rates in line with Donald Trump’s targets. Of course this would mean that the Congressional Budget Office and all the other forecasters are hugely off (hardly impossible, they all missed the collapse of the housing bubble as well as the weakness of the recovery that followed) and that concerns about large budget deficits are incredibly misplaced.

For my part, I am agnostic on these predictions of a massive surge in productivity growth. Our past efforts at predicting productivity growth have been virtually worthless. Economists completely missed the slowdown in 1973, almost completely missed the pickup in 1995, and totally missed the more recent slowdown in 2005.

I think much of the story is endogenous in the sense that a weak labor market forces workers to take low pay and low productivity jobs. In other words, if we pushed the economy with more spending (e.g. larger budget deficits or smaller trade deficits) we would see more productivity growth as workers shifted to better paying, higher productivity jobs, and firms adjusted to a more expensive workforce with labor saving innovations.

But speculation aside, we should at least be able to have clear thinking on the issue. If we actually face massive job displacement due to technology, then we are looking at a period of rapid growth in which budget deficits are not at all a problem. This is not a debatable proposition, it is true in the same way that 3+2 = 5 is true. It would be great if the people involved in policy debates understood this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Donald Trump’s bluster about imposing large tariffs and forcing companies to make things in America has led to backlash where we have people saying things to the effect that we are in a global economy and we just can’t do anything about shifting from foreign produced items to domestically produced items. Paul Krugman’s blog post on trade can be seen in this light, although it is not exactly what he said and he surely knows better.

The post points out that imports account for a large percentage of the cost of many of the goods we produce here. This means that if we raise the price of imports, we also make it more expensive to produce goods in the United States.

This is of course true, but that doesn’t mean that higher import prices would not lead to a shift towards domestic production. For example, if we take the case of transport equipment he highlights, if all the parts that we imported cost 20 percent more, then over time we would expect car producers in the United States to produce with a larger share of domestically produced parts than would otherwise be the case. This doesn’t mean that imported parts go to zero, or even that they necessarily fall, but just that they would be less than would be the case if import prices were 20 percent lower. This is pretty much basic economics — at a higher price we buy less.

While arbitrary tariffs are not a good way to raise the relative price of imports, we do have an obvious tool that is designed for exactly this purpose. We can reduce the value of the dollar against the currencies of our trading partners. This is probably best done through negotiations, which would inevitably involve trade-offs (e.g. less pressure to enforce U.S. patents and copyrights and less concern about access for the U.S. financial industry). Loud threats against our trading partners are likely to prove counter-productive. (We should also remove the protectionist barriers that keep our doctors and dentists from enjoying the full benefits of international competition.)

Anyhow, we can do something about our trade deficits if we had a president who thought seriously about the issue. As it is, the current occupant of the White House seems to not know which way is up when it comes to trade.

Donald Trump’s bluster about imposing large tariffs and forcing companies to make things in America has led to backlash where we have people saying things to the effect that we are in a global economy and we just can’t do anything about shifting from foreign produced items to domestically produced items. Paul Krugman’s blog post on trade can be seen in this light, although it is not exactly what he said and he surely knows better.

The post points out that imports account for a large percentage of the cost of many of the goods we produce here. This means that if we raise the price of imports, we also make it more expensive to produce goods in the United States.

This is of course true, but that doesn’t mean that higher import prices would not lead to a shift towards domestic production. For example, if we take the case of transport equipment he highlights, if all the parts that we imported cost 20 percent more, then over time we would expect car producers in the United States to produce with a larger share of domestically produced parts than would otherwise be the case. This doesn’t mean that imported parts go to zero, or even that they necessarily fall, but just that they would be less than would be the case if import prices were 20 percent lower. This is pretty much basic economics — at a higher price we buy less.

While arbitrary tariffs are not a good way to raise the relative price of imports, we do have an obvious tool that is designed for exactly this purpose. We can reduce the value of the dollar against the currencies of our trading partners. This is probably best done through negotiations, which would inevitably involve trade-offs (e.g. less pressure to enforce U.S. patents and copyrights and less concern about access for the U.S. financial industry). Loud threats against our trading partners are likely to prove counter-productive. (We should also remove the protectionist barriers that keep our doctors and dentists from enjoying the full benefits of international competition.)

Anyhow, we can do something about our trade deficits if we had a president who thought seriously about the issue. As it is, the current occupant of the White House seems to not know which way is up when it comes to trade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión