The Peter Peterson Gang and its accomplices like to scare people with talk of the extraordinarily high debt-to-GDP ratio. As folks familiar with economics know, the nominal value of the debt means almost nothing. Insofar as we can talk meaningfully of a burden being imposed on our children it would be the interest that we have to pay on the debt. This is actually near a post-war low measured as a share of GDP. This measure nets out the interest payments that are rebated from the Fed to the Treasury, so it is somewhat different than the measure of net interest often shown.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Of course, the interest burden of the debt is just one way that we make commitments for future generations. When the government grants patent and copyright monopolies it is allowing companies to charge prices that are far above the free market price for their products. This is effectively a privately collected tax. The sums involved are quite large. In the case of prescription drugs alone we pay $430 billion a year for drugs that would cost around $60 billion in a free market. The difference of $370 billion is almost 2.0 percent of GDP, a sum that is more than twice as large as the interest burden on the debt.

We do need to provided an incentive for research (see Rigged, chapter 5 — it’s free), but there are almost certainly more efficient mechanisms for providing incentives than patent protection, at least for prescription drugs. But more importantly for the issue at hand is that the government is obligating these payments long into the future.

If we are worried about the well-being of our children, the fact that the government is making them pay an extra $370 billion a year for drugs, and much more for other items as well, should be every bit as concerning as if the government raised taxes itself by $370 billion a year. Of course, this assumes that the issue is actually a concern for the well-being of our children. If the goal is to scare people into supporting cuts to Social Security and Medicare, then the debt-to-GDP ratio is the right measure.

The Peter Peterson Gang and its accomplices like to scare people with talk of the extraordinarily high debt-to-GDP ratio. As folks familiar with economics know, the nominal value of the debt means almost nothing. Insofar as we can talk meaningfully of a burden being imposed on our children it would be the interest that we have to pay on the debt. This is actually near a post-war low measured as a share of GDP. This measure nets out the interest payments that are rebated from the Fed to the Treasury, so it is somewhat different than the measure of net interest often shown.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Of course, the interest burden of the debt is just one way that we make commitments for future generations. When the government grants patent and copyright monopolies it is allowing companies to charge prices that are far above the free market price for their products. This is effectively a privately collected tax. The sums involved are quite large. In the case of prescription drugs alone we pay $430 billion a year for drugs that would cost around $60 billion in a free market. The difference of $370 billion is almost 2.0 percent of GDP, a sum that is more than twice as large as the interest burden on the debt.

We do need to provided an incentive for research (see Rigged, chapter 5 — it’s free), but there are almost certainly more efficient mechanisms for providing incentives than patent protection, at least for prescription drugs. But more importantly for the issue at hand is that the government is obligating these payments long into the future.

If we are worried about the well-being of our children, the fact that the government is making them pay an extra $370 billion a year for drugs, and much more for other items as well, should be every bit as concerning as if the government raised taxes itself by $370 billion a year. Of course, this assumes that the issue is actually a concern for the well-being of our children. If the goal is to scare people into supporting cuts to Social Security and Medicare, then the debt-to-GDP ratio is the right measure.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Readers of the NYT article on Donald Trump’s pick to be Secretary of Health and Human Services might have gotten this impression. The piece told readers:

“His [Price’s] resentment of government intervention in medicine drove Mr. Price to become involved in the Medical Association of Georgia early in his career, and his work there led him to run for office in 1995, when the House seat in his district opened up.”

If Mr. Price really does resent government intervention then surely he would be outraged by protectionist rules that prohibit hundreds of thousands of qualified doctors from practicing medicine in the United States and bringing doctors’ pay in line with pay in other wealthy countries. (Doctors can’t practice medicine in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program.)

Presumably, Mr. Price is also outraged by government granted patent monopolies that raise drugs by ten or even a hundred times their free market price. These protections are equivalent to tariffs of several thousand percent. The story is the same with medical equipment which is also made expensive by these government interventions. (We need a mechanism to pay for innovation, but there are more efficient routes. See Rigged, chapter 5 [it’s free]).

If Mr. Price doesn’t object to protectionism for doctors and drug companies then the NYT is wrong in saying that he has resentment of government intervention in medicine. It seems more plausible that Price resents government actions that reduce the incomes of doctors. It would be helpful if the Times did not confuse these issues.

Readers of the NYT article on Donald Trump’s pick to be Secretary of Health and Human Services might have gotten this impression. The piece told readers:

“His [Price’s] resentment of government intervention in medicine drove Mr. Price to become involved in the Medical Association of Georgia early in his career, and his work there led him to run for office in 1995, when the House seat in his district opened up.”

If Mr. Price really does resent government intervention then surely he would be outraged by protectionist rules that prohibit hundreds of thousands of qualified doctors from practicing medicine in the United States and bringing doctors’ pay in line with pay in other wealthy countries. (Doctors can’t practice medicine in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program.)

Presumably, Mr. Price is also outraged by government granted patent monopolies that raise drugs by ten or even a hundred times their free market price. These protections are equivalent to tariffs of several thousand percent. The story is the same with medical equipment which is also made expensive by these government interventions. (We need a mechanism to pay for innovation, but there are more efficient routes. See Rigged, chapter 5 [it’s free]).

If Mr. Price doesn’t object to protectionism for doctors and drug companies then the NYT is wrong in saying that he has resentment of government intervention in medicine. It seems more plausible that Price resents government actions that reduce the incomes of doctors. It would be helpful if the Times did not confuse these issues.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Max Ehrenfreund features a rather silly debate among economists about explanations for the housing bubble (wrongly described as the “financial” crisis) in a Wonkblog piece. The debate is over whether subprime mortgages were central to the bubble. Of course, subprime played an important role, but the focus of the piece is on new research showing that most of the bad debt was on prime mortgages taken out by people with good credit records.

I sort of thought everyone knew this, but whatever. The more important point is that economists continue to treat the housing bubble as something that snuck up on us in the dark and only someone with an incredibly keen sense of the housing market would have seen it. (I focus on the bubble and not the financial crisis, because the latter was very much secondary and really a distraction. By 2011, our financial system had been pretty much fully mended, yet the weak economy persisted. This was due to the fact that we had no source of demand in the economy to replace the demand generated by the housing bubble.)

Anyhow, there was nothing mysterious about the housing bubble. We had an unprecedented run-up in real house prices with no remotely plausible explanation in the fundamentals of the housing market. This could be clearly seen by the fact that rents were just following in step with the overall rate of inflation, as they have generally for as long as we have data. (This is nationwide, rents have outpaced inflation in many local markets, as have house prices.) The bubble should also have been apparent as we had record vacancy rates as early as 2002. The vacancy rate eventually rose much higher by the peak of the market in 2006.

It should also have been clear that the collapse of the bubble would be bad news for the economy. Residential construction reached a peak of 6.5 percent of GDP, about 2.5 percentage points more than normal. (When the bubble burst it fell to less than 2.0 percent of GDP due to massive overbuilding.) Also, the housing wealth effect led to an enormous consumption boom as people spent based on $8 trillion in ephemeral housing wealth.

In short, there was really no excuse for economists missing the bubble or not recognizing the fact that its collapse would lead to a severe recession. The signs were very visible to any competent observer.

Max Ehrenfreund features a rather silly debate among economists about explanations for the housing bubble (wrongly described as the “financial” crisis) in a Wonkblog piece. The debate is over whether subprime mortgages were central to the bubble. Of course, subprime played an important role, but the focus of the piece is on new research showing that most of the bad debt was on prime mortgages taken out by people with good credit records.

I sort of thought everyone knew this, but whatever. The more important point is that economists continue to treat the housing bubble as something that snuck up on us in the dark and only someone with an incredibly keen sense of the housing market would have seen it. (I focus on the bubble and not the financial crisis, because the latter was very much secondary and really a distraction. By 2011, our financial system had been pretty much fully mended, yet the weak economy persisted. This was due to the fact that we had no source of demand in the economy to replace the demand generated by the housing bubble.)

Anyhow, there was nothing mysterious about the housing bubble. We had an unprecedented run-up in real house prices with no remotely plausible explanation in the fundamentals of the housing market. This could be clearly seen by the fact that rents were just following in step with the overall rate of inflation, as they have generally for as long as we have data. (This is nationwide, rents have outpaced inflation in many local markets, as have house prices.) The bubble should also have been apparent as we had record vacancy rates as early as 2002. The vacancy rate eventually rose much higher by the peak of the market in 2006.

It should also have been clear that the collapse of the bubble would be bad news for the economy. Residential construction reached a peak of 6.5 percent of GDP, about 2.5 percentage points more than normal. (When the bubble burst it fell to less than 2.0 percent of GDP due to massive overbuilding.) Also, the housing wealth effect led to an enormous consumption boom as people spent based on $8 trillion in ephemeral housing wealth.

In short, there was really no excuse for economists missing the bubble or not recognizing the fact that its collapse would lead to a severe recession. The signs were very visible to any competent observer.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ivan Krastev, a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, had an interesting NYT column on the disenchantment of the European public with the meritocrats who have been largely running governments there for the last three decades. Krastev’s main conclusion is that the public doesn’t identify with an internationally-oriented group of meritocrats who possess skills that are easily transferable from their home country to other countries.

While this lack of sufficient national identity may play a role in the dislike of the meritocrats, there is a much simpler explanation: they have done a horrible job. Much of Europe continues to suffer from high unemployment, or low employment rates, almost a decade after the collapse of housing bubbles sent the continent’s economy in a downward spiral. The meritocrats deserve the blame for both the weak recovery and allowing dangerous bubbles to grow in the first place. In most countries, most of the population has seen declining incomes over the last decade in spite of the substantial technological progress we have seen over this period.

Incredibly, Krastev writes of this failure of the meritocrats as though it is just something that happened as opposed to something they did.

“But what happens when these teams start to lose or the economy slows down? Their fans abandon them.”

Of course the economy didn’t just slow down, the meritocrats mismanaged it. It is not surprising that the public would want to turn away from experts who perform badly in their area of expertise, even if they might be really smart. The fact that almost none of the experts acknowledge their failure and instead look to blame it on impersonal forces, like technology, is not likely to further endear them to workers who are used to be held responsible for the quality of their work.

Ivan Krastev, a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, had an interesting NYT column on the disenchantment of the European public with the meritocrats who have been largely running governments there for the last three decades. Krastev’s main conclusion is that the public doesn’t identify with an internationally-oriented group of meritocrats who possess skills that are easily transferable from their home country to other countries.

While this lack of sufficient national identity may play a role in the dislike of the meritocrats, there is a much simpler explanation: they have done a horrible job. Much of Europe continues to suffer from high unemployment, or low employment rates, almost a decade after the collapse of housing bubbles sent the continent’s economy in a downward spiral. The meritocrats deserve the blame for both the weak recovery and allowing dangerous bubbles to grow in the first place. In most countries, most of the population has seen declining incomes over the last decade in spite of the substantial technological progress we have seen over this period.

Incredibly, Krastev writes of this failure of the meritocrats as though it is just something that happened as opposed to something they did.

“But what happens when these teams start to lose or the economy slows down? Their fans abandon them.”

Of course the economy didn’t just slow down, the meritocrats mismanaged it. It is not surprising that the public would want to turn away from experts who perform badly in their area of expertise, even if they might be really smart. The fact that almost none of the experts acknowledge their failure and instead look to blame it on impersonal forces, like technology, is not likely to further endear them to workers who are used to be held responsible for the quality of their work.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I blogged yesterday on how “Davos Man,” the world’s super-rich, is very supportive of all sorts of protectionist measures in spite of his reputation as a free trader. I pointed out that Davos Man is fond of items like ever stronger and longer patent and copyright protections and measures that protect doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals. Davos Man only dislikes protectionism when it might benefit folks like autoworkers or textile workers.

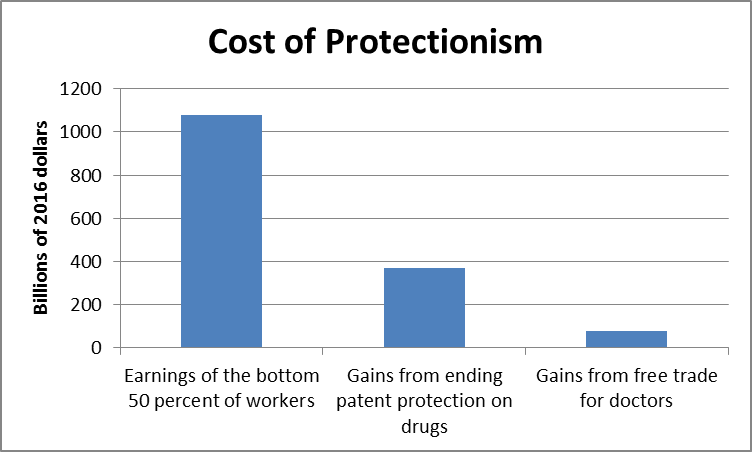

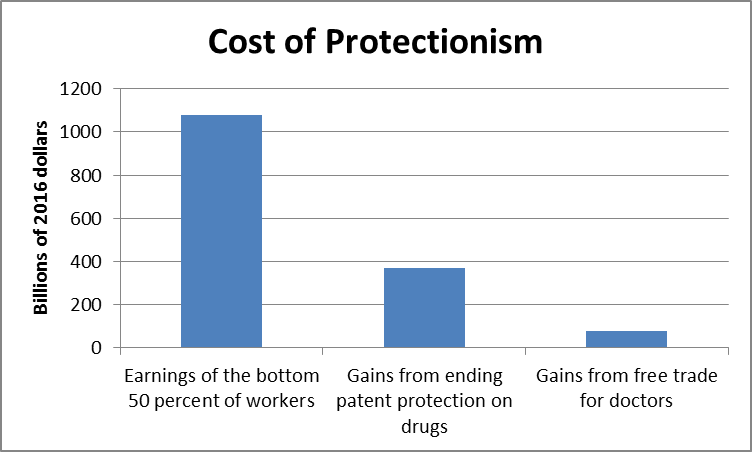

I thought it was worth pointing out that the protectionism supported by the Davos set is real money. The chart below shows the additional amount we pay for prescription drugs each year as a result of patent and related protections, the additional amount we pay for physicians as a result of excluding qualified foreign doctors, and the total annual wage income for the bottom 50 percent of wage earners. (I added 5 percent to the 2015 wage numbers to incorporate wage growth in the last year.)

Source: Baker 2016 and Social Security Administration.

Source: Baker 2016 and Social Security Administration.

As can be seen, the extra amount we pay for doctors as a result of excluding foreign competition is more than 7 percent of the total wage bill for the bottom half of all wage earners. The extra amount we pay for drugs as a result of patent protection is roughly one third of the total wage bill for the bottom half of wage earners. Of course, we would have to pay for the research through another mechanism, but we also pay higher prices for medical equipment, software, and a wide variety of other products as a result of patent and copyright protections. In other words, there is real money here.

Davos Man isn’t interested in nickel and dime protectionism, he wants to rake in the big bucks. And, the whole time he will run around saying he is a free trader (and get most of the media to believe him).

Note: This is corrected from an earlier version which used a much lower figure for the wage bill for the bottom half of the workforce. Thanks to Nate Fritz for calling this to my attention.

I blogged yesterday on how “Davos Man,” the world’s super-rich, is very supportive of all sorts of protectionist measures in spite of his reputation as a free trader. I pointed out that Davos Man is fond of items like ever stronger and longer patent and copyright protections and measures that protect doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals. Davos Man only dislikes protectionism when it might benefit folks like autoworkers or textile workers.

I thought it was worth pointing out that the protectionism supported by the Davos set is real money. The chart below shows the additional amount we pay for prescription drugs each year as a result of patent and related protections, the additional amount we pay for physicians as a result of excluding qualified foreign doctors, and the total annual wage income for the bottom 50 percent of wage earners. (I added 5 percent to the 2015 wage numbers to incorporate wage growth in the last year.)

Source: Baker 2016 and Social Security Administration.

Source: Baker 2016 and Social Security Administration.

As can be seen, the extra amount we pay for doctors as a result of excluding foreign competition is more than 7 percent of the total wage bill for the bottom half of all wage earners. The extra amount we pay for drugs as a result of patent protection is roughly one third of the total wage bill for the bottom half of wage earners. Of course, we would have to pay for the research through another mechanism, but we also pay higher prices for medical equipment, software, and a wide variety of other products as a result of patent and copyright protections. In other words, there is real money here.

Davos Man isn’t interested in nickel and dime protectionism, he wants to rake in the big bucks. And, the whole time he will run around saying he is a free trader (and get most of the media to believe him).

Note: This is corrected from an earlier version which used a much lower figure for the wage bill for the bottom half of the workforce. Thanks to Nate Fritz for calling this to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT decided to tout the risks that higher tariffs could cause serious damage to industry in the UK following Brexit:

“For Mr. Magal [the CEO of an engineering company that makes parts for the car industry], the threat of trade tariffs is forcing him to rethink the structure of his business. The company assembles thermostatic control units for car manufacturers, including Jaguar Land Rover in Britain and Daimler in Germany.

“Tariffs could add anything up to 10 percent to the price of some of his products, an increase he can neither afford to absorb nor pass on. ‘We don’t make 10 percent profit — that’s for sure,’ he said, adding, ‘We won’t be able to increase the price, because the customer will say, “We will buy from the competition.'”

The problem with this story, as conveyed by Mr. Magal, is that the British pound has already fallen by close to 10 percent against the euro since Brexit. This means that even if the EU places a 10 percent tariff on goods from the UK (the highest allowable under the WTO), his company will be in roughly the same position as it was before Brexit. It is also worth noting that the pound rose by roughly 10 percent against the euro over the couse of 2015. This should have seriously hurt Mr. Magal’s business in the UK if it is as sensitive to relative prices as he claims.

It is likely that Brexit will be harmful to the UK economy if it does occur, but many of the claims made before the vote were wrong, most notably there was not an immediate recession. It seems many of the claims being made now are also false.

The NYT decided to tout the risks that higher tariffs could cause serious damage to industry in the UK following Brexit:

“For Mr. Magal [the CEO of an engineering company that makes parts for the car industry], the threat of trade tariffs is forcing him to rethink the structure of his business. The company assembles thermostatic control units for car manufacturers, including Jaguar Land Rover in Britain and Daimler in Germany.

“Tariffs could add anything up to 10 percent to the price of some of his products, an increase he can neither afford to absorb nor pass on. ‘We don’t make 10 percent profit — that’s for sure,’ he said, adding, ‘We won’t be able to increase the price, because the customer will say, “We will buy from the competition.'”

The problem with this story, as conveyed by Mr. Magal, is that the British pound has already fallen by close to 10 percent against the euro since Brexit. This means that even if the EU places a 10 percent tariff on goods from the UK (the highest allowable under the WTO), his company will be in roughly the same position as it was before Brexit. It is also worth noting that the pound rose by roughly 10 percent against the euro over the couse of 2015. This should have seriously hurt Mr. Magal’s business in the UK if it is as sensitive to relative prices as he claims.

It is likely that Brexit will be harmful to the UK economy if it does occur, but many of the claims made before the vote were wrong, most notably there was not an immediate recession. It seems many of the claims being made now are also false.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article on the annual meeting of the world’s super-rich at Davos, Switzerland. It refers to Davos Man as “an economic elite who built unheard-of fortunes on the seemingly high-minded notions of free trade, low taxes and low regulation that they championed.” While “Davos Man” may like to be described this way, it is not an accurate description.

Davos Man is actually totally supportive of protectionism that redistributes income upward. In particular, Davos Man supports stronger and longer patent and copyright protection. These forms of protection raise the price of protected items by factors of tens or hundreds, making them equivalent to tariffs of several thousand percent or even tens of thousands of percent. In the case of prescription drugs, these protections force us to spend more than $430 billion a year (2.3 percent of GDP) on drugs that would likely cost one tenth of this amount if they were sold in a free market. (Yes, we need alternative mechanisms to finance the development of new drugs. These are discussed in my free book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

Davos Man is also just fine with protectionist barriers that raise the cost of physicians services as well as pay of other highly educated professionals. For example, Davos Man has never been known to object to the ban on foreign doctors practicing in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program or the ban on foreign dentists who did not complete a U.S. dental school (or recently a Canadian school). Davos Man is only bothered by protectionist barriers that raise the incomes of autoworkers, textile workers, or other non-college educated workers.

Davos Man is also fine with government regulations that reduce the bargaining power of ordinary workers. For example, Davos Man has not objected to central bank rules that target low inflation even at the cost of raising unemployment. Nor has Davos Man objected to meaningless caps on budget deficits, like those in the European Union, that have kept millions of workers from getting jobs.

Davos Man also strongly supported the bank bailouts in which governments provided trillions of dollars in loans and guarantees to the world’s largest banks in order to protect them from the market. This kept too big to fail banks in business and protected the huge salaries received by their top executives.

In short, Davos Man has no particular interest in a free market or unregulated economic system. They only object to interventions that reduce their income. Of course, Davos Man is happy to have the New York Times and other news outlets describe him as a devotee of the free market, as opposed to simply getting incredibly rich.

The NYT had an article on the annual meeting of the world’s super-rich at Davos, Switzerland. It refers to Davos Man as “an economic elite who built unheard-of fortunes on the seemingly high-minded notions of free trade, low taxes and low regulation that they championed.” While “Davos Man” may like to be described this way, it is not an accurate description.

Davos Man is actually totally supportive of protectionism that redistributes income upward. In particular, Davos Man supports stronger and longer patent and copyright protection. These forms of protection raise the price of protected items by factors of tens or hundreds, making them equivalent to tariffs of several thousand percent or even tens of thousands of percent. In the case of prescription drugs, these protections force us to spend more than $430 billion a year (2.3 percent of GDP) on drugs that would likely cost one tenth of this amount if they were sold in a free market. (Yes, we need alternative mechanisms to finance the development of new drugs. These are discussed in my free book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

Davos Man is also just fine with protectionist barriers that raise the cost of physicians services as well as pay of other highly educated professionals. For example, Davos Man has never been known to object to the ban on foreign doctors practicing in the United States unless they complete a U.S. residency program or the ban on foreign dentists who did not complete a U.S. dental school (or recently a Canadian school). Davos Man is only bothered by protectionist barriers that raise the incomes of autoworkers, textile workers, or other non-college educated workers.

Davos Man is also fine with government regulations that reduce the bargaining power of ordinary workers. For example, Davos Man has not objected to central bank rules that target low inflation even at the cost of raising unemployment. Nor has Davos Man objected to meaningless caps on budget deficits, like those in the European Union, that have kept millions of workers from getting jobs.

Davos Man also strongly supported the bank bailouts in which governments provided trillions of dollars in loans and guarantees to the world’s largest banks in order to protect them from the market. This kept too big to fail banks in business and protected the huge salaries received by their top executives.

In short, Davos Man has no particular interest in a free market or unregulated economic system. They only object to interventions that reduce their income. Of course, Davos Man is happy to have the New York Times and other news outlets describe him as a devotee of the free market, as opposed to simply getting incredibly rich.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Folks looking at the NYT charts comparing the nation’s performance by various measures under President Bush and President Obama may be misled by the health care chart. The chart shows health care spending as a share of GDP rising from 14.0 percent in 2001 to 16.3 percent in 2008, which it describes as the “Bush years.” It shows a further increase to 18.1 percent in 2016, which are the “Obama years.” By this measure we see a modest slowing of health care cost growth as a share of GDP, with a rise of 2.3 percentage points in the Bush years compared with 1.8 percentage points in the Obama years.

The problem here is that the chart puts the end of the Bush years at 2008. Note that the start of the Bush years in 2001, which is of course when he actually took office. If we go out eight years, that puts us at 2009. In that year health care costs were 17.3 percent of GDP. Using this as an endpoint, costs grew by 3.3 percentage points of GDP in the eight years of the Bush administration. They grew by just 0.8 percentage points in the first seven years of the Obama administration. We will need data for 2017 before we can draw the full picture, but we will almost certainly still see a sharp slowing of health care costs under President Obama. Of course, we can argue about the extent to which the Obama administration deserves credit for this slowing of cost growth, but the fact it took place is not disputable.

Folks looking at the NYT charts comparing the nation’s performance by various measures under President Bush and President Obama may be misled by the health care chart. The chart shows health care spending as a share of GDP rising from 14.0 percent in 2001 to 16.3 percent in 2008, which it describes as the “Bush years.” It shows a further increase to 18.1 percent in 2016, which are the “Obama years.” By this measure we see a modest slowing of health care cost growth as a share of GDP, with a rise of 2.3 percentage points in the Bush years compared with 1.8 percentage points in the Obama years.

The problem here is that the chart puts the end of the Bush years at 2008. Note that the start of the Bush years in 2001, which is of course when he actually took office. If we go out eight years, that puts us at 2009. In that year health care costs were 17.3 percent of GDP. Using this as an endpoint, costs grew by 3.3 percentage points of GDP in the eight years of the Bush administration. They grew by just 0.8 percentage points in the first seven years of the Obama administration. We will need data for 2017 before we can draw the full picture, but we will almost certainly still see a sharp slowing of health care costs under President Obama. Of course, we can argue about the extent to which the Obama administration deserves credit for this slowing of cost growth, but the fact it took place is not disputable.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is what the NYT article and the underlying study both concluded. While families on food stamps did spend a somewhat larger share of their food budget on soft drinks and other unhealthy foods, there was not a big difference in their behavior compared with families not receiving food stamps. The headline likely gave readers the opposite impression, telling readers:

“In the shopping cart of a food stamp household: lots of soda.”

Come on folks, try to have your headlines reflect what the article says.

This is what the NYT article and the underlying study both concluded. While families on food stamps did spend a somewhat larger share of their food budget on soft drinks and other unhealthy foods, there was not a big difference in their behavior compared with families not receiving food stamps. The headline likely gave readers the opposite impression, telling readers:

“In the shopping cart of a food stamp household: lots of soda.”

Come on folks, try to have your headlines reflect what the article says.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión