Thomas Friedman once again urged both major parties to compromise to get things done in his NYT column. He argues that compromise is the only way to get things done. To make his case he lists a number of issues where he argues compromise is necessary, leading with:

“How will we improve Obamacare?”

Friedman probably missed it (hard to get information about Washington politics at The New York Times), but the Republicans have made repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) a sacred cause. They routinely demand the destruction of the ACA in their campaigns. They voted dozens of times to repeal the ACA and have celebrated any bad news that could be associated with the program. This is in addition to all the phony stories about the ACA killing jobs and forcing employers to switch to part-time workers that the Republicans have invented.

In this context, at this point doing anything to further Obamacare would amount to complete surrender on core Republican principles, not a compromise. But you would have to know something about Washington politics to be aware of this fact.

Thomas Friedman once again urged both major parties to compromise to get things done in his NYT column. He argues that compromise is the only way to get things done. To make his case he lists a number of issues where he argues compromise is necessary, leading with:

“How will we improve Obamacare?”

Friedman probably missed it (hard to get information about Washington politics at The New York Times), but the Republicans have made repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) a sacred cause. They routinely demand the destruction of the ACA in their campaigns. They voted dozens of times to repeal the ACA and have celebrated any bad news that could be associated with the program. This is in addition to all the phony stories about the ACA killing jobs and forcing employers to switch to part-time workers that the Republicans have invented.

In this context, at this point doing anything to further Obamacare would amount to complete surrender on core Republican principles, not a compromise. But you would have to know something about Washington politics to be aware of this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what they warned, but they didn’t quite put it to readers that way. Instead the subhead warned that meeting President Obama’s goal of reducing emissions by 80 percent by 2050 would cost $5.28 trillion.

Yes folks, that sounds pretty scary. After all, $5.28 trillion over the next 34 years is bigger than a bread box, possibly much bigger.

Of course, it is unlikely that many of the WSJ’s readers have a clear idea of how big the economy will be over this 34-year period, so they are not likely to be in a good position to assess how much of a burden this would be. Since annual output will average more than $20 trillion a year (in 2016 dollars), this sum comes to about 0.9 percent of projected GDP. (This context is included near the bottom of the piece.) By comparison, the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars at their peak was roughly 2.0 percent of GDP, implying that they imposed more than twice the burden on the economy as President Obama’s proposal to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Another comparison that might be useful is the loss of potential GDP due to the austerity measures demanded by the Republican Congress and supported by many Democrats. In 2008, before the financial crisis, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that potential GDP in 2016 would 22.5 percent higher than in 2008. It now projects that potential GDP in 2016 is just 12.0 percent higher in 2016 than it was in 2008.

This decline in potential GDP is roughly ten times as large as the projected costs from meeting President Obama’s targets for greenhouse gas emissions. Even if just half of this cost was due to austerity (as opposed to a mistaken projection by CBO in 2008 or unavoidable costs of the crisis) then the cost of austerity would still be more than five times as large as the costs of meeting President Obama’s targets for greenhouse gas emissions.

And, as the piece notes, the estimates do not take account of any benefits from reduced damage to the environment. For example, we might have fewer destructive storms, flooding of coastal regions, and forest fires in drought afflicted regions.

It is also worth noting that the WSJ piece entirely focuses on the high-end estimate in the study, the low-end estimate is just over one quarter as large.

These are all reasons why readers might not take the conclusion of the piece very seriously:

“‘It’s a sad comment on the political debate. This will affect people’s children and grandchildren,’ Mr. Heal [the author of the study] said.”

That is what they warned, but they didn’t quite put it to readers that way. Instead the subhead warned that meeting President Obama’s goal of reducing emissions by 80 percent by 2050 would cost $5.28 trillion.

Yes folks, that sounds pretty scary. After all, $5.28 trillion over the next 34 years is bigger than a bread box, possibly much bigger.

Of course, it is unlikely that many of the WSJ’s readers have a clear idea of how big the economy will be over this 34-year period, so they are not likely to be in a good position to assess how much of a burden this would be. Since annual output will average more than $20 trillion a year (in 2016 dollars), this sum comes to about 0.9 percent of projected GDP. (This context is included near the bottom of the piece.) By comparison, the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars at their peak was roughly 2.0 percent of GDP, implying that they imposed more than twice the burden on the economy as President Obama’s proposal to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Another comparison that might be useful is the loss of potential GDP due to the austerity measures demanded by the Republican Congress and supported by many Democrats. In 2008, before the financial crisis, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that potential GDP in 2016 would 22.5 percent higher than in 2008. It now projects that potential GDP in 2016 is just 12.0 percent higher in 2016 than it was in 2008.

This decline in potential GDP is roughly ten times as large as the projected costs from meeting President Obama’s targets for greenhouse gas emissions. Even if just half of this cost was due to austerity (as opposed to a mistaken projection by CBO in 2008 or unavoidable costs of the crisis) then the cost of austerity would still be more than five times as large as the costs of meeting President Obama’s targets for greenhouse gas emissions.

And, as the piece notes, the estimates do not take account of any benefits from reduced damage to the environment. For example, we might have fewer destructive storms, flooding of coastal regions, and forest fires in drought afflicted regions.

It is also worth noting that the WSJ piece entirely focuses on the high-end estimate in the study, the low-end estimate is just over one quarter as large.

These are all reasons why readers might not take the conclusion of the piece very seriously:

“‘It’s a sad comment on the political debate. This will affect people’s children and grandchildren,’ Mr. Heal [the author of the study] said.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT has a major piece on the skepticism towards Hillary Clinton’s job creation proposals in the coal mining regions of Virginia. While there undoubtedly is much ground for skepticism about the prospects for such proposals, it is worth noting that most of the coal mining jobs in this region were lost long ago.

Employment in coal mining in Virginia peaked at just under 25,000 in 1982. By 1992 it was under 14,000 and it was below 10,000 by the end of the decade.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Since 2000, the number of mining jobs has generally stayed close to 10,000, but it has fallen off to 8,300 over the last three years according the Bureau of Labor Statistics new series on mining jobs. While any job loss is a horrible story for the people directly affected, especially when it occurs in an already depressed region, the bulk of the mining jobs had been lost more than two decades ago.

In other words, the loss of mining jobs is not something new due to efforts to slow global warming. It is due to increased productivity in the coal industry, and more recently, competition from low cost natural gas from fracking.

The NYT has a major piece on the skepticism towards Hillary Clinton’s job creation proposals in the coal mining regions of Virginia. While there undoubtedly is much ground for skepticism about the prospects for such proposals, it is worth noting that most of the coal mining jobs in this region were lost long ago.

Employment in coal mining in Virginia peaked at just under 25,000 in 1982. By 1992 it was under 14,000 and it was below 10,000 by the end of the decade.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Since 2000, the number of mining jobs has generally stayed close to 10,000, but it has fallen off to 8,300 over the last three years according the Bureau of Labor Statistics new series on mining jobs. While any job loss is a horrible story for the people directly affected, especially when it occurs in an already depressed region, the bulk of the mining jobs had been lost more than two decades ago.

In other words, the loss of mining jobs is not something new due to efforts to slow global warming. It is due to increased productivity in the coal industry, and more recently, competition from low cost natural gas from fracking.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

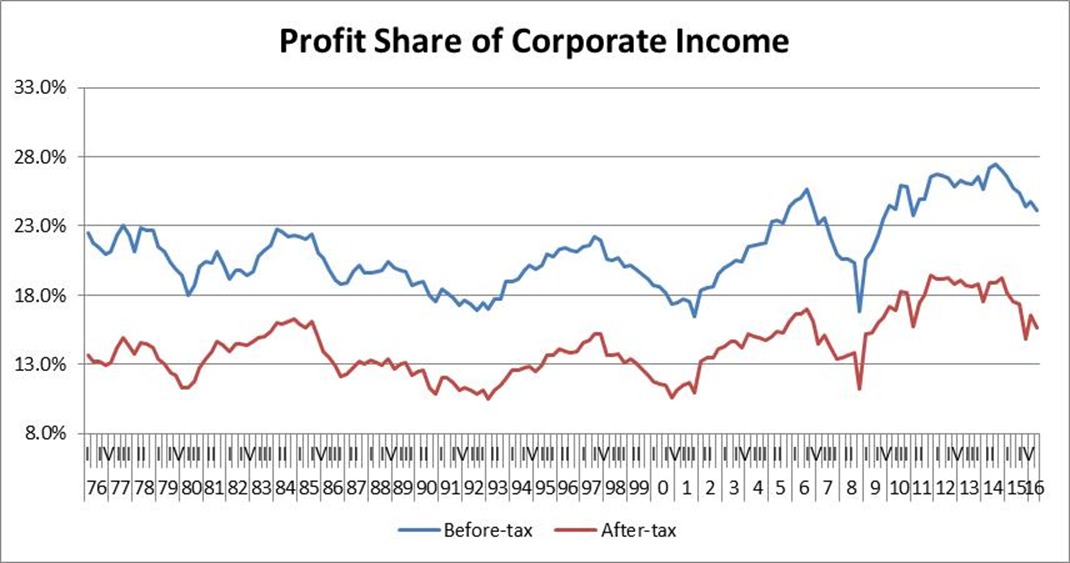

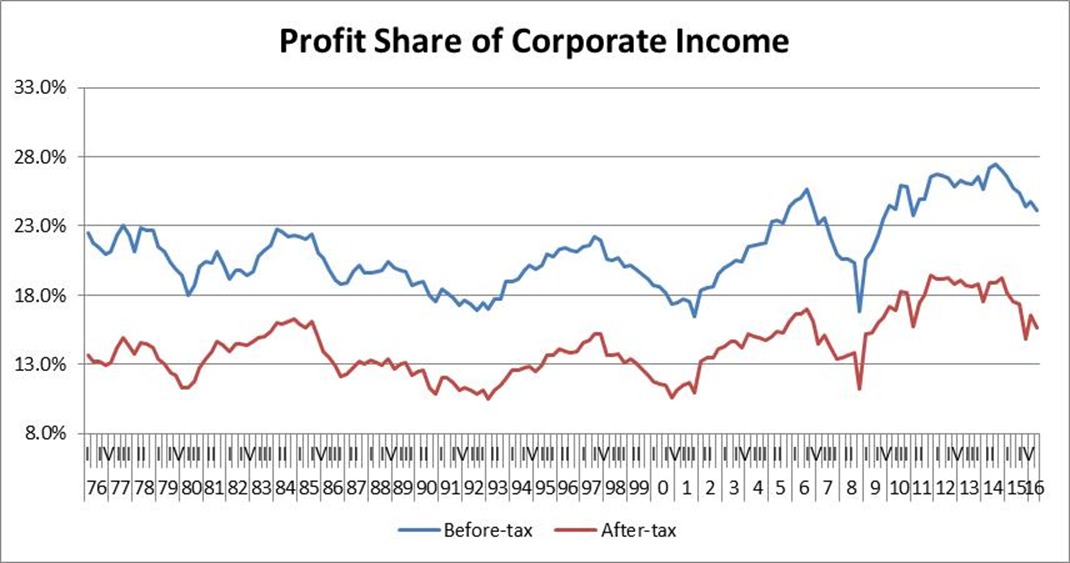

The Commerce Department released data on corporate profits along with its preliminary GDP report for the second quarter of 2016. It showed that the profit share of corporate income is continuing to edge downward. The before tax share of corporate profits (net operating surplus) was 24.2 percent in the second quarter of 2016. This is down from a peak of 27.4 percent in the third quarter of 2014, but still well above 20.4 percent average for the four decades prior to the collapse of the housing bubble. With profit data it is always important to include the caution that the numbers are erratic and subject to large revisions.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The Commerce Department released data on corporate profits along with its preliminary GDP report for the second quarter of 2016. It showed that the profit share of corporate income is continuing to edge downward. The before tax share of corporate profits (net operating surplus) was 24.2 percent in the second quarter of 2016. This is down from a peak of 27.4 percent in the third quarter of 2014, but still well above 20.4 percent average for the four decades prior to the collapse of the housing bubble. With profit data it is always important to include the caution that the numbers are erratic and subject to large revisions.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a good piece about how the Federal Reserve Board is responding to protests of Fed policy and insufficient concern about unemployment by the group Fed Up. (CEPR is affiliated with the Fed Up campaign.) At one point the piece quotes Esther George, the president of the Kansas City Fed, as saying that she is sympathetic to concerns about unemployment, but that if the Fed is too slow in raising interest rates it can lead to inflation and asset bubbles.

It is worth noting that Ms. George has been expressing this concern about inflation for the last three and a half years, a period in which there has been no noticeable increase in the inflation rate. While there are real reasons to be concerned about asset bubbles (like the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade), higher interest rates are a very poor tool for combating bubbles.

The New York Times had a good piece about how the Federal Reserve Board is responding to protests of Fed policy and insufficient concern about unemployment by the group Fed Up. (CEPR is affiliated with the Fed Up campaign.) At one point the piece quotes Esther George, the president of the Kansas City Fed, as saying that she is sympathetic to concerns about unemployment, but that if the Fed is too slow in raising interest rates it can lead to inflation and asset bubbles.

It is worth noting that Ms. George has been expressing this concern about inflation for the last three and a half years, a period in which there has been no noticeable increase in the inflation rate. While there are real reasons to be concerned about asset bubbles (like the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade), higher interest rates are a very poor tool for combating bubbles.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post reported that Uber is deliberately trying to drive Lyft, its major competitor out of the market, by having temporarily low rates and subsidies to drivers. If the Post’s reporting is accurate, and barriers to entry prevent new companies from effectively competing with Uber, then the company is engaging in classic anti-competitive tactics. This is the sort of activity that is supposed bring intervention from the Justice Department, since Uber will be charging higher prices if it succeeds in eliminating Lyft.

The management of Uber is either not aware of the law or counting on its political power to ensure that the law is not enforced. Uber hired David Plouffe, President Obama’s top political strategist, to a top position in 2008.

The Washington Post reported that Uber is deliberately trying to drive Lyft, its major competitor out of the market, by having temporarily low rates and subsidies to drivers. If the Post’s reporting is accurate, and barriers to entry prevent new companies from effectively competing with Uber, then the company is engaging in classic anti-competitive tactics. This is the sort of activity that is supposed bring intervention from the Justice Department, since Uber will be charging higher prices if it succeeds in eliminating Lyft.

The management of Uber is either not aware of the law or counting on its political power to ensure that the law is not enforced. Uber hired David Plouffe, President Obama’s top political strategist, to a top position in 2008.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión