Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a piece on Puerto Rico’s financial problems which argued that they are a harbinger for the problems facing many state and local governments. In the process it managed to mix many different stories in a way that does not make much sense.

For example, it reported on the problems of deteriorating infrastructure in many cities and states, specifically citing the case of the troubled Metro transit system in Washington, DC. Infrastructure has historically been an area in which the federal government took substantial responsibility. Unfortunately, it has chosen not to step up its efforts in the last decade, even as the economy has been well below its full employment level of output. The decision by the federal government not to spend money cost the country hundreds of billions of dollars in lost output and needlessly kept millions of people from working. It also means that cities and states will face expensive repair bills and lost economic output in the future due to problems with infrastructure.

The piece also quoted former lieutenant governor Richard Ravitch saying, “New York City has $85 billion of retiree health obligations all by itself.” To put this in context, the city’s annual output is over $600 billion. Since this obligation will have to be met over the next three or four decades, Ravitch is referring to a commitment that is equal to roughly 0.5 percent of future income. This is hardly trivial, but not obviously an impossible burden.

The piece then refers to public pension funds in states like New Jersey and Illinois that are badly underfunded. In this context, it notes a warning from the Illinois Supreme Court from 1917 that the pension funds might run into trouble. The origins of these states’ current funding problem date to the stock bubble of the 1990s. They opted to put little or nothing into their pension funds as the stock market soared to record highs. Effectively, the rise in the market was making the contributions for them.

When the market crashed in 2000–2002, the pensions were suddenly much more poorly funded. However, the economy was also in a recession and state and local governments were squeezed for cash. Some, like Illinois and New Jersey, chose to forego part of their required contribution, perhaps in the hope that the stock bubble would return. It didn’t.

In any case, given the recent origins of the severe pension shortfalls in Illinois, New Jersey, and a few other states, it is probably fair to say that the 1917 warnings were wrong, unless the Court somehow foresaw the stock bubble and crash and its impact on pension funds.

The New York Times had a piece on Puerto Rico’s financial problems which argued that they are a harbinger for the problems facing many state and local governments. In the process it managed to mix many different stories in a way that does not make much sense.

For example, it reported on the problems of deteriorating infrastructure in many cities and states, specifically citing the case of the troubled Metro transit system in Washington, DC. Infrastructure has historically been an area in which the federal government took substantial responsibility. Unfortunately, it has chosen not to step up its efforts in the last decade, even as the economy has been well below its full employment level of output. The decision by the federal government not to spend money cost the country hundreds of billions of dollars in lost output and needlessly kept millions of people from working. It also means that cities and states will face expensive repair bills and lost economic output in the future due to problems with infrastructure.

The piece also quoted former lieutenant governor Richard Ravitch saying, “New York City has $85 billion of retiree health obligations all by itself.” To put this in context, the city’s annual output is over $600 billion. Since this obligation will have to be met over the next three or four decades, Ravitch is referring to a commitment that is equal to roughly 0.5 percent of future income. This is hardly trivial, but not obviously an impossible burden.

The piece then refers to public pension funds in states like New Jersey and Illinois that are badly underfunded. In this context, it notes a warning from the Illinois Supreme Court from 1917 that the pension funds might run into trouble. The origins of these states’ current funding problem date to the stock bubble of the 1990s. They opted to put little or nothing into their pension funds as the stock market soared to record highs. Effectively, the rise in the market was making the contributions for them.

When the market crashed in 2000–2002, the pensions were suddenly much more poorly funded. However, the economy was also in a recession and state and local governments were squeezed for cash. Some, like Illinois and New Jersey, chose to forego part of their required contribution, perhaps in the hope that the stock bubble would return. It didn’t.

In any case, given the recent origins of the severe pension shortfalls in Illinois, New Jersey, and a few other states, it is probably fair to say that the 1917 warnings were wrong, unless the Court somehow foresaw the stock bubble and crash and its impact on pension funds.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ruth Marcus used her column today to present the speech that House Speaker Paul Ryan should give to the Republican convention in order to disassociate himself from Donald Trump. She has Paul Ryan being somewhat less than honest.

Most notably, she wants Ryan to say:

“I have spent my life believing in, and fighting for, the ideals of the Republican Party: limited government, fiscal responsibility, free trade and free markets, the United States’ role as the world’s most important force for peace and liberty. It is not clear to me which, if any, of those convictions Mr. Trump shares.”

Ryan actually doesn’t want limited government, he actually wants pretty much no government. He has repeatedly introduced budgets that call for eliminating all of the federal government except Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and the military by 2050. His budgets provide zero funding for the Justice Department, the State Department, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the Education Department, the National Park Service and everything else we think of as the federal government.

As a big supporter of stronger and longer patent and copyright protection, it is hard to see how Ryan can claim to be a supporter of free trade and free markets. As far as fiscal responsibility, Ryan has proposed huge tax cuts that would go disproportionately to the wealthy, which he claims will be offset by ending deductions which he has never named.

She also has a reference to Social Security and Medicare, with Ryan then saying that he wants to “get entitlement spending under control.” If Ryan were being honest he would of course tell the convention that he wants to privatize both programs.

It’s not clear why Ms. Marcus thinks it’s appropriate for Ryan to misrepresent his fundamental political positions in this address to the Republican convention.

Ruth Marcus used her column today to present the speech that House Speaker Paul Ryan should give to the Republican convention in order to disassociate himself from Donald Trump. She has Paul Ryan being somewhat less than honest.

Most notably, she wants Ryan to say:

“I have spent my life believing in, and fighting for, the ideals of the Republican Party: limited government, fiscal responsibility, free trade and free markets, the United States’ role as the world’s most important force for peace and liberty. It is not clear to me which, if any, of those convictions Mr. Trump shares.”

Ryan actually doesn’t want limited government, he actually wants pretty much no government. He has repeatedly introduced budgets that call for eliminating all of the federal government except Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and the military by 2050. His budgets provide zero funding for the Justice Department, the State Department, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the Education Department, the National Park Service and everything else we think of as the federal government.

As a big supporter of stronger and longer patent and copyright protection, it is hard to see how Ryan can claim to be a supporter of free trade and free markets. As far as fiscal responsibility, Ryan has proposed huge tax cuts that would go disproportionately to the wealthy, which he claims will be offset by ending deductions which he has never named.

She also has a reference to Social Security and Medicare, with Ryan then saying that he wants to “get entitlement spending under control.” If Ryan were being honest he would of course tell the convention that he wants to privatize both programs.

It’s not clear why Ms. Marcus thinks it’s appropriate for Ryan to misrepresent his fundamental political positions in this address to the Republican convention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would seem to be the implication of an article warning about the economic consequences of lower birth rates. The piece notes the falloff in birth rates following the recession and points out that it has not recovered. It presents the prospect of fewer young people as a serious economic problem.

It, of course, is a serious problem if people feel that they are too financially insecure to have children; however, it is difficult to see any obvious economic problems resulting from that decision. A declining population means less pollution, less strain on the infrastructure, and lower priced housing. (Germany is held up as a horror story with its low birth rate. It is worth noting that housing costs have risen much less rapidly in Germany over the last two decades than in the United States.) If our children end up spending a smaller share of their income on housing costs than we do, this is not a problem.

That would seem to be the implication of an article warning about the economic consequences of lower birth rates. The piece notes the falloff in birth rates following the recession and points out that it has not recovered. It presents the prospect of fewer young people as a serious economic problem.

It, of course, is a serious problem if people feel that they are too financially insecure to have children; however, it is difficult to see any obvious economic problems resulting from that decision. A declining population means less pollution, less strain on the infrastructure, and lower priced housing. (Germany is held up as a horror story with its low birth rate. It is worth noting that housing costs have risen much less rapidly in Germany over the last two decades than in the United States.) If our children end up spending a smaller share of their income on housing costs than we do, this is not a problem.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

All Things Considered got things badly wrong in talking about the government debt last night. As most folks know, Donald Trump seemed to imply that he would threaten to default on the debt in order to force creditors to take write-downs on their bonds. He then clarified what he meant, saying that if interest rates rise, he would look to buy back government bonds at a discount.

For some reason, this left NPR befuddled:

“It’s not clear how that would work, though, since the cash-strapped government would have to borrow more money at rising interest rates to buy back its old debt. Holtz-Eakin was left scratching his head.”

It’s actually very clear how this would work. The government would borrow money at higher interest rates (it doesn’t matter if interest rates are rising), to buy back bonds whose market value is less than their nominal value. This is a very simple story, when interest rates rise, the market rise of bonds already issued falls. This would allow the government to reduce the nominal value of its outstanding debt, even if it doesn’t reduce its interest burden.

If it seems strange to people that the government would care about reducing the nominal value of its debt, then they haven’t been paying attention to policy debates in Washington over the last decade. There has been a huge amount of energy devoted to keeping down the debt-to-GDP ratio. In fact, there was a widely held view in policy circles that if the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 90 percent, then the economy would face a prolonged period of slow growth. This view was first espoused by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, two prominent Harvard professors. It was frequently referenced in publications like the New York Times, Washington Post, and undoubtedly mentioned on NPR. It was also a main justification for the budget cuts put in place in 2011.

The numerator in this debt-to-GDP ratio is the nominal debt, the number that could be reduced by exactly the sort of financial engineering that Donald Trump proposed. For this reason it is difficult to understand why Trump’s proposal would have left Douglas Holtz-Eakin (a former head of the Congressional Budget Office and chief economist for George W. Bush) scratching his head.

Of course it is silly to be worried about the ratio of nominal debt to GDP, but that can’t erase the fact that this ratio has been a central concern in policy circles for some time. It doesn’t speak well of our media that they only recognize that the debt-to-GDP ratio doesn’t matter when the point is raised by Donald Trump, but not when it is raised by elite economists and top policy makers. (Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson frequently made reference to the 90 percent figure when they chaired President Obama’s deficit commission.)

What matters much more than the ratio of debt to GDP is the ratio of interest payments to GDP. If we net out the interest refunded by the Federal Reserve Board, this ratio now stands at 0.8 percent of GDP. By comparison, it was more than 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s. These numbers don’t fit the deficit crisis story widely preached in the media, but if we want to get serious, that would be the number to focus on.

Addendum:

In case you were wondering how anyone could be concerned about the ratio of nominal debt to GDP, here is NPR on the topic back in 2011.

All Things Considered got things badly wrong in talking about the government debt last night. As most folks know, Donald Trump seemed to imply that he would threaten to default on the debt in order to force creditors to take write-downs on their bonds. He then clarified what he meant, saying that if interest rates rise, he would look to buy back government bonds at a discount.

For some reason, this left NPR befuddled:

“It’s not clear how that would work, though, since the cash-strapped government would have to borrow more money at rising interest rates to buy back its old debt. Holtz-Eakin was left scratching his head.”

It’s actually very clear how this would work. The government would borrow money at higher interest rates (it doesn’t matter if interest rates are rising), to buy back bonds whose market value is less than their nominal value. This is a very simple story, when interest rates rise, the market rise of bonds already issued falls. This would allow the government to reduce the nominal value of its outstanding debt, even if it doesn’t reduce its interest burden.

If it seems strange to people that the government would care about reducing the nominal value of its debt, then they haven’t been paying attention to policy debates in Washington over the last decade. There has been a huge amount of energy devoted to keeping down the debt-to-GDP ratio. In fact, there was a widely held view in policy circles that if the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 90 percent, then the economy would face a prolonged period of slow growth. This view was first espoused by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, two prominent Harvard professors. It was frequently referenced in publications like the New York Times, Washington Post, and undoubtedly mentioned on NPR. It was also a main justification for the budget cuts put in place in 2011.

The numerator in this debt-to-GDP ratio is the nominal debt, the number that could be reduced by exactly the sort of financial engineering that Donald Trump proposed. For this reason it is difficult to understand why Trump’s proposal would have left Douglas Holtz-Eakin (a former head of the Congressional Budget Office and chief economist for George W. Bush) scratching his head.

Of course it is silly to be worried about the ratio of nominal debt to GDP, but that can’t erase the fact that this ratio has been a central concern in policy circles for some time. It doesn’t speak well of our media that they only recognize that the debt-to-GDP ratio doesn’t matter when the point is raised by Donald Trump, but not when it is raised by elite economists and top policy makers. (Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson frequently made reference to the 90 percent figure when they chaired President Obama’s deficit commission.)

What matters much more than the ratio of debt to GDP is the ratio of interest payments to GDP. If we net out the interest refunded by the Federal Reserve Board, this ratio now stands at 0.8 percent of GDP. By comparison, it was more than 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s. These numbers don’t fit the deficit crisis story widely preached in the media, but if we want to get serious, that would be the number to focus on.

Addendum:

In case you were wondering how anyone could be concerned about the ratio of nominal debt to GDP, here is NPR on the topic back in 2011.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

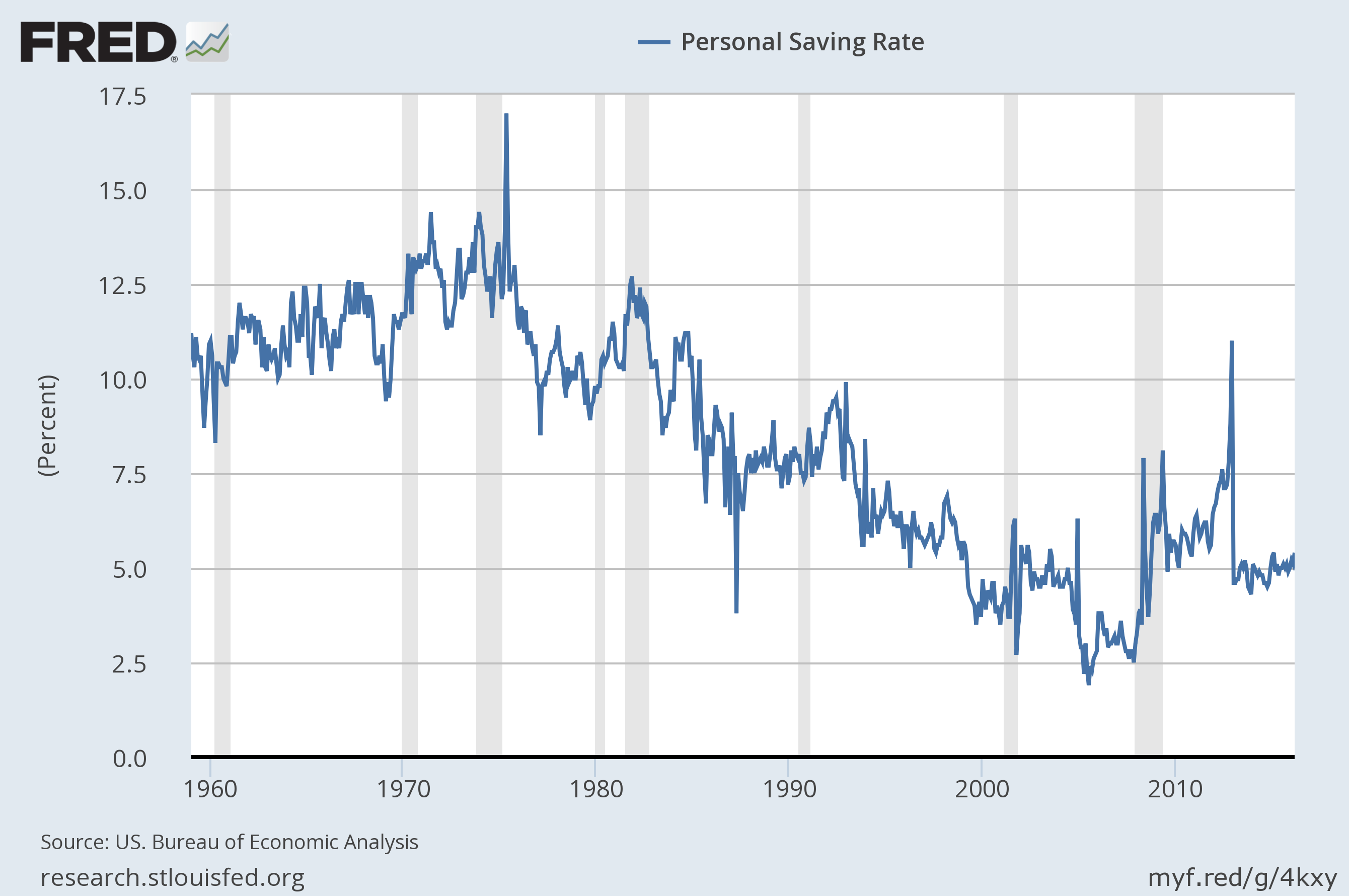

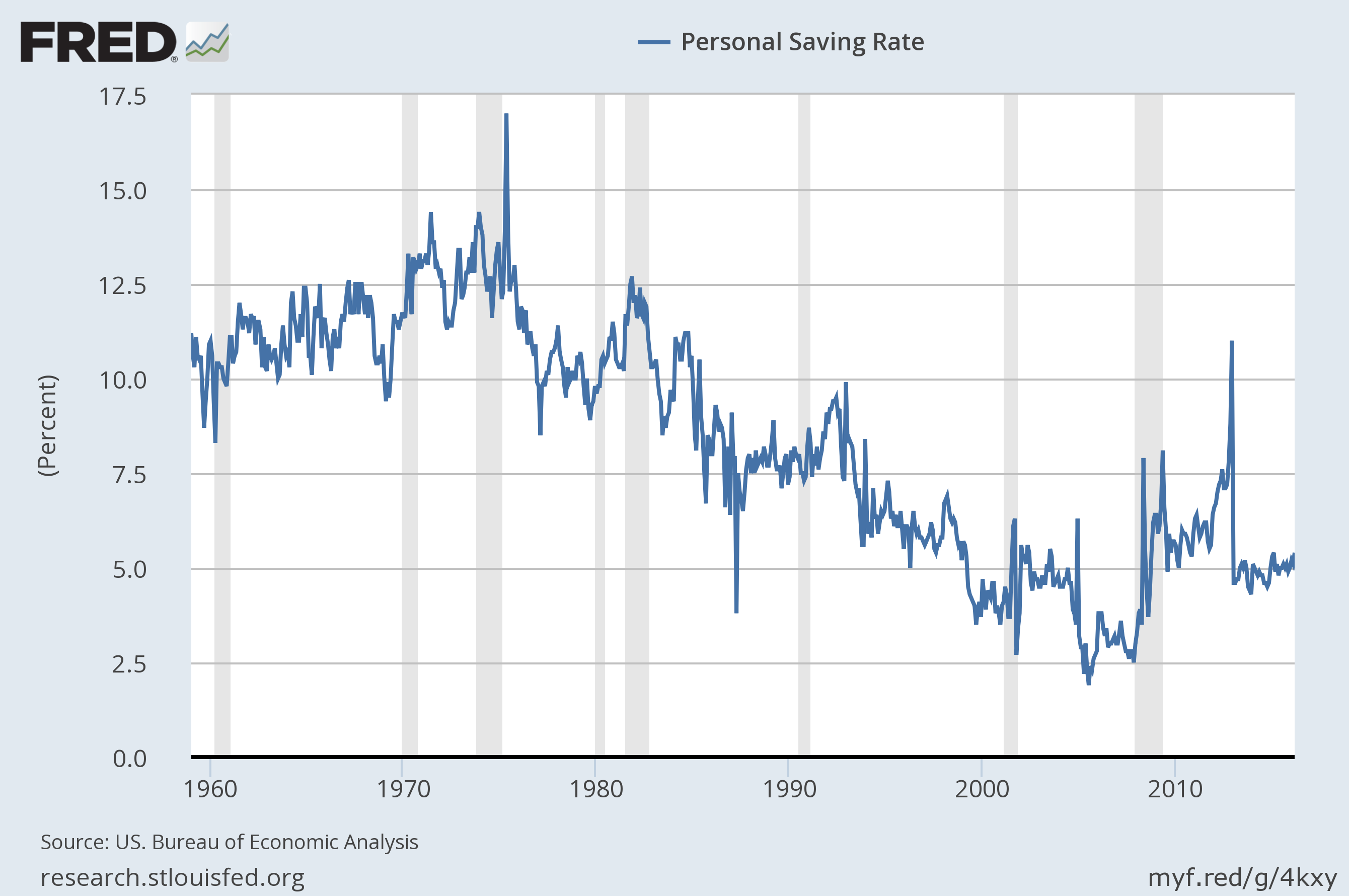

It really is amazing what you can find in the Washington Post’s opinion pages. The latest is Robert Samuelson complaining that the problem with the weak recovery is that people are saving too much. This is amazing for two reasons: first, it is not true, and second if people saved less they would have even less money to support themselves in retirement.

Starting with the first point, the saving rate is actually quite low by historical standards. It is just over 5.0 percent. The only periods in which it was lower was when the wealth generated by the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade pushed the saving rate somewhat lower. For most of the 1960s and 1970s it was over 10.0 percent. Even in the 1980s it averaged more than 7.0 percent. (No, there should not be a downward trend in saving rates, unless you think that people will eventually have zero money in retirement.)

If we want to see the origins of the economy’s shortfall of demand, the trade deficit is the obvious place to look. If the trade deficit was 1.0 percent of GDP, as opposed to its current 3.0 percent of GDP, this would have the same impact on demand as a drop in the savings rate of 2.5 percentage points. The standard route for getting a lower trade deficit is a lower valued dollar, but apparently no one is supposed to make this point in the Washington Post’s opinion pages. (The savings rate is likely overstated at present. There is a large gap between the income side measure of GDP and the output side. This likely reflects some amount of capital gains wrongly being recorded as ordinary income. If income is overstated, it would cause the reported savings rate to be higher than the true saving rate.)

The other reason why the complaint about excessive savings is bizarre is that Samuelson, like most of the rest of his colleagues in the opinion section, regularly calls for cutting Social Security and Medicare. So apparently Samuelson both wants retirees to have less personal savings to support themselves at the same time they have less support from public social insurance programs: only in the Washington Post.

It really is amazing what you can find in the Washington Post’s opinion pages. The latest is Robert Samuelson complaining that the problem with the weak recovery is that people are saving too much. This is amazing for two reasons: first, it is not true, and second if people saved less they would have even less money to support themselves in retirement.

Starting with the first point, the saving rate is actually quite low by historical standards. It is just over 5.0 percent. The only periods in which it was lower was when the wealth generated by the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade pushed the saving rate somewhat lower. For most of the 1960s and 1970s it was over 10.0 percent. Even in the 1980s it averaged more than 7.0 percent. (No, there should not be a downward trend in saving rates, unless you think that people will eventually have zero money in retirement.)

If we want to see the origins of the economy’s shortfall of demand, the trade deficit is the obvious place to look. If the trade deficit was 1.0 percent of GDP, as opposed to its current 3.0 percent of GDP, this would have the same impact on demand as a drop in the savings rate of 2.5 percentage points. The standard route for getting a lower trade deficit is a lower valued dollar, but apparently no one is supposed to make this point in the Washington Post’s opinion pages. (The savings rate is likely overstated at present. There is a large gap between the income side measure of GDP and the output side. This likely reflects some amount of capital gains wrongly being recorded as ordinary income. If income is overstated, it would cause the reported savings rate to be higher than the true saving rate.)

The other reason why the complaint about excessive savings is bizarre is that Samuelson, like most of the rest of his colleagues in the opinion section, regularly calls for cutting Social Security and Medicare. So apparently Samuelson both wants retirees to have less personal savings to support themselves at the same time they have less support from public social insurance programs: only in the Washington Post.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I guess we can get a pretty good sense of the priorities of the folks at ABC News from the headline of a piece on the costs of replacing the country’s lead water pipes. The headline noted the price for Flint and then warned of the “colossal price tag for a US-wide remedy.”

The piece gives two estimates of the cost. One puts the costs at between a few billion dollars and fifty billion dollars. The other puts it at $30 billion. If we take the latter figure and assume that the pipes will be replaced over the next decade, the cost would come to roughly 0.025 percent of GDP. (GDP will average roughly $20 trillion, in 2016 dollars, over the next decade.)

To give some points of comparison, we spend roughly 3.5 percent of GDP on the military. Patent protection for prescription drugs raise their cost by close to 2.0 percent of GDP. And, protected our doctors from international competition raises our annual health care bill by 0.5 percent of GDP.

Note: An earlier version wrongly put average GDP over the next decade at $20 billion.

I guess we can get a pretty good sense of the priorities of the folks at ABC News from the headline of a piece on the costs of replacing the country’s lead water pipes. The headline noted the price for Flint and then warned of the “colossal price tag for a US-wide remedy.”

The piece gives two estimates of the cost. One puts the costs at between a few billion dollars and fifty billion dollars. The other puts it at $30 billion. If we take the latter figure and assume that the pipes will be replaced over the next decade, the cost would come to roughly 0.025 percent of GDP. (GDP will average roughly $20 trillion, in 2016 dollars, over the next decade.)

To give some points of comparison, we spend roughly 3.5 percent of GDP on the military. Patent protection for prescription drugs raise their cost by close to 2.0 percent of GDP. And, protected our doctors from international competition raises our annual health care bill by 0.5 percent of GDP.

Note: An earlier version wrongly put average GDP over the next decade at $20 billion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As the media erupt in fury over Donald Trump’s comments on the debt, it is worth taking the opportunity to remind people that the interest burden on the national debt is near a post-World War II low. While the debt-to-GDP ratio rose sharply in the Great Recession, because interest rates are extremely low, we face an unusually low interest burden.

This fact has largely been missing from reporting on the issue. For example a Washington Post piece warning of the end of the world if Trump tried to negotiate on the debt, told readers that the government would pay roughly $255 billion this year in interest on the debt. This includes the $113 billion that the Federal Reserve Board will receive and refund back to the Treasury. That leaves a net interest burden of $142 billion, a bit less than 0.8 percent of GDP. By comparison, the interest burden was over 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s.

It is also worth noting that we actually could buy back debt at a discount if interest rates rose. When interest rates rise, the market value of long-term debt falls. This means that the government could issue new debt, which would pay a higher interest rate, to buy back debt with a higher face value, thereby reducing its debt, but leaving its interest burden unchanged.

There is no economic reason to do this sort of financial engineering, but there are people who worry about debt to GDP ratios apart from the interest burden, like Harvard economics professors, the Washington Post editorial page writers, and Washington budget wonks. As a result, this sort of financial engineering may be a useful way to alleviate concerns on the debt and free up public money for productive uses.

As the media erupt in fury over Donald Trump’s comments on the debt, it is worth taking the opportunity to remind people that the interest burden on the national debt is near a post-World War II low. While the debt-to-GDP ratio rose sharply in the Great Recession, because interest rates are extremely low, we face an unusually low interest burden.

This fact has largely been missing from reporting on the issue. For example a Washington Post piece warning of the end of the world if Trump tried to negotiate on the debt, told readers that the government would pay roughly $255 billion this year in interest on the debt. This includes the $113 billion that the Federal Reserve Board will receive and refund back to the Treasury. That leaves a net interest burden of $142 billion, a bit less than 0.8 percent of GDP. By comparison, the interest burden was over 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s.

It is also worth noting that we actually could buy back debt at a discount if interest rates rose. When interest rates rise, the market value of long-term debt falls. This means that the government could issue new debt, which would pay a higher interest rate, to buy back debt with a higher face value, thereby reducing its debt, but leaving its interest burden unchanged.

There is no economic reason to do this sort of financial engineering, but there are people who worry about debt to GDP ratios apart from the interest burden, like Harvard economics professors, the Washington Post editorial page writers, and Washington budget wonks. As a result, this sort of financial engineering may be a useful way to alleviate concerns on the debt and free up public money for productive uses.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión