Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen gave a speech yesterday in which she referred to the value of the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target and warned of the uncertainty caused by any effort to raise the target to a higher rate. While having more stable prices is undoubtedly better than having less stable prices, it is a bit bizarre how this 2.0 percent has become the object of worship.

First, to those who care about such things it should be disconcerting that the inflation rate has been consistently below 2.0 percent for the last six years. That might suggest the 2.0 percent target is not all that meaningful. People who expected 2.0 percent inflation would have been shown wrong.

But what seems more striking is that while domestic inflation might be relatively stable, the rate of change of import prices is far from stable. The chart below shows the rate of change of non-oil import prices over the last three decades.

Change in Non-Oil Import Prices (prior 12 months)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen the inflation rate for non-oil import prices fluctuate widely, for example going from -4.2 percent in the period from March 2001 to March 2002 to positive 2.4 percent in the following twelve months. (The fluctations would be larger if we included oil.) Since imports are more than 15 percent of the economy, how can these sorts of fluctuations not pose a problem, but a gradual increase from 2.0 percent to 4.0 percent inflation be a big deal? If there is some logic to the commonly held view that Yellen is espousing, it is hard to see.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen gave a speech yesterday in which she referred to the value of the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target and warned of the uncertainty caused by any effort to raise the target to a higher rate. While having more stable prices is undoubtedly better than having less stable prices, it is a bit bizarre how this 2.0 percent has become the object of worship.

First, to those who care about such things it should be disconcerting that the inflation rate has been consistently below 2.0 percent for the last six years. That might suggest the 2.0 percent target is not all that meaningful. People who expected 2.0 percent inflation would have been shown wrong.

But what seems more striking is that while domestic inflation might be relatively stable, the rate of change of import prices is far from stable. The chart below shows the rate of change of non-oil import prices over the last three decades.

Change in Non-Oil Import Prices (prior 12 months)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen the inflation rate for non-oil import prices fluctuate widely, for example going from -4.2 percent in the period from March 2001 to March 2002 to positive 2.4 percent in the following twelve months. (The fluctations would be larger if we included oil.) Since imports are more than 15 percent of the economy, how can these sorts of fluctuations not pose a problem, but a gradual increase from 2.0 percent to 4.0 percent inflation be a big deal? If there is some logic to the commonly held view that Yellen is espousing, it is hard to see.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

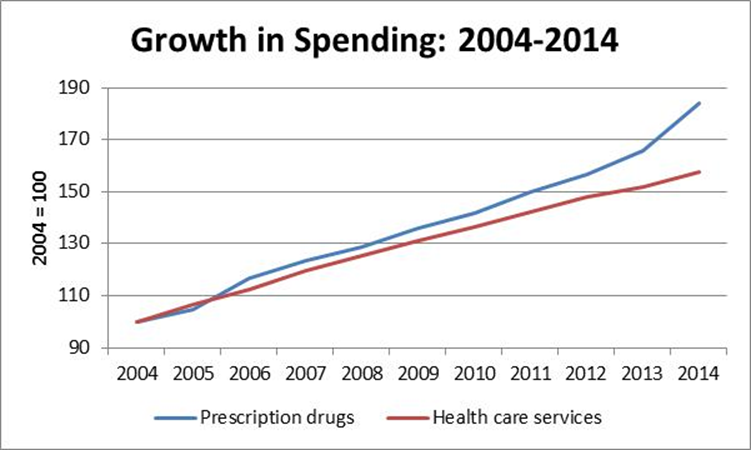

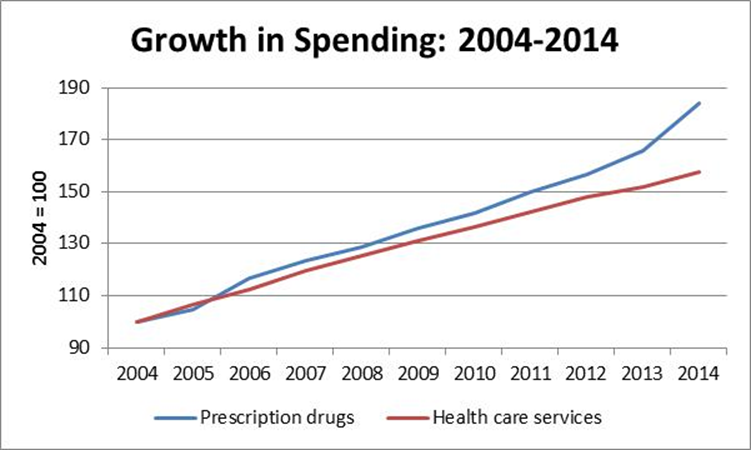

Your choices are a professor holding a chair endowed by a pharmaceutical testing company and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The professor, Darius Lakdawalla, holds the Quintiles chair at the School of Pharmacy at the University of Southern California. In an NYT “Room for Debate” piece on pharmaceutical prices (I was also a contributor), Lakdawalla told readers:

“[D]rug spending has been growing no faster than overall health care spending over the past 10 years.”

That is not what the good people at BEA say. According to the National Income and Product Accounts (Table 2.4.5U) prescription drug spending increased at average annual rate of 6.3 percent over the years from 2004 to 2014, rising from $203.6 billion in 2004 to $374.7 billion in 2014 (Line 122). By contrast, spending on health care services rose at annual rate of 4.7 percent over this period, going from $1240.1 billion in 2004 to $1954.0 billion in 2014 (Line 168). This is shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The BEA data seem to be showing a very different story that what Professor Lakdawalla is telling us. In fact, over the last five years the gap in growth rates is even larger, with prescription drug spending rising at a 6.2 percent annual rate and spending on health care services rising at just a 3.7 percent annual rate. That difference could explain why presidential candidates apparently feel the need to talk about the cost of prescription drugs.

Your choices are a professor holding a chair endowed by a pharmaceutical testing company and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The professor, Darius Lakdawalla, holds the Quintiles chair at the School of Pharmacy at the University of Southern California. In an NYT “Room for Debate” piece on pharmaceutical prices (I was also a contributor), Lakdawalla told readers:

“[D]rug spending has been growing no faster than overall health care spending over the past 10 years.”

That is not what the good people at BEA say. According to the National Income and Product Accounts (Table 2.4.5U) prescription drug spending increased at average annual rate of 6.3 percent over the years from 2004 to 2014, rising from $203.6 billion in 2004 to $374.7 billion in 2014 (Line 122). By contrast, spending on health care services rose at annual rate of 4.7 percent over this period, going from $1240.1 billion in 2004 to $1954.0 billion in 2014 (Line 168). This is shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The BEA data seem to be showing a very different story that what Professor Lakdawalla is telling us. In fact, over the last five years the gap in growth rates is even larger, with prescription drug spending rising at a 6.2 percent annual rate and spending on health care services rising at just a 3.7 percent annual rate. That difference could explain why presidential candidates apparently feel the need to talk about the cost of prescription drugs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There is an annoying tendency among elite types to assume that their ignorance on important issues is shared by others. Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson gave us a great example of the effort to project his misunderstanding of the economy when he told readers:

“Over the past decade, there has been a profound shift in its public standing. Before the 2008–09 financial crisis, the Fed enjoyed enormous prestige and freedom of action. All the Fed had to do, it seemed, was tweak short-term interest rates to keep expansions long and recessions short. What’s clear now is that we vastly exaggerated the Fed’s powers of economic management.”

Sorry folks, but Samuelson is describing his own need for rethinking, not the need for those with a better understanding of the economy. We had recalled the weak recovery from the 2001 recession. While the GDP recovery was impressive, the labor market recovery was not. While the recession officially ended in December of 2001, we continued to lose jobs all through 2002 and until September of 2003. We didn’t get back the jobs lost in the downturn until January of 2005. At the time this was the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression. The Fed’s pushing its short-term interest rate down to just 1.0 percent did not seem to help much.

This led us to be very concerned about the difficulty in recovering from the recession that would inevitably follow the collapse of the housing bubble, which was visible to those with clear eyes long before it burst. So the confusion on these issues belongs to Samuelson, not to “we.”

Unfortunately his confusion continues. He tells readers that the economy is near full employment. This is only true if we think that millions of people in their thirties and forties have opted for early retirement since the beginning of the recession. These people have dropped out of the labor force and are therefore not counted as unemployed. The amount of involuntary part-time and quit rates are still both at recession levels.

He then says:

“the financial crisis and Great Recession so traumatized consumers and businesses that they reined in their spending and risk-taking.”

Nope, consumption is actually very high relative to disposable income or GDP. This is a fact that is well know to those with access to government GDP data (i.e. everyone). Similarly, the investment share of GDP is pretty much back to its pre-recession level.

The explanation for the continued doldrums is actually very simple. We have nothing to fill the demand gap created by a trade deficit of 3 percent of GDP (@ $500 billion a year). In the last decade we had the housing bubble, but in the absence of the bubble, there is no easy way to fill that gap. We could do it with budget deficits, but that gets our friends at the Post really upset. Instead, we get high unemployment and weak wage growth, and people are unhappy. It’s all so complicated.

There is an annoying tendency among elite types to assume that their ignorance on important issues is shared by others. Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson gave us a great example of the effort to project his misunderstanding of the economy when he told readers:

“Over the past decade, there has been a profound shift in its public standing. Before the 2008–09 financial crisis, the Fed enjoyed enormous prestige and freedom of action. All the Fed had to do, it seemed, was tweak short-term interest rates to keep expansions long and recessions short. What’s clear now is that we vastly exaggerated the Fed’s powers of economic management.”

Sorry folks, but Samuelson is describing his own need for rethinking, not the need for those with a better understanding of the economy. We had recalled the weak recovery from the 2001 recession. While the GDP recovery was impressive, the labor market recovery was not. While the recession officially ended in December of 2001, we continued to lose jobs all through 2002 and until September of 2003. We didn’t get back the jobs lost in the downturn until January of 2005. At the time this was the longest period without job growth since the Great Depression. The Fed’s pushing its short-term interest rate down to just 1.0 percent did not seem to help much.

This led us to be very concerned about the difficulty in recovering from the recession that would inevitably follow the collapse of the housing bubble, which was visible to those with clear eyes long before it burst. So the confusion on these issues belongs to Samuelson, not to “we.”

Unfortunately his confusion continues. He tells readers that the economy is near full employment. This is only true if we think that millions of people in their thirties and forties have opted for early retirement since the beginning of the recession. These people have dropped out of the labor force and are therefore not counted as unemployed. The amount of involuntary part-time and quit rates are still both at recession levels.

He then says:

“the financial crisis and Great Recession so traumatized consumers and businesses that they reined in their spending and risk-taking.”

Nope, consumption is actually very high relative to disposable income or GDP. This is a fact that is well know to those with access to government GDP data (i.e. everyone). Similarly, the investment share of GDP is pretty much back to its pre-recession level.

The explanation for the continued doldrums is actually very simple. We have nothing to fill the demand gap created by a trade deficit of 3 percent of GDP (@ $500 billion a year). In the last decade we had the housing bubble, but in the absence of the bubble, there is no easy way to fill that gap. We could do it with budget deficits, but that gets our friends at the Post really upset. Instead, we get high unemployment and weak wage growth, and people are unhappy. It’s all so complicated.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I see my friends Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong are arguing over whether the pressure from the banking industry for the Fed to raise interest rates is the result of their calculation that higher interest rates would raise their profits or is it just ignorance of the way the economy works. Krugman argues the former and DeLong the latter. I would mostly agree with Krugman, but for a slightly different reason.

I don’t see the clear link, claimed by Krugman, between higher Fed interest rates and higher net lending margins for banks (the difference between the interest rate they charge on loans and the interest rate they pay on deposits). Such a link may exist, but his data don’t show it. On the other hand, I think it is still not hard to make a case for banks’ self-interest in following a tight money policy.

An unexpected rise in the inflation rate is clearly harmful to banks’ bottom line. This will lead to a rise in long-term interest rates and loss in the value of their outstanding debt. This is very bad news for them.

While we (the three of us) can agree that such a jump in inflation is highly unlikely in the current economic situation, it is not zero. Furthermore, a stronger economy increases this risk. If we assume that the banks care little about lower unemployment (they may not be bothered by lower unemployment, but high unemployment is not something they wake up every morning worrying about), then they are faced with a trade-off between a greater risk of something they really fear and something to which they are largely indifferent. It shouldn’t be surprising that they want to the Fed to act to ensure the event they really fear (higher inflation) does not happen. Hence the push to raise interest rates.

I suspect also there is a strong desire to head off any idea that the government can shape the economy in important ways. There is enormous value for the rich to believe that they got where they are through their talent and hard work and that those facing difficult economic times lack these qualities. It makes for a much more troubling world view to suggest that tens of millions of people might be struggling because of bad fiscal policy from the government and inept monetary policy by the Fed.

I see my friends Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong are arguing over whether the pressure from the banking industry for the Fed to raise interest rates is the result of their calculation that higher interest rates would raise their profits or is it just ignorance of the way the economy works. Krugman argues the former and DeLong the latter. I would mostly agree with Krugman, but for a slightly different reason.

I don’t see the clear link, claimed by Krugman, between higher Fed interest rates and higher net lending margins for banks (the difference between the interest rate they charge on loans and the interest rate they pay on deposits). Such a link may exist, but his data don’t show it. On the other hand, I think it is still not hard to make a case for banks’ self-interest in following a tight money policy.

An unexpected rise in the inflation rate is clearly harmful to banks’ bottom line. This will lead to a rise in long-term interest rates and loss in the value of their outstanding debt. This is very bad news for them.

While we (the three of us) can agree that such a jump in inflation is highly unlikely in the current economic situation, it is not zero. Furthermore, a stronger economy increases this risk. If we assume that the banks care little about lower unemployment (they may not be bothered by lower unemployment, but high unemployment is not something they wake up every morning worrying about), then they are faced with a trade-off between a greater risk of something they really fear and something to which they are largely indifferent. It shouldn’t be surprising that they want to the Fed to act to ensure the event they really fear (higher inflation) does not happen. Hence the push to raise interest rates.

I suspect also there is a strong desire to head off any idea that the government can shape the economy in important ways. There is enormous value for the rich to believe that they got where they are through their talent and hard work and that those facing difficult economic times lack these qualities. It makes for a much more troubling world view to suggest that tens of millions of people might be struggling because of bad fiscal policy from the government and inept monetary policy by the Fed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what folks must have been speculating about when they read Neil Irwin’s account of the Fed’s decision to put off a hike in interest rates this week. Near the end of the piece Irwin tells readers:

“As Stanley Fischer, the Fed vice chairman, said in a television interview last month, if the Fed waits until it is absolutely certain it is time to raise rates, it will probably be too late.

“In other words, Fed officials inevitably have to make a decision based on what their models predict, not on cold hard evidence.”

Huh? What exactly is the bad thing that happens if it’s “too late” when the Fed acts? In the models I know, we start to see some acceleration of inflation. Given that the inflation rate has been well below the Fed’s target for most of the last six years, the Fed should want the inflation rate to accelerate, at least if it is following its stated policy of targeting a 2.0 percent average rate of inflation. (This rate is too low, according to folks like I.M.F. chief economist Olivier Blanchard.) The inflation rate could average 3.0 percent over the next four years and still be consistent with the Fed’s stated target.

None of the standard models shows a rapid acceleration of inflation as a result of the Fed being “too late.” They show the inflation rate increasing very gradually. According to the most recent projections from the Congressional Budget Office being a full percentage point below full employment for a full year would lead to just a 0.3 percentage point rise in the rate of inflation. This would appear to be the cost of being too late in the standard models.

Perhaps Irwin could tell readers what Mr. Fischer was thinking about in giving his warning.

Addendum:

The headline writer for this piece deserves some grief for writing that “Yellen blinked” in reference to her decision not to support an interest rate hike. The implication is that this decision was due to a lack of will as opposed to good judgement. This is not the job of the headline writer to determine, nor the implication of the piece. Thanks Jeff for pointing this out.

That’s what folks must have been speculating about when they read Neil Irwin’s account of the Fed’s decision to put off a hike in interest rates this week. Near the end of the piece Irwin tells readers:

“As Stanley Fischer, the Fed vice chairman, said in a television interview last month, if the Fed waits until it is absolutely certain it is time to raise rates, it will probably be too late.

“In other words, Fed officials inevitably have to make a decision based on what their models predict, not on cold hard evidence.”

Huh? What exactly is the bad thing that happens if it’s “too late” when the Fed acts? In the models I know, we start to see some acceleration of inflation. Given that the inflation rate has been well below the Fed’s target for most of the last six years, the Fed should want the inflation rate to accelerate, at least if it is following its stated policy of targeting a 2.0 percent average rate of inflation. (This rate is too low, according to folks like I.M.F. chief economist Olivier Blanchard.) The inflation rate could average 3.0 percent over the next four years and still be consistent with the Fed’s stated target.

None of the standard models shows a rapid acceleration of inflation as a result of the Fed being “too late.” They show the inflation rate increasing very gradually. According to the most recent projections from the Congressional Budget Office being a full percentage point below full employment for a full year would lead to just a 0.3 percentage point rise in the rate of inflation. This would appear to be the cost of being too late in the standard models.

Perhaps Irwin could tell readers what Mr. Fischer was thinking about in giving his warning.

Addendum:

The headline writer for this piece deserves some grief for writing that “Yellen blinked” in reference to her decision not to support an interest rate hike. The implication is that this decision was due to a lack of will as opposed to good judgement. This is not the job of the headline writer to determine, nor the implication of the piece. Thanks Jeff for pointing this out.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is apparently disappointed that the Fed did not decide to raise interest rates and slow the pace of economic growth. Its editorial told readers:

“But there are risks [from not raising rates], too, such as the formation of asset bubbles and the sheer loss of credibility the Fed suffers every time it flirts with a new interest rate policy and then doesn’t deliver. The latter risk may have been compounded by the Fed’s so openly acknowledging that its decisions are subject to the vagaries of China’s economic “rebalancing,” and the non transparent policy processes in Beijing upon which that depends.”

The second part of this paragraph seems to suggest that the Post is unhappy that Yellen would take into account the impact of the world economy on the United States in her decisions on interest rates. That’s an interesting criticism.

But the first part is the fun part. The Post is worried about bubbles? This is a paper that hosted James K. Glassman, co-author of Dow 36,000, through the stock bubble years. In the housing bubble years its main commentator on the real estate market was David Lereah, the chief economist of the National Association of Realtor and the author of the 2005 classic, Why the Housing Boom Will not Bust and How You Can Profit from It.

It would be interesting if the Post’s editorial board had evidence of a bubble threatening the economy. If they do, they didn’t bother sharing it with their readers. It would be reasonable to expect such evidence before demanding that the Fed raise interest rates to keep workers from getting jobs and pay raises.

The Washington Post is apparently disappointed that the Fed did not decide to raise interest rates and slow the pace of economic growth. Its editorial told readers:

“But there are risks [from not raising rates], too, such as the formation of asset bubbles and the sheer loss of credibility the Fed suffers every time it flirts with a new interest rate policy and then doesn’t deliver. The latter risk may have been compounded by the Fed’s so openly acknowledging that its decisions are subject to the vagaries of China’s economic “rebalancing,” and the non transparent policy processes in Beijing upon which that depends.”

The second part of this paragraph seems to suggest that the Post is unhappy that Yellen would take into account the impact of the world economy on the United States in her decisions on interest rates. That’s an interesting criticism.

But the first part is the fun part. The Post is worried about bubbles? This is a paper that hosted James K. Glassman, co-author of Dow 36,000, through the stock bubble years. In the housing bubble years its main commentator on the real estate market was David Lereah, the chief economist of the National Association of Realtor and the author of the 2005 classic, Why the Housing Boom Will not Bust and How You Can Profit from It.

It would be interesting if the Post’s editorial board had evidence of a bubble threatening the economy. If they do, they didn’t bother sharing it with their readers. It would be reasonable to expect such evidence before demanding that the Fed raise interest rates to keep workers from getting jobs and pay raises.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Andrew Ross Sorkin has a good piece today pointing out that Jeb Bush’s tax plan calls for ending the deductibility for corporate interest payments. Under the current system the tax code effectively gives encouragement for companies to borrow, since the interest they pay is tax deductible.

Private equity companies take advantage of this provision, routinely having the companies they acquire borrow as much as possible, often to make payments to the private equity company. This leaves the acquired company vulnerable to any business downturn, which is why many acquired companies go bankrupt.

The interest deduction is a large part of private equity profits in many cases. Since some private equity partners are among the richest people in the country, ending this deduction would be enormously progressive. It would put an end to a practice that has allowed many private equity partners to make hundreds of millions or even billions by gaming the tax code.

Andrew Ross Sorkin has a good piece today pointing out that Jeb Bush’s tax plan calls for ending the deductibility for corporate interest payments. Under the current system the tax code effectively gives encouragement for companies to borrow, since the interest they pay is tax deductible.

Private equity companies take advantage of this provision, routinely having the companies they acquire borrow as much as possible, often to make payments to the private equity company. This leaves the acquired company vulnerable to any business downturn, which is why many acquired companies go bankrupt.

The interest deduction is a large part of private equity profits in many cases. Since some private equity partners are among the richest people in the country, ending this deduction would be enormously progressive. It would put an end to a practice that has allowed many private equity partners to make hundreds of millions or even billions by gaming the tax code.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión