Many of us have been raising the issue that Donald Trump is apparently prepared to defy well-established precedent and continue to maintain his business empire even as he serves as president. For the last fifty years presidents have put their assets in a blind trust so that there would not be a question as to whether they were working to fatten their own pockets or for what they considered the good of the country. This also prevents the most blatant forms of bribery by those seeking to curry the president’s favor.

It is hard to see any reason that Donald Trump should not be held to the same rules. But some have made the argument that, given his extensive holdings, it would be almost impossible to sell them off in the two months remaining until he takes office. This means that he could not avoid the problem of making decisions that will have a direct impact on his business interests.

Actually it is not hard to find a way around this problem:

1) Donald Trump arranges to hire three auditors from an independent accounting firm. Each one does an independent assessment of Trump’s holdings and assigns it a value.

2) The middle assessment becomes a benchmark. Donald Trump buys an insurance policy that will guarantee him that he will get this amount of money when all assets are sold. If the total take is less than the benchmark, he collects on the insurance policy. Any money received in excess of the benchmark goes to a charity of Trump’s choosing (not the Trump Foundation).

3) All the proceeds from the sales are placed in a blind trust.

There you have it, three easy steps that Donald Trump could take if he wanted to end the conflicts of interest he now faces. It doesn’t seem likely that he will go this route on his own, the question is whether anyone (i.e. Republicans) will force him.

Many of us have been raising the issue that Donald Trump is apparently prepared to defy well-established precedent and continue to maintain his business empire even as he serves as president. For the last fifty years presidents have put their assets in a blind trust so that there would not be a question as to whether they were working to fatten their own pockets or for what they considered the good of the country. This also prevents the most blatant forms of bribery by those seeking to curry the president’s favor.

It is hard to see any reason that Donald Trump should not be held to the same rules. But some have made the argument that, given his extensive holdings, it would be almost impossible to sell them off in the two months remaining until he takes office. This means that he could not avoid the problem of making decisions that will have a direct impact on his business interests.

Actually it is not hard to find a way around this problem:

1) Donald Trump arranges to hire three auditors from an independent accounting firm. Each one does an independent assessment of Trump’s holdings and assigns it a value.

2) The middle assessment becomes a benchmark. Donald Trump buys an insurance policy that will guarantee him that he will get this amount of money when all assets are sold. If the total take is less than the benchmark, he collects on the insurance policy. Any money received in excess of the benchmark goes to a charity of Trump’s choosing (not the Trump Foundation).

3) All the proceeds from the sales are placed in a blind trust.

There you have it, three easy steps that Donald Trump could take if he wanted to end the conflicts of interest he now faces. It doesn’t seem likely that he will go this route on his own, the question is whether anyone (i.e. Republicans) will force him.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There are sharp differences between the political parties in many areas, but one principle on which there has been a longstanding agreement is that the presidency should not be used as a marketing platform for the president’s personal business interests. Donald Trump seems determined to break with this principle.

The basic point is simple: when you enter the White House you put your assets into a blind trust. This way when the president makes decisions in various areas of foreign and domestic policy, he or she does not know whether they will personally profit from them. The idea is that we want the president to make decisions based on whether they are good for the country, not whether they will fatten their pocketbook.

Presidents of both parties dating back to Lyndon Johnson followed the practice of putting their assets into a blind trust. Richard Nixon did it, Gerald Ford did it, as did Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. Both President Bushes put their assets into a blind trust. And President Reagan put his assets into a blind trust.

None of these presidents had any problem with the idea that they should not be in a position to know whether their actions were directly helping or hurting them financially. Apparently, Donald Trump thinks he is different.

The potential for conflicts is very real and we are seeing it even now in the transition. Last weekend, Donald Trump met with Shinzo Abe, the prime minister of Japan. His daughter Ivanka sat in on the meeting. Japan is now debating whether to allow casino gambling. This is an area where Trump’s business enterprises could have considerable interest, since he has a stake in many casinos around the world.

Did legalized gambling come up at the meeting? Would Donald Trump be inclined to be more favorable towards Abe if they allowed him to open a casino in Japan? Would he not press an issue because he is worried that Abe could retaliate against his casino business?

The same would apply with every other foreign head of state. For example, Turkey has a president, Recep Erdogan, who is looking increasingly like a dictator. In response to a failed coup last summer, he has arrested a number of opposition leaders and purged universities and even high schools of teachers who are thought to be political opponents.

It turns out that Trump has a stake in a number of resorts in Turkey. Will this affect his attitude toward Erdogan?

These are the sorts of issues that will arise all the time with Trump in the White House. And, there are at least as many on the domestic side involving everything from tax reform to education policy.

Every other president was prepared to put aside their personal business interests when they entered the White House. It is a job requirement; it’s as simple as that. Anyone who cares about the integrity of the U.S. government and that the presidency not be used as a platform for personal enrichment should be demanding that Trump follow longstanding precedent by selling off his holdings and have them placed in a blind trust.

There are sharp differences between the political parties in many areas, but one principle on which there has been a longstanding agreement is that the presidency should not be used as a marketing platform for the president’s personal business interests. Donald Trump seems determined to break with this principle.

The basic point is simple: when you enter the White House you put your assets into a blind trust. This way when the president makes decisions in various areas of foreign and domestic policy, he or she does not know whether they will personally profit from them. The idea is that we want the president to make decisions based on whether they are good for the country, not whether they will fatten their pocketbook.

Presidents of both parties dating back to Lyndon Johnson followed the practice of putting their assets into a blind trust. Richard Nixon did it, Gerald Ford did it, as did Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. Both President Bushes put their assets into a blind trust. And President Reagan put his assets into a blind trust.

None of these presidents had any problem with the idea that they should not be in a position to know whether their actions were directly helping or hurting them financially. Apparently, Donald Trump thinks he is different.

The potential for conflicts is very real and we are seeing it even now in the transition. Last weekend, Donald Trump met with Shinzo Abe, the prime minister of Japan. His daughter Ivanka sat in on the meeting. Japan is now debating whether to allow casino gambling. This is an area where Trump’s business enterprises could have considerable interest, since he has a stake in many casinos around the world.

Did legalized gambling come up at the meeting? Would Donald Trump be inclined to be more favorable towards Abe if they allowed him to open a casino in Japan? Would he not press an issue because he is worried that Abe could retaliate against his casino business?

The same would apply with every other foreign head of state. For example, Turkey has a president, Recep Erdogan, who is looking increasingly like a dictator. In response to a failed coup last summer, he has arrested a number of opposition leaders and purged universities and even high schools of teachers who are thought to be political opponents.

It turns out that Trump has a stake in a number of resorts in Turkey. Will this affect his attitude toward Erdogan?

These are the sorts of issues that will arise all the time with Trump in the White House. And, there are at least as many on the domestic side involving everything from tax reform to education policy.

Every other president was prepared to put aside their personal business interests when they entered the White House. It is a job requirement; it’s as simple as that. Anyone who cares about the integrity of the U.S. government and that the presidency not be used as a platform for personal enrichment should be demanding that Trump follow longstanding precedent by selling off his holdings and have them placed in a blind trust.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a major article warning that a Chinese led trade deal, involving a number of countries in East Asia and the Pacific region, was likely to move forward more quickly with the demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This is reported as being an ominous outcome that should concern readers.

This is the opposite position that economists generally take toward efforts to reduce trade barriers. In most economic models, when some countries reduce their trade barriers and therefore increase economic growth, it also benefits countries who are not party to these trade deals.

This was the reason that the United States generally supported the process through which European countries came together, first in the common market and then in the European Union. The argument was that a more economically prosperous Europe would be a better customer for U.S. products and also a better competitor. In the latter role, Europe would provide economic gains to U.S. consumers as well by offering better and/or lower cost products.

It is interesting that the NYT and other proponents of the TPP are now prepared to turn standard economic logic on its head in order to push this pact. For those without a stake in promoting the TPP, the greater economic integration of the region should be viewed positively.

The NYT ran a major article warning that a Chinese led trade deal, involving a number of countries in East Asia and the Pacific region, was likely to move forward more quickly with the demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This is reported as being an ominous outcome that should concern readers.

This is the opposite position that economists generally take toward efforts to reduce trade barriers. In most economic models, when some countries reduce their trade barriers and therefore increase economic growth, it also benefits countries who are not party to these trade deals.

This was the reason that the United States generally supported the process through which European countries came together, first in the common market and then in the European Union. The argument was that a more economically prosperous Europe would be a better customer for U.S. products and also a better competitor. In the latter role, Europe would provide economic gains to U.S. consumers as well by offering better and/or lower cost products.

It is interesting that the NYT and other proponents of the TPP are now prepared to turn standard economic logic on its head in order to push this pact. For those without a stake in promoting the TPP, the greater economic integration of the region should be viewed positively.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Every economist in the world can quickly explain how a 10 percent tariff on imported steel will lead to corruption. The same logic applies to drug patents, although since they are the equivalent of tariffs many thousand percent (they typically raise the price of protected drugs by factors of ten or even 100 or more), the incentives for corruption are much greater.

This is why every economist in the world should have been nodding their heads saying “I told you so” when they read this NYT article about a kickback scheme between a major drug manufacturer and a mail order pharmacy. Unfortunately, there were no economists mentioned in this piece. And, it is quite possible that most economists support this form of protectionism, in spite of the enormous inefficiency and corruption that results. (Yes this is a major point in my book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

Every economist in the world can quickly explain how a 10 percent tariff on imported steel will lead to corruption. The same logic applies to drug patents, although since they are the equivalent of tariffs many thousand percent (they typically raise the price of protected drugs by factors of ten or even 100 or more), the incentives for corruption are much greater.

This is why every economist in the world should have been nodding their heads saying “I told you so” when they read this NYT article about a kickback scheme between a major drug manufacturer and a mail order pharmacy. Unfortunately, there were no economists mentioned in this piece. And, it is quite possible that most economists support this form of protectionism, in spite of the enormous inefficiency and corruption that results. (Yes this is a major point in my book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Hedge fund manager and Trump transition team member Anthony Scaramucci, repeated one of the great lies of the era of Trump on Morning Edition today. He claimed that businesses could not get access to credit and blamed it on the regulations in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill. This is the reason that he and others have given for repealing Dodd-Frank.

The problem with this story is that it is entirely an invention of the right wing. As I point out earlier this week the National Federation of Independent Businesses has been conducting a monthly survey of small businesses for more than thirty years. One of questions it poses is about credit conditions. In the most recent survey only 2 percent reported that financing was their top business problem. This is near a low point for the survey’s history. In other words, they are finding that small businesses are having very little problem getting access to credit.

Larger businesses that can borrow directly through credit markets also have little problem. Many economists, including Fed Chair Janet Yellen, have worried about the collapse of credit spreads, meaning that they are concerned that risky businesses actually are getting credit at too low an interest rate.

In other words, the idea that Dodd-Frank is preventing businesses from getting credit is a complete invention, like Fox’s War on Christmas.

Hedge fund manager and Trump transition team member Anthony Scaramucci, repeated one of the great lies of the era of Trump on Morning Edition today. He claimed that businesses could not get access to credit and blamed it on the regulations in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill. This is the reason that he and others have given for repealing Dodd-Frank.

The problem with this story is that it is entirely an invention of the right wing. As I point out earlier this week the National Federation of Independent Businesses has been conducting a monthly survey of small businesses for more than thirty years. One of questions it poses is about credit conditions. In the most recent survey only 2 percent reported that financing was their top business problem. This is near a low point for the survey’s history. In other words, they are finding that small businesses are having very little problem getting access to credit.

Larger businesses that can borrow directly through credit markets also have little problem. Many economists, including Fed Chair Janet Yellen, have worried about the collapse of credit spreads, meaning that they are concerned that risky businesses actually are getting credit at too low an interest rate.

In other words, the idea that Dodd-Frank is preventing businesses from getting credit is a complete invention, like Fox’s War on Christmas.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Sebastian Mallaby use his Washington Post column to warn readers that the fiscal stimulus from a Trump administration, in the form of stimulus spending and tax cuts, could lead to too much demand in the economy. The result will be higher interest rates and higher inflation. And then things might get really bad:

“The economy would spiral back toward the stagflationary 1970s. It is too dark a prospect to believe. But the logic that takes us from here to there is chillingly straightforward.”

Woooooooo, “chillingly straightforward?”

Okay, some of us are old enough to remember the seventies and they were not exactly the horror story that Mallaby paints. Employment grew by more than 27 percent over the course of the decade. This translates into an annual growth rate of almost 2.5 percent, which would come to more than 3.2 million new jobs a year. Are you scared yet?

GDP grew at an annual rate of almost 3.2 percent. That looks pretty good compared to the 2.0 percent rate we have been seeing the last six years.

Of course, the seventies were not all great. There was a sharp slowdown in productivity growth that began in 1973. This led to stagnating wages for the rest of the decade. It is worth noting that, in contrast to later decades, the wage stagnation of the 1970s was due to weak productivity growth, not upward redistribution.

It is also worth pointing out that there were unique events that pushed inflation higher in the 1970s, most importantly the quadrupling of world oil prices in 1973–74 and then again in 1978–1979 following the Iranian revolution. Also, there was a measurement error in the consumer price index that had the effect of amplifying rises in the inflation rate at a time when wage and other contracts were widely indexed.

Anyhow, the key point here is that the horror story of the seventies, which is often told by Mallaby and others, is their own invention, not something that existed in the real world. This is important in the context of Trump’s economic proposals, since they actually could provide a considerable boost to demand and employment.

It is certainly possible that his tax cuts go too far in creating large deficits, which could mean higher interest rates and higher inflation, as Mallaby suggests. But it is absurd to claim that economic disaster, in the form of runaway inflation, is just around the corner.

There are many very good reasons to fear a Donald Trump administration, but the risk that he might over-stimulate the economy is not one of them.

Sebastian Mallaby use his Washington Post column to warn readers that the fiscal stimulus from a Trump administration, in the form of stimulus spending and tax cuts, could lead to too much demand in the economy. The result will be higher interest rates and higher inflation. And then things might get really bad:

“The economy would spiral back toward the stagflationary 1970s. It is too dark a prospect to believe. But the logic that takes us from here to there is chillingly straightforward.”

Woooooooo, “chillingly straightforward?”

Okay, some of us are old enough to remember the seventies and they were not exactly the horror story that Mallaby paints. Employment grew by more than 27 percent over the course of the decade. This translates into an annual growth rate of almost 2.5 percent, which would come to more than 3.2 million new jobs a year. Are you scared yet?

GDP grew at an annual rate of almost 3.2 percent. That looks pretty good compared to the 2.0 percent rate we have been seeing the last six years.

Of course, the seventies were not all great. There was a sharp slowdown in productivity growth that began in 1973. This led to stagnating wages for the rest of the decade. It is worth noting that, in contrast to later decades, the wage stagnation of the 1970s was due to weak productivity growth, not upward redistribution.

It is also worth pointing out that there were unique events that pushed inflation higher in the 1970s, most importantly the quadrupling of world oil prices in 1973–74 and then again in 1978–1979 following the Iranian revolution. Also, there was a measurement error in the consumer price index that had the effect of amplifying rises in the inflation rate at a time when wage and other contracts were widely indexed.

Anyhow, the key point here is that the horror story of the seventies, which is often told by Mallaby and others, is their own invention, not something that existed in the real world. This is important in the context of Trump’s economic proposals, since they actually could provide a considerable boost to demand and employment.

It is certainly possible that his tax cuts go too far in creating large deficits, which could mean higher interest rates and higher inflation, as Mallaby suggests. But it is absurd to claim that economic disaster, in the form of runaway inflation, is just around the corner.

There are many very good reasons to fear a Donald Trump administration, but the risk that he might over-stimulate the economy is not one of them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT bizarrely equated trade with trade agreements in an article on a debate within the Democratic Party over its future policy course. The piece referred to Senator Bernie Sanders’ opposition to recent trade pacts then presented a quote from Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper:

“I don’t think you can be anti-trade…In the modern world, we need consumers overseas for our products as well.”

Of course Sanders has never indicated he was against trade, nor has any prominent figure in this debate, so as presented, Mr. Hickenlooper’s comment is essentially a non sequitur. In fact, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the trade deal most in the news at present, actually contains major protectionist measures in the form of stronger and longer patent and copyright related protections, arguably it is supporters of this pact who can most accurately be called “anti-trade.”

Anyhow, if Mr, Hickenlooper is effectively speaking in non sequiturs it would be appropriate to call attention to this fact. After all he is identified in the piece as being “mentioned as a possible 2020 presidential candidate.”

The NYT bizarrely equated trade with trade agreements in an article on a debate within the Democratic Party over its future policy course. The piece referred to Senator Bernie Sanders’ opposition to recent trade pacts then presented a quote from Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper:

“I don’t think you can be anti-trade…In the modern world, we need consumers overseas for our products as well.”

Of course Sanders has never indicated he was against trade, nor has any prominent figure in this debate, so as presented, Mr. Hickenlooper’s comment is essentially a non sequitur. In fact, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the trade deal most in the news at present, actually contains major protectionist measures in the form of stronger and longer patent and copyright related protections, arguably it is supporters of this pact who can most accurately be called “anti-trade.”

Anyhow, if Mr, Hickenlooper is effectively speaking in non sequiturs it would be appropriate to call attention to this fact. After all he is identified in the piece as being “mentioned as a possible 2020 presidential candidate.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Lara Merling and Dean Baker

For the second time in the last five elections we are seeing a situation where the candidate who came in second in the popular vote ends up in the White House. This is of course due to the Electoral College.

As just about everyone knows, the Electoral College can lead to this result since it follows a winner take all rule (with the exception of Nebraska and Maine). A candidate gets all the electoral votes of a state whether they win it by one vote or one million. In this election, Secretary Clinton ran up huge majorities in California and New York, but her large margins meant nothing in the Electoral College.

In addition to the problem of this winner take all logic, there is also the issue that people in large states are explicitly underrepresented in the Electoral College. While votes are roughly proportionately distributed, since even the smallest states are guaranteed three votes, the people in these states end up being over-represented in the Electoral College. For example, in Wyoming, there is an electoral vote for every 195,000 residents, in North Dakota there is one for every 252,000, and in Rhode Island one for every 264,000. On the other hand, in California there is an electoral vote for every 711,000 residents, in Florida one for every 699,000, and in Texas one for every 723,000.

The states that are overrepresented in the Electoral College also happen to be less diverse than the country as a whole. Wyoming is 84 percent white, North Dakota is 86 percent white, and Rhode Island is 74 percent white, while in California only 38 percent of the population is white, in Florida 55 percent, and in Texas 43 percent. White people tend to live in states where their vote counts more, and minorities in places where it counts less. This means that the Electoral College not only can produce results that conflict with a majority vote, but it is biased in a way that amplifies the votes of white people and reduces the voice of minorities.

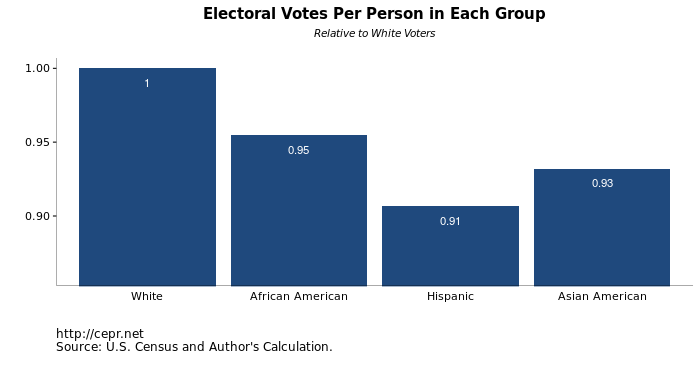

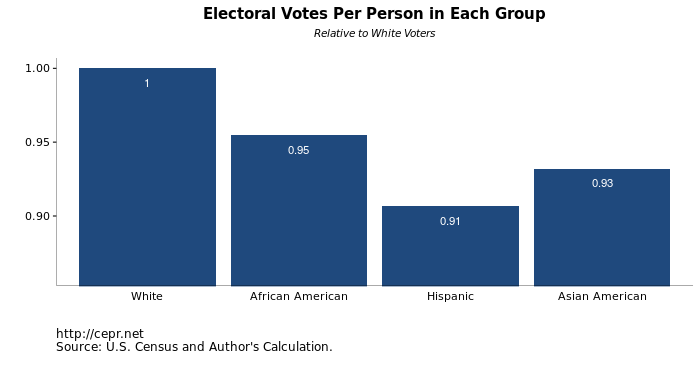

The figure illustrates the gap in Electoral College representation for minority voters. Based on the weight of each vote in each state and given the fact that most minority voters reside in states where each person’s vote counts less in the Electoral College, the result is minority voters are grossly underrepresented. African American votes on average have a weight that is 95 percent as much as white votes, Hispanic votes are on average 91 percent, and Asian American votes, 93 percent as much of a white vote. In the Electoral College, white votes matter more.

Addendum

It is worth noting that there is a fix to this problem which does not require a constitutional amendment or even action by Congress. The organization, National Popular Vote, has been pushing states to pass legislation whereby their electoral votes will go to the winner of the national popular vote. This switch does not happen until states representing a majority of electoral votes have passed the same legislation. At that point, the winner of the popular vote will automatically be the winner of the electoral vote.

Lara Merling and Dean Baker

For the second time in the last five elections we are seeing a situation where the candidate who came in second in the popular vote ends up in the White House. This is of course due to the Electoral College.

As just about everyone knows, the Electoral College can lead to this result since it follows a winner take all rule (with the exception of Nebraska and Maine). A candidate gets all the electoral votes of a state whether they win it by one vote or one million. In this election, Secretary Clinton ran up huge majorities in California and New York, but her large margins meant nothing in the Electoral College.

In addition to the problem of this winner take all logic, there is also the issue that people in large states are explicitly underrepresented in the Electoral College. While votes are roughly proportionately distributed, since even the smallest states are guaranteed three votes, the people in these states end up being over-represented in the Electoral College. For example, in Wyoming, there is an electoral vote for every 195,000 residents, in North Dakota there is one for every 252,000, and in Rhode Island one for every 264,000. On the other hand, in California there is an electoral vote for every 711,000 residents, in Florida one for every 699,000, and in Texas one for every 723,000.

The states that are overrepresented in the Electoral College also happen to be less diverse than the country as a whole. Wyoming is 84 percent white, North Dakota is 86 percent white, and Rhode Island is 74 percent white, while in California only 38 percent of the population is white, in Florida 55 percent, and in Texas 43 percent. White people tend to live in states where their vote counts more, and minorities in places where it counts less. This means that the Electoral College not only can produce results that conflict with a majority vote, but it is biased in a way that amplifies the votes of white people and reduces the voice of minorities.

The figure illustrates the gap in Electoral College representation for minority voters. Based on the weight of each vote in each state and given the fact that most minority voters reside in states where each person’s vote counts less in the Electoral College, the result is minority voters are grossly underrepresented. African American votes on average have a weight that is 95 percent as much as white votes, Hispanic votes are on average 91 percent, and Asian American votes, 93 percent as much of a white vote. In the Electoral College, white votes matter more.

Addendum

It is worth noting that there is a fix to this problem which does not require a constitutional amendment or even action by Congress. The organization, National Popular Vote, has been pushing states to pass legislation whereby their electoral votes will go to the winner of the national popular vote. This switch does not happen until states representing a majority of electoral votes have passed the same legislation. At that point, the winner of the popular vote will automatically be the winner of the electoral vote.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión