Naturally, the paper had an editorial celebrating a deal on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In it they referred to the TPP as a free-trade deal and denounced opponents for appealing to “protectionist sentiment.” If we want to think about this one seriously, does the Post have any evidence whatsoever that the reduction in tariffs and other barriers in the TPP are economically larger than the increase in protectionist measures in the form of copyrights and patents? If so, it has never bothered to share this information with readers.

We get that the Washington Post likes patent and copyright protection. Its friends and advertisers benefit from these government granted monopolies. But, just because the Post likes patents and copyrights does not make them any less protectionist.

At a time like this it is hard not to remember when the Post claimed that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 because of NAFTA. (I have no idea why they chose 1987 as the base year.) The actual growth figure was 83 percent. Anyhow, the point is that these are not people who feel bound by the evidence in making their case for trade agreements.

Naturally, the paper had an editorial celebrating a deal on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In it they referred to the TPP as a free-trade deal and denounced opponents for appealing to “protectionist sentiment.” If we want to think about this one seriously, does the Post have any evidence whatsoever that the reduction in tariffs and other barriers in the TPP are economically larger than the increase in protectionist measures in the form of copyrights and patents? If so, it has never bothered to share this information with readers.

We get that the Washington Post likes patent and copyright protection. Its friends and advertisers benefit from these government granted monopolies. But, just because the Post likes patents and copyrights does not make them any less protectionist.

At a time like this it is hard not to remember when the Post claimed that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 because of NAFTA. (I have no idea why they chose 1987 as the base year.) The actual growth figure was 83 percent. Anyhow, the point is that these are not people who feel bound by the evidence in making their case for trade agreements.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

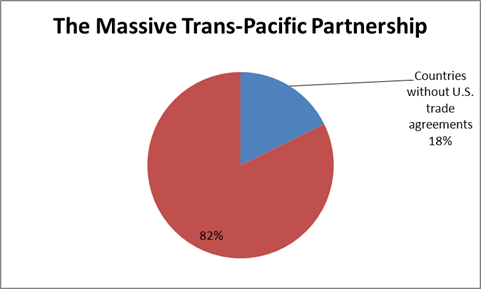

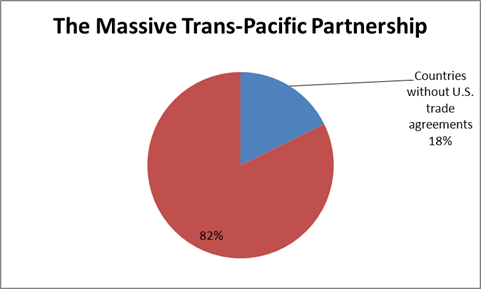

It is amazing how the elite media can be dragged along by their noses into accepting that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) can have a big impact on trade and growth. If I had a dollar for every time the deal was described as “massive” or that we were told what share of world trade will be covered by the TPP, I would be richer than Bill Gates. The reality is that the vast majority of the trade between the countries in the TPP is already covered by trade agreements as can be seen.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

We continue to hear superlatives even as the evidence suggests the trade impact will be trivial. For example, the NYT reported that U.S. tariffs on Japanese cars will be phased out over 30 years. Wow! The most optimistic growth estimates show a gain by 2027 of less than 0.4 percent, roughly two months of normal GDP growth.

This doesn’t mean that the TPP can’t have an impact. It will lock in a regulatory structure, the exact parameters of which are yet to be seen. We do know that the folks at the table came from places like General Electric and Monsanto, not the AFL-CIO and the Sierra Club. We also know that it will mean paying more for drugs and other patent and copyright protected material (forms of protection, whose negative impact is never included in growth projections), but we don’t yet know how much.

We also know that the Obama administration gave up an opportunity to include currency rules. This means that the trade deficit is likely to persist long into the future. This deficit has been a persistent source of gap in demand, leading to millions of lost jobs. We filled this demand in the 1990s with the stock bubble and in the last decade with the housing bubble. It seems the latest plan from the Fed is that we simply won’t fill the gap in this decade.

It is amazing how the elite media can be dragged along by their noses into accepting that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) can have a big impact on trade and growth. If I had a dollar for every time the deal was described as “massive” or that we were told what share of world trade will be covered by the TPP, I would be richer than Bill Gates. The reality is that the vast majority of the trade between the countries in the TPP is already covered by trade agreements as can be seen.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

We continue to hear superlatives even as the evidence suggests the trade impact will be trivial. For example, the NYT reported that U.S. tariffs on Japanese cars will be phased out over 30 years. Wow! The most optimistic growth estimates show a gain by 2027 of less than 0.4 percent, roughly two months of normal GDP growth.

This doesn’t mean that the TPP can’t have an impact. It will lock in a regulatory structure, the exact parameters of which are yet to be seen. We do know that the folks at the table came from places like General Electric and Monsanto, not the AFL-CIO and the Sierra Club. We also know that it will mean paying more for drugs and other patent and copyright protected material (forms of protection, whose negative impact is never included in growth projections), but we don’t yet know how much.

We also know that the Obama administration gave up an opportunity to include currency rules. This means that the trade deficit is likely to persist long into the future. This deficit has been a persistent source of gap in demand, leading to millions of lost jobs. We filled this demand in the 1990s with the stock bubble and in the last decade with the housing bubble. It seems the latest plan from the Fed is that we simply won’t fill the gap in this decade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Remember when then Federal Reserve Board Chair Ben Bernanke assured the public that the problems in the financial system will be restricted to the subprime market? This one ranks, along with some comments from and about Alan Greenspan, as one of the worst economic predictions of all time. In other words, the folks at the Fed really missed it.

This is worth remembering because it seems that the Fed is trying to get the excuse making going in advance for the next economic crisis. The NYT reported on a Fed conference where they expressed skepticism as to whether they could stop the next crisis.

There are a range of views presented, not all of them silly. (Using interest rates as the primary tool against bubbles is not a good strategy.) However the idea that the Fed is helpless against bubbles looks like some serious lowering of expectations.

The distortions created by the housing bubble were easy to see by anyone with open eyes. Residential construction as a share of GDP was hitting record levels even as demographics would have suggested the opposite. (Baby boomers were retiring or at least downsizing.) Consumption was hitting record highs as a share of disposable income, driven by housing bubble wealth. House prices had surged by 70 percent above inflation, after tracking the overall inflation rate for the prior century. And the bad loans were there en masse for anyone who cared to notice.

The Fed has a variety of tools but the most simple one is simply talking about a bubble. The financial markets will not ignore information (not a mumbled “irrational exuberance”) from the Fed as they showed in response to Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s comments about bubbles in the social media and biotech sectors.

There is no reason that the Fed should not have been issuing clear warnings (i.e. massive quantities of research) documenting the bubble from 2002 onward. The only cost to the Fed is a few researchers time, the potential savings are in the trillions. That seems a no-brainer. The Fed should have also been using its regulatory power to curb the issuance and sale of bad mortgages, but information is a good place to start.

Also, it is not plausible for an organization that argues an inflation target is important to say that information from the Fed has no impact on markets. It obviously believes otherwise.

Remember when then Federal Reserve Board Chair Ben Bernanke assured the public that the problems in the financial system will be restricted to the subprime market? This one ranks, along with some comments from and about Alan Greenspan, as one of the worst economic predictions of all time. In other words, the folks at the Fed really missed it.

This is worth remembering because it seems that the Fed is trying to get the excuse making going in advance for the next economic crisis. The NYT reported on a Fed conference where they expressed skepticism as to whether they could stop the next crisis.

There are a range of views presented, not all of them silly. (Using interest rates as the primary tool against bubbles is not a good strategy.) However the idea that the Fed is helpless against bubbles looks like some serious lowering of expectations.

The distortions created by the housing bubble were easy to see by anyone with open eyes. Residential construction as a share of GDP was hitting record levels even as demographics would have suggested the opposite. (Baby boomers were retiring or at least downsizing.) Consumption was hitting record highs as a share of disposable income, driven by housing bubble wealth. House prices had surged by 70 percent above inflation, after tracking the overall inflation rate for the prior century. And the bad loans were there en masse for anyone who cared to notice.

The Fed has a variety of tools but the most simple one is simply talking about a bubble. The financial markets will not ignore information (not a mumbled “irrational exuberance”) from the Fed as they showed in response to Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s comments about bubbles in the social media and biotech sectors.

There is no reason that the Fed should not have been issuing clear warnings (i.e. massive quantities of research) documenting the bubble from 2002 onward. The only cost to the Fed is a few researchers time, the potential savings are in the trillions. That seems a no-brainer. The Fed should have also been using its regulatory power to curb the issuance and sale of bad mortgages, but information is a good place to start.

Also, it is not plausible for an organization that argues an inflation target is important to say that information from the Fed has no impact on markets. It obviously believes otherwise.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Washington Post article on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) referred to President Obama’s assertion that the pact will boost growth. It would have been appropriate to point out that almost no economists support the claim that the pact will have a noticeable positive impact on growth.

The most favorable positive assessment comes from the Peterson Institute. It projects that the agreement would boost growth by 0.03 percentage points annually over the next dozen years. This would mean, for example, that if growth would have been 2.2 percent without the TPP, it would be 2.23 percent with the TPP. Other projections have been lower. For example, an analysis by the United States Department of Agriculture concluded that the gains would be too small to measure.

It is also worth noting that none of these studies took into account the negative impact on growth from the higher drug prices that would be the result of the stronger protectionist measures in the TPP. The United States currently spends more than $400 billion a year on prescription drugs. This amount will almost certainly increase in both the U.S. and elsewhere as a result of stronger patent and related protections in the TPP. Higher drug prices will pull money out of people’s pockets, leaving less to spend in other areas, thereby slowing growth.

For these reasons, it would have been useful to point out that President Obama is making a Trump-like claim in arguing that the TPP is a mechanism to increase economic growth. That is simply not a plausible story.

A Washington Post article on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) referred to President Obama’s assertion that the pact will boost growth. It would have been appropriate to point out that almost no economists support the claim that the pact will have a noticeable positive impact on growth.

The most favorable positive assessment comes from the Peterson Institute. It projects that the agreement would boost growth by 0.03 percentage points annually over the next dozen years. This would mean, for example, that if growth would have been 2.2 percent without the TPP, it would be 2.23 percent with the TPP. Other projections have been lower. For example, an analysis by the United States Department of Agriculture concluded that the gains would be too small to measure.

It is also worth noting that none of these studies took into account the negative impact on growth from the higher drug prices that would be the result of the stronger protectionist measures in the TPP. The United States currently spends more than $400 billion a year on prescription drugs. This amount will almost certainly increase in both the U.S. and elsewhere as a result of stronger patent and related protections in the TPP. Higher drug prices will pull money out of people’s pockets, leaving less to spend in other areas, thereby slowing growth.

For these reasons, it would have been useful to point out that President Obama is making a Trump-like claim in arguing that the TPP is a mechanism to increase economic growth. That is simply not a plausible story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, I’m sure it was just an error in editing, but come on. An NYT article on Germany on the 25th anniversary of the unification told readers:

“A new government report showed that gross domestic product per capita in eastern Germany has more than doubled in the past 25 years, but is still one-third the level in the western part of the country.”

I’m sure this is supposed to read that per capita GDP in former East Germany is one-third less than in the western part of country. Even this figure is somewhat misleading since the population of former East Germany is much older and more likely to be retirees than the rest of the country. There is probably still a difference in living standards among the working age populations, but nothing like what would be implied by this sentence.

As BTP readers know, I have my share of typos, but NYT has a bit more resources than my blog.

Note: It appears that even the one-third less number is an exaggeration as Robert Salzberg’s points out in his comment below.

Okay, I’m sure it was just an error in editing, but come on. An NYT article on Germany on the 25th anniversary of the unification told readers:

“A new government report showed that gross domestic product per capita in eastern Germany has more than doubled in the past 25 years, but is still one-third the level in the western part of the country.”

I’m sure this is supposed to read that per capita GDP in former East Germany is one-third less than in the western part of country. Even this figure is somewhat misleading since the population of former East Germany is much older and more likely to be retirees than the rest of the country. There is probably still a difference in living standards among the working age populations, but nothing like what would be implied by this sentence.

As BTP readers know, I have my share of typos, but NYT has a bit more resources than my blog.

Note: It appears that even the one-third less number is an exaggeration as Robert Salzberg’s points out in his comment below.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Elites like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). After all, it was designed to redistribute more income to sectors like the pharmaceutical industry, the financial industry, and the entertainment industry. The point is to use an international agreement to over-ride national and subnational governments that might pass laws to protect workers, consumers, or the environment.

In keeping with this spirit, the NYT touted the virtues of the TPP in an article describing President Obama’s efforts to conclude negotiations and get the deal through Congress:

“For President Obama, who cited the potential agreement during his address this week to the United Nations, success in a negotiating effort as old as his administration would be a legacy achievement. The proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership would liberalize trade and open markets among a dozen nations on both sides of the Pacific, from Canada to Chile and Japan to Australia, that account for about two-fifths of the world’s economic output.”

This paragraph tells readers that the NYT really really likes the TPP. After all, legacy achievement is pretty damn good. Does it beat out the Affordable Care Act, the Dodd-Frank financial reform, the stimulus that helped pull the economy out of the trough of the recession?

Apart from this editorializing, the rest of the paragraph is not true. While the countries in the TPP do account for two-fifths of the world’s economy, it is not clear that it would “liberalize trade” between most of the countries. The United States already has trade agreements with most of the other countries in the TPP, including Mexico, Canada, and Australia. In these cases, most of the barriers to trade have already been eliminated. Even the barriers with other countries are already low in most cases. This means that the TPP will do little to lower trade barriers.

On the other hand, a quite explicit purpose of the deal, as noted in this article, is to increase protectionism in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright protection. Perhaps the NYT likes these forms of protectionism, but they are still protectionism. This means that it is wrong to say that the TPP will liberalize trade. It is entirely possible that the net effect of the deal will be to increase the size of the trade barriers between the countries in the pact.

Elites like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). After all, it was designed to redistribute more income to sectors like the pharmaceutical industry, the financial industry, and the entertainment industry. The point is to use an international agreement to over-ride national and subnational governments that might pass laws to protect workers, consumers, or the environment.

In keeping with this spirit, the NYT touted the virtues of the TPP in an article describing President Obama’s efforts to conclude negotiations and get the deal through Congress:

“For President Obama, who cited the potential agreement during his address this week to the United Nations, success in a negotiating effort as old as his administration would be a legacy achievement. The proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership would liberalize trade and open markets among a dozen nations on both sides of the Pacific, from Canada to Chile and Japan to Australia, that account for about two-fifths of the world’s economic output.”

This paragraph tells readers that the NYT really really likes the TPP. After all, legacy achievement is pretty damn good. Does it beat out the Affordable Care Act, the Dodd-Frank financial reform, the stimulus that helped pull the economy out of the trough of the recession?

Apart from this editorializing, the rest of the paragraph is not true. While the countries in the TPP do account for two-fifths of the world’s economy, it is not clear that it would “liberalize trade” between most of the countries. The United States already has trade agreements with most of the other countries in the TPP, including Mexico, Canada, and Australia. In these cases, most of the barriers to trade have already been eliminated. Even the barriers with other countries are already low in most cases. This means that the TPP will do little to lower trade barriers.

On the other hand, a quite explicit purpose of the deal, as noted in this article, is to increase protectionism in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright protection. Perhaps the NYT likes these forms of protectionism, but they are still protectionism. This means that it is wrong to say that the TPP will liberalize trade. It is entirely possible that the net effect of the deal will be to increase the size of the trade barriers between the countries in the pact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT apparently thinks it has a big news story in its article telling readers that companies use temporary visas to bring over tech workers who learn skills and then transfer them to workplaces in India and other countries. The jobs are then shifted overseas to take advantage of lower cost labor.

This is one of the main goals of the trade agreements the United States has signed over the last three decades. The point has been to allow U.S. firms to take advantage of lower cost labor in the developing world. For the most part this has meant shifting manufacturing jobs, like those in the steel and auto industry. However the same logic of the gains from trade applies to more highly skilled jobs, like the tech jobs discussed in this article.

It’s not clear why the NYT thinks this is news, this is what is supposed to be the result of recent trade deals. Those who are displaced by foreign competition are obviously losers, but the rest of the economy benefits by having lower priced goods and services.

On net, workers who tend to be similar to the ones being displaced are losers when this displacement happens on a large scale due to the overall effect on wages. Those who are largely protected from foreign competition (by protectionist restrictions, not economic laws), like doctors and lawyers, benefit. It’s not clear why the NYT thinks it has news here, it is reporting on how trade policy has been designed to work.

The NYT apparently thinks it has a big news story in its article telling readers that companies use temporary visas to bring over tech workers who learn skills and then transfer them to workplaces in India and other countries. The jobs are then shifted overseas to take advantage of lower cost labor.

This is one of the main goals of the trade agreements the United States has signed over the last three decades. The point has been to allow U.S. firms to take advantage of lower cost labor in the developing world. For the most part this has meant shifting manufacturing jobs, like those in the steel and auto industry. However the same logic of the gains from trade applies to more highly skilled jobs, like the tech jobs discussed in this article.

It’s not clear why the NYT thinks this is news, this is what is supposed to be the result of recent trade deals. Those who are displaced by foreign competition are obviously losers, but the rest of the economy benefits by having lower priced goods and services.

On net, workers who tend to be similar to the ones being displaced are losers when this displacement happens on a large scale due to the overall effect on wages. Those who are largely protected from foreign competition (by protectionist restrictions, not economic laws), like doctors and lawyers, benefit. It’s not clear why the NYT thinks it has news here, it is reporting on how trade policy has been designed to work.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steve Mufson picked up the Washington elite’s quest to get more money for some of the country’s biggest corporations by telling readers that the Export-Import Bank is not really corporate welfare because it makes a profit.

“It isn’t much welfare; the bank has an excellent lending record — a default rate of 0.175 percent as of September 2014 and a 50 percent recovery rate on defaulted loans — and the appropriation for about $110 million covers administrative expenses.”

This displays the sort of basic confusion on economics that readers have come to expect from the Washington Post. The point is that the government is subsidizing loans to some of the largest companies in the country. By relying on the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, the Ex-Im Bank is allowing a small number of huge companies, who always account for the overwhelming majority of Ex-Im bank lending, to get loans at below the market rate. This is similar to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which allow mortgage holders to get mortgages at a below market rate by providing a government guarantee.

This is a clear subsidy outside of Washington Post land. If it serves a public purpose, for example promoting homeownership, then it is arguably a good policy. But the nonsense and name-calling being put forth to justify the Ex-Im bank hardly make the case.

Anyhow, since the honchos will undoubtedly keep pushing the Ex-Im Bank until Boeing gets its money, how about a compromise? Any company that gets below market interest loans as a result of Ex-Im bank subsidies has to agree not to pay its top executives more than 10 times the president’s salary ($400k) for a five year period. That’s a $4 million hard cap on all compensation. The company’s top execs and all board members sign a certification to this effect promising them 10 years hard time if they lie.

What do you say folks? Can the CEO of Boeing and GE get by on $4 million a year? There are jobs at stake, right?

Steve Mufson picked up the Washington elite’s quest to get more money for some of the country’s biggest corporations by telling readers that the Export-Import Bank is not really corporate welfare because it makes a profit.

“It isn’t much welfare; the bank has an excellent lending record — a default rate of 0.175 percent as of September 2014 and a 50 percent recovery rate on defaulted loans — and the appropriation for about $110 million covers administrative expenses.”

This displays the sort of basic confusion on economics that readers have come to expect from the Washington Post. The point is that the government is subsidizing loans to some of the largest companies in the country. By relying on the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, the Ex-Im Bank is allowing a small number of huge companies, who always account for the overwhelming majority of Ex-Im bank lending, to get loans at below the market rate. This is similar to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which allow mortgage holders to get mortgages at a below market rate by providing a government guarantee.

This is a clear subsidy outside of Washington Post land. If it serves a public purpose, for example promoting homeownership, then it is arguably a good policy. But the nonsense and name-calling being put forth to justify the Ex-Im bank hardly make the case.

Anyhow, since the honchos will undoubtedly keep pushing the Ex-Im Bank until Boeing gets its money, how about a compromise? Any company that gets below market interest loans as a result of Ex-Im bank subsidies has to agree not to pay its top executives more than 10 times the president’s salary ($400k) for a five year period. That’s a $4 million hard cap on all compensation. The company’s top execs and all board members sign a certification to this effect promising them 10 years hard time if they lie.

What do you say folks? Can the CEO of Boeing and GE get by on $4 million a year? There are jobs at stake, right?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yesterday, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump released his plan for changing the tax code. The basic story is that he would give big tax cuts across the board, with the largest tax cuts going to the wealthy. He assured everyone that it will be revenue neutral since it would lead to a huge spurt of economic growth. (His number was 6.0 percent, topping Jeb Bush’s 4.0 percent by two full percentage points.)

Many of the reports on the plan did note the growth assumption and pointed out that few, if any, economists took it seriously. As a practical matter, we have seen this one before. Ronald Reagan put in place a large tax cut in the 1980s and George W. Bush did the same in the last decade. You have to try very hard to find a positive growth effect from either. Certainly no one could make the case with a straight face that these sorts of proposals could even get us to Bush’s 4.0 percent number, much less Trump’s 6.0 percent.

But apart from what the tax cuts may or may not be able to do in terms of growth, there is also the matter of how the Federal Reserve Board would react. If that sounds strange to you then you should be very angry at the reporters at your favorite news outlet, because they should have been talking about this.

Suppose that Donald Trump’s tax cut really is the magic elixir that would get the economy to 6.0 percent annual growth. But what if the people at the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) don’t recognize this fact? Suppose the FOMC thinks the economy is still bound by the pre-Trump tax cut rules and believes that inflation will start to accelerate out of control if the unemployment rate falls much below its current 5.1 percent level.

In this case, we would expect to see the Fed raise interest rates sharply as they saw the Trump tax cuts boosting growth. Higher interest rates would slow house buying and new construction, discourage car sales, and put a crimp in both public and private investment. If the Fed raises interest rates high enough, it could fully offset the boost that Trump’s tax cut is giving to the economy. In this case, even though the Trump tax cuts might have been the best thing for the economy since the Internet (okay, better than the Internet), we wouldn’t see any dividend because the Fed would not allow it.

For this reason, the Fed’s likely response to a tax cut is a fundamental question that reporters should be asking. If the Fed is likely to simply slam on the brakes to offset any possible stimulus, then a tax plan will have little prospect of providing a growth dividend.

Since the press have been obsessing (rightly) over the possibility that the Fed is about to embark on a series of rate hikes, it would be reasonable to believe that someone would think to bring together the Fed’s interest rate policy and the candidate’s economic plans. Thus far it seems no reporters have discovered the connection.

Note: Typo corrected.

Yesterday, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump released his plan for changing the tax code. The basic story is that he would give big tax cuts across the board, with the largest tax cuts going to the wealthy. He assured everyone that it will be revenue neutral since it would lead to a huge spurt of economic growth. (His number was 6.0 percent, topping Jeb Bush’s 4.0 percent by two full percentage points.)

Many of the reports on the plan did note the growth assumption and pointed out that few, if any, economists took it seriously. As a practical matter, we have seen this one before. Ronald Reagan put in place a large tax cut in the 1980s and George W. Bush did the same in the last decade. You have to try very hard to find a positive growth effect from either. Certainly no one could make the case with a straight face that these sorts of proposals could even get us to Bush’s 4.0 percent number, much less Trump’s 6.0 percent.

But apart from what the tax cuts may or may not be able to do in terms of growth, there is also the matter of how the Federal Reserve Board would react. If that sounds strange to you then you should be very angry at the reporters at your favorite news outlet, because they should have been talking about this.

Suppose that Donald Trump’s tax cut really is the magic elixir that would get the economy to 6.0 percent annual growth. But what if the people at the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) don’t recognize this fact? Suppose the FOMC thinks the economy is still bound by the pre-Trump tax cut rules and believes that inflation will start to accelerate out of control if the unemployment rate falls much below its current 5.1 percent level.

In this case, we would expect to see the Fed raise interest rates sharply as they saw the Trump tax cuts boosting growth. Higher interest rates would slow house buying and new construction, discourage car sales, and put a crimp in both public and private investment. If the Fed raises interest rates high enough, it could fully offset the boost that Trump’s tax cut is giving to the economy. In this case, even though the Trump tax cuts might have been the best thing for the economy since the Internet (okay, better than the Internet), we wouldn’t see any dividend because the Fed would not allow it.

For this reason, the Fed’s likely response to a tax cut is a fundamental question that reporters should be asking. If the Fed is likely to simply slam on the brakes to offset any possible stimulus, then a tax plan will have little prospect of providing a growth dividend.

Since the press have been obsessing (rightly) over the possibility that the Fed is about to embark on a series of rate hikes, it would be reasonable to believe that someone would think to bring together the Fed’s interest rate policy and the candidate’s economic plans. Thus far it seems no reporters have discovered the connection.

Note: Typo corrected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión