Thomas Edsall’s NYT column contrasted the downscale white working class Trump supporters with the growing number of college educated and relatively upscale supporters of Democrats. Near the end of the piece, Edsall quotes M.I.T. economist Daron Acemoglu:

“As long as the Democratic Party shakes off its hard-core anti-market, pro-union stance, there is a huge constituency of well-educated, socially conscious Americans that will join in.”

Rather than completely abandon its base in the working class (of all races) there is an alternative route for the Democrats, they could abandon their hard core anti-market positions that benefit the wealthy.

This could start with abandoning their position, especially in trade deals, to make government granted patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. These anti-market interventions are affecting an ever larger share of the economy (in prescription drugs alone patent related protections likely increase the costs by more than $350 billion annually). They directly redistribute income from ordinary workers to the relatively wealthy minority in a position to earn rents from these forms of protectionism.

The Democrats can also abandon the licensing restrictions that protect doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals from both domestic and international competition. Our laws prevent doctors from practicing medicine unless they complete a U.S. residency program. This is about as blatant a protectionist barrier as you’ll find these days. It allows doctors in the United States to earn on average more than $250,000 a year, twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries like Germany and Canada. This protectionism costs us around $100 billion a year in higher medical costs.

We could also subject the financial sector to the same sort of taxes as other sectors of the economy pay (e.g. a financial transactions tax). This market based reform could eliminate more than $100 billion a year in waste in the financial sector that ends up as income for bankers and hedge fund types.

There is a long list of market-friendly measures that would help to reverse the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yep, this is the topic of my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.) Anyhow, supporters of this upward redistribution do their best to turn language on its head and deny that these forms of protectionism are protection. They pretend that patent and copyright protections are the free market or that they never heard of restrictions on foreign doctors. Unfortunately, this group of deniers includes most of the people who write on these issues. But, there is always hope that they can learn.

Note: Typos in an earlier version were corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Thomas Edsall’s NYT column contrasted the downscale white working class Trump supporters with the growing number of college educated and relatively upscale supporters of Democrats. Near the end of the piece, Edsall quotes M.I.T. economist Daron Acemoglu:

“As long as the Democratic Party shakes off its hard-core anti-market, pro-union stance, there is a huge constituency of well-educated, socially conscious Americans that will join in.”

Rather than completely abandon its base in the working class (of all races) there is an alternative route for the Democrats, they could abandon their hard core anti-market positions that benefit the wealthy.

This could start with abandoning their position, especially in trade deals, to make government granted patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. These anti-market interventions are affecting an ever larger share of the economy (in prescription drugs alone patent related protections likely increase the costs by more than $350 billion annually). They directly redistribute income from ordinary workers to the relatively wealthy minority in a position to earn rents from these forms of protectionism.

The Democrats can also abandon the licensing restrictions that protect doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals from both domestic and international competition. Our laws prevent doctors from practicing medicine unless they complete a U.S. residency program. This is about as blatant a protectionist barrier as you’ll find these days. It allows doctors in the United States to earn on average more than $250,000 a year, twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries like Germany and Canada. This protectionism costs us around $100 billion a year in higher medical costs.

We could also subject the financial sector to the same sort of taxes as other sectors of the economy pay (e.g. a financial transactions tax). This market based reform could eliminate more than $100 billion a year in waste in the financial sector that ends up as income for bankers and hedge fund types.

There is a long list of market-friendly measures that would help to reverse the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yep, this is the topic of my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.) Anyhow, supporters of this upward redistribution do their best to turn language on its head and deny that these forms of protectionism are protection. They pretend that patent and copyright protections are the free market or that they never heard of restrictions on foreign doctors. Unfortunately, this group of deniers includes most of the people who write on these issues. But, there is always hope that they can learn.

Note: Typos in an earlier version were corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

by Dean Baker and Lara Merling

It’s no secret that many folks, including many on the Fed, want to see higher interest rates. There are a variety of arguments put forward, including the story of huge but invisible bubbles that could burst and sink the economy just like the housing bubble did in 2008.

But the argument that deserves the most credibility is the conventional one that a low rate of unemployment is creating an overtight labor market. This leads to more wage growth, which will get passed along in more rapid inflation, which will soon force the Fed’s hand. At some point the Fed will have to raise rates to keep inflation from getting out of control or we will be back in an era of excessive inflation. By this logic it is better to get out front and do it now.

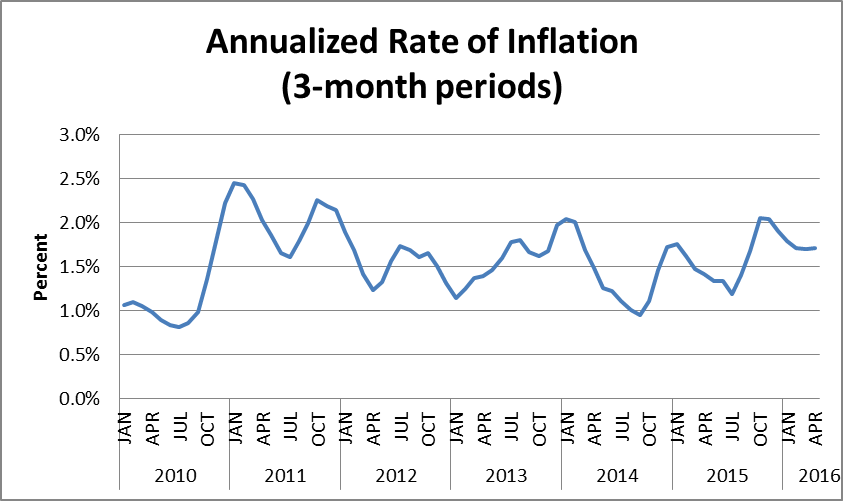

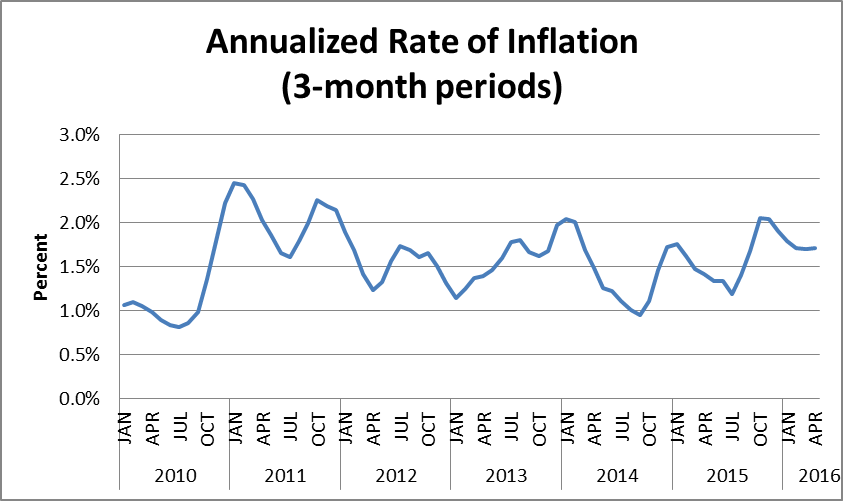

In this story, we should at least be seeing the beginnings of an acceleration of inflation, but we don’t. The figure below shows the core personal consumption expenditure deflator which provides the basis for the Fed’s 2.0 percent (average) inflation target.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The figure shows the annualized rate of inflation using average price levels from the most recent three-month period compared with average price levels from the prior three month period. It’s pretty hard to see any evidence of an upward trend in these data. The core rate had approached 2.5 percent in early 2011. It had minor fluctuations, but eventually bottomed out at 1.0 percent in the fall of 2014. It has moved modestly higher in the last two years, peaking at 2.0 percent at the end of 2015, but since then has crept down to 1.7 percent.

Of course, it is always possible that we will see the picture change and inflation will suddenly start to accelerate, but the point is that it has not yet done so. Furthermore, none of the standard models show that inflation suddenly jumps upward. If it does start to increase it would likely be a long and gradual process. For this reason, it is difficult to see the urgency in the drive to raise interest rates.

by Dean Baker and Lara Merling

It’s no secret that many folks, including many on the Fed, want to see higher interest rates. There are a variety of arguments put forward, including the story of huge but invisible bubbles that could burst and sink the economy just like the housing bubble did in 2008.

But the argument that deserves the most credibility is the conventional one that a low rate of unemployment is creating an overtight labor market. This leads to more wage growth, which will get passed along in more rapid inflation, which will soon force the Fed’s hand. At some point the Fed will have to raise rates to keep inflation from getting out of control or we will be back in an era of excessive inflation. By this logic it is better to get out front and do it now.

In this story, we should at least be seeing the beginnings of an acceleration of inflation, but we don’t. The figure below shows the core personal consumption expenditure deflator which provides the basis for the Fed’s 2.0 percent (average) inflation target.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The figure shows the annualized rate of inflation using average price levels from the most recent three-month period compared with average price levels from the prior three month period. It’s pretty hard to see any evidence of an upward trend in these data. The core rate had approached 2.5 percent in early 2011. It had minor fluctuations, but eventually bottomed out at 1.0 percent in the fall of 2014. It has moved modestly higher in the last two years, peaking at 2.0 percent at the end of 2015, but since then has crept down to 1.7 percent.

Of course, it is always possible that we will see the picture change and inflation will suddenly start to accelerate, but the point is that it has not yet done so. Furthermore, none of the standard models show that inflation suddenly jumps upward. If it does start to increase it would likely be a long and gradual process. For this reason, it is difficult to see the urgency in the drive to raise interest rates.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting article arguing that trade has stopped growing in the last couple of years. The piece notes data showing that combined U.S. exports and imports fell in the 2015 compared to 2014 and seem likely to fall again in 2016. It then raises the concern that this will lead to slower growth going forward. There are a couple of points that complicate this issue.

The first is that the drop in the dollar value of trade is the result of lower prices, not a smaller volume of goods and services being imported and exported. While the nominal value of exports fell by $111.0 billion from 2014 to 2015, the real value actually rose by $2.3 billion. On the import side, the nominal value fell by $97.8 billion while the real value rose by $116.5 billion.

In other words, the actual amount of goods and services crossing U.S. borders in 2015 was in fact higher in 2015 than in 2014, we were just paying less for what we imported and foreigners were paying less for what we exported to them. The big factors here were the sharp drop in oil prices and comparable drops in the price of many agricultural commodities that we export. It is not clear that this is bad for economic growth, but in any case the issue is not a drop in the quantity of goods and services crossing national borders.

The other point is that the definition of a traded item can change depending on the property rules in place at the time. To take a simple example, suppose that one billion people in China use Microsoft’s Windows operating system. If we make them all pay $50 for each system then this is $50 billion in U.S. exports to China. Now suppose that everyone in China is able to use Windows at no cost. In this case we have $50 billion less in exports, but we still have one billion people in China getting the benefit of the Windows operating system.

Much of the focus of U.S. trade policy in recent decades has been about making other countries pay for items that in principle could be free through patents and copyright protection. (Yes, this is protectionism, even if your friends profit from it.) It is not clear that we are boosting world growth by making countries pay more money for items like prescription drugs, software, recorded music and video material, although we would certainly be increasing the dollar value of trade flows.

The long and short is that it is not clear what we are measuring when we see a decline in trading or volume or what it would mean if trading volume increases because we can force other countries to pay for items that would otherwise be available for free. (Yes, these issues are covered in my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, which is available for free.)

The NYT had an interesting article arguing that trade has stopped growing in the last couple of years. The piece notes data showing that combined U.S. exports and imports fell in the 2015 compared to 2014 and seem likely to fall again in 2016. It then raises the concern that this will lead to slower growth going forward. There are a couple of points that complicate this issue.

The first is that the drop in the dollar value of trade is the result of lower prices, not a smaller volume of goods and services being imported and exported. While the nominal value of exports fell by $111.0 billion from 2014 to 2015, the real value actually rose by $2.3 billion. On the import side, the nominal value fell by $97.8 billion while the real value rose by $116.5 billion.

In other words, the actual amount of goods and services crossing U.S. borders in 2015 was in fact higher in 2015 than in 2014, we were just paying less for what we imported and foreigners were paying less for what we exported to them. The big factors here were the sharp drop in oil prices and comparable drops in the price of many agricultural commodities that we export. It is not clear that this is bad for economic growth, but in any case the issue is not a drop in the quantity of goods and services crossing national borders.

The other point is that the definition of a traded item can change depending on the property rules in place at the time. To take a simple example, suppose that one billion people in China use Microsoft’s Windows operating system. If we make them all pay $50 for each system then this is $50 billion in U.S. exports to China. Now suppose that everyone in China is able to use Windows at no cost. In this case we have $50 billion less in exports, but we still have one billion people in China getting the benefit of the Windows operating system.

Much of the focus of U.S. trade policy in recent decades has been about making other countries pay for items that in principle could be free through patents and copyright protection. (Yes, this is protectionism, even if your friends profit from it.) It is not clear that we are boosting world growth by making countries pay more money for items like prescription drugs, software, recorded music and video material, although we would certainly be increasing the dollar value of trade flows.

The long and short is that it is not clear what we are measuring when we see a decline in trading or volume or what it would mean if trading volume increases because we can force other countries to pay for items that would otherwise be available for free. (Yes, these issues are covered in my new book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, which is available for free.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

By Lara Merling

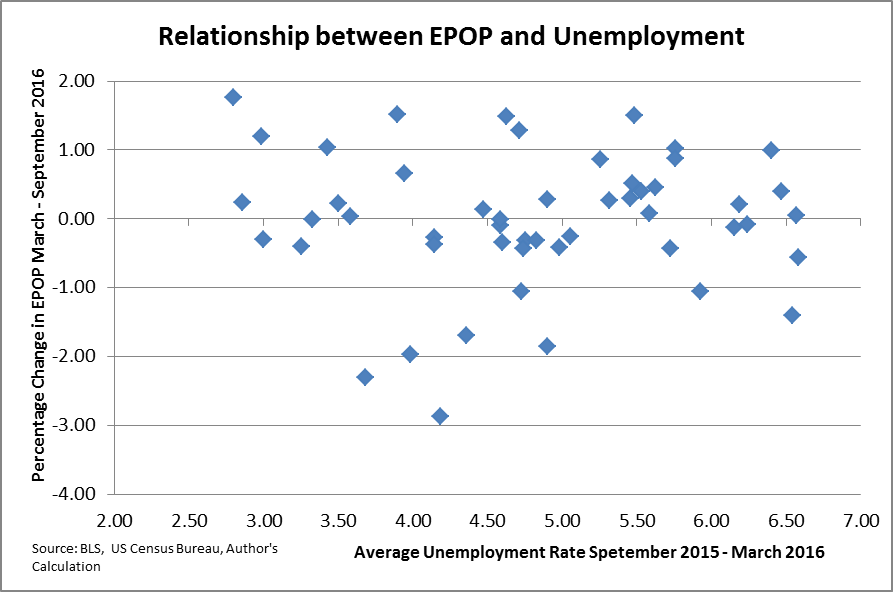

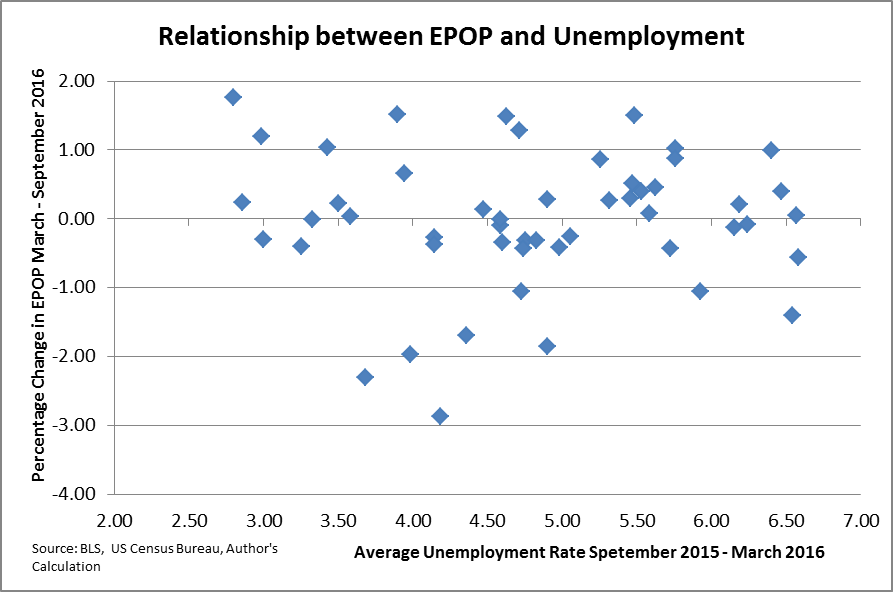

The official unemployment rate in the U.S. is currently estimated at 5 percent, a number that is sufficiently low for some to claim that the economy is at full employment. The unemployment rate varies significantly across states. Between September 2015 and March 2016 the unemployment rate has averaged 2.8 percent in North Dakota, 3 percent in Hawaii and New Hampshire, while in West Virginia it was at 6.4 percent, and in Washington DC, and Alaska it averaged 6.6 percent.

Once the labor market is at full employment, it is difficult to have much by way of further employment gains beyond the growth in the working-age population. If the current 5.0 percent unemployment rate is actually close to full employment, then we should expect to see smaller increases in the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) in states with lower unemployment rates, since these states should be running up against the full employment limit. We would then expect higher gains in EPOPs in states that have higher unemployment rates which are further away from reaching full employment.

The figure below compares the change in the EPOP in each state over the period from March 2016 and September 2016, for people between the ages of 18 and 64, with the state’s average unemployment rate for September 2015 to March 2016.

As can be seen there is no relationship between the unemployment level and the change in EPOP. Some states with very low unemployment rates have seen large increases in EPOP, while some of the states with the highest unemployment levels have seen much smaller increases, or even decreases in EPOP. While this comparison is far from conclusive, it does not easily fit with a story with the labor market approaching full employment.

By Lara Merling

The official unemployment rate in the U.S. is currently estimated at 5 percent, a number that is sufficiently low for some to claim that the economy is at full employment. The unemployment rate varies significantly across states. Between September 2015 and March 2016 the unemployment rate has averaged 2.8 percent in North Dakota, 3 percent in Hawaii and New Hampshire, while in West Virginia it was at 6.4 percent, and in Washington DC, and Alaska it averaged 6.6 percent.

Once the labor market is at full employment, it is difficult to have much by way of further employment gains beyond the growth in the working-age population. If the current 5.0 percent unemployment rate is actually close to full employment, then we should expect to see smaller increases in the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) in states with lower unemployment rates, since these states should be running up against the full employment limit. We would then expect higher gains in EPOPs in states that have higher unemployment rates which are further away from reaching full employment.

The figure below compares the change in the EPOP in each state over the period from March 2016 and September 2016, for people between the ages of 18 and 64, with the state’s average unemployment rate for September 2015 to March 2016.

As can be seen there is no relationship between the unemployment level and the change in EPOP. Some states with very low unemployment rates have seen large increases in EPOP, while some of the states with the highest unemployment levels have seen much smaller increases, or even decreases in EPOP. While this comparison is far from conclusive, it does not easily fit with a story with the labor market approaching full employment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Washington Post article told readers that the 2.9 percent GDP growth reported for the third quarter made it more likely the Fed would raise interest rates at its December meeting. Part of its story is that inflation is accelerating.

“Inflation remains below the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent but is creeping closer to that level.”

Actually, the opposite is the case. The report (Appendix Table A) showed that the core personal consumption expenditure deflator increased at a 1.7 percent annual rate in the third quarter. That is down from 2.1 percent in the first quarter and 1.8 percent in the second quarter.

A Washington Post article told readers that the 2.9 percent GDP growth reported for the third quarter made it more likely the Fed would raise interest rates at its December meeting. Part of its story is that inflation is accelerating.

“Inflation remains below the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent but is creeping closer to that level.”

Actually, the opposite is the case. The report (Appendix Table A) showed that the core personal consumption expenditure deflator increased at a 1.7 percent annual rate in the third quarter. That is down from 2.1 percent in the first quarter and 1.8 percent in the second quarter.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The coverage of the new law in New York state, which would prohibit the short-term renting of whole apartments in New York City, has been difficult to understand. It presents as competing claims that it would increase the supply of affordable housing in New York City and that it will allow hotels to raise their fees. (This Washington Post piece is an excellent example.) Actually, it will likely do both.

The basic story is that the city has a large number of units that are subject to some form of rent control. The purpose is to keep these units affordable for people who don’t work on Wall Street. This purpose is defeated if it is possible for either the landlord or tenant to rent out the unit through a service like Airbnb. If the landord is going the Airbnb route then it removes a unit of otherwise affordable housing from the market. If the tenant is going the Airbnb route then they are taking advantage of rent control to make a profit on arbitrage.

This is also bad news for the hotel industry, since people who might have otherwise stayed in hotels will instead stay in Airbnb units, thereby lowering occupancy rates and putting downward pressure on hotel prices. Therefore, there is absolutely nothing contradictory about the argument this measure will both increase the supply of affordable housing and benefit the hotel industry.

The long-run story may be somewhat different. In the long-run the construction of hotels is responsive to demand. If there is a high vacancy rate in the city’s hotels, there will be fewer hotels built in future years. This will leave more land for the construction of apartments and other uses. In that case, the restriction on Airbnb rentals may not ultimately lead to an increase in the number of affordable housing units in the city (a financial transactions tax would be more effective), but is perfectly reasonable to believe that in the short-term this restriction on Airbnb rentals will both increase the supply of affordable housing units and benefit the hotel industry.

The coverage of the new law in New York state, which would prohibit the short-term renting of whole apartments in New York City, has been difficult to understand. It presents as competing claims that it would increase the supply of affordable housing in New York City and that it will allow hotels to raise their fees. (This Washington Post piece is an excellent example.) Actually, it will likely do both.

The basic story is that the city has a large number of units that are subject to some form of rent control. The purpose is to keep these units affordable for people who don’t work on Wall Street. This purpose is defeated if it is possible for either the landlord or tenant to rent out the unit through a service like Airbnb. If the landord is going the Airbnb route then it removes a unit of otherwise affordable housing from the market. If the tenant is going the Airbnb route then they are taking advantage of rent control to make a profit on arbitrage.

This is also bad news for the hotel industry, since people who might have otherwise stayed in hotels will instead stay in Airbnb units, thereby lowering occupancy rates and putting downward pressure on hotel prices. Therefore, there is absolutely nothing contradictory about the argument this measure will both increase the supply of affordable housing and benefit the hotel industry.

The long-run story may be somewhat different. In the long-run the construction of hotels is responsive to demand. If there is a high vacancy rate in the city’s hotels, there will be fewer hotels built in future years. This will leave more land for the construction of apartments and other uses. In that case, the restriction on Airbnb rentals may not ultimately lead to an increase in the number of affordable housing units in the city (a financial transactions tax would be more effective), but is perfectly reasonable to believe that in the short-term this restriction on Airbnb rentals will both increase the supply of affordable housing units and benefit the hotel industry.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a major adventure in fantasy land when it ran a front page article asserting that the problem with the health care exchanges under the Affordable Care Act is that the penalties have not been large enough to coerce people into getting health care insurance. The begins by telling readers:

“The architects of the Affordable Care Act thought they had a blunt instrument to force people — even young and healthy ones — to buy insurance through the law’s online marketplaces: a tax penalty for those who remain uninsured.

“It has not worked all that well, and that is at least partly to blame for soaring premiums next year on some of the health law’s insurance exchanges.”

The piece then explains that many people are opting not to buy insurance and instead pay the penalty.

The problem with this line of argument for fans of reality is that the number of uninsured has actually fallen by more than had been projected at the time the law was passed. This is in spite of the fact that many states were allowed to opt out of the Medicare expansion by a 2012 Supreme Court decision making expansion optional. (It was mandatory in the law passed by Congress.)

It is not difficult to find the evidence that the number of uninsured has fallen more than projected. In March of 2012, the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Tax Committee projected that there would be 32 million uninsured non-elderly people in 2015. Estimates from the Kaiser Family Foundation put the actual number at just under 29 million. In other words, three million more people were getting insured as of last year (our most recent data) than had been projected before most of the ACA took effect.

So, if more people are getting insured than had been expected, how could the penalties have been a failure? I leave that one for the folks at the NYT responsible for this front page story.

I will add one other item in this story worth correcting. The piece includes a quote from Joseph J. Thorndike, the director of the tax history project at Tax Analysts, telling readers:

“If it [the mandate] were effective, we would have higher enrollment, and the population buying policies in the insurance exchange would be healthier and younger.”

While we do care whether the people in the exchanges are healthy, it doesn’t matter if they are young. In fact, healthy older people are far more profitable to insurers than healthy young people since their premiums are on average three times as high. There is a slight skewing against the young in the structure of premiums, but this has little consequence for the costs of the system.

As a practical matter, the people signing up on the exchanges are probably somewhat less healthy than had been expected, but this is largely because more people are getting insurance through employers than had been expected. The people who get insurance through their employers are more healthy than the population as a whole, since for the most part they are healthy enough to be working full-time jobs.

The New York Times had a major adventure in fantasy land when it ran a front page article asserting that the problem with the health care exchanges under the Affordable Care Act is that the penalties have not been large enough to coerce people into getting health care insurance. The begins by telling readers:

“The architects of the Affordable Care Act thought they had a blunt instrument to force people — even young and healthy ones — to buy insurance through the law’s online marketplaces: a tax penalty for those who remain uninsured.

“It has not worked all that well, and that is at least partly to blame for soaring premiums next year on some of the health law’s insurance exchanges.”

The piece then explains that many people are opting not to buy insurance and instead pay the penalty.

The problem with this line of argument for fans of reality is that the number of uninsured has actually fallen by more than had been projected at the time the law was passed. This is in spite of the fact that many states were allowed to opt out of the Medicare expansion by a 2012 Supreme Court decision making expansion optional. (It was mandatory in the law passed by Congress.)

It is not difficult to find the evidence that the number of uninsured has fallen more than projected. In March of 2012, the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Tax Committee projected that there would be 32 million uninsured non-elderly people in 2015. Estimates from the Kaiser Family Foundation put the actual number at just under 29 million. In other words, three million more people were getting insured as of last year (our most recent data) than had been projected before most of the ACA took effect.

So, if more people are getting insured than had been expected, how could the penalties have been a failure? I leave that one for the folks at the NYT responsible for this front page story.

I will add one other item in this story worth correcting. The piece includes a quote from Joseph J. Thorndike, the director of the tax history project at Tax Analysts, telling readers:

“If it [the mandate] were effective, we would have higher enrollment, and the population buying policies in the insurance exchange would be healthier and younger.”

While we do care whether the people in the exchanges are healthy, it doesn’t matter if they are young. In fact, healthy older people are far more profitable to insurers than healthy young people since their premiums are on average three times as high. There is a slight skewing against the young in the structure of premiums, but this has little consequence for the costs of the system.

As a practical matter, the people signing up on the exchanges are probably somewhat less healthy than had been expected, but this is largely because more people are getting insurance through employers than had been expected. The people who get insurance through their employers are more healthy than the population as a whole, since for the most part they are healthy enough to be working full-time jobs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión