The NYT had a column by Jim Parrot and Mark Zandi on reforming Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. (Jim Parrott is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and the owner of Falling Creek Advisors, a financial consulting firm. Mark Zandi is the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.) The article argues that the problem with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was that they were considered too big to fail. It therefore puts forward the case for ending their monopoly on issuing government guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

This argument seriously misrepresents the issues with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The real problem was that they issued trillions of dollars in MBS that were implicitly backed up by the government. At the time they failed in the summer of 2008, the generally held view in financial circles was that the government would be obligated to honor their MBS regardless of whether or not it kept Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in business. In other words, the issue was not the $180 billion bailout (about which elite types routinely and misleadingly say we made a profit) the issue was the huge amount of bad MBS that helped propel the housing bubble.

This was a direct result of the perverse incentives created by a system where private shareholders and top executives stood to profit by passing risk off to the government. This incentive does not exist today. This incentive does not exist today. (The line is repeated because policy folks have a hard time understanding it.) As long as Fannie and Freddie are essentially public companies, that do not offer high returns to shareholders and pay outlandish salaries to CEOs, no one has incentive to take excessive risks.

This changes if we allow private banks to issue mortgage backed securities with the guarantee of the government. This would mean that Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and the rest would be able to issue the same sort of subprime MBS they did in the bubble years with assurance that even in a worst case scenario the government would reimbursement investors for almost the full value of their investment. This is a great recipe for pumping up financial sector profits and another housing bubble. It does not make sense as public policy.

Addendum

This piece provides some background on the most likely reform of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The NYT had a column by Jim Parrot and Mark Zandi on reforming Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. (Jim Parrott is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and the owner of Falling Creek Advisors, a financial consulting firm. Mark Zandi is the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.) The article argues that the problem with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was that they were considered too big to fail. It therefore puts forward the case for ending their monopoly on issuing government guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

This argument seriously misrepresents the issues with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The real problem was that they issued trillions of dollars in MBS that were implicitly backed up by the government. At the time they failed in the summer of 2008, the generally held view in financial circles was that the government would be obligated to honor their MBS regardless of whether or not it kept Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in business. In other words, the issue was not the $180 billion bailout (about which elite types routinely and misleadingly say we made a profit) the issue was the huge amount of bad MBS that helped propel the housing bubble.

This was a direct result of the perverse incentives created by a system where private shareholders and top executives stood to profit by passing risk off to the government. This incentive does not exist today. This incentive does not exist today. (The line is repeated because policy folks have a hard time understanding it.) As long as Fannie and Freddie are essentially public companies, that do not offer high returns to shareholders and pay outlandish salaries to CEOs, no one has incentive to take excessive risks.

This changes if we allow private banks to issue mortgage backed securities with the guarantee of the government. This would mean that Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and the rest would be able to issue the same sort of subprime MBS they did in the bubble years with assurance that even in a worst case scenario the government would reimbursement investors for almost the full value of their investment. This is a great recipe for pumping up financial sector profits and another housing bubble. It does not make sense as public policy.

Addendum

This piece provides some background on the most likely reform of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson again gives us his data free explanation for the weak recovery in his Monday column. He contrasts the current weak recovery with the strong recovery of the eighties. He notes the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy in both periods, then tells readers:

“In the 1980s and ’90s, consumers and businesses were eager to spend. The Fed accommodated that demand but did not create it. By contrast, consumers and businesses now are conditioned to be wary. Having lived through events — the financial panic and crushing recession — that supposedly could not happen, they are reluctant spenders. The Fed can try to ease their caution but cannot systematically eliminate it.”

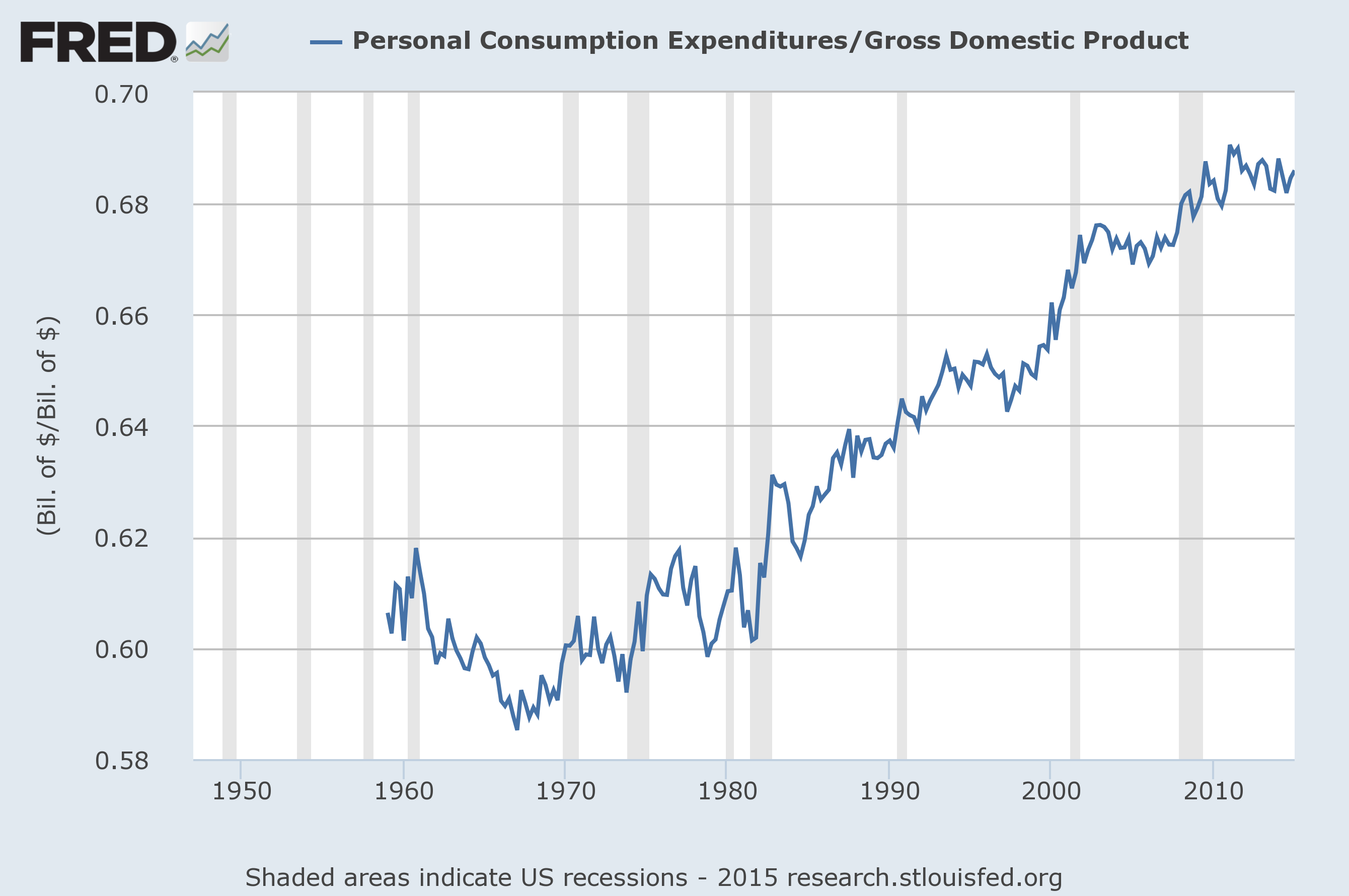

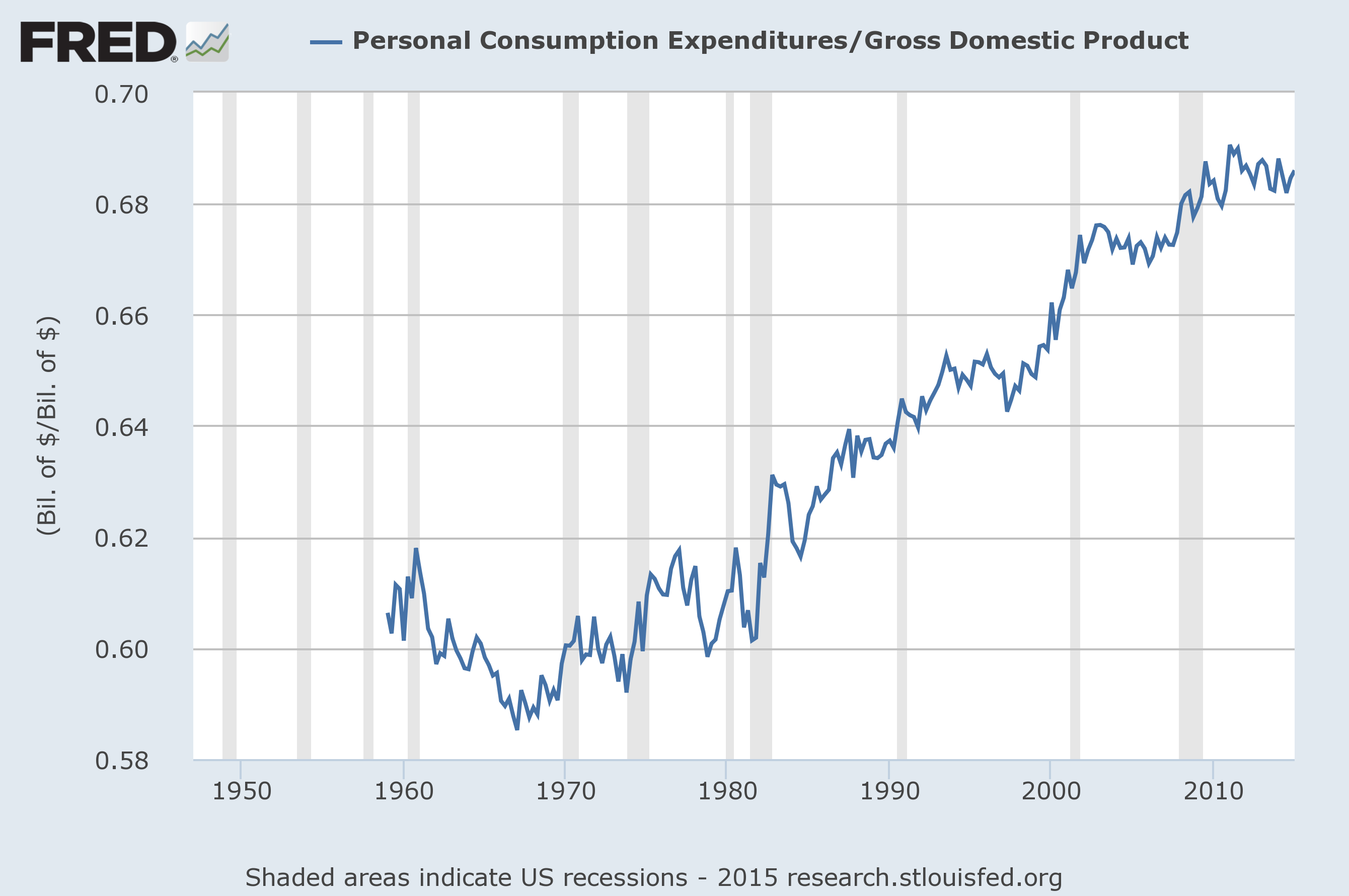

The problem with this story is that consumers are spending and businesses are investing. Consumption is at a near record high as a share of GDP. It is only slightly below the peak reached in the housing bubble.

Non-residential investment as a share of GDP is somewhat below the peaks of the tech bubble in the late 1990s, but is higher than during the eighties boom. The explanation for the weaker recovery is that there was an enormous excess supply of housing coming out of the bubble. This kept construction rates very low ever since the collapse of the bubble. By contrast, the Volcker recession led to a plunge in housing construction, which created a huge amount of pent-up demand for when the Fed lowered interest rates. (The trade deficit, at 3.0 percent of GDP or $500 billion annually, also creates a huge hole in demand that is not easily filled.)

The other major difference between the current recovery and the 1980s was that the structural budget deficit was expanding rapidly in that recovery. In the current recovery it has been contracting rapidly.

In short, there is a very simple story as to why this recovery has been weak and has nothing to do with the factors that Samuelson keeps highlighting.

Robert Samuelson again gives us his data free explanation for the weak recovery in his Monday column. He contrasts the current weak recovery with the strong recovery of the eighties. He notes the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy in both periods, then tells readers:

“In the 1980s and ’90s, consumers and businesses were eager to spend. The Fed accommodated that demand but did not create it. By contrast, consumers and businesses now are conditioned to be wary. Having lived through events — the financial panic and crushing recession — that supposedly could not happen, they are reluctant spenders. The Fed can try to ease their caution but cannot systematically eliminate it.”

The problem with this story is that consumers are spending and businesses are investing. Consumption is at a near record high as a share of GDP. It is only slightly below the peak reached in the housing bubble.

Non-residential investment as a share of GDP is somewhat below the peaks of the tech bubble in the late 1990s, but is higher than during the eighties boom. The explanation for the weaker recovery is that there was an enormous excess supply of housing coming out of the bubble. This kept construction rates very low ever since the collapse of the bubble. By contrast, the Volcker recession led to a plunge in housing construction, which created a huge amount of pent-up demand for when the Fed lowered interest rates. (The trade deficit, at 3.0 percent of GDP or $500 billion annually, also creates a huge hole in demand that is not easily filled.)

The other major difference between the current recovery and the 1980s was that the structural budget deficit was expanding rapidly in that recovery. In the current recovery it has been contracting rapidly.

In short, there is a very simple story as to why this recovery has been weak and has nothing to do with the factors that Samuelson keeps highlighting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In case you were wondering about the importance of a $100 billion a year, non-binding commitment, it’s roughly 0.25 percent of rich countries’ $40 trillion annual GDP (about 6 percent of what the U.S. spends on the military). This counts the U.S., European Union, Japan, Canada, and Australia as rich countries. If China is included in that list, the commitment would be less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

Addendum

I see my comment on military spending here created a bit of confusion. I was looking at the U.S. share of the commitment, 0.25 percent of its GDP and comparing it to the roughly 4.0 percent of GDP it spends on the military. That comes to 6 percent. I was not referring to the whole $100 billion.

In case you were wondering about the importance of a $100 billion a year, non-binding commitment, it’s roughly 0.25 percent of rich countries’ $40 trillion annual GDP (about 6 percent of what the U.S. spends on the military). This counts the U.S., European Union, Japan, Canada, and Australia as rich countries. If China is included in that list, the commitment would be less than 0.2 percent of GDP.

Addendum

I see my comment on military spending here created a bit of confusion. I was looking at the U.S. share of the commitment, 0.25 percent of its GDP and comparing it to the roughly 4.0 percent of GDP it spends on the military. That comes to 6 percent. I was not referring to the whole $100 billion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, this one is a bit personal, but it reflects a larger issue. The Pew Research Center just put out a study showing that a declining share of the U.S. population is middle class, with greater percentages falling both in the upper and lower income category than was the case four decades ago. Washington Post columnist Dan Balz touted this declining middle class story as an explanation for the rise of Donald Trump.

The problem here is that there is nothing new in the Pew study. My friend and former boss, Larry Mishel, has been writing about wage stagnation for a quarter century at the Economic Policy Institute. The biannual volume, The State of Working America, has been tracking the pattern of stagnating middle class wages and family income (for the non-elderly middle class, income is wages) since 1990.

The Pew study added nothing new to this research. They simply constructed an arbitrary definition of middle class and found that fewer families fall within it.

Perhaps having a high budget “centrist” outfit like Pew tout this finding is the only way to get a centrist Washington Post columnist like Balz to pay attention, but it is a bit annoying when we see someone touted for discovering what was already well-known. Oh well, at least it creates good-paying jobs for people without discernible skills.

Okay, this one is a bit personal, but it reflects a larger issue. The Pew Research Center just put out a study showing that a declining share of the U.S. population is middle class, with greater percentages falling both in the upper and lower income category than was the case four decades ago. Washington Post columnist Dan Balz touted this declining middle class story as an explanation for the rise of Donald Trump.

The problem here is that there is nothing new in the Pew study. My friend and former boss, Larry Mishel, has been writing about wage stagnation for a quarter century at the Economic Policy Institute. The biannual volume, The State of Working America, has been tracking the pattern of stagnating middle class wages and family income (for the non-elderly middle class, income is wages) since 1990.

The Pew study added nothing new to this research. They simply constructed an arbitrary definition of middle class and found that fewer families fall within it.

Perhaps having a high budget “centrist” outfit like Pew tout this finding is the only way to get a centrist Washington Post columnist like Balz to pay attention, but it is a bit annoying when we see someone touted for discovering what was already well-known. Oh well, at least it creates good-paying jobs for people without discernible skills.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Krugman comments that Portugal can be a situation where its aging population, combined with a large outflow of younger people due to high unemployment, can lead to an ever worsening financial situation where fewer workers are left to support a larger debt and non-working population. (Note, the key factor here is the migration, not the aging.)

That pretty well describes the picture with Puerto Rico, with a large segment of its working age population moving to the mainland United States, leaving the island with relatively few working people to provide taxable income. The upside for Puerto Rico is that at least it has benefits like Social Security and Medicare covered by the national government, compared with Portugal, which must pay for its equivalents from its own tax revenue.

Paul Krugman comments that Portugal can be a situation where its aging population, combined with a large outflow of younger people due to high unemployment, can lead to an ever worsening financial situation where fewer workers are left to support a larger debt and non-working population. (Note, the key factor here is the migration, not the aging.)

That pretty well describes the picture with Puerto Rico, with a large segment of its working age population moving to the mainland United States, leaving the island with relatively few working people to provide taxable income. The upside for Puerto Rico is that at least it has benefits like Social Security and Medicare covered by the national government, compared with Portugal, which must pay for its equivalents from its own tax revenue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article reporting on the fact that the vast majority of people in Kentucky want the state to leave in place its expansion of the state’s Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), even though it just elected a governor who is strongly opposed to the ACA. The piece notes that 425,000 people in the state (just under 10 percent of the population) have signed up for Medicaid, then adds “by contrast, only 89,000 people have bought private coverage through Kynect, the state’s health care exchange.”

It is important to note that people phase in and out of the exchanges, in large part due to changing employment patterns. Roughly 3.0 percent of the workforce lose or leave their jobs every month. This means many people who had health care insurance may lose it or many who don’t have it may acquire it, as they change jobs. This means that the number of people who had insurance through the exchanges at some point over the last two years is likely far larger than the number currently on the exchanges.

The NYT had an article reporting on the fact that the vast majority of people in Kentucky want the state to leave in place its expansion of the state’s Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), even though it just elected a governor who is strongly opposed to the ACA. The piece notes that 425,000 people in the state (just under 10 percent of the population) have signed up for Medicaid, then adds “by contrast, only 89,000 people have bought private coverage through Kynect, the state’s health care exchange.”

It is important to note that people phase in and out of the exchanges, in large part due to changing employment patterns. Roughly 3.0 percent of the workforce lose or leave their jobs every month. This means many people who had health care insurance may lose it or many who don’t have it may acquire it, as they change jobs. This means that the number of people who had insurance through the exchanges at some point over the last two years is likely far larger than the number currently on the exchanges.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New Yorker ran a rather confused piece by Gary Sernovitz, a managing director at the investment firm Lime Rock Partners, on whether Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton would be more effective in reining in Wall Street. The piece assures us that Secretary Clinton has a better understanding of Wall Street and that her plan would be more effective in cracking down on the industry. The piece is bizarre both because it essentially dismisses the concern with too big to fail banks and completely ignores Sanders’ proposal for a financial transactions tax, which is by far the most important mechanism for reining in the financial industry.

The piece assures us that too big to fail banks are no longer a problem, noting their drop in profitability from bubble peaks and telling readers:

“…not only are Sanders’s bogeybanks just one part of Wall Street but they are getting less powerful and less problematic by the year.”

This argument is strange for a couple of reasons. First, the peak of the subprime bubble frenzy is hardly a good base of comparison. The real question is should we anticipate declining profits going forward. That hardly seems clear. For example, Citigroup recently reported surging profits, while Wells Fargo’s third quarter profits were up 8 percent from 2014 levels.

If Sernovitz is predicting that the big banks are about to shrivel up to nothingness, the market does not agree with him. Citigroup has a market capitalization of $152 billion, JPMorgan has a market cap of $236 billion, and Bank of America has a market cap of $174 billion. Clearly investors agree with Sanders in thinking that these huge banks will have sizable profits for some time to come.

The real question on too big to fail is whether the government would sit by and let a Goldman Sachs or Citigroup go bankrupt. Perhaps some people think that it is now the case, but I’ve never met anyone in that group.

Sernovitz is also dismissive on Sanders call for bringing back the Glass-Steagall separation between commercial banking and investment banking. He makes the comparison to the battle over the Keystone XL pipeline, which is actually quite appropriate. The Keystone battle did take on exaggerated importance in the climate debate. There was never a zero/one proposition in which no tar sands oil would be pumped without the pipeline, while all of it would be pumped if the pipeline was constructed. Nonetheless, if the Obama administration was committed to restricting greenhouse gas emissions, it is difficult to see why it would support the building of a pipeline that would facilitate bringing some of the world’s dirtiest oil to market.

In the same vein, Sernovitz is right that it is difficult to see how anything about the growth of the housing bubble and its subsequent collapse would have been very different if Glass-Steagall were still in place. And, it is possible in principle to regulate bank’s risky practices without Glass-Steagall, as the Volcker rule is doing. However, enforcement tends to weaken over time under industry pressure, which is a reason why the clear lines of Glass-Steagall can be beneficial. Furthermore, as with Keystone, if we want to restrict banks’ power, what is the advantage of letting them get bigger and more complex?

The repeal of Glass-Steagall was sold in large part by boasting of the potential synergies from combining investment and commercial banking under one roof. But if the operations are kept completely separate, as is supposed to be the case, where are the synergies?

But the strangest part of Sernovitz’s story is that he leaves out Sanders’ financial transactions tax (FTT) altogether. This is bizarre, because the FTT is essentially a hatchet blow to the waste and exorbitant salaries in the industry.

Most research shows that trading volume is very responsive to the cost of trading, with most estimates putting the elasticity close to one. This means that if trading costs rise by 50 percent, then trading volume declines by 50 percent. (In its recent analysis of FTTs, the Tax Policy Center assumed that the elasticity was 1.5, meaning that trading volume decline by 150 percent of the increase in trading costs.) The implication of this finding is that the financial industry would pay the full cost of a financial transactions tax in the form of reduced trading revenue.

The Tax Policy Center estimated that a 0.1 percent tax on stock trades, scaled with lower taxes on other assets, would raise $50 billion a year in tax revenue. The implied reduction in trading revenue was even larger. Senator Sanders has proposed a tax of 0.5 percent on equities (also with a scaled tax on other assets). This would lead to an even larger reduction in revenue for the financial industry.

It is incredible that Sernovitz would ignore a policy with such enormous consequences for the financial sector in his assessment of which candidate would be tougher on Wall Street. Sanders FTT would almost certainly do more to change behavior on Wall Street than everything that Clinton has proposed taken together, by a rather large margin. Leaving out the FTT in this comparison is sort of like evaluating the New England Patriots’ Super Bowl prospects without discussing their quarterback.

The New Yorker ran a rather confused piece by Gary Sernovitz, a managing director at the investment firm Lime Rock Partners, on whether Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton would be more effective in reining in Wall Street. The piece assures us that Secretary Clinton has a better understanding of Wall Street and that her plan would be more effective in cracking down on the industry. The piece is bizarre both because it essentially dismisses the concern with too big to fail banks and completely ignores Sanders’ proposal for a financial transactions tax, which is by far the most important mechanism for reining in the financial industry.

The piece assures us that too big to fail banks are no longer a problem, noting their drop in profitability from bubble peaks and telling readers:

“…not only are Sanders’s bogeybanks just one part of Wall Street but they are getting less powerful and less problematic by the year.”

This argument is strange for a couple of reasons. First, the peak of the subprime bubble frenzy is hardly a good base of comparison. The real question is should we anticipate declining profits going forward. That hardly seems clear. For example, Citigroup recently reported surging profits, while Wells Fargo’s third quarter profits were up 8 percent from 2014 levels.

If Sernovitz is predicting that the big banks are about to shrivel up to nothingness, the market does not agree with him. Citigroup has a market capitalization of $152 billion, JPMorgan has a market cap of $236 billion, and Bank of America has a market cap of $174 billion. Clearly investors agree with Sanders in thinking that these huge banks will have sizable profits for some time to come.

The real question on too big to fail is whether the government would sit by and let a Goldman Sachs or Citigroup go bankrupt. Perhaps some people think that it is now the case, but I’ve never met anyone in that group.

Sernovitz is also dismissive on Sanders call for bringing back the Glass-Steagall separation between commercial banking and investment banking. He makes the comparison to the battle over the Keystone XL pipeline, which is actually quite appropriate. The Keystone battle did take on exaggerated importance in the climate debate. There was never a zero/one proposition in which no tar sands oil would be pumped without the pipeline, while all of it would be pumped if the pipeline was constructed. Nonetheless, if the Obama administration was committed to restricting greenhouse gas emissions, it is difficult to see why it would support the building of a pipeline that would facilitate bringing some of the world’s dirtiest oil to market.

In the same vein, Sernovitz is right that it is difficult to see how anything about the growth of the housing bubble and its subsequent collapse would have been very different if Glass-Steagall were still in place. And, it is possible in principle to regulate bank’s risky practices without Glass-Steagall, as the Volcker rule is doing. However, enforcement tends to weaken over time under industry pressure, which is a reason why the clear lines of Glass-Steagall can be beneficial. Furthermore, as with Keystone, if we want to restrict banks’ power, what is the advantage of letting them get bigger and more complex?

The repeal of Glass-Steagall was sold in large part by boasting of the potential synergies from combining investment and commercial banking under one roof. But if the operations are kept completely separate, as is supposed to be the case, where are the synergies?

But the strangest part of Sernovitz’s story is that he leaves out Sanders’ financial transactions tax (FTT) altogether. This is bizarre, because the FTT is essentially a hatchet blow to the waste and exorbitant salaries in the industry.

Most research shows that trading volume is very responsive to the cost of trading, with most estimates putting the elasticity close to one. This means that if trading costs rise by 50 percent, then trading volume declines by 50 percent. (In its recent analysis of FTTs, the Tax Policy Center assumed that the elasticity was 1.5, meaning that trading volume decline by 150 percent of the increase in trading costs.) The implication of this finding is that the financial industry would pay the full cost of a financial transactions tax in the form of reduced trading revenue.

The Tax Policy Center estimated that a 0.1 percent tax on stock trades, scaled with lower taxes on other assets, would raise $50 billion a year in tax revenue. The implied reduction in trading revenue was even larger. Senator Sanders has proposed a tax of 0.5 percent on equities (also with a scaled tax on other assets). This would lead to an even larger reduction in revenue for the financial industry.

It is incredible that Sernovitz would ignore a policy with such enormous consequences for the financial sector in his assessment of which candidate would be tougher on Wall Street. Sanders FTT would almost certainly do more to change behavior on Wall Street than everything that Clinton has proposed taken together, by a rather large margin. Leaving out the FTT in this comparison is sort of like evaluating the New England Patriots’ Super Bowl prospects without discussing their quarterback.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an article on a commitment by Secretary of State John Kerry that the United States would double its aid to developing countries for dealing with climate change from $400 million annually to $800 million by 2020. Those who are worried about the tax increases needed to pay for this aid may be interested in learning that the additional commitment comes to a bit less than 0.009 percent of the $4.7 trillion the government is projected to spend in 2020.

The Washington Post had an article on a commitment by Secretary of State John Kerry that the United States would double its aid to developing countries for dealing with climate change from $400 million annually to $800 million by 2020. Those who are worried about the tax increases needed to pay for this aid may be interested in learning that the additional commitment comes to a bit less than 0.009 percent of the $4.7 trillion the government is projected to spend in 2020.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión