Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eduardo Porter had a good piece in the NYT pointing out the importance of having independent evaluations of government programs. The point is that the agencies undertaking a program have a strong incentive to exaggerate its benefits. He discusses this in the context of weatherization programs, but the problem applies more generally.

One of the areas noted by Porter is in the rating of mortgage backed securities (MBS). During the housing bubble years, the bond-rating agencies routinely gave investment grade ratings to MBS that were stuffed with junk mortgages. They ignored the quality of the mortgages because they wanted the businesss. They knew if they gave honest ratings, the investment banks would take away their business.

While Porter notes this is a problem with the issuer pays model (the banks pay the rating agencies), there actually is a very simple solution. In the debate on Dodd-Frank, Senator Al Franken proposed an amendment which would have the Securities and Exchange Commission pick the rating agency, instead of the issuer. The bank would still pay the fee, but since they were no longer controlling who got the work, it eliminated the conflict of interest problem. The amendment passed the senate 65-34, with considerable bi-partisan support.

Unfortunately, as Geithner indicated in his autobiography, the Obama administration apparently did not like the dismantling of the perfect system we have today. The Franken amendment was removed in the conference committee and the existing structure was left in place. This was possible because the bond-rating agencies and the banks have real lobbies, whereas the folks who like honest evaluations don’t. Of course the news media didn’t help much, giving the issue very little coverage. And what attention it did get largely reflected the views of the financial industry.

Anyhow, this is a good example of the difficulties in putting in place the sort of independent auditing process that Porter seeks.

Eduardo Porter had a good piece in the NYT pointing out the importance of having independent evaluations of government programs. The point is that the agencies undertaking a program have a strong incentive to exaggerate its benefits. He discusses this in the context of weatherization programs, but the problem applies more generally.

One of the areas noted by Porter is in the rating of mortgage backed securities (MBS). During the housing bubble years, the bond-rating agencies routinely gave investment grade ratings to MBS that were stuffed with junk mortgages. They ignored the quality of the mortgages because they wanted the businesss. They knew if they gave honest ratings, the investment banks would take away their business.

While Porter notes this is a problem with the issuer pays model (the banks pay the rating agencies), there actually is a very simple solution. In the debate on Dodd-Frank, Senator Al Franken proposed an amendment which would have the Securities and Exchange Commission pick the rating agency, instead of the issuer. The bank would still pay the fee, but since they were no longer controlling who got the work, it eliminated the conflict of interest problem. The amendment passed the senate 65-34, with considerable bi-partisan support.

Unfortunately, as Geithner indicated in his autobiography, the Obama administration apparently did not like the dismantling of the perfect system we have today. The Franken amendment was removed in the conference committee and the existing structure was left in place. This was possible because the bond-rating agencies and the banks have real lobbies, whereas the folks who like honest evaluations don’t. Of course the news media didn’t help much, giving the issue very little coverage. And what attention it did get largely reflected the views of the financial industry.

Anyhow, this is a good example of the difficulties in putting in place the sort of independent auditing process that Porter seeks.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post deserves credit for being the first major media outlet to discover the sharp increase in women’s labor force participation in Japan. It ran a piece headlined, “How American women fell behind Japanese women in the workplace,” which pointed out that employment rates are now higher for women in Japan than for the United States. (The difference in employment rates would be even larger if the article focused on prime-age — 25–54 — women.)

This shift has been clear in the OECD data for several years, but has been almost completely ignored. (There have been a few rants on the topic at BTP, for example here, here, and here.) Anyhow, it is always good to see the media discovering major trends in the world, even if they might be a bit slow to notice.

The Washington Post deserves credit for being the first major media outlet to discover the sharp increase in women’s labor force participation in Japan. It ran a piece headlined, “How American women fell behind Japanese women in the workplace,” which pointed out that employment rates are now higher for women in Japan than for the United States. (The difference in employment rates would be even larger if the article focused on prime-age — 25–54 — women.)

This shift has been clear in the OECD data for several years, but has been almost completely ignored. (There have been a few rants on the topic at BTP, for example here, here, and here.) Anyhow, it is always good to see the media discovering major trends in the world, even if they might be a bit slow to notice.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Why does the NYT find it so hard to separate its news reporting from opinion when it comes to trade deals? Yet again, we are told that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) can be “legacy making” for President Obama. After all it is:

“drawing together countries representing two-fifths of the global economy, from Canada and Chile to Japan and Australia, into a web of common rules governing trans-Pacific commerce. It is the capstone both of his economic agenda to expand exports and of his foreign policy ‘rebalance’ toward closer relations with fast-growing eastern Asia, after years of American preoccupation with the Middle East and North Africa.”

Sounds really exciting right? Well the vast majority of the “two-fifths of the global economy” is accounted for by the United States, Mexico, Canada, and Australia, countries that were already drawn together in trade deals. For these countries the TPP will have little impact on trade. The only countries in the deal that really qualify as “fast-growing eastern Asia” would be Malaysia and Vietnam.

As a practical matter, the stronger patent and copyright protections in the pact may do more to impede trade than the tariff reductions do to promote trade, making its status as a “free-trade” agreement questionable. (To its credit, the NYT piece did not use this term.) It would be useful if the paper focused more on the facts and less on the celebration.

Why does the NYT find it so hard to separate its news reporting from opinion when it comes to trade deals? Yet again, we are told that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) can be “legacy making” for President Obama. After all it is:

“drawing together countries representing two-fifths of the global economy, from Canada and Chile to Japan and Australia, into a web of common rules governing trans-Pacific commerce. It is the capstone both of his economic agenda to expand exports and of his foreign policy ‘rebalance’ toward closer relations with fast-growing eastern Asia, after years of American preoccupation with the Middle East and North Africa.”

Sounds really exciting right? Well the vast majority of the “two-fifths of the global economy” is accounted for by the United States, Mexico, Canada, and Australia, countries that were already drawn together in trade deals. For these countries the TPP will have little impact on trade. The only countries in the deal that really qualify as “fast-growing eastern Asia” would be Malaysia and Vietnam.

As a practical matter, the stronger patent and copyright protections in the pact may do more to impede trade than the tariff reductions do to promote trade, making its status as a “free-trade” agreement questionable. (To its credit, the NYT piece did not use this term.) It would be useful if the paper focused more on the facts and less on the celebration.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Naturally, the paper had an editorial celebrating a deal on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In it they referred to the TPP as a free-trade deal and denounced opponents for appealing to “protectionist sentiment.” If we want to think about this one seriously, does the Post have any evidence whatsoever that the reduction in tariffs and other barriers in the TPP are economically larger than the increase in protectionist measures in the form of copyrights and patents? If so, it has never bothered to share this information with readers.

We get that the Washington Post likes patent and copyright protection. Its friends and advertisers benefit from these government granted monopolies. But, just because the Post likes patents and copyrights does not make them any less protectionist.

At a time like this it is hard not to remember when the Post claimed that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 because of NAFTA. (I have no idea why they chose 1987 as the base year.) The actual growth figure was 83 percent. Anyhow, the point is that these are not people who feel bound by the evidence in making their case for trade agreements.

Naturally, the paper had an editorial celebrating a deal on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In it they referred to the TPP as a free-trade deal and denounced opponents for appealing to “protectionist sentiment.” If we want to think about this one seriously, does the Post have any evidence whatsoever that the reduction in tariffs and other barriers in the TPP are economically larger than the increase in protectionist measures in the form of copyrights and patents? If so, it has never bothered to share this information with readers.

We get that the Washington Post likes patent and copyright protection. Its friends and advertisers benefit from these government granted monopolies. But, just because the Post likes patents and copyrights does not make them any less protectionist.

At a time like this it is hard not to remember when the Post claimed that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 because of NAFTA. (I have no idea why they chose 1987 as the base year.) The actual growth figure was 83 percent. Anyhow, the point is that these are not people who feel bound by the evidence in making their case for trade agreements.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

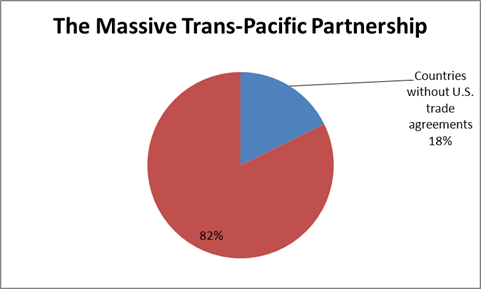

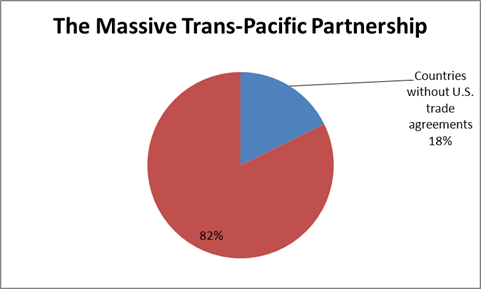

It is amazing how the elite media can be dragged along by their noses into accepting that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) can have a big impact on trade and growth. If I had a dollar for every time the deal was described as “massive” or that we were told what share of world trade will be covered by the TPP, I would be richer than Bill Gates. The reality is that the vast majority of the trade between the countries in the TPP is already covered by trade agreements as can be seen.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

We continue to hear superlatives even as the evidence suggests the trade impact will be trivial. For example, the NYT reported that U.S. tariffs on Japanese cars will be phased out over 30 years. Wow! The most optimistic growth estimates show a gain by 2027 of less than 0.4 percent, roughly two months of normal GDP growth.

This doesn’t mean that the TPP can’t have an impact. It will lock in a regulatory structure, the exact parameters of which are yet to be seen. We do know that the folks at the table came from places like General Electric and Monsanto, not the AFL-CIO and the Sierra Club. We also know that it will mean paying more for drugs and other patent and copyright protected material (forms of protection, whose negative impact is never included in growth projections), but we don’t yet know how much.

We also know that the Obama administration gave up an opportunity to include currency rules. This means that the trade deficit is likely to persist long into the future. This deficit has been a persistent source of gap in demand, leading to millions of lost jobs. We filled this demand in the 1990s with the stock bubble and in the last decade with the housing bubble. It seems the latest plan from the Fed is that we simply won’t fill the gap in this decade.

It is amazing how the elite media can be dragged along by their noses into accepting that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) can have a big impact on trade and growth. If I had a dollar for every time the deal was described as “massive” or that we were told what share of world trade will be covered by the TPP, I would be richer than Bill Gates. The reality is that the vast majority of the trade between the countries in the TPP is already covered by trade agreements as can be seen.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

We continue to hear superlatives even as the evidence suggests the trade impact will be trivial. For example, the NYT reported that U.S. tariffs on Japanese cars will be phased out over 30 years. Wow! The most optimistic growth estimates show a gain by 2027 of less than 0.4 percent, roughly two months of normal GDP growth.

This doesn’t mean that the TPP can’t have an impact. It will lock in a regulatory structure, the exact parameters of which are yet to be seen. We do know that the folks at the table came from places like General Electric and Monsanto, not the AFL-CIO and the Sierra Club. We also know that it will mean paying more for drugs and other patent and copyright protected material (forms of protection, whose negative impact is never included in growth projections), but we don’t yet know how much.

We also know that the Obama administration gave up an opportunity to include currency rules. This means that the trade deficit is likely to persist long into the future. This deficit has been a persistent source of gap in demand, leading to millions of lost jobs. We filled this demand in the 1990s with the stock bubble and in the last decade with the housing bubble. It seems the latest plan from the Fed is that we simply won’t fill the gap in this decade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Remember when then Federal Reserve Board Chair Ben Bernanke assured the public that the problems in the financial system will be restricted to the subprime market? This one ranks, along with some comments from and about Alan Greenspan, as one of the worst economic predictions of all time. In other words, the folks at the Fed really missed it.

This is worth remembering because it seems that the Fed is trying to get the excuse making going in advance for the next economic crisis. The NYT reported on a Fed conference where they expressed skepticism as to whether they could stop the next crisis.

There are a range of views presented, not all of them silly. (Using interest rates as the primary tool against bubbles is not a good strategy.) However the idea that the Fed is helpless against bubbles looks like some serious lowering of expectations.

The distortions created by the housing bubble were easy to see by anyone with open eyes. Residential construction as a share of GDP was hitting record levels even as demographics would have suggested the opposite. (Baby boomers were retiring or at least downsizing.) Consumption was hitting record highs as a share of disposable income, driven by housing bubble wealth. House prices had surged by 70 percent above inflation, after tracking the overall inflation rate for the prior century. And the bad loans were there en masse for anyone who cared to notice.

The Fed has a variety of tools but the most simple one is simply talking about a bubble. The financial markets will not ignore information (not a mumbled “irrational exuberance”) from the Fed as they showed in response to Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s comments about bubbles in the social media and biotech sectors.

There is no reason that the Fed should not have been issuing clear warnings (i.e. massive quantities of research) documenting the bubble from 2002 onward. The only cost to the Fed is a few researchers time, the potential savings are in the trillions. That seems a no-brainer. The Fed should have also been using its regulatory power to curb the issuance and sale of bad mortgages, but information is a good place to start.

Also, it is not plausible for an organization that argues an inflation target is important to say that information from the Fed has no impact on markets. It obviously believes otherwise.

Remember when then Federal Reserve Board Chair Ben Bernanke assured the public that the problems in the financial system will be restricted to the subprime market? This one ranks, along with some comments from and about Alan Greenspan, as one of the worst economic predictions of all time. In other words, the folks at the Fed really missed it.

This is worth remembering because it seems that the Fed is trying to get the excuse making going in advance for the next economic crisis. The NYT reported on a Fed conference where they expressed skepticism as to whether they could stop the next crisis.

There are a range of views presented, not all of them silly. (Using interest rates as the primary tool against bubbles is not a good strategy.) However the idea that the Fed is helpless against bubbles looks like some serious lowering of expectations.

The distortions created by the housing bubble were easy to see by anyone with open eyes. Residential construction as a share of GDP was hitting record levels even as demographics would have suggested the opposite. (Baby boomers were retiring or at least downsizing.) Consumption was hitting record highs as a share of disposable income, driven by housing bubble wealth. House prices had surged by 70 percent above inflation, after tracking the overall inflation rate for the prior century. And the bad loans were there en masse for anyone who cared to notice.

The Fed has a variety of tools but the most simple one is simply talking about a bubble. The financial markets will not ignore information (not a mumbled “irrational exuberance”) from the Fed as they showed in response to Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s comments about bubbles in the social media and biotech sectors.

There is no reason that the Fed should not have been issuing clear warnings (i.e. massive quantities of research) documenting the bubble from 2002 onward. The only cost to the Fed is a few researchers time, the potential savings are in the trillions. That seems a no-brainer. The Fed should have also been using its regulatory power to curb the issuance and sale of bad mortgages, but information is a good place to start.

Also, it is not plausible for an organization that argues an inflation target is important to say that information from the Fed has no impact on markets. It obviously believes otherwise.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Washington Post article on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) referred to President Obama’s assertion that the pact will boost growth. It would have been appropriate to point out that almost no economists support the claim that the pact will have a noticeable positive impact on growth.

The most favorable positive assessment comes from the Peterson Institute. It projects that the agreement would boost growth by 0.03 percentage points annually over the next dozen years. This would mean, for example, that if growth would have been 2.2 percent without the TPP, it would be 2.23 percent with the TPP. Other projections have been lower. For example, an analysis by the United States Department of Agriculture concluded that the gains would be too small to measure.

It is also worth noting that none of these studies took into account the negative impact on growth from the higher drug prices that would be the result of the stronger protectionist measures in the TPP. The United States currently spends more than $400 billion a year on prescription drugs. This amount will almost certainly increase in both the U.S. and elsewhere as a result of stronger patent and related protections in the TPP. Higher drug prices will pull money out of people’s pockets, leaving less to spend in other areas, thereby slowing growth.

For these reasons, it would have been useful to point out that President Obama is making a Trump-like claim in arguing that the TPP is a mechanism to increase economic growth. That is simply not a plausible story.

A Washington Post article on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) referred to President Obama’s assertion that the pact will boost growth. It would have been appropriate to point out that almost no economists support the claim that the pact will have a noticeable positive impact on growth.

The most favorable positive assessment comes from the Peterson Institute. It projects that the agreement would boost growth by 0.03 percentage points annually over the next dozen years. This would mean, for example, that if growth would have been 2.2 percent without the TPP, it would be 2.23 percent with the TPP. Other projections have been lower. For example, an analysis by the United States Department of Agriculture concluded that the gains would be too small to measure.

It is also worth noting that none of these studies took into account the negative impact on growth from the higher drug prices that would be the result of the stronger protectionist measures in the TPP. The United States currently spends more than $400 billion a year on prescription drugs. This amount will almost certainly increase in both the U.S. and elsewhere as a result of stronger patent and related protections in the TPP. Higher drug prices will pull money out of people’s pockets, leaving less to spend in other areas, thereby slowing growth.

For these reasons, it would have been useful to point out that President Obama is making a Trump-like claim in arguing that the TPP is a mechanism to increase economic growth. That is simply not a plausible story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión