This NYT article on various state bills calling for drug companies to reveal their spending on research for high-priced drugs might have been a good place to mention that we have alternatives to patent financing for prescription drug research. For example, the federal government already spends more than $30 billion a year on research through the National Institutes of Health. If this sum were doubled or tripled, it could likely replace the patent supported research now being done by the drug industry.

And, since the research was all paid for upfront, the great new drugs developed for cancer, AIDS, and other diseases could all be sold as generics. Then we would not face tough decisions about whether to pay for expensive drugs for people who need them. We also would have eliminated the incentive for drug companies to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

This NYT article on various state bills calling for drug companies to reveal their spending on research for high-priced drugs might have been a good place to mention that we have alternatives to patent financing for prescription drug research. For example, the federal government already spends more than $30 billion a year on research through the National Institutes of Health. If this sum were doubled or tripled, it could likely replace the patent supported research now being done by the drug industry.

And, since the research was all paid for upfront, the great new drugs developed for cancer, AIDS, and other diseases could all be sold as generics. Then we would not face tough decisions about whether to pay for expensive drugs for people who need them. We also would have eliminated the incentive for drug companies to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

You’ve got to admire those Silicon Valley boys, they hire one of President Obama’s top political advisers as a lobbyist, put out misleading studies on drivers’ pay, and now they are trying to get their drivers to lobby to reduce their own pay.

The context for the latter was their urging of their “partners” to come to a rally against New York Mayor Bill de Blasio’s decision to freeze the number of new cars for hire that Uber and other Internet based companies can put on the city’s streets. De Blasio was ostensibly putting in place this freeze to reduce congestion.

Whether or not the freeze is justified, one thing that is straightforward is that it would act to protect the earnings of existing Uber drivers in the same way that it would protect the earnings of the incumbent taxi industry. With fewer taxis on the road, there will be more passengers for each driver. This is likely to make an especially large difference for Uber drivers since its surge pricing model will lead to automatic fare increases when cars are in short supply.

This means that Uber was effectively asking these drivers to demand that the city cut their pay. I guess we’ll see if it works, maybe it really is a new economy.

You’ve got to admire those Silicon Valley boys, they hire one of President Obama’s top political advisers as a lobbyist, put out misleading studies on drivers’ pay, and now they are trying to get their drivers to lobby to reduce their own pay.

The context for the latter was their urging of their “partners” to come to a rally against New York Mayor Bill de Blasio’s decision to freeze the number of new cars for hire that Uber and other Internet based companies can put on the city’s streets. De Blasio was ostensibly putting in place this freeze to reduce congestion.

Whether or not the freeze is justified, one thing that is straightforward is that it would act to protect the earnings of existing Uber drivers in the same way that it would protect the earnings of the incumbent taxi industry. With fewer taxis on the road, there will be more passengers for each driver. This is likely to make an especially large difference for Uber drivers since its surge pricing model will lead to automatic fare increases when cars are in short supply.

This means that Uber was effectively asking these drivers to demand that the city cut their pay. I guess we’ll see if it works, maybe it really is a new economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

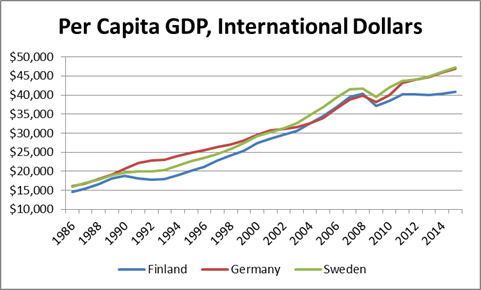

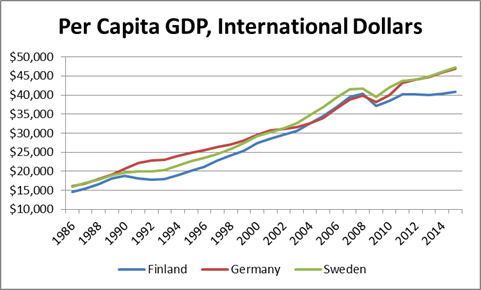

That is the conclusion that readers might draw from a piece by Neil Irwin in which he interviews Alexander Stubb, the Finnish finance minister, on the merits of the euro for Finland. Finland is often cited by euro critics because its economy is mired in recession even though, unlike Greece, it has always maintained low budget deficits and its government is not corrupt and highly efficient. The problem cited by critics (including me) is that the being in the euro prevent Finland from devaluing its currency to regain competitiveness.

Stubb dismisses the current weakness as a rough patch:

“You have to look at a longer time horizon. In his telling, the integration with Western Europe — of which the euro currency is a crucial element — deepened trade and diplomatic relations, making Finland both more powerful on the world stage and its industries better connected to the rest of the global economy. That made its people richer.

“‘In the early 1990s in the middle of a Finnish banking crisis and economic depression, we were a top 30 country in the world in per capita G.D.P.,’ he said. ‘Then we opened up; we became members of the E.U. Now we’re always up there in G.D.P. per capita or whatever other measure you look at with Sweden, Denmark, Australia and Canada.'”

Actually, if we look at a slightly longer time horizon, we would find that Finland was actually very close in per capita income to Sweden, Germany, and other rich countries in the 1980s before the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland’s per capita GDP was roughly 95 percent of the levels in Germany and Sweden. It fell sharply in the early 1990s but was already regaining ground rapidly by the mid-1990s, before the establishment of the euro. Since the recession Finland’s per capita GDP has fallen relative to both countries. It is now lower relative to Sweden, which is not in the euro, than it was at any point in the nineties, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Note: An earlier verison had a graph without years on the axis, as several comments notes, this has been corrected.

That is the conclusion that readers might draw from a piece by Neil Irwin in which he interviews Alexander Stubb, the Finnish finance minister, on the merits of the euro for Finland. Finland is often cited by euro critics because its economy is mired in recession even though, unlike Greece, it has always maintained low budget deficits and its government is not corrupt and highly efficient. The problem cited by critics (including me) is that the being in the euro prevent Finland from devaluing its currency to regain competitiveness.

Stubb dismisses the current weakness as a rough patch:

“You have to look at a longer time horizon. In his telling, the integration with Western Europe — of which the euro currency is a crucial element — deepened trade and diplomatic relations, making Finland both more powerful on the world stage and its industries better connected to the rest of the global economy. That made its people richer.

“‘In the early 1990s in the middle of a Finnish banking crisis and economic depression, we were a top 30 country in the world in per capita G.D.P.,’ he said. ‘Then we opened up; we became members of the E.U. Now we’re always up there in G.D.P. per capita or whatever other measure you look at with Sweden, Denmark, Australia and Canada.'”

Actually, if we look at a slightly longer time horizon, we would find that Finland was actually very close in per capita income to Sweden, Germany, and other rich countries in the 1980s before the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland’s per capita GDP was roughly 95 percent of the levels in Germany and Sweden. It fell sharply in the early 1990s but was already regaining ground rapidly by the mid-1990s, before the establishment of the euro. Since the recession Finland’s per capita GDP has fallen relative to both countries. It is now lower relative to Sweden, which is not in the euro, than it was at any point in the nineties, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Note: An earlier verison had a graph without years on the axis, as several comments notes, this has been corrected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

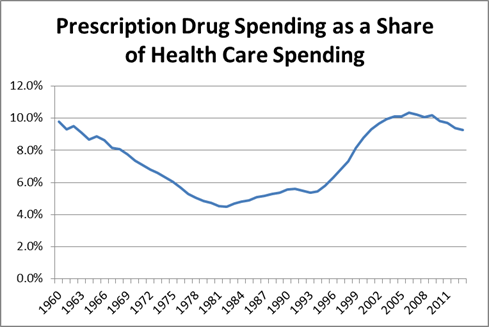

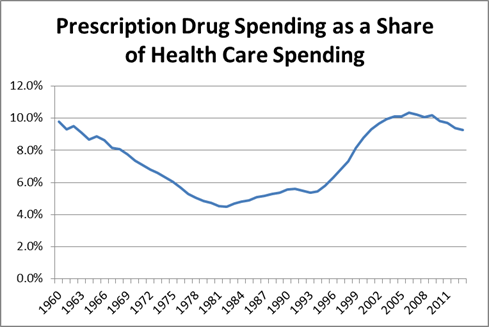

Those folks at the Wall Street Journal are really turning reality on its head. Today it ran a column by Robert Ingram, a former CEO of Glaxo Wellcome, complaining about efforts to pass “transparency” legislation in Massachusetts, New York, and a number of other states. This legislation would require drug companies to report their profits on certain expensive drugs as well as government funding that contributed to their development.

Ingram sees such laws as a prelude to price controls. He then warns readers:

“There is no surer way to bring pharmaceutical innovation to a halt in the U.S. than letting governments decide how much companies can charge for their products or harassing them into lower prices. It also represents a fundamental misunderstanding of how pharmaceutical research works. Scientific discoveries involve trying and failing, learning from those failures and trying again and again, often for years.”

Ingram bizarrely touts the “flowing pipeline of new wonder drugs spurred by a free market,” which he warns will be stopped by “government price controls.” This juxtaposition is bizarre, because patent monopolies are 180 degrees at odds with the free market. These monopolies are a government policy to provide incentives for innovation. Mr. Ingram obviously likes this policy, but that doesn’t make it the free market.

Of course there are other ways that the government can finance research and development, such as paying for it directly. It already does this to a large extent. At the encouragement of the pharmaceutical industry it spends more than $30 billion a year on mostly basic research conducted through the National Institutes of Health. It could double or triple the amount of direct funding (which could be contracted with private firms like Glaxo Wellcome) with the condition that all findings are placed in the public domain.

This would eliminate all the distortions associated with patent monopolies, such as patent-protected prices that are can be more than one hundred times as much as the free market price. This would eliminate all the ethical dilemmas about whether the government or private insurers should pay for expensive drugs like Sovaldi, since the drugs would be cheap. It would also eliminate the incentive to mislead doctors and the public about the safety and effectiveness of drugs in order to benefit from monopoly profits.

It would be great to have an honest debate about the best way to finance drug research. The first step is to stop conflating government granted patent monopolies with the free market.

One important point that Ingram gets wrong in this piece is his claim that, “Prescription drugs account for only about 10% of U.S. health-care spending, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This percentage has not changed since 1960 and is projected to remain the same for the next decade.”

While spending on drugs is roughly the same share of health care spending as it was in 1960, this is a sharp recovery from the level of the early 1980s, when it was close to 5 percent. Furthermore, spending on pharmaceuticals rose by more than 10.0 percent in 2014, which means that currently they are growing rapidly as a share of total health care spending.

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Those folks at the Wall Street Journal are really turning reality on its head. Today it ran a column by Robert Ingram, a former CEO of Glaxo Wellcome, complaining about efforts to pass “transparency” legislation in Massachusetts, New York, and a number of other states. This legislation would require drug companies to report their profits on certain expensive drugs as well as government funding that contributed to their development.

Ingram sees such laws as a prelude to price controls. He then warns readers:

“There is no surer way to bring pharmaceutical innovation to a halt in the U.S. than letting governments decide how much companies can charge for their products or harassing them into lower prices. It also represents a fundamental misunderstanding of how pharmaceutical research works. Scientific discoveries involve trying and failing, learning from those failures and trying again and again, often for years.”

Ingram bizarrely touts the “flowing pipeline of new wonder drugs spurred by a free market,” which he warns will be stopped by “government price controls.” This juxtaposition is bizarre, because patent monopolies are 180 degrees at odds with the free market. These monopolies are a government policy to provide incentives for innovation. Mr. Ingram obviously likes this policy, but that doesn’t make it the free market.

Of course there are other ways that the government can finance research and development, such as paying for it directly. It already does this to a large extent. At the encouragement of the pharmaceutical industry it spends more than $30 billion a year on mostly basic research conducted through the National Institutes of Health. It could double or triple the amount of direct funding (which could be contracted with private firms like Glaxo Wellcome) with the condition that all findings are placed in the public domain.

This would eliminate all the distortions associated with patent monopolies, such as patent-protected prices that are can be more than one hundred times as much as the free market price. This would eliminate all the ethical dilemmas about whether the government or private insurers should pay for expensive drugs like Sovaldi, since the drugs would be cheap. It would also eliminate the incentive to mislead doctors and the public about the safety and effectiveness of drugs in order to benefit from monopoly profits.

It would be great to have an honest debate about the best way to finance drug research. The first step is to stop conflating government granted patent monopolies with the free market.

One important point that Ingram gets wrong in this piece is his claim that, “Prescription drugs account for only about 10% of U.S. health-care spending, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This percentage has not changed since 1960 and is projected to remain the same for the next decade.”

While spending on drugs is roughly the same share of health care spending as it was in 1960, this is a sharp recovery from the level of the early 1980s, when it was close to 5 percent. Furthermore, spending on pharmaceuticals rose by more than 10.0 percent in 2014, which means that currently they are growing rapidly as a share of total health care spending.

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This one needs a really big “oy.” The lead headline of the Huffington Post tells readers that “child poverty higher now than great recession.” This is based on an AP story headlined “more U.S. children are living in poverty than during the great recession.” This article is in turn based on the annual Kids Count Data Book that is produced by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

It turns out that this is not quite the story as the second paragraph of the article indicates:

“Twenty-two percent of American children were living in poverty in 2013 compared with 18 percent in 2008, according to the latest Kids Count Data Book, with poverty rates nearly double among African-Americans and American Indians and problems most severe in South and Southwest.”

Note the comparison is with 2008, the beginning of the recession, not the trough of the recession in 2010. By any measure the recovery from this recession has been slow and weak. (It is hard to recover from recessions caused by bursting asset bubbles.)

Almost eight years after its onset we would still need another three million jobs to restore the prime age employment rate to its pre-crisis level. And median wages are still below their pre-crisis level. But the child poverty rate is at least moving in the right direction in the recovery, even if way too slowly. And even the pre-recession level was ridiculously high. Anyhow, the real story is bad enough, it’s not necessary to exaggerate.

This one needs a really big “oy.” The lead headline of the Huffington Post tells readers that “child poverty higher now than great recession.” This is based on an AP story headlined “more U.S. children are living in poverty than during the great recession.” This article is in turn based on the annual Kids Count Data Book that is produced by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

It turns out that this is not quite the story as the second paragraph of the article indicates:

“Twenty-two percent of American children were living in poverty in 2013 compared with 18 percent in 2008, according to the latest Kids Count Data Book, with poverty rates nearly double among African-Americans and American Indians and problems most severe in South and Southwest.”

Note the comparison is with 2008, the beginning of the recession, not the trough of the recession in 2010. By any measure the recovery from this recession has been slow and weak. (It is hard to recover from recessions caused by bursting asset bubbles.)

Almost eight years after its onset we would still need another three million jobs to restore the prime age employment rate to its pre-crisis level. And median wages are still below their pre-crisis level. But the child poverty rate is at least moving in the right direction in the recovery, even if way too slowly. And even the pre-recession level was ridiculously high. Anyhow, the real story is bad enough, it’s not necessary to exaggerate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I see that Brad takes issue with my prior post arguing that the bubble-driven recession of 2001 and the more recent one in 2008 were really bad news which could not be easily escaped.

“You need to rebalance, but competent policymakers can balance the economy up, near full employment, rather than balancing the economy down. And from late 2005 to the end of 2007 the balancing-up process was put in motion and, in fact, 3/4 accomplished.

“There is no reason why moving three million workers from pounding nails in Nevada and support occupations to making exports, building infrastructure, and serving as home-health aides and barefoot doctors needs to be associated with a lost decade and, apparently, permanently reduced employment. A lower value of the currency can boost exports. Loan guarantees and burden-sharing can get state governments into the infrastructure business. A surtax on the rich can employ a lot of home health aides and barefoot doctors. If these roads were foreclosed, they were foreclosed by the laws of American politics, not the laws of economics.

“And the lack of successful and rapid rebalancing–the weak post-2001 recovery–was also, overwhelmingly, a matter of choice: to use tax cuts rather than infrastructure and other social capital-building forms of spending on the government side, and to direct the dollar earnings of foreigners selling us imports into funding house construction rather than buying exports on the private-spending side.”

I would agree with this mostly, but say that it misses the point. (I disagree on the 3/4 accomplished part in the first paragraph, but that is secondary.) We do not have a political environment in which we can run deficits of the size needed to correct large imbalances, nor can we address chronic trade deficits by getting the dollar down. For this reason, bubbles are really bad news because when (not if) they burst we lack the ability to address the resulting shortfall in demand.

This is really simply stuff and that is a big problem in dealing with it. Economists want things to be difficult as do the liberal billionaires who fund economic research and policy analysis. Rather than trying to figure out a way to try to make it clear that we have to get the government to spend money or to drive down the value of the dollar, we will see tens of millions spent on developing new economic theory. Oh well, at least it will help to stimulate the economy.

I see that Brad takes issue with my prior post arguing that the bubble-driven recession of 2001 and the more recent one in 2008 were really bad news which could not be easily escaped.

“You need to rebalance, but competent policymakers can balance the economy up, near full employment, rather than balancing the economy down. And from late 2005 to the end of 2007 the balancing-up process was put in motion and, in fact, 3/4 accomplished.

“There is no reason why moving three million workers from pounding nails in Nevada and support occupations to making exports, building infrastructure, and serving as home-health aides and barefoot doctors needs to be associated with a lost decade and, apparently, permanently reduced employment. A lower value of the currency can boost exports. Loan guarantees and burden-sharing can get state governments into the infrastructure business. A surtax on the rich can employ a lot of home health aides and barefoot doctors. If these roads were foreclosed, they were foreclosed by the laws of American politics, not the laws of economics.

“And the lack of successful and rapid rebalancing–the weak post-2001 recovery–was also, overwhelmingly, a matter of choice: to use tax cuts rather than infrastructure and other social capital-building forms of spending on the government side, and to direct the dollar earnings of foreigners selling us imports into funding house construction rather than buying exports on the private-spending side.”

I would agree with this mostly, but say that it misses the point. (I disagree on the 3/4 accomplished part in the first paragraph, but that is secondary.) We do not have a political environment in which we can run deficits of the size needed to correct large imbalances, nor can we address chronic trade deficits by getting the dollar down. For this reason, bubbles are really bad news because when (not if) they burst we lack the ability to address the resulting shortfall in demand.

This is really simply stuff and that is a big problem in dealing with it. Economists want things to be difficult as do the liberal billionaires who fund economic research and policy analysis. Rather than trying to figure out a way to try to make it clear that we have to get the government to spend money or to drive down the value of the dollar, we will see tens of millions spent on developing new economic theory. Oh well, at least it will help to stimulate the economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Uber is once again dipping its toe into the world of innovative social science. Folks may recall that earlier this year it commissioned Alan Krueger, one of the country’s leading labor economists and formerly President Obama’s chief economist, to do an analysis of Uber drivers’ pay. While Uber shared data with Kreuger on drivers’ gross receipts, it did not share data on miles driven. This meant that Krueger was left comparing the gross receipts of its drivers with the net income of cab drivers in the incumbent taxi industry. The gross receipts do not deduct costs borne by the driver, such as gas, depreciation on the car, and insurance.

Not surprisingly, the gross receipts of Uber drivers were higher than the net income of drivers for the incumbent tax industry. It’s not clear if this comparison would hold up if Krueger had done an apples to apples comparison where he deducted expenses for Uber drivers, but he couldn’t do this, since Uber didn’t give him the miles data.

In keeping with this approach to social science Uber has commissioned a new study that purports to show that it provides better service to minorities than the incumbent taxi industry. The test was to have someone order an Uber car in a heavily minority community on their smartphone, and compare the time it takes to get their pickup with the time it takes someone calling for a taxi from an incumbent company. Uber found that its service was markedly faster than the service of the incumbent industry.

Before anyone celebrates over this finding that Uber has eliminated or at least reduced discrimination in taxi service, a bit of thinking is required. To order an Uber car it is necessary to have both a smart phone and a credit card. A substantial portion of the low income and minority populations lack one or the other.

The Uber study effectively asked the question of whether Uber provides better service to a screened portion of the minority community, using a screening mechanism that is likely to weed out the poorer portion of this community. Furthermore, Uber knew of this screening, since it is how their cars are summoned. The incumbent taxi companies in its study did not know of the screening.

If we think that discrimination against minorities is a mixture of race, ethnicity, and class, the Uber study effectively used a screening mechanism that largely eliminated the class aspect of the matter, at least for the Uber drivers. In this context, the result is not very surprising.

CEPR is proposing that Uber finance a study where we compare the amount of time it takes people in minority communities to get an Uber car or a taxi ordered from an incumbent service, where the passenger does not have a credit card and orders over the phone. It will be interesting to see what we find.

Uber is once again dipping its toe into the world of innovative social science. Folks may recall that earlier this year it commissioned Alan Krueger, one of the country’s leading labor economists and formerly President Obama’s chief economist, to do an analysis of Uber drivers’ pay. While Uber shared data with Kreuger on drivers’ gross receipts, it did not share data on miles driven. This meant that Krueger was left comparing the gross receipts of its drivers with the net income of cab drivers in the incumbent taxi industry. The gross receipts do not deduct costs borne by the driver, such as gas, depreciation on the car, and insurance.

Not surprisingly, the gross receipts of Uber drivers were higher than the net income of drivers for the incumbent tax industry. It’s not clear if this comparison would hold up if Krueger had done an apples to apples comparison where he deducted expenses for Uber drivers, but he couldn’t do this, since Uber didn’t give him the miles data.

In keeping with this approach to social science Uber has commissioned a new study that purports to show that it provides better service to minorities than the incumbent taxi industry. The test was to have someone order an Uber car in a heavily minority community on their smartphone, and compare the time it takes to get their pickup with the time it takes someone calling for a taxi from an incumbent company. Uber found that its service was markedly faster than the service of the incumbent industry.

Before anyone celebrates over this finding that Uber has eliminated or at least reduced discrimination in taxi service, a bit of thinking is required. To order an Uber car it is necessary to have both a smart phone and a credit card. A substantial portion of the low income and minority populations lack one or the other.

The Uber study effectively asked the question of whether Uber provides better service to a screened portion of the minority community, using a screening mechanism that is likely to weed out the poorer portion of this community. Furthermore, Uber knew of this screening, since it is how their cars are summoned. The incumbent taxi companies in its study did not know of the screening.

If we think that discrimination against minorities is a mixture of race, ethnicity, and class, the Uber study effectively used a screening mechanism that largely eliminated the class aspect of the matter, at least for the Uber drivers. In this context, the result is not very surprising.

CEPR is proposing that Uber finance a study where we compare the amount of time it takes people in minority communities to get an Uber car or a taxi ordered from an incumbent service, where the passenger does not have a credit card and orders over the phone. It will be interesting to see what we find.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what millions of readers are asking after reading a NYT article on the fallout from Germany’s hardline in negotiations with Greece over its debt. The piece noted the lukewarm support given to Greece from France and Italy. It told readers:

“France and Italy struggle with some of the same problems as Greece: low growth, youth unemployment, rigid labor markets, bloated state bureaucracies and social welfare systems too generous now, when people live longer, to be supported by current revenue.”

It’s hard to see the basis for this assertion. According to the I.M.F., France has a structural budget deficit of 2.0 percent of GDP, Italy’s structural deficit is just 0.3 percent of GDP. Deficits of this size could be sustained indefinitely.

Both countries are running larger actual deficits at present because their economies are operating below full employment, even by the I.M.F.’s measure. (This measure is based on averaging recent output levels, so that a prolonged downturn will imply a lower level of potential output.) This suggests that the main source of budget problems for France and Italy is the contractionary fiscal policies being imposed on the euro zone by Germany and the European Central Bank, not excessive welfare state spending.

That’s what millions of readers are asking after reading a NYT article on the fallout from Germany’s hardline in negotiations with Greece over its debt. The piece noted the lukewarm support given to Greece from France and Italy. It told readers:

“France and Italy struggle with some of the same problems as Greece: low growth, youth unemployment, rigid labor markets, bloated state bureaucracies and social welfare systems too generous now, when people live longer, to be supported by current revenue.”

It’s hard to see the basis for this assertion. According to the I.M.F., France has a structural budget deficit of 2.0 percent of GDP, Italy’s structural deficit is just 0.3 percent of GDP. Deficits of this size could be sustained indefinitely.

Both countries are running larger actual deficits at present because their economies are operating below full employment, even by the I.M.F.’s measure. (This measure is based on averaging recent output levels, so that a prolonged downturn will imply a lower level of potential output.) This suggests that the main source of budget problems for France and Italy is the contractionary fiscal policies being imposed on the euro zone by Germany and the European Central Bank, not excessive welfare state spending.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Just after announcing his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination Scott Walker denounced the left for not having any real ideas for workers. According to Walker:

“They’ve just got really lame ideas, things like the minimum wage. Instead of focusing on that, we need to talk about how we give people the skills and the education, the qualifications they need to take on careers that pay far more than minimum wage.”

In his Washington Post “The Fix” column, Philip Bump largely endorsed this perspective.

“If the purpose the minimum wage is meant to serve is to lift people out of poverty, Pew points out that Walker’s right: Most minimum wages aren’t high enough to do that. The minimum wage is indeed lame, in the sense that it’s relatively impotent. Earning a minimum wage in 2014 was enough for a single person not to live in poverty, but not anyone with a family — and not everywhere across the country.”

There are a few points worth noting here. First, “the left” has many ideas for helping workers other than just the minimum wage. For example, many on the left have pushed for a full employment policy, which would mean having a Federal Reserve Board policy that allows the unemployment rate to continue to fall until there is clear evidence of inflation rather than preemptively raising interest rates to slow growth. It would also mean having trade policies designed to reduce the trade deficit (i.e. a lower valued dollar) which would provide a strong boost to jobs. It would also mean spending on infrastructure and education, which would also help to create jobs and have long-term growth benefits.

The left also favors policies that allow workers who want to be represented by unions to organize. This has a well known impact on wages, especially for less educated workers.

As far the denunciation of the minimum wage as “lame,” this is a policy that could put thousands of dollars a year into the pockets of low wage workers. For arithmetic fans, a three dollar an hour increase in the minimum wage would mean $6,000 a year for a full year worker. Since Bump seems to prefer per household measures to per worker measures, if a household has two workers earning near the minimum wage for a total of 3000 hours a year, a three dollar increase would imply $9,000 in additional income. It’s unlikely these people would think of the minimum wage as lame.

The last point is that Bump apparently doesn’t realize that Walker’s focus on skills and education are not new and are also shared by the left. The left has long led the way in pushing for public support for improved education. Even now, President Obama has put proposals forward for universal pre-K education and reducing the cost of college. Unions have not only supported education in the public sector, they routinely require training and upskilling of workers in their contracts.

If Walker has some new ideas on skills and education, then it would be worth hearing them, but Bump gives no indication that Walker did anything other than say the words as a way to denounce the left. In short, if Bump had more knowledge about history and current politics he would not join Walker in his name calling.

Addendum

It is worth noting that as governor of Wisconsin, Walker has targeted unions, trying to weaken them in both the public and private sectors. He has also attacked the University of Wisconsin, one of the top public unversities in the country. Insofar as he is committed to a path of upward mobility for workers, these actions go in the opposite direction.

Just after announcing his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination Scott Walker denounced the left for not having any real ideas for workers. According to Walker:

“They’ve just got really lame ideas, things like the minimum wage. Instead of focusing on that, we need to talk about how we give people the skills and the education, the qualifications they need to take on careers that pay far more than minimum wage.”

In his Washington Post “The Fix” column, Philip Bump largely endorsed this perspective.

“If the purpose the minimum wage is meant to serve is to lift people out of poverty, Pew points out that Walker’s right: Most minimum wages aren’t high enough to do that. The minimum wage is indeed lame, in the sense that it’s relatively impotent. Earning a minimum wage in 2014 was enough for a single person not to live in poverty, but not anyone with a family — and not everywhere across the country.”

There are a few points worth noting here. First, “the left” has many ideas for helping workers other than just the minimum wage. For example, many on the left have pushed for a full employment policy, which would mean having a Federal Reserve Board policy that allows the unemployment rate to continue to fall until there is clear evidence of inflation rather than preemptively raising interest rates to slow growth. It would also mean having trade policies designed to reduce the trade deficit (i.e. a lower valued dollar) which would provide a strong boost to jobs. It would also mean spending on infrastructure and education, which would also help to create jobs and have long-term growth benefits.

The left also favors policies that allow workers who want to be represented by unions to organize. This has a well known impact on wages, especially for less educated workers.

As far the denunciation of the minimum wage as “lame,” this is a policy that could put thousands of dollars a year into the pockets of low wage workers. For arithmetic fans, a three dollar an hour increase in the minimum wage would mean $6,000 a year for a full year worker. Since Bump seems to prefer per household measures to per worker measures, if a household has two workers earning near the minimum wage for a total of 3000 hours a year, a three dollar increase would imply $9,000 in additional income. It’s unlikely these people would think of the minimum wage as lame.

The last point is that Bump apparently doesn’t realize that Walker’s focus on skills and education are not new and are also shared by the left. The left has long led the way in pushing for public support for improved education. Even now, President Obama has put proposals forward for universal pre-K education and reducing the cost of college. Unions have not only supported education in the public sector, they routinely require training and upskilling of workers in their contracts.

If Walker has some new ideas on skills and education, then it would be worth hearing them, but Bump gives no indication that Walker did anything other than say the words as a way to denounce the left. In short, if Bump had more knowledge about history and current politics he would not join Walker in his name calling.

Addendum

It is worth noting that as governor of Wisconsin, Walker has targeted unions, trying to weaken them in both the public and private sectors. He has also attacked the University of Wisconsin, one of the top public unversities in the country. Insofar as he is committed to a path of upward mobility for workers, these actions go in the opposite direction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a major piece describing what it called a “global competition” by oil producers to stay in business even as prices remain low. The piece seems to imply that the strategy of Saudi Arabia in this competition is to pump enough oil to keep prices low, thereby driving out competitors. They would then raise their prices once the competition is gone.

This strategy does not make sense. A prolonged period of low prices may push some of their competitors into bankruptcy, like Continental Resources, the fracking company at the center of the piece, but the oil would still be there. This means that if prices rose enough to make shale oil profitable again, then new competitors will buy up the land and the equipment of the bankrupt companies and start producing oil again. While this process will take some time, it is at most a matter of a couple of years and quite possibly considerably less.

Given the current situation in the oil market, Saudi Arabia can likely have a large market share or can have high prices. There is not a plausible scenario in which it can have both.

The Washington Post had a major piece describing what it called a “global competition” by oil producers to stay in business even as prices remain low. The piece seems to imply that the strategy of Saudi Arabia in this competition is to pump enough oil to keep prices low, thereby driving out competitors. They would then raise their prices once the competition is gone.

This strategy does not make sense. A prolonged period of low prices may push some of their competitors into bankruptcy, like Continental Resources, the fracking company at the center of the piece, but the oil would still be there. This means that if prices rose enough to make shale oil profitable again, then new competitors will buy up the land and the equipment of the bankrupt companies and start producing oil again. While this process will take some time, it is at most a matter of a couple of years and quite possibly considerably less.

Given the current situation in the oil market, Saudi Arabia can likely have a large market share or can have high prices. There is not a plausible scenario in which it can have both.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión