Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

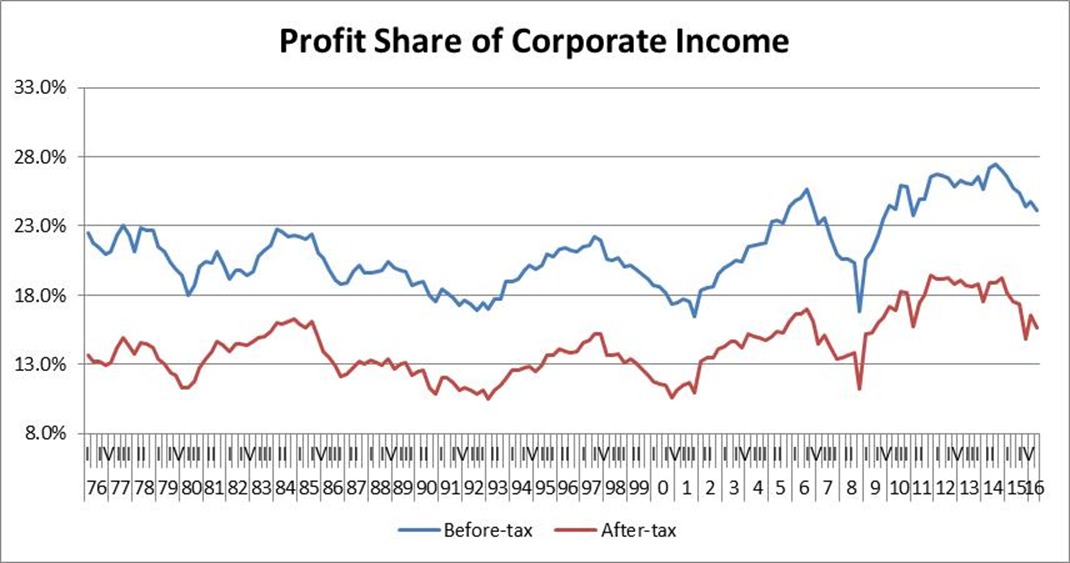

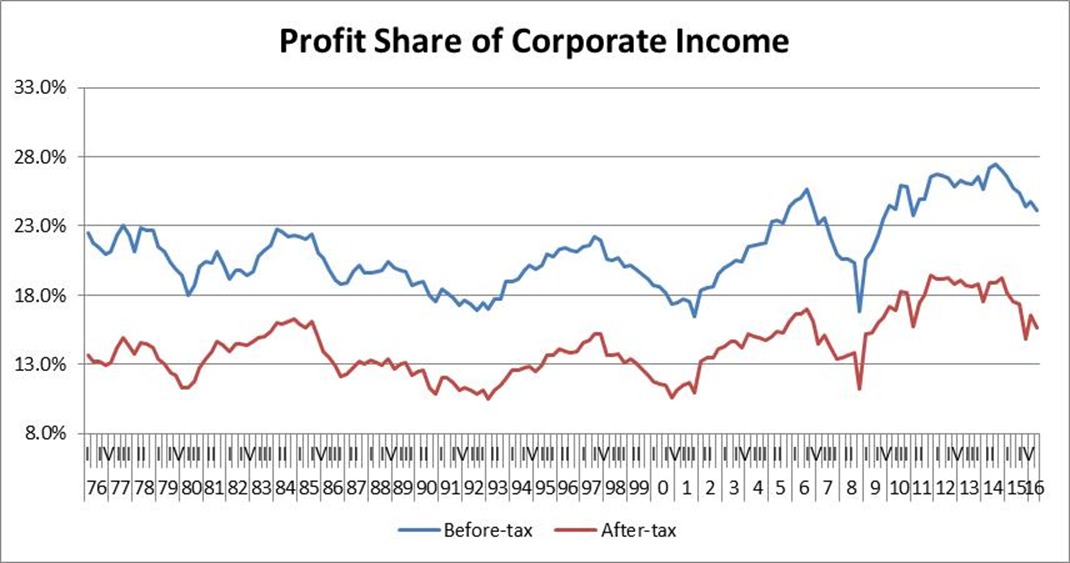

The Commerce Department released data on corporate profits along with its preliminary GDP report for the second quarter of 2016. It showed that the profit share of corporate income is continuing to edge downward. The before tax share of corporate profits (net operating surplus) was 24.2 percent in the second quarter of 2016. This is down from a peak of 27.4 percent in the third quarter of 2014, but still well above 20.4 percent average for the four decades prior to the collapse of the housing bubble. With profit data it is always important to include the caution that the numbers are erratic and subject to large revisions.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The Commerce Department released data on corporate profits along with its preliminary GDP report for the second quarter of 2016. It showed that the profit share of corporate income is continuing to edge downward. The before tax share of corporate profits (net operating surplus) was 24.2 percent in the second quarter of 2016. This is down from a peak of 27.4 percent in the third quarter of 2014, but still well above 20.4 percent average for the four decades prior to the collapse of the housing bubble. With profit data it is always important to include the caution that the numbers are erratic and subject to large revisions.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a good piece about how the Federal Reserve Board is responding to protests of Fed policy and insufficient concern about unemployment by the group Fed Up. (CEPR is affiliated with the Fed Up campaign.) At one point the piece quotes Esther George, the president of the Kansas City Fed, as saying that she is sympathetic to concerns about unemployment, but that if the Fed is too slow in raising interest rates it can lead to inflation and asset bubbles.

It is worth noting that Ms. George has been expressing this concern about inflation for the last three and a half years, a period in which there has been no noticeable increase in the inflation rate. While there are real reasons to be concerned about asset bubbles (like the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade), higher interest rates are a very poor tool for combating bubbles.

The New York Times had a good piece about how the Federal Reserve Board is responding to protests of Fed policy and insufficient concern about unemployment by the group Fed Up. (CEPR is affiliated with the Fed Up campaign.) At one point the piece quotes Esther George, the president of the Kansas City Fed, as saying that she is sympathetic to concerns about unemployment, but that if the Fed is too slow in raising interest rates it can lead to inflation and asset bubbles.

It is worth noting that Ms. George has been expressing this concern about inflation for the last three and a half years, a period in which there has been no noticeable increase in the inflation rate. While there are real reasons to be concerned about asset bubbles (like the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade), higher interest rates are a very poor tool for combating bubbles.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post reported that Uber is deliberately trying to drive Lyft, its major competitor out of the market, by having temporarily low rates and subsidies to drivers. If the Post’s reporting is accurate, and barriers to entry prevent new companies from effectively competing with Uber, then the company is engaging in classic anti-competitive tactics. This is the sort of activity that is supposed bring intervention from the Justice Department, since Uber will be charging higher prices if it succeeds in eliminating Lyft.

The management of Uber is either not aware of the law or counting on its political power to ensure that the law is not enforced. Uber hired David Plouffe, President Obama’s top political strategist, to a top position in 2008.

The Washington Post reported that Uber is deliberately trying to drive Lyft, its major competitor out of the market, by having temporarily low rates and subsidies to drivers. If the Post’s reporting is accurate, and barriers to entry prevent new companies from effectively competing with Uber, then the company is engaging in classic anti-competitive tactics. This is the sort of activity that is supposed bring intervention from the Justice Department, since Uber will be charging higher prices if it succeeds in eliminating Lyft.

The management of Uber is either not aware of the law or counting on its political power to ensure that the law is not enforced. Uber hired David Plouffe, President Obama’s top political strategist, to a top position in 2008.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Ignatius used his WaPo column to express his concern that Australia will opt to align itself more closely with China at the expense of its ties with the United States. In making the argument that other regional powers may provide an offset to China, Ignatius cites Indonesia, which he notes has seen its per capita income increase by 50 percent while China’s economy is slowing.

While Indonesia’s growth has been pretty good over this period, China’s per capita GDP increased by 136 percent over the same period. Even with its slowdown its economy is still growing more rapidly than Indonesia’s. It does not seem likely that Indonesia will gain economic strength relative to China any time soon.

David Ignatius used his WaPo column to express his concern that Australia will opt to align itself more closely with China at the expense of its ties with the United States. In making the argument that other regional powers may provide an offset to China, Ignatius cites Indonesia, which he notes has seen its per capita income increase by 50 percent while China’s economy is slowing.

While Indonesia’s growth has been pretty good over this period, China’s per capita GDP increased by 136 percent over the same period. Even with its slowdown its economy is still growing more rapidly than Indonesia’s. It does not seem likely that Indonesia will gain economic strength relative to China any time soon.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Sebastian Mallaby had a column in the WaPo on the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target. Mallaby argues that the 2.0 percent target is arbitrary and makes the case that moving to a higher inflation target, as recently suggested by San Francisco bank president John Williams, would be desirable.

While Mallaby makes some good points, he also gets some items wrong. First, he notes the Fed’s decision to ignore the growth of the housing bubble in the last decade. He said that they viewed the issue of financial stability as one appropriately left to regulators, not a concern for monetary policy. This is largely right, but it ignores the point that the Fed also has enormous regulatory power, including the responsibility for oversight on the issuance of mortgages.

Alan Greenspan essentially ignored these responsibilities, seeing them as inconsequential.This is largely because he didn’t see bubbles as any big deal, or at least this is what he publicly said in a speech he gave at the American Economics Association convention in January of 2004. In this speech he patted himself on the back for having the good sense to let the stock bubble run its course and then pick up the pieces after it burst. (The next day, Ben Bernanke, who was then a Fed governor, explained why it was necessary to still have a 1.0 percent federal funds rate, more than two years after the recession had officially ended. This suggested it was not easy to pick up the pieces.)

The other area where Mallaby is not exactly on target is in discussing the Fed’s tools. While he is correct in arguing that the Fed has more room to lower the federal funds rate in the context of a higher inflation rate, it is not right that this is its only tool. The Fed could target a long-term interest rate. For example, it could set a target of 1.0 percent for the 10-year Treasury rate for the next year.

This sort of targeting of a longer term rate would provide a more direct boost to growth than lowering the federal funds rate. While it might be desirable to rely on a more known tool for monetary policy, it is wrong to imply that there is nothing more the Fed can do to boost growth.

Sebastian Mallaby had a column in the WaPo on the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target. Mallaby argues that the 2.0 percent target is arbitrary and makes the case that moving to a higher inflation target, as recently suggested by San Francisco bank president John Williams, would be desirable.

While Mallaby makes some good points, he also gets some items wrong. First, he notes the Fed’s decision to ignore the growth of the housing bubble in the last decade. He said that they viewed the issue of financial stability as one appropriately left to regulators, not a concern for monetary policy. This is largely right, but it ignores the point that the Fed also has enormous regulatory power, including the responsibility for oversight on the issuance of mortgages.

Alan Greenspan essentially ignored these responsibilities, seeing them as inconsequential.This is largely because he didn’t see bubbles as any big deal, or at least this is what he publicly said in a speech he gave at the American Economics Association convention in January of 2004. In this speech he patted himself on the back for having the good sense to let the stock bubble run its course and then pick up the pieces after it burst. (The next day, Ben Bernanke, who was then a Fed governor, explained why it was necessary to still have a 1.0 percent federal funds rate, more than two years after the recession had officially ended. This suggested it was not easy to pick up the pieces.)

The other area where Mallaby is not exactly on target is in discussing the Fed’s tools. While he is correct in arguing that the Fed has more room to lower the federal funds rate in the context of a higher inflation rate, it is not right that this is its only tool. The Fed could target a long-term interest rate. For example, it could set a target of 1.0 percent for the 10-year Treasury rate for the next year.

This sort of targeting of a longer term rate would provide a more direct boost to growth than lowering the federal funds rate. While it might be desirable to rely on a more known tool for monetary policy, it is wrong to imply that there is nothing more the Fed can do to boost growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

One of the highest principles of the Republican Party is destroying Obamacare. It seems that the Republicans in Tennessee may be making a big step in that direction. According to the state’s insurance commissioner, the health care exchange in the state is on the edge of collapse. The number of insurers taking part in the exchange is down to four and the fees they charge are soaring.

That’s great news for people committed to keeping people in Tennessee from being able to get health care insurance. Of course, because of Obamacare, even if the exchange in Tennessee collapses, those who can afford to get insurance on their own will still be able to buy it in the individual market without regard to any pre-existing condition. That means that people with heart disease or cancer survivors will be able to get insurance for the same price as everyone else.

But since the subsidies for insurance are only available for people buying insurance on the exchange, if policies are not offered on the exchange, then Tennessee’s Republicans will have effectively denied the state’s citizens access to the same subsidies that people in every other state can get. Now that is a great accomplishment.

Of course it is not hard to fix the exchanges to make sure there are a substantial number of insurers offering policy. Suppose Tennessee required insurers to offer policies on the exchange as a condition of offering policies outside of the exchange.

The reason the exchanges face problems is that they are attracting a less healthy group of patients. The insurers naturally are happy to insure relatively healthy people — these people are mostly just sending the insurer a check every month. It’s the less healthy people who cause problems, they actually cost the insurers money. So, the state can just require that insurers commit to insuring less healthy people on the exchanges as a condition of insuring the more healthy people on the individual market.

That is one possible solution, there are others, if the point is to enable the people of Tennessee to buy health care insurance. But if the goal is to keep the people of Tennessee from being able to benefit from the Affordable Care Act then it sounds like the Republicans in Tennessee are doing a good job.

I suppose that’s good news for the rest of us, since we will be sending fewer of our tax dollars to Tennessee to pay for health care. I guess it means that people having trouble paying for insurance in Tennessee will have to move to a neighboring state like Kentucky, where the leadership has not been as effective in blocking people from getting health insurance.

One of the highest principles of the Republican Party is destroying Obamacare. It seems that the Republicans in Tennessee may be making a big step in that direction. According to the state’s insurance commissioner, the health care exchange in the state is on the edge of collapse. The number of insurers taking part in the exchange is down to four and the fees they charge are soaring.

That’s great news for people committed to keeping people in Tennessee from being able to get health care insurance. Of course, because of Obamacare, even if the exchange in Tennessee collapses, those who can afford to get insurance on their own will still be able to buy it in the individual market without regard to any pre-existing condition. That means that people with heart disease or cancer survivors will be able to get insurance for the same price as everyone else.

But since the subsidies for insurance are only available for people buying insurance on the exchange, if policies are not offered on the exchange, then Tennessee’s Republicans will have effectively denied the state’s citizens access to the same subsidies that people in every other state can get. Now that is a great accomplishment.

Of course it is not hard to fix the exchanges to make sure there are a substantial number of insurers offering policy. Suppose Tennessee required insurers to offer policies on the exchange as a condition of offering policies outside of the exchange.

The reason the exchanges face problems is that they are attracting a less healthy group of patients. The insurers naturally are happy to insure relatively healthy people — these people are mostly just sending the insurer a check every month. It’s the less healthy people who cause problems, they actually cost the insurers money. So, the state can just require that insurers commit to insuring less healthy people on the exchanges as a condition of insuring the more healthy people on the individual market.

That is one possible solution, there are others, if the point is to enable the people of Tennessee to buy health care insurance. But if the goal is to keep the people of Tennessee from being able to benefit from the Affordable Care Act then it sounds like the Republicans in Tennessee are doing a good job.

I suppose that’s good news for the rest of us, since we will be sending fewer of our tax dollars to Tennessee to pay for health care. I guess it means that people having trouble paying for insurance in Tennessee will have to move to a neighboring state like Kentucky, where the leadership has not been as effective in blocking people from getting health insurance.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Of course the NYT didn’t actually say this, instead it told readers:

“…the White House and congressional Republican leaders mostly agree on the economic benefits of trade.”

Actually, unless the paper has mind readers on staff, its reporters are not in a position to know whether the White House and Republican leaders have the same views on the economic benefits of trade or if they even have views on the economic benefits of trade. It is entirely possible that they are pushing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) out of a desire to ingratiate themselves with the powerful industries that stand to benefit from the deal. Since the NYT can only know what the White House and Republican leaders say, it would be best if they restrict their reporting to what they know to be true.

The piece also makes a point of noting a study by the footwear industry reporting that the TPP will save the country $4 billion on footwear. It would have been helpful to note that this figure is a projection of savings over the next ten years. The projected savings of $400 million a year comes to 0.0022 percent of GDP or roughly $3 a year per household. According to the study, the TPP will raise the deficit by $1.2 billion as a result of the lower tariffs on imported shoes. The other $2.8 billion in projected savings will come from lower wages and reduced profit in the retail and related industries.

Of course the NYT didn’t actually say this, instead it told readers:

“…the White House and congressional Republican leaders mostly agree on the economic benefits of trade.”

Actually, unless the paper has mind readers on staff, its reporters are not in a position to know whether the White House and Republican leaders have the same views on the economic benefits of trade or if they even have views on the economic benefits of trade. It is entirely possible that they are pushing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) out of a desire to ingratiate themselves with the powerful industries that stand to benefit from the deal. Since the NYT can only know what the White House and Republican leaders say, it would be best if they restrict their reporting to what they know to be true.

The piece also makes a point of noting a study by the footwear industry reporting that the TPP will save the country $4 billion on footwear. It would have been helpful to note that this figure is a projection of savings over the next ten years. The projected savings of $400 million a year comes to 0.0022 percent of GDP or roughly $3 a year per household. According to the study, the TPP will raise the deficit by $1.2 billion as a result of the lower tariffs on imported shoes. The other $2.8 billion in projected savings will come from lower wages and reduced profit in the retail and related industries.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ever since NAFTA passed in 1993, the media have been anxious to say how the pact has been a great boon to Mexico, even if its impact on the U.S. might not have been so great. Since Mexico’s growth post-NAFTA has actually been pathetic (the gap in per capita income with the United States has increased), the praise has often involved ignoring the data or even just making things up.

The Washington Post gets first prize in the latter category, famously telling readers back in 2007 that NAFTA had caused Mexico’s GDP to quadruple in the prior two decades. The actual figure according to the I.M.F. is 83 percent. The Post has never corrected this obvious error, indicating that when it comes to pushing its agenda on trade the Post has as much respect for the truth as Donald Trump.

Anyhow, the promotion of the post-NAFTA Mexican boom continues. The latest guilty party is the Los Angeles Times which devotes a lengthy piece to telling us how the boom is not just good for Mexico, but also the United States. Mexico’s per capita GDP growth since 2008 is less than 0.7 percent. This is a growth rate for a developing country that would more typically be described as “pathetic” than a boom.

Ever since NAFTA passed in 1993, the media have been anxious to say how the pact has been a great boon to Mexico, even if its impact on the U.S. might not have been so great. Since Mexico’s growth post-NAFTA has actually been pathetic (the gap in per capita income with the United States has increased), the praise has often involved ignoring the data or even just making things up.

The Washington Post gets first prize in the latter category, famously telling readers back in 2007 that NAFTA had caused Mexico’s GDP to quadruple in the prior two decades. The actual figure according to the I.M.F. is 83 percent. The Post has never corrected this obvious error, indicating that when it comes to pushing its agenda on trade the Post has as much respect for the truth as Donald Trump.

Anyhow, the promotion of the post-NAFTA Mexican boom continues. The latest guilty party is the Los Angeles Times which devotes a lengthy piece to telling us how the boom is not just good for Mexico, but also the United States. Mexico’s per capita GDP growth since 2008 is less than 0.7 percent. This is a growth rate for a developing country that would more typically be described as “pathetic” than a boom.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

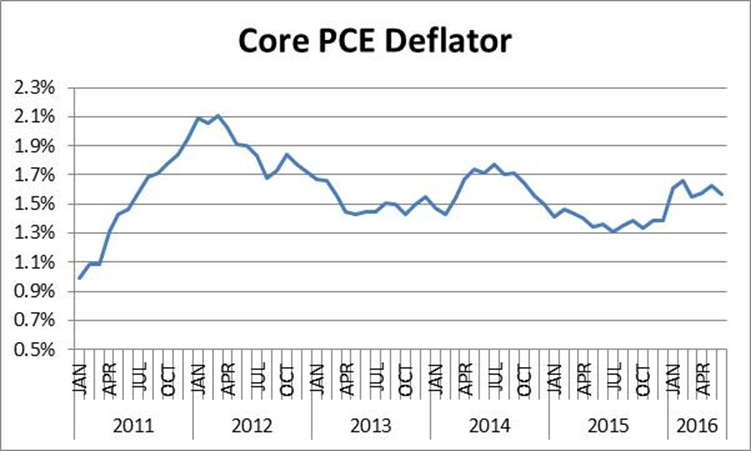

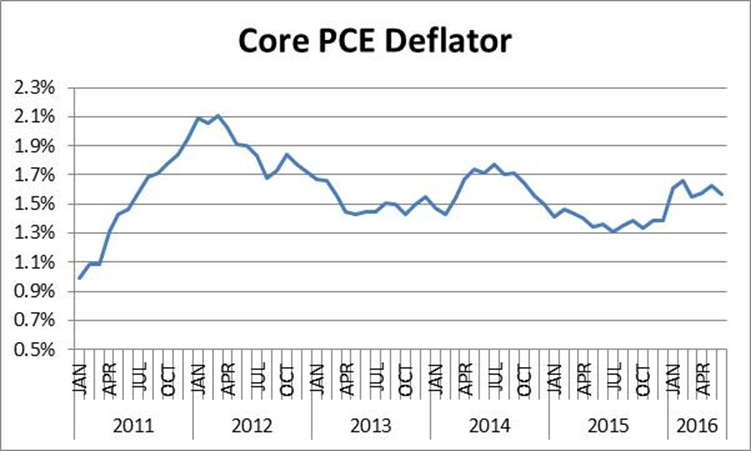

That seems to be the story according to MarketWatch. It quotes Stanley Fischer the vice-chair of the Federal Reserve Board as saying, “We are close to our targets” for inflation and unemployment. Fischer adds, that the current 1.6 percent inflation rate shown by the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator is “is within hailing distance” of the Fed’s 2.0 percent target.

Actually, this is not true. The 2.0 percent target was always identified as an average, not a ceiling. This means that periods of below 2.0 percent inflation should be averaged out with periods of above 2.0 percent inflation to reach the 2.0 percent target. If the Fed were sticking to prior policy, it should be looking to have an inflation rate somewhat above 2.0 percent for a number of years to offset the long period of below 2.0 percent inflation by this measure.

The figure below shows the year over year measure of the core inflation rate since the beginning of 2011. Not only has it been below 2.0 percent for the last four years, it shows no tendency to increase. Stanley Fischer is of course free to deviate from the Fed’s official target in his thinking, but it would have been appropriate to point that fact out. This makes it a much more newsworthy story. Of course, if the Fed does start raising rates the point is to slow the economy and limit the number of people who have jobs. That’s a big deal.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

That seems to be the story according to MarketWatch. It quotes Stanley Fischer the vice-chair of the Federal Reserve Board as saying, “We are close to our targets” for inflation and unemployment. Fischer adds, that the current 1.6 percent inflation rate shown by the core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator is “is within hailing distance” of the Fed’s 2.0 percent target.

Actually, this is not true. The 2.0 percent target was always identified as an average, not a ceiling. This means that periods of below 2.0 percent inflation should be averaged out with periods of above 2.0 percent inflation to reach the 2.0 percent target. If the Fed were sticking to prior policy, it should be looking to have an inflation rate somewhat above 2.0 percent for a number of years to offset the long period of below 2.0 percent inflation by this measure.

The figure below shows the year over year measure of the core inflation rate since the beginning of 2011. Not only has it been below 2.0 percent for the last four years, it shows no tendency to increase. Stanley Fischer is of course free to deviate from the Fed’s official target in his thinking, but it would have been appropriate to point that fact out. This makes it a much more newsworthy story. Of course, if the Fed does start raising rates the point is to slow the economy and limit the number of people who have jobs. That’s a big deal.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión