In his review of former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s new book, Michael Kinsley tells us:

“Bernanke makes a compelling case that in 2007 and 2008, the world economy came very close to collapse, and only novel efforts by the Fed (cooperating with other United States and foreign government agencies) saved us from an economic catastrophe greater than the Great Depression.”

The Great Depression lasted for more than a decade because the government did not spend enough money to get the economy back to a normal level of output. It eventually did get the economy back to full employment due to the spending associated with World War II. If the government had undertaken similar spending in 1931, for example to build up the infrastructure and to expand the provision of education and health care, the depression would have ended a decade sooner.

Unless there is some reason the United States government could not have spent money in 2009 if the banks had collapsed in 2008, then we did not have to worry about a Second Great Depression. No one has yet indicated what that reason could be. Even Republicans have consistently supported stimulus during downturns. (George W. Bush signed the first stimulus package in February of 2008 when the unemployment rate was 4.7 percent.) So the story of being saved from the Second Great Depression is entirely a myth that can be used to justify the bailout of the Wall Street banks.

In his review of former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s new book, Michael Kinsley tells us:

“Bernanke makes a compelling case that in 2007 and 2008, the world economy came very close to collapse, and only novel efforts by the Fed (cooperating with other United States and foreign government agencies) saved us from an economic catastrophe greater than the Great Depression.”

The Great Depression lasted for more than a decade because the government did not spend enough money to get the economy back to a normal level of output. It eventually did get the economy back to full employment due to the spending associated with World War II. If the government had undertaken similar spending in 1931, for example to build up the infrastructure and to expand the provision of education and health care, the depression would have ended a decade sooner.

Unless there is some reason the United States government could not have spent money in 2009 if the banks had collapsed in 2008, then we did not have to worry about a Second Great Depression. No one has yet indicated what that reason could be. Even Republicans have consistently supported stimulus during downturns. (George W. Bush signed the first stimulus package in February of 2008 when the unemployment rate was 4.7 percent.) So the story of being saved from the Second Great Depression is entirely a myth that can be used to justify the bailout of the Wall Street banks.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Washington Post editorial arguing for the adoption of a budget proposal put forward by Representative Scott Rigell applauded the plan’s call for using the chained CPI for indexing all taxes and benefits, including Social Security. It described the chained CPI as “more accurate.”

The chained CPI will typically show a lower rate of inflation than the CPI currently used since it accounts for substitutions in consumption, as people change their consumption patterns in response to changes in prices. (It changes the weights in the index assigned to different price increases, it doesn’t count savings from switching from more expensive to less expensive items.)

While there is an argument for picking up the impact of substitution, it is important to note that this may not be valid for the senior population that relies on Social Security. It is possible that seniors are less likely to change their consumption patterns by switching items or outlets in response to price increases. We could determine whether or not this is the case by constructing a full price index for the elderly, which would track the prices of the specific goods and services they consume and look at the outlets where they buy them.

This is what Congress would do if it was interested in an accurate measure of the rate of price increase experienced by seniors. Switching to the chained CPI will mean lower benefits (@ 3 percent for the average senior over the course of their retirement), the Post has no clue as to whether it would be more accurate.

A Washington Post editorial arguing for the adoption of a budget proposal put forward by Representative Scott Rigell applauded the plan’s call for using the chained CPI for indexing all taxes and benefits, including Social Security. It described the chained CPI as “more accurate.”

The chained CPI will typically show a lower rate of inflation than the CPI currently used since it accounts for substitutions in consumption, as people change their consumption patterns in response to changes in prices. (It changes the weights in the index assigned to different price increases, it doesn’t count savings from switching from more expensive to less expensive items.)

While there is an argument for picking up the impact of substitution, it is important to note that this may not be valid for the senior population that relies on Social Security. It is possible that seniors are less likely to change their consumption patterns by switching items or outlets in response to price increases. We could determine whether or not this is the case by constructing a full price index for the elderly, which would track the prices of the specific goods and services they consume and look at the outlets where they buy them.

This is what Congress would do if it was interested in an accurate measure of the rate of price increase experienced by seniors. Switching to the chained CPI will mean lower benefits (@ 3 percent for the average senior over the course of their retirement), the Post has no clue as to whether it would be more accurate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I realize that this may come as a shock to the reporters and editors at the NYT, but companies are sometimes not truthful. That is why when G.E. announced that it was closing a factory in Wisconsin because it no longer had access to subsidized loans through the Export-Import Bank, the article should have said something to the effect of “G.E. claims to be closing factory because of lack of access to Export-Import Bank loans.” A serious newspaper would not take the assertion at face value and headline the article, “Ex-Im Bank Dispute Threatens G.E. Factory that Obama Praised.”

The New York Times has many outstanding reporters, but they don’t have any easy way of knowing if, for example, G.E. had plans to close this factory regardless of the fate of the Export-Import Bank. In that case, blaming the bank for the closure would be a convenient way to try to pressure Congress to renew funding.

If we try to guess the size of the subsidy that G.E. gets from the bank, if we assume that it might be $3 billion in loans or guarantees this year, with an average subsidy of 1.0 percentage point compared to the market interest rate, this comes to $30 million. By comparison, G.E. CEO Jeffrey Immelt received $37.2 million in compensation last year.

This would suggest that the subsidies that G.E. receives from the Ex-Im Bank are relatively small compared to the compensation of Mr. Immelt and other top executives. Cuts to their pay would be another possible route for keeping the Wisconsin plant operating.

Addendum:

It is worth noting that G.E.’s allegation is that the loss of a government subsidy is causing it to close a factory. It is not common for the NYT to highlight when a factory is closed due to the loss of a protective tariff. If the paper has a different attitude towards subsidies and tariffs it would be interesting to hear the basis for this position. Certainly it would not be justified in conventional economics.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks ltr and Robert Salzberg.

I realize that this may come as a shock to the reporters and editors at the NYT, but companies are sometimes not truthful. That is why when G.E. announced that it was closing a factory in Wisconsin because it no longer had access to subsidized loans through the Export-Import Bank, the article should have said something to the effect of “G.E. claims to be closing factory because of lack of access to Export-Import Bank loans.” A serious newspaper would not take the assertion at face value and headline the article, “Ex-Im Bank Dispute Threatens G.E. Factory that Obama Praised.”

The New York Times has many outstanding reporters, but they don’t have any easy way of knowing if, for example, G.E. had plans to close this factory regardless of the fate of the Export-Import Bank. In that case, blaming the bank for the closure would be a convenient way to try to pressure Congress to renew funding.

If we try to guess the size of the subsidy that G.E. gets from the bank, if we assume that it might be $3 billion in loans or guarantees this year, with an average subsidy of 1.0 percentage point compared to the market interest rate, this comes to $30 million. By comparison, G.E. CEO Jeffrey Immelt received $37.2 million in compensation last year.

This would suggest that the subsidies that G.E. receives from the Ex-Im Bank are relatively small compared to the compensation of Mr. Immelt and other top executives. Cuts to their pay would be another possible route for keeping the Wisconsin plant operating.

Addendum:

It is worth noting that G.E.’s allegation is that the loss of a government subsidy is causing it to close a factory. It is not common for the NYT to highlight when a factory is closed due to the loss of a protective tariff. If the paper has a different attitude towards subsidies and tariffs it would be interesting to hear the basis for this position. Certainly it would not be justified in conventional economics.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks ltr and Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a NYT review of Roger Lowenstein’s book on the Federal Reserve Board, Robert Rubin touts the virtues of the Fed’s independence from political control. He decries efforts to make the Fed more accountable to Congress.

While the Fed may not feel as though it must directly respond to Congress, that does not mean it is not responsive to political pressures. In the last thirty five years, it has maintained policies that have on average kept the unemployment rate almost a full percentage point above the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (0.5 percentage points excluding the Great Recession). By contrast, in the prior three decades the unemployment rate had averaged half a percentage point less than CBO’s estimate of the NAIRU.

Source: Baker and Bernstein, 2013.

The higher unemployment acts as an insurance policy against inflation. The higher unemployment kept millions of people from working and deprived tens of millions of workers of the bargaining power needed to secure real wage increases. While modestly higher inflation would be a matter of little concern to most workers (especially since it is being driven in part by higher wages), it would be very upsetting to the financial sector since the value of the debt they own would be reduced.

The financial industry has a grossly disproportionate influence on the Fed due to its design. They largely control the 12 district banks. In addition, the governors appointed by the president tend to be more responsive to the concerns of the financial industry than other sectors of the economy. It is certainly possible that if the Fed were not so tied to the financial industry, it would have paid more attention to the housing bubble as it was growing. The industry made huge amounts of money from the mortgages that fueled the bubble. (In this context, it is probably worth noting that Mr. Rubin made more than $100 million from his position as a top executive at Citigroup during the bubble years.)

For these reasons, the public may not be as happy about the Fed’s lack of accountability to democratically elected bodies as Mr. Rubin. Many might prefer a central bank that is concerned more about workers than bankers.

Addendum:

On this topic, it is probably worth noting that in 2014 Robert Rubin, together with Martin Feldstein, argued that the Fed should be prepared to use higher interest rates as a tool to combat bubbles.

In a NYT review of Roger Lowenstein’s book on the Federal Reserve Board, Robert Rubin touts the virtues of the Fed’s independence from political control. He decries efforts to make the Fed more accountable to Congress.

While the Fed may not feel as though it must directly respond to Congress, that does not mean it is not responsive to political pressures. In the last thirty five years, it has maintained policies that have on average kept the unemployment rate almost a full percentage point above the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (0.5 percentage points excluding the Great Recession). By contrast, in the prior three decades the unemployment rate had averaged half a percentage point less than CBO’s estimate of the NAIRU.

Source: Baker and Bernstein, 2013.

The higher unemployment acts as an insurance policy against inflation. The higher unemployment kept millions of people from working and deprived tens of millions of workers of the bargaining power needed to secure real wage increases. While modestly higher inflation would be a matter of little concern to most workers (especially since it is being driven in part by higher wages), it would be very upsetting to the financial sector since the value of the debt they own would be reduced.

The financial industry has a grossly disproportionate influence on the Fed due to its design. They largely control the 12 district banks. In addition, the governors appointed by the president tend to be more responsive to the concerns of the financial industry than other sectors of the economy. It is certainly possible that if the Fed were not so tied to the financial industry, it would have paid more attention to the housing bubble as it was growing. The industry made huge amounts of money from the mortgages that fueled the bubble. (In this context, it is probably worth noting that Mr. Rubin made more than $100 million from his position as a top executive at Citigroup during the bubble years.)

For these reasons, the public may not be as happy about the Fed’s lack of accountability to democratically elected bodies as Mr. Rubin. Many might prefer a central bank that is concerned more about workers than bankers.

Addendum:

On this topic, it is probably worth noting that in 2014 Robert Rubin, together with Martin Feldstein, argued that the Fed should be prepared to use higher interest rates as a tool to combat bubbles.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone has seen the news stories about how Representative Paul Ryan, the leading candidate to be the next Speaker of the House, is a budget wonk. That should make everyone feel good, since we would all like to think a person in this position understands the ins and outs of the federal budget. But instead of telling us about how much Ryan knows about the budget (an issue on which reporters actually don’t have insight), how about telling us what Ryan says about the budget?

It is possible to say things about what Ryan says, since he has said a lot on this topic and some of it is very clear. In addition to wanting to privatize both Social Security and Medicare, Ryan has indicated that he essentially wants to shut down the federal government in the sense of taking away all of the money for the non-military portion of the budget.

This fact is one that is easy to find if a reporter is willing to do five minutes of research. Ryan directed the Congressional Budget Office to score his budget plans back in 2012. The score of his plan showed the non-Social Security, non-Medicare portion of the federal budget shrinking to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2050 (page 16).

This number is roughly equal to current spending on the military. Ryan has indicated that he does not want to see the military budget cut to any substantial degree. That leaves no money for the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, The Justice Department, infrastructure spending or anything else. Following Ryan’s plan, in 35 years we would have nothing left over after paying for the military.

Just to be clear, this was not some offhanded gaffe where Ryan might have misspoke. He supervised the CBO analysis. CBO doesn’t write-down numbers in a dark corner and then throw them up on their website to embarrass powerful members of Congress. As the document makes clear, they consulted with Ryan in writing the analysis to make sure that they were accurately capturing his program.

So what percent of people in this country know that the next Speaker of the House would like to permanently shut down most of the government? What percent even of elite educated policy types even know this fact? My guess is almost no one, we just know he is a policy wonk.

Everyone has seen the news stories about how Representative Paul Ryan, the leading candidate to be the next Speaker of the House, is a budget wonk. That should make everyone feel good, since we would all like to think a person in this position understands the ins and outs of the federal budget. But instead of telling us about how much Ryan knows about the budget (an issue on which reporters actually don’t have insight), how about telling us what Ryan says about the budget?

It is possible to say things about what Ryan says, since he has said a lot on this topic and some of it is very clear. In addition to wanting to privatize both Social Security and Medicare, Ryan has indicated that he essentially wants to shut down the federal government in the sense of taking away all of the money for the non-military portion of the budget.

This fact is one that is easy to find if a reporter is willing to do five minutes of research. Ryan directed the Congressional Budget Office to score his budget plans back in 2012. The score of his plan showed the non-Social Security, non-Medicare portion of the federal budget shrinking to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2050 (page 16).

This number is roughly equal to current spending on the military. Ryan has indicated that he does not want to see the military budget cut to any substantial degree. That leaves no money for the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, The Justice Department, infrastructure spending or anything else. Following Ryan’s plan, in 35 years we would have nothing left over after paying for the military.

Just to be clear, this was not some offhanded gaffe where Ryan might have misspoke. He supervised the CBO analysis. CBO doesn’t write-down numbers in a dark corner and then throw them up on their website to embarrass powerful members of Congress. As the document makes clear, they consulted with Ryan in writing the analysis to make sure that they were accurately capturing his program.

So what percent of people in this country know that the next Speaker of the House would like to permanently shut down most of the government? What percent even of elite educated policy types even know this fact? My guess is almost no one, we just know he is a policy wonk.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yep, it seems that China now has a gross debt equal to 43.2 percent of its GDP, according to the I.M.F. By comparison, the gross debt of the United States is over 104 percent. But, the NYT apparently thinks China has a big problem here.

This does matter, because insofar as the main problem with China’s economy is a lack of demand, it can be easily countered with additional government spending. Of course if the government were up against some sort of borrowing constraint due to an excessive debt burden, and inflationary concerns precluded the printing of money, then the route of deficit spending would not be available. However such constraints only appear to exist in the pages of the NYT, not in the real world.

Yep, it seems that China now has a gross debt equal to 43.2 percent of its GDP, according to the I.M.F. By comparison, the gross debt of the United States is over 104 percent. But, the NYT apparently thinks China has a big problem here.

This does matter, because insofar as the main problem with China’s economy is a lack of demand, it can be easily countered with additional government spending. Of course if the government were up against some sort of borrowing constraint due to an excessive debt burden, and inflationary concerns precluded the printing of money, then the route of deficit spending would not be available. However such constraints only appear to exist in the pages of the NYT, not in the real world.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

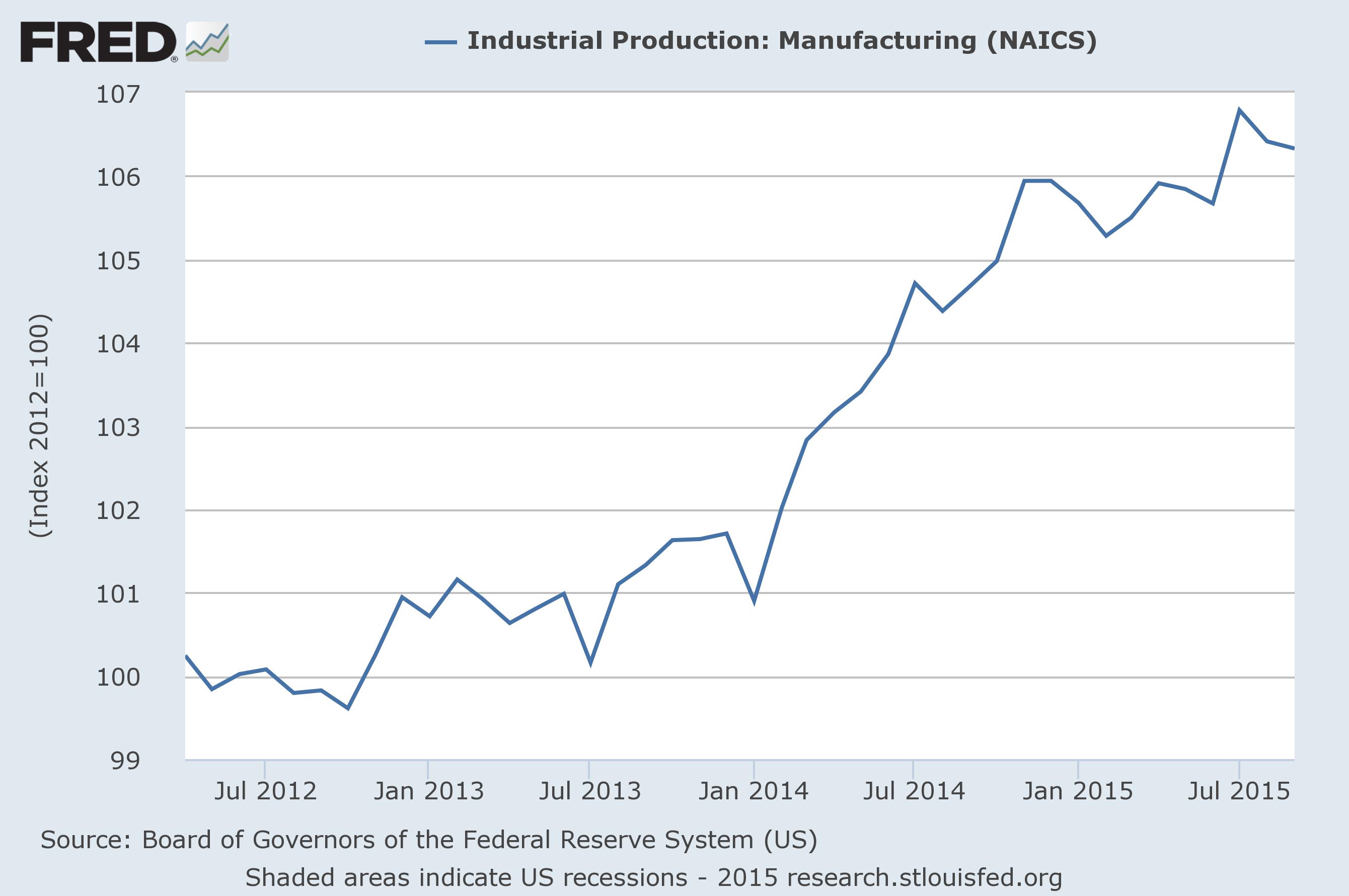

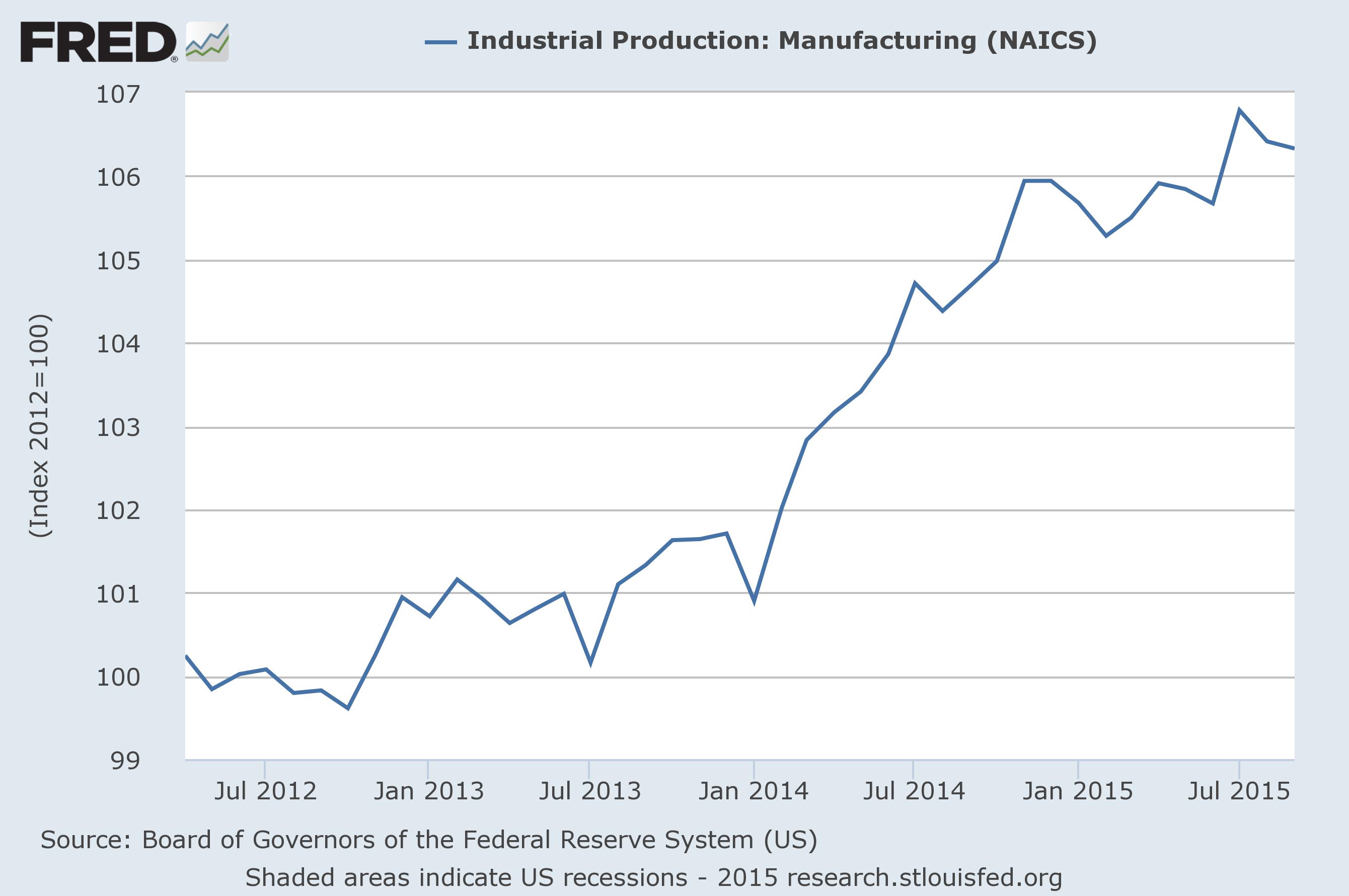

That seems to be the case these days. Last week the Federal Reserve Board reported that manufacturing output fell by 0.1 percent, the second consecutive monthly decline. The sector has been virtually flat since April, presumably reflecting the rise in the trade deficit.

This report seemed to go virtually unnoticed in places like the NYT and the Washington Post. Since the sector is still an important part of the economy, it might have been worth at least a small story.

That seems to be the case these days. Last week the Federal Reserve Board reported that manufacturing output fell by 0.1 percent, the second consecutive monthly decline. The sector has been virtually flat since April, presumably reflecting the rise in the trade deficit.

This report seemed to go virtually unnoticed in places like the NYT and the Washington Post. Since the sector is still an important part of the economy, it might have been worth at least a small story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión