President Obama is working hard to push the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), going around the country promoting the pact. He must want Congress to approve it before he leaves office.

That much would be obvious to anyone. But Politico uses its incredible mind reading ability to go a step further. It tells us:

“Obama has been unwilling to abandon a deal that he regards as central to his legacy.”

The rest of us might be able to know that Obama says that he regards the TPP central to his legacy, but lacking Politico’s mind reading skills we wouldn’t know that he actually does regard the TPP as central to his legacy. Since President Obama is a politician, we know that he doesn’t always say exactly what he thinks, so we may not know whether or not he regards the TPP as central to his legacy.

We could believe that the is pushing the deal as a favor to the powerful business interests that helped to negotiate the deal, like the pharmaceutical industry, the entertainment industry, and the financial industry. These industries are expected to be major donors to Democratic campaigns this fall.

Of course, it would be difficult to get approval for the TPP based on the argument that it would benefit contributors to the Democratic Party. Since President Obama is popular with the country as a whole, and enormously popular among Democrats, it is a much stronger argument to make voting against the deal a personal affront to the president. So it is entirely understandable that President Obama would want the public to have him believe that he sees the TPP as central to his legacy.

Thankfully, we have Politico and the mind readers on its staff who can tell us that President Obama is not acting as a politician but rather he actually believes this claim.

President Obama is working hard to push the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), going around the country promoting the pact. He must want Congress to approve it before he leaves office.

That much would be obvious to anyone. But Politico uses its incredible mind reading ability to go a step further. It tells us:

“Obama has been unwilling to abandon a deal that he regards as central to his legacy.”

The rest of us might be able to know that Obama says that he regards the TPP central to his legacy, but lacking Politico’s mind reading skills we wouldn’t know that he actually does regard the TPP as central to his legacy. Since President Obama is a politician, we know that he doesn’t always say exactly what he thinks, so we may not know whether or not he regards the TPP as central to his legacy.

We could believe that the is pushing the deal as a favor to the powerful business interests that helped to negotiate the deal, like the pharmaceutical industry, the entertainment industry, and the financial industry. These industries are expected to be major donors to Democratic campaigns this fall.

Of course, it would be difficult to get approval for the TPP based on the argument that it would benefit contributors to the Democratic Party. Since President Obama is popular with the country as a whole, and enormously popular among Democrats, it is a much stronger argument to make voting against the deal a personal affront to the president. So it is entirely understandable that President Obama would want the public to have him believe that he sees the TPP as central to his legacy.

Thankfully, we have Politico and the mind readers on its staff who can tell us that President Obama is not acting as a politician but rather he actually believes this claim.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steve Pearlstein used a Washington Post column to correct an earlier scare story about robots taking all the jobs by fellow columnist David Ignatius. Pearlstein gets the story mostly right. If robots reduce the need for labor then someone will have additional money to spend. Either workers will get higher wages or prices of the goods produced by robots will fall, allowing people to buy more stuff. Most likely it will be some combination, but there is no basis for assuming that there will be no demand for workers. (This is true even if it goes to profits, since rich people will hire more help.)

There are two important qualifications to this argument. First, there is no evidence of massive displacement of workers by robots. This is exactly what productivity is about. Productivity is how much the economy produces for each hour of human (non-robot) labor. If robots were taking jobs in large numbers then productivity growth would be very rapid. In fact, productivity growth has been very slow. It actually has been negative in the last three quarters.

Of course this could change, maybe the robots are lurking just around the corner. But for now, just about all the economists I know are worried about the slow pace of productivity growth, not a huge surge in productivity displacing tens of millions of workers.

The other point that needs to be plastered across the top of Trump tower, is that when people benefit from “owning” technology it is because the government has chosen to subsidize their innovations. The issue here is patent protection, which is a main reason why the benefits of technology often are not widely shared. Patents give their owners monopolies over technology which allows them to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price.

There is an obvious rationale for patents — they give individuals and corporations an incentive to innovate. But in the last four decades we have implemented a variety of policies designed to make patent protection stronger and longer. As a result, more money is going to people who own patents. This money comes out of the pockets of the rest of us.

It is possible to argue that the strengthening of patents has been justified by its effect in promoting innovation (weak productivity growth suggests otherwise), but the fact this was a policy choice is not arguable. So when someone says that “technology” has caused inequality they are displaying their ignorance. Insofar as new technologies have been responsible for an upward redistribution of income, it has been the result of the political decision to provide these technologies with patent monopolies.

In other words, it is the folks in Congress and the White House who are responsible, not the robots.

Steve Pearlstein used a Washington Post column to correct an earlier scare story about robots taking all the jobs by fellow columnist David Ignatius. Pearlstein gets the story mostly right. If robots reduce the need for labor then someone will have additional money to spend. Either workers will get higher wages or prices of the goods produced by robots will fall, allowing people to buy more stuff. Most likely it will be some combination, but there is no basis for assuming that there will be no demand for workers. (This is true even if it goes to profits, since rich people will hire more help.)

There are two important qualifications to this argument. First, there is no evidence of massive displacement of workers by robots. This is exactly what productivity is about. Productivity is how much the economy produces for each hour of human (non-robot) labor. If robots were taking jobs in large numbers then productivity growth would be very rapid. In fact, productivity growth has been very slow. It actually has been negative in the last three quarters.

Of course this could change, maybe the robots are lurking just around the corner. But for now, just about all the economists I know are worried about the slow pace of productivity growth, not a huge surge in productivity displacing tens of millions of workers.

The other point that needs to be plastered across the top of Trump tower, is that when people benefit from “owning” technology it is because the government has chosen to subsidize their innovations. The issue here is patent protection, which is a main reason why the benefits of technology often are not widely shared. Patents give their owners monopolies over technology which allows them to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price.

There is an obvious rationale for patents — they give individuals and corporations an incentive to innovate. But in the last four decades we have implemented a variety of policies designed to make patent protection stronger and longer. As a result, more money is going to people who own patents. This money comes out of the pockets of the rest of us.

It is possible to argue that the strengthening of patents has been justified by its effect in promoting innovation (weak productivity growth suggests otherwise), but the fact this was a policy choice is not arguable. So when someone says that “technology” has caused inequality they are displaying their ignorance. Insofar as new technologies have been responsible for an upward redistribution of income, it has been the result of the political decision to provide these technologies with patent monopolies.

In other words, it is the folks in Congress and the White House who are responsible, not the robots.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT’s Dealbook section ran an interesting column on the “risks of unfettered capitalism” by St. John University Law Professor Jeff Sovern. The piece lists a number of abuses by corporations, including Volkswagen’s diesel scandal, Vioxx, and predatory lending. While Sovern is right in arguing for the need to rein in these abuses, it’s questionable whether this is an issue of “unfettered” capitalism.

In the case of Volkswagen, they deliberately lied to their customers about the product they were buying. Many of the people buying Volkswagen’s diesel cars were buying them explicitly because they wanted an environmentally friendly cars. It is not clear that it is accurate to call a system of capitalism “unfettered” if companies are allowed to lie to make money from their customers. Would this mean that in “unfettered” capitalism, airlines could charge people in advance for a plane ticket and then not actually give them a seat on the plane? That would be equating unfettered capitalism with legalized fraud.

In the case of Vioxx, Merck was alleged to have deliberately withheld evidence that the arthritis drug posed risks to patients with heart conditions. Its motivation was to increase sales. The reason that Merck had such a large incentive to increase sales was that the government gave them a patent monopoly that allowed it to sell Vioxx at a price that was several thousand percent above its free market price.

Without this patent monopoly, Merck’s profit margin on Vioxx would have been comparable to the margins that companies make selling paper cups and pencils. These sorts of profit margins would not likely have provided the sort of incentive to conceal evidence at the risk of patients’ health and life. It is hard to see how a government-granted patent monopoly can be seen as unfettered capitalism.

In the case of predatory lending, the question is whether companies can use deceptive practices to get people to take out loans if they do not fully understand the terms. The logic here is that smart people trained in law can write complicated contracts that a typical customer is not likely to be able to understand without spending a great deal of time and effort reviewing it.

If we allow for complex contracts with consumers to be enforceable, then we are providing an incentive for highly trained lawyers to spend a great deal of time figuring out how to design complex, deceptive contracts. We also then will effectively force consumers to spend far more time reviewing contracts to ensure that they are not being ripped off. This is an enormous waste of resources which is also likely to result in an upward redistribution of income.

As is the case here, in many instances where people claim they are talking about unfettered capitalism, they are actually talking about one person’s “right” to dump their sewage on their neighbor’s lawn. The dumper is invariably more powerful than the dumpee. It gives the issue way more respect than it deserves to ascribe to it a principle like “unfettered capitalism.” It’s really just a question of whether we want a system where the rich are allowed to rip off everyone else.

The NYT’s Dealbook section ran an interesting column on the “risks of unfettered capitalism” by St. John University Law Professor Jeff Sovern. The piece lists a number of abuses by corporations, including Volkswagen’s diesel scandal, Vioxx, and predatory lending. While Sovern is right in arguing for the need to rein in these abuses, it’s questionable whether this is an issue of “unfettered” capitalism.

In the case of Volkswagen, they deliberately lied to their customers about the product they were buying. Many of the people buying Volkswagen’s diesel cars were buying them explicitly because they wanted an environmentally friendly cars. It is not clear that it is accurate to call a system of capitalism “unfettered” if companies are allowed to lie to make money from their customers. Would this mean that in “unfettered” capitalism, airlines could charge people in advance for a plane ticket and then not actually give them a seat on the plane? That would be equating unfettered capitalism with legalized fraud.

In the case of Vioxx, Merck was alleged to have deliberately withheld evidence that the arthritis drug posed risks to patients with heart conditions. Its motivation was to increase sales. The reason that Merck had such a large incentive to increase sales was that the government gave them a patent monopoly that allowed it to sell Vioxx at a price that was several thousand percent above its free market price.

Without this patent monopoly, Merck’s profit margin on Vioxx would have been comparable to the margins that companies make selling paper cups and pencils. These sorts of profit margins would not likely have provided the sort of incentive to conceal evidence at the risk of patients’ health and life. It is hard to see how a government-granted patent monopoly can be seen as unfettered capitalism.

In the case of predatory lending, the question is whether companies can use deceptive practices to get people to take out loans if they do not fully understand the terms. The logic here is that smart people trained in law can write complicated contracts that a typical customer is not likely to be able to understand without spending a great deal of time and effort reviewing it.

If we allow for complex contracts with consumers to be enforceable, then we are providing an incentive for highly trained lawyers to spend a great deal of time figuring out how to design complex, deceptive contracts. We also then will effectively force consumers to spend far more time reviewing contracts to ensure that they are not being ripped off. This is an enormous waste of resources which is also likely to result in an upward redistribution of income.

As is the case here, in many instances where people claim they are talking about unfettered capitalism, they are actually talking about one person’s “right” to dump their sewage on their neighbor’s lawn. The dumper is invariably more powerful than the dumpee. It gives the issue way more respect than it deserves to ascribe to it a principle like “unfettered capitalism.” It’s really just a question of whether we want a system where the rich are allowed to rip off everyone else.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

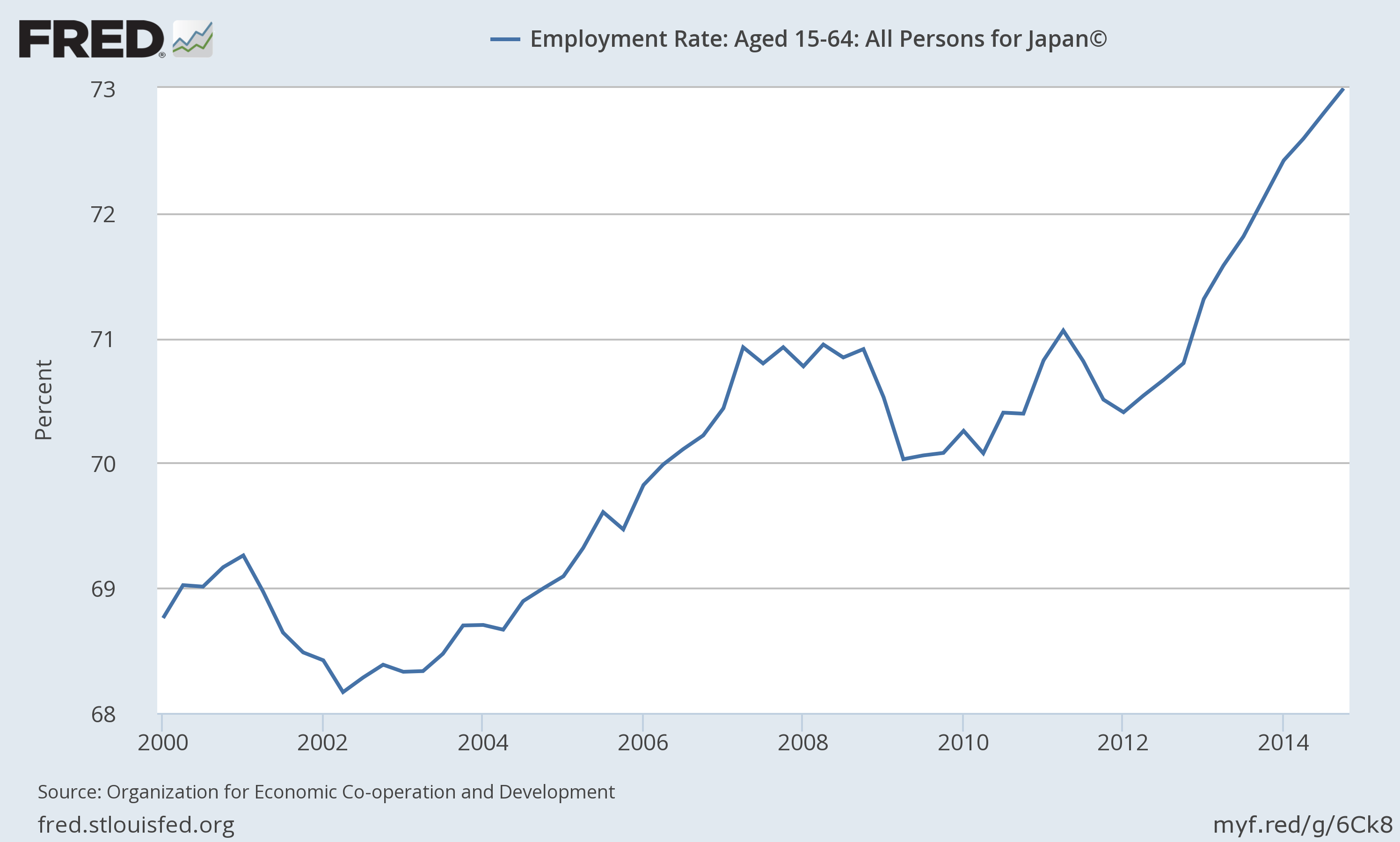

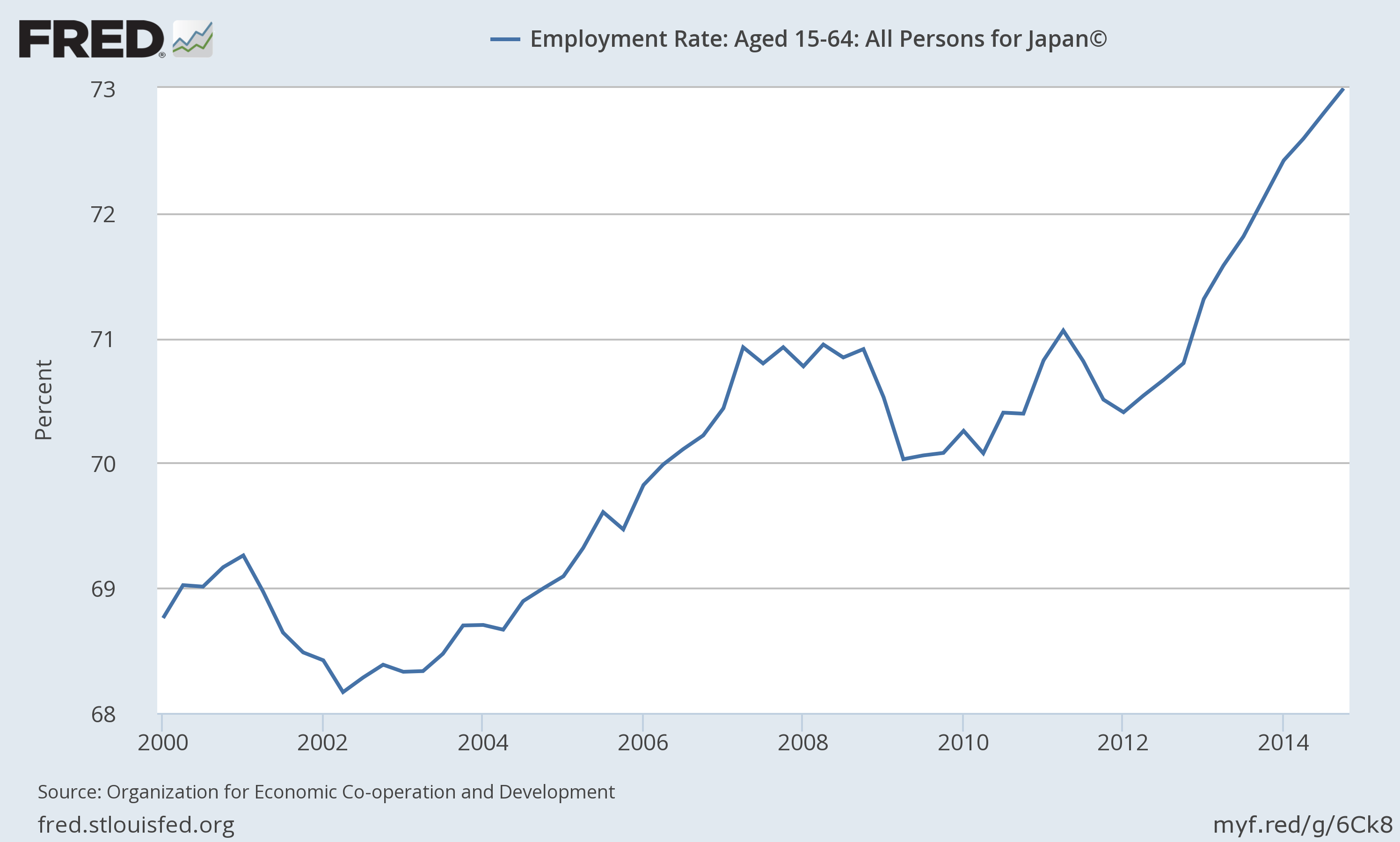

This short piece on Japan’s GDP growth reminded me that I wanted to post a graph showing the rise in Japan’s employment rate under Abe. Here’s the basic picture showing the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) for people between the ages of 16 and 64 since 2000.

As can seen, Japan’s EPOP fell following the 2001 recession. It had made up lost ground by 2005 and continued to rise until 2007. It stagnated for roughly two years and then rose somewhat before starting to drop again in 2011. It was falling when Abe took over in December of 2012.

Since then the EPOP has risen by 2.5 percentage points. This is a huge gain that would be equivalent to another 6.2 million jobs in the United States. Japan’s growth has certainly not be inspiring under Abe, but this increase in employment is quite impressive. By this measure, Abenomics has been very successful.

This short piece on Japan’s GDP growth reminded me that I wanted to post a graph showing the rise in Japan’s employment rate under Abe. Here’s the basic picture showing the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) for people between the ages of 16 and 64 since 2000.

As can seen, Japan’s EPOP fell following the 2001 recession. It had made up lost ground by 2005 and continued to rise until 2007. It stagnated for roughly two years and then rose somewhat before starting to drop again in 2011. It was falling when Abe took over in December of 2012.

Since then the EPOP has risen by 2.5 percentage points. This is a huge gain that would be equivalent to another 6.2 million jobs in the United States. Japan’s growth has certainly not be inspiring under Abe, but this increase in employment is quite impressive. By this measure, Abenomics has been very successful.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting piece charting the career paths of Bill and Hillary Clinton, and the extent to which they may have had financial concerns earlier in their lives. Unfortunately, the piece does not adjust for inflation, so it may have misled readers about how well off the Clinton’s actually were.

For example, the piece tells readers that after Bill Clinton lost his re-election bid in 1980:

“The Clintons had stretched their finances to afford the $112,000 home, which was down the hill from the city’s old-money mansions.”

That home would cost a bit more than $280,000 in today’s dollars.

A bit further down the piece tells readers that Hillary took a job at a law firm for $55,000 a year. That would be roughly $158,000 a year in today’s dollars. It also refers to them earning $18,000 a year each as law professors in Fayetteville in 1975. That would be a bit more than $135,000 in today’s dollars for their combined income.

The $100,000 that Hillary Clinton reportedly made speculating in cattle futures in 1978 would be more than $330,000 in today’s dollars.

The $33,500 that Bill Clinton earned Arkansas’s governor in 1978 would be just under $112,000 in today’s dollars and their combined income of $51,200 for that year would be just over $170,000. The $297,000 they reported as combined income 1992 would be equal to more than $490,000 in today’s dollars.

It is also worth noting that Arkansas is one of the poorest states in the country and has a much lower cost of living than wealthier areas like the Northeast or California.

Thanks to Keane Bhatt for calling this to my attention.

Note: The professor salary adjustment was corrected to clearly indicate it refers to their combined income.

The NYT had an interesting piece charting the career paths of Bill and Hillary Clinton, and the extent to which they may have had financial concerns earlier in their lives. Unfortunately, the piece does not adjust for inflation, so it may have misled readers about how well off the Clinton’s actually were.

For example, the piece tells readers that after Bill Clinton lost his re-election bid in 1980:

“The Clintons had stretched their finances to afford the $112,000 home, which was down the hill from the city’s old-money mansions.”

That home would cost a bit more than $280,000 in today’s dollars.

A bit further down the piece tells readers that Hillary took a job at a law firm for $55,000 a year. That would be roughly $158,000 a year in today’s dollars. It also refers to them earning $18,000 a year each as law professors in Fayetteville in 1975. That would be a bit more than $135,000 in today’s dollars for their combined income.

The $100,000 that Hillary Clinton reportedly made speculating in cattle futures in 1978 would be more than $330,000 in today’s dollars.

The $33,500 that Bill Clinton earned Arkansas’s governor in 1978 would be just under $112,000 in today’s dollars and their combined income of $51,200 for that year would be just over $170,000. The $297,000 they reported as combined income 1992 would be equal to more than $490,000 in today’s dollars.

It is also worth noting that Arkansas is one of the poorest states in the country and has a much lower cost of living than wealthier areas like the Northeast or California.

Thanks to Keane Bhatt for calling this to my attention.

Note: The professor salary adjustment was corrected to clearly indicate it refers to their combined income.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting piece on the pharmaceutical market in India, which just began recognizing patent monopolies on drugs a decade ago. Corruption and abusive sales practices of the sort described in the piece are exactly what economic theory predicts when tariffs of several hundred or several thousand percent are imposed in a market. While “free traders” like to ignore the harm from patent monopolies that raise the price of the protected items by these amounts, the market does not care whether the cause of an artifically high price is called a “patent” or a “tariff,” it has the same effect.

The NYT had an interesting piece on the pharmaceutical market in India, which just began recognizing patent monopolies on drugs a decade ago. Corruption and abusive sales practices of the sort described in the piece are exactly what economic theory predicts when tariffs of several hundred or several thousand percent are imposed in a market. While “free traders” like to ignore the harm from patent monopolies that raise the price of the protected items by these amounts, the market does not care whether the cause of an artifically high price is called a “patent” or a “tariff,” it has the same effect.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT weakly posed this question in an article reporting on the proliferation of scripted TV shows coming largely from newcomers like Netflix. The concerns expressed about too much TV were more than a bit bizarre. For example, it told readers:

“sharing Mr. Landgraf’s [CEO at FX Networks] concern, some TV executives have said that they also felt audiences were becoming fatigued and having a difficult time finding the best shows out of the glut.”

Really? People are getting tired from going through the listings of all the shows? Do they get tired from going through listings of books? I suppose it’s possible, but it seems more likely that people would watch shows that they happen to hear good things about and ignore the rest.

There is a plausible story to tell about the proliferation of shows. With many more shows commanding an audience, there will be fewer shows that will command the sort of audience that would justify big budget productions. That means fewer writers, actors, directors will be able to command big paychecks.

This is certainly bad news for the tiny group in the big paycheck crowd, but it is great news for all writers, actors, directors that will be able to make a decent living in the smaller audience productions. And, since this will have been the result of people opting to watch the smaller audience productions, it’s hard to see why we should be troubled by the situation (unless we work for the big paycheck crowd).

The NYT weakly posed this question in an article reporting on the proliferation of scripted TV shows coming largely from newcomers like Netflix. The concerns expressed about too much TV were more than a bit bizarre. For example, it told readers:

“sharing Mr. Landgraf’s [CEO at FX Networks] concern, some TV executives have said that they also felt audiences were becoming fatigued and having a difficult time finding the best shows out of the glut.”

Really? People are getting tired from going through the listings of all the shows? Do they get tired from going through listings of books? I suppose it’s possible, but it seems more likely that people would watch shows that they happen to hear good things about and ignore the rest.

There is a plausible story to tell about the proliferation of shows. With many more shows commanding an audience, there will be fewer shows that will command the sort of audience that would justify big budget productions. That means fewer writers, actors, directors will be able to command big paychecks.

This is certainly bad news for the tiny group in the big paycheck crowd, but it is great news for all writers, actors, directors that will be able to make a decent living in the smaller audience productions. And, since this will have been the result of people opting to watch the smaller audience productions, it’s hard to see why we should be troubled by the situation (unless we work for the big paycheck crowd).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a Reuters piece on the future of drug pricing. Guess what? No one is talking about good old-fashioned free market prices. The word from Reuters is that in the future drug companies will be paid based on the benefits provided by their drugs, not a per pill charge. As described in the piece, drug companies would be compensated by insurers for the use of their drugs based on the average improvement in health per patient treated.

As the piece hints, this will be an incredible burden to calculate, especially for drugs that are used on limited numbers of patients who may also suffer from multiple conditions. The situation gets even more complicated when we take into account the possibility that a drug could have serious side-effects that won’t be discovered until many years after it is in use. I suppose in that situation we go back and collect the payments that were made to the company earlier from the shareholders and their children.

For some reason, the idea of just funding the research upfront and putting in the public domain seems to be out of bounds. Reuters, and implicitly the NYT, would apparently prefer all sorts of bizarre bureaucratic fixes rather than something that would almost certainly be far simpler and cheaper and not leave sick people struggling to find ways to pay for drugs that are necessary for their life or health.

The NYT ran a Reuters piece on the future of drug pricing. Guess what? No one is talking about good old-fashioned free market prices. The word from Reuters is that in the future drug companies will be paid based on the benefits provided by their drugs, not a per pill charge. As described in the piece, drug companies would be compensated by insurers for the use of their drugs based on the average improvement in health per patient treated.

As the piece hints, this will be an incredible burden to calculate, especially for drugs that are used on limited numbers of patients who may also suffer from multiple conditions. The situation gets even more complicated when we take into account the possibility that a drug could have serious side-effects that won’t be discovered until many years after it is in use. I suppose in that situation we go back and collect the payments that were made to the company earlier from the shareholders and their children.

For some reason, the idea of just funding the research upfront and putting in the public domain seems to be out of bounds. Reuters, and implicitly the NYT, would apparently prefer all sorts of bizarre bureaucratic fixes rather than something that would almost certainly be far simpler and cheaper and not leave sick people struggling to find ways to pay for drugs that are necessary for their life or health.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión