In a NYT column Steve Rattner argues that the conditions being imposed on Greece by Germany as a condition of its bailout are for its own good. While Greece undoubtedly needs to reform its economy in many ways, Rattner ignores the extent to which austerity, both within the country and the euro zone as a whole, have worsened Greece’s economy. This is both true in a macro sense, in that cuts in government spending and increased taxes reduce GDP and employment, but also the resulting depression worsens other problems, like the public pension system.

Rattner includes a table showing that pensions in Greece are 16.2 percent of GDP, the highest in Europe. However pension spending as a share of GDP has risen sharply as a result of the downturn. In 2007, according to the OECD pension spending in Greece was 12.1 percent of GDP, less than France’s 12.5 percent and Italy’s 14.0 percent. In fact, Greece’s pension spending was not very much larger as a share of GDP than Germany’s 10.6 percent.

Since GDP has contracted by more than 25 percent, the ratio of pension spending to GDP would rise by roughly a third if it had stayed constant. (Pensions have actually been cut sharply under previous austerity programs.) The surge in unemployment, now over 25 percent, has also raised pension costs. Many people who would prefer to be working instead retired early and started collecting their pensions because they couldn’t find jobs.

This is a direct result of the austerity that Germany has imposed on Greece and one reason why the Greeks are not as appreciative of Germany as Rattner thinks they should be.

In a NYT column Steve Rattner argues that the conditions being imposed on Greece by Germany as a condition of its bailout are for its own good. While Greece undoubtedly needs to reform its economy in many ways, Rattner ignores the extent to which austerity, both within the country and the euro zone as a whole, have worsened Greece’s economy. This is both true in a macro sense, in that cuts in government spending and increased taxes reduce GDP and employment, but also the resulting depression worsens other problems, like the public pension system.

Rattner includes a table showing that pensions in Greece are 16.2 percent of GDP, the highest in Europe. However pension spending as a share of GDP has risen sharply as a result of the downturn. In 2007, according to the OECD pension spending in Greece was 12.1 percent of GDP, less than France’s 12.5 percent and Italy’s 14.0 percent. In fact, Greece’s pension spending was not very much larger as a share of GDP than Germany’s 10.6 percent.

Since GDP has contracted by more than 25 percent, the ratio of pension spending to GDP would rise by roughly a third if it had stayed constant. (Pensions have actually been cut sharply under previous austerity programs.) The surge in unemployment, now over 25 percent, has also raised pension costs. Many people who would prefer to be working instead retired early and started collecting their pensions because they couldn’t find jobs.

This is a direct result of the austerity that Germany has imposed on Greece and one reason why the Greeks are not as appreciative of Germany as Rattner thinks they should be.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As they say at the Post, don’t let the data bother you, or so it would seem with yet another article bemoaning the lack of consumption. The proximate cause was a Commerce Department report showing weaker retail sales in June after a big jump in May. The piece explained to readers:

“The figures suggest that Americans are still reluctant to spend freely, possibly restrained by memories of the Great Recession.

“‘Household caution still appears to be holding back a more rapid pace of spending growth,’ Michael Feroli, an economist at JPMorgan Chase, said in a note to clients.”

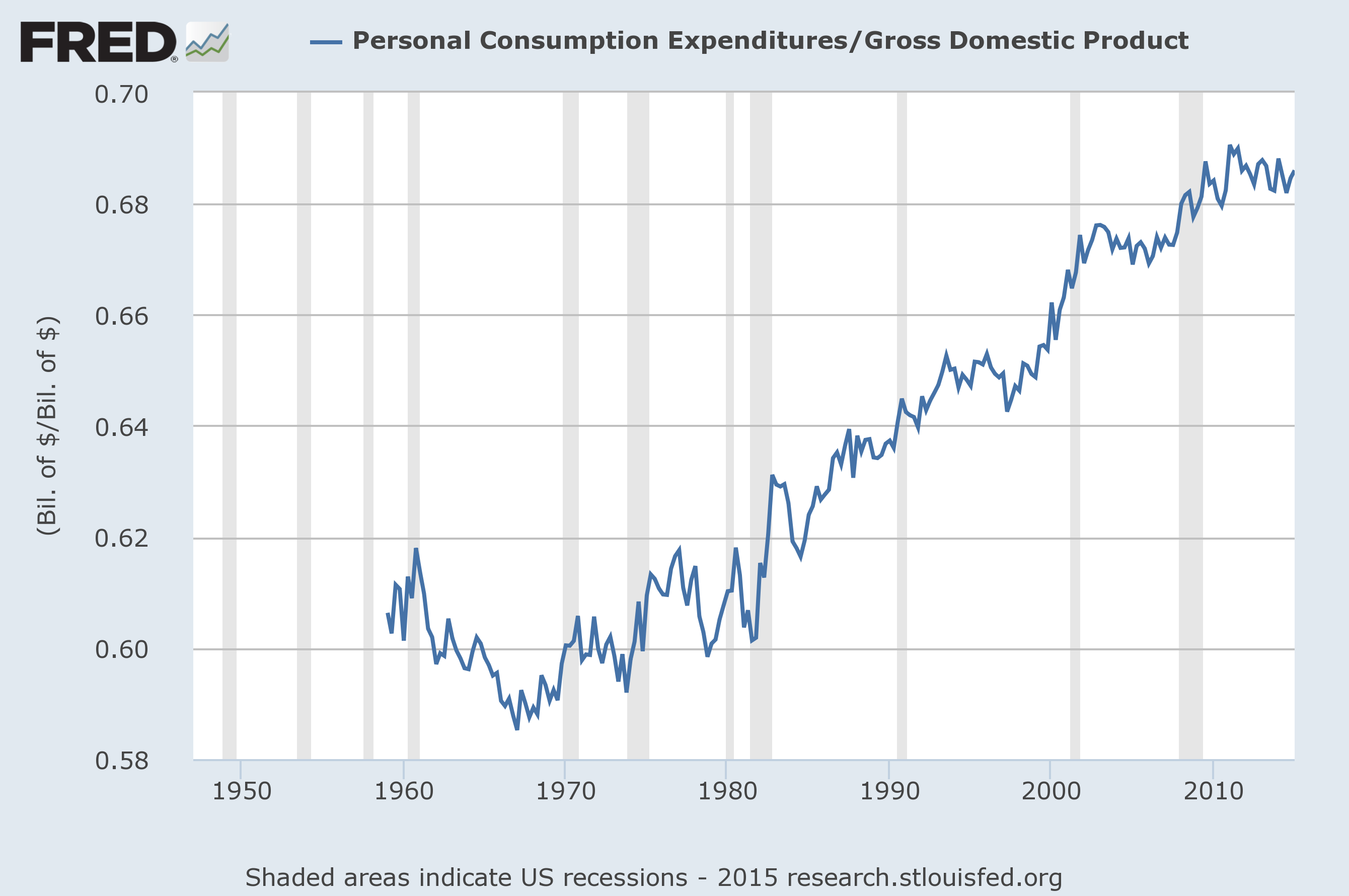

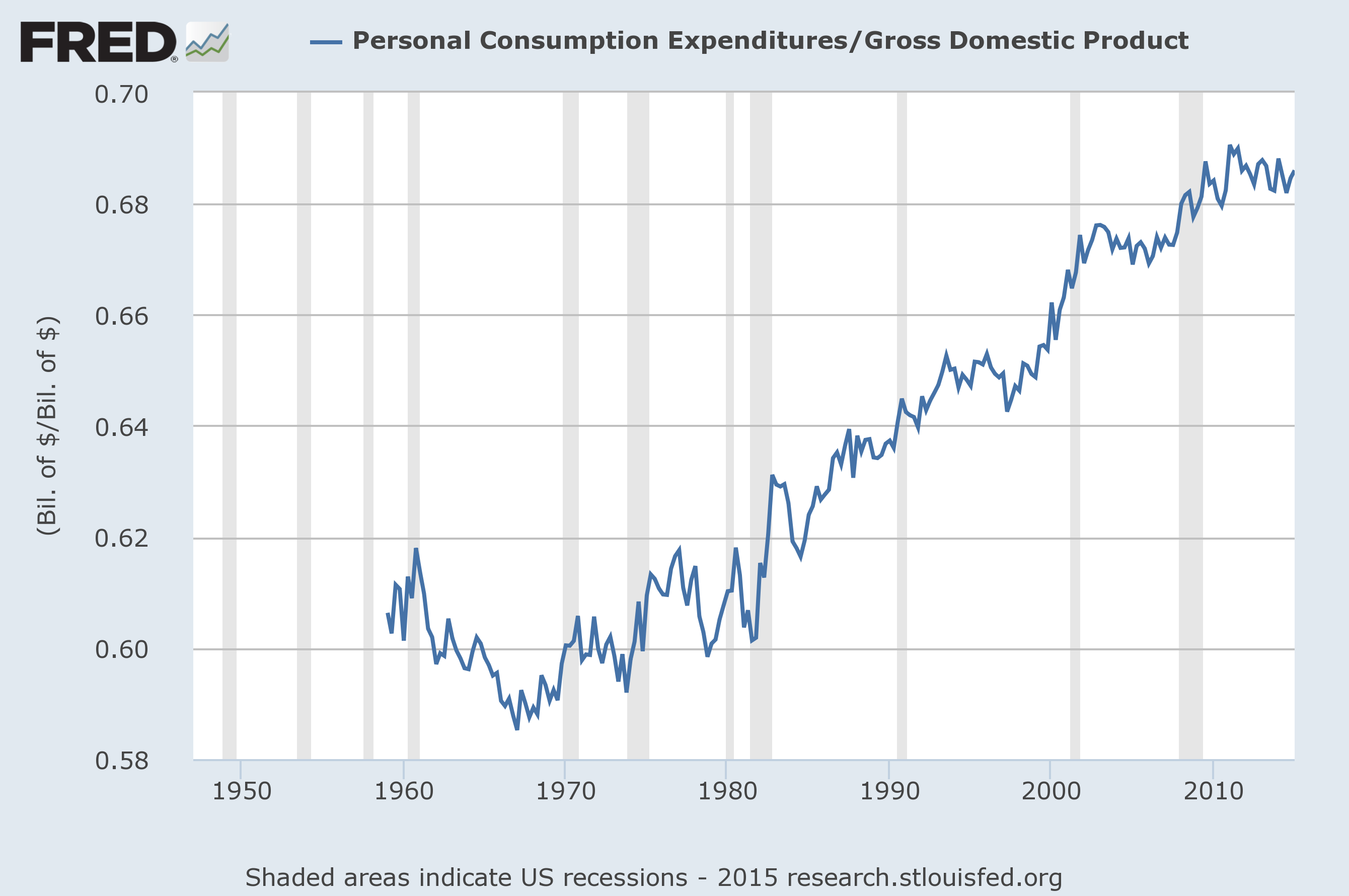

Here’s the slightly longer term picture.

For the record, there is no economist who wants to argue that the consumption share of GDP should continue to rise. The logical implication of such an argument is that investment, government spending, and net exports would continue to decline as a share of GDP. So we should look at levels, not changes here. And the level is actually higher than it was before consumers were scarred by memories of the Great Recession.

Btw, the folks who think that people need to save more for retirement, which include me, think that consumption is too high relative to income, not too low. That is definitional. Savings are the income that is not consumed.

As they say at the Post, don’t let the data bother you, or so it would seem with yet another article bemoaning the lack of consumption. The proximate cause was a Commerce Department report showing weaker retail sales in June after a big jump in May. The piece explained to readers:

“The figures suggest that Americans are still reluctant to spend freely, possibly restrained by memories of the Great Recession.

“‘Household caution still appears to be holding back a more rapid pace of spending growth,’ Michael Feroli, an economist at JPMorgan Chase, said in a note to clients.”

Here’s the slightly longer term picture.

For the record, there is no economist who wants to argue that the consumption share of GDP should continue to rise. The logical implication of such an argument is that investment, government spending, and net exports would continue to decline as a share of GDP. So we should look at levels, not changes here. And the level is actually higher than it was before consumers were scarred by memories of the Great Recession.

Btw, the folks who think that people need to save more for retirement, which include me, think that consumption is too high relative to income, not too low. That is definitional. Savings are the income that is not consumed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We’ve been hearing a lot about pensions in Greece lately. These have been a major target of the creditors in their negotiations with Greece. According to a recent article in the New York Times, 60 percent of Greeks receive a pension of less than $9,500 a year. An article in today’s Washington Post may lead people to ask what sort of pensions the top officials at the European Central Bank (ECB) get.

The article briefly recounts how Greece and other crisis countries got themselves into difficulties. The piece includes this strange line:

“The tipping point, though, came in 2010, when markets realized how much these governments now needed to borrow to make up for their bad economies.”

Actually it was not so much a market realization as a statement by the ECB that it was not committed to standing behind the sovereign debt of euro zone members. This led to the sudden realization that the bonds issued by these countries could default.

The fact that serious imbalances were building within the euro zone should not have been difficult for numerate people to recognize. Most of the crisis countries had persistently large current account deficits. (Italy is the major exception.) Portugal’s peaked at 9.5 percent of GDP in 2008, Spain’s at 10.5 percent, and Greece’s at 13.9 percent. These are the sorts of current account deficits that one would expect to see in a fast growing developing country like China (of yeah, they have a large trade surplus), not relatively wealthy countries that are not growing especially rapidly.

This should have led a bank that had the responsibility to maintain financial stability to take steps to try to reverse these imbalances, for example, by dampening the flows of credit that were sustaining it. However the ECB largely ignored the imbalances. When the first ECB president, Jean-Claude Trichet retired in the middle of the crisis in 2011, he patted himself on the back for keeping inflation under the bank’s 2.0 percent target.

Since it is apparently possible to take away the pensions that Greek people spent their life working for, some people may want to know if its possible to take back the much higher pensions earned by top officials at the ECB.

We’ve been hearing a lot about pensions in Greece lately. These have been a major target of the creditors in their negotiations with Greece. According to a recent article in the New York Times, 60 percent of Greeks receive a pension of less than $9,500 a year. An article in today’s Washington Post may lead people to ask what sort of pensions the top officials at the European Central Bank (ECB) get.

The article briefly recounts how Greece and other crisis countries got themselves into difficulties. The piece includes this strange line:

“The tipping point, though, came in 2010, when markets realized how much these governments now needed to borrow to make up for their bad economies.”

Actually it was not so much a market realization as a statement by the ECB that it was not committed to standing behind the sovereign debt of euro zone members. This led to the sudden realization that the bonds issued by these countries could default.

The fact that serious imbalances were building within the euro zone should not have been difficult for numerate people to recognize. Most of the crisis countries had persistently large current account deficits. (Italy is the major exception.) Portugal’s peaked at 9.5 percent of GDP in 2008, Spain’s at 10.5 percent, and Greece’s at 13.9 percent. These are the sorts of current account deficits that one would expect to see in a fast growing developing country like China (of yeah, they have a large trade surplus), not relatively wealthy countries that are not growing especially rapidly.

This should have led a bank that had the responsibility to maintain financial stability to take steps to try to reverse these imbalances, for example, by dampening the flows of credit that were sustaining it. However the ECB largely ignored the imbalances. When the first ECB president, Jean-Claude Trichet retired in the middle of the crisis in 2011, he patted himself on the back for keeping inflation under the bank’s 2.0 percent target.

Since it is apparently possible to take away the pensions that Greek people spent their life working for, some people may want to know if its possible to take back the much higher pensions earned by top officials at the ECB.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

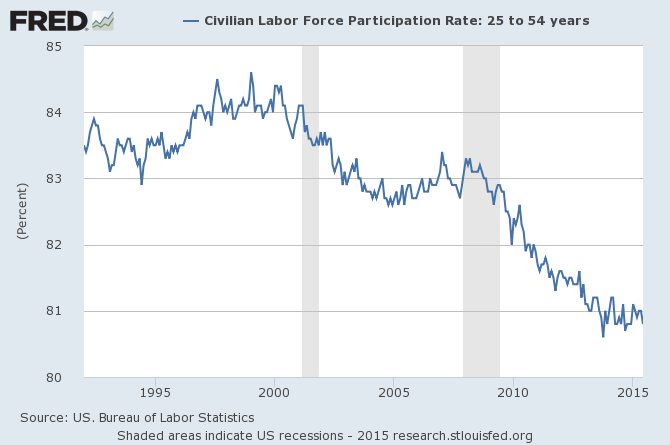

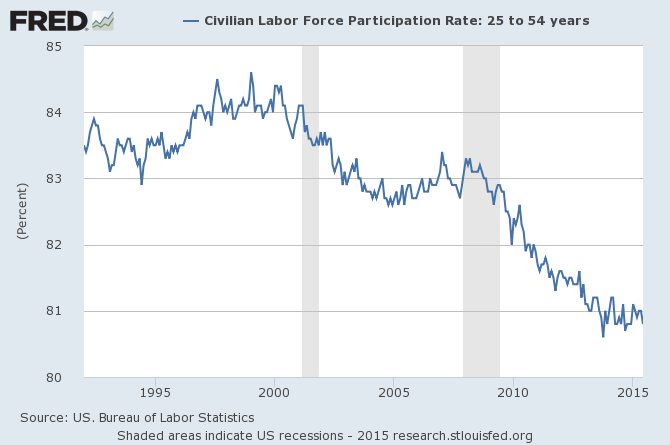

In her WaPo column Catherine Rampell points to the sharp decline in labor force participation rates for prime age workers (ages 25-54) in recent years and looks to the remedies proposed by Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton. Remarkably neither Rampell nor the candidates discuss the role of the Federal Reserve Board.

There is not much about the drop in labor force participation that is very surprising. It goes along with a weak labor market. When people can’t find a job after enough months or years of looking, they stop trying. Here’s what the picture looks like over the last two decades.

While the story would be somewhat different for men and women, we see that the labor force participation rate (LFPR) rose from the mid-1990s to the late 1990s during the strong labor market of those years. It fell with the 2001 recession and the weak recovery that followed. (We continued to lose jobs until late 2003 and didn’t get back the jobs lost in the downturn until early 2005.) After the labor market started to recover, the LFPR started to rise again, but then fell sharply with the downturn following the collapse of the housing bubble.

It’s great for politicians to round up their favorite usual suspects in trying to explain why so many prime age workers no longer feel like working, but to those not on the campaign payrolls, it seems pretty obvious. We don’t have enough demand in the economy and therefore we don’t have jobs.

This is where the Fed comes in. If the economy were to continue to create 200,000 plus jobs a month, then we can be pretty confident that the LFPR will rise again as it did in the late 1990s. However if the Fed is determined not to allow the unemployment rate to fall below some floor like 5.2 percent, then it will prevent the economy from creating large numbers of jobs. In this case, the LFPR will not rise much regardless of whether we follow the prescriptions of Bush or Clinton, since people will not look for jobs that are not there indefinitely.

It is worth noting in this respect that in the 1990s, the vast majority of economists, including Janet Yellen who was then a member of Fed’s Board of Governors, did not want the Fed to allow the unemployment rate to fall much below 6.0 percent. It was only because then Chair Alan Greenspan was not an orthodox economist that were able to see that the unemployment rate could in fact fall much lower without triggering inflation. (The unemployment rate averaged 4.0 percent in 2000.)

It should seem obvious that Fed’s policy will play a major role in determining the LFPR going forward. It is bizarre that it does not seem to be getting into the debate.

In her WaPo column Catherine Rampell points to the sharp decline in labor force participation rates for prime age workers (ages 25-54) in recent years and looks to the remedies proposed by Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton. Remarkably neither Rampell nor the candidates discuss the role of the Federal Reserve Board.

There is not much about the drop in labor force participation that is very surprising. It goes along with a weak labor market. When people can’t find a job after enough months or years of looking, they stop trying. Here’s what the picture looks like over the last two decades.

While the story would be somewhat different for men and women, we see that the labor force participation rate (LFPR) rose from the mid-1990s to the late 1990s during the strong labor market of those years. It fell with the 2001 recession and the weak recovery that followed. (We continued to lose jobs until late 2003 and didn’t get back the jobs lost in the downturn until early 2005.) After the labor market started to recover, the LFPR started to rise again, but then fell sharply with the downturn following the collapse of the housing bubble.

It’s great for politicians to round up their favorite usual suspects in trying to explain why so many prime age workers no longer feel like working, but to those not on the campaign payrolls, it seems pretty obvious. We don’t have enough demand in the economy and therefore we don’t have jobs.

This is where the Fed comes in. If the economy were to continue to create 200,000 plus jobs a month, then we can be pretty confident that the LFPR will rise again as it did in the late 1990s. However if the Fed is determined not to allow the unemployment rate to fall below some floor like 5.2 percent, then it will prevent the economy from creating large numbers of jobs. In this case, the LFPR will not rise much regardless of whether we follow the prescriptions of Bush or Clinton, since people will not look for jobs that are not there indefinitely.

It is worth noting in this respect that in the 1990s, the vast majority of economists, including Janet Yellen who was then a member of Fed’s Board of Governors, did not want the Fed to allow the unemployment rate to fall much below 6.0 percent. It was only because then Chair Alan Greenspan was not an orthodox economist that were able to see that the unemployment rate could in fact fall much lower without triggering inflation. (The unemployment rate averaged 4.0 percent in 2000.)

It should seem obvious that Fed’s policy will play a major role in determining the LFPR going forward. It is bizarre that it does not seem to be getting into the debate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Would a doctor work for Uber? Probably not, but if it turned out there were no jobs for doctors and the only way she could support her family was to work for Uber, then a doctor may work for Uber. That is an important point left out of an interesting article on growing economic insecurity for workers.

A big part of this story is the decision by the Federal Reserve Board to raise interest rates to deliberately limit the number of jobs in the economy. This disproportionately hits less educated workers, who are the first ones to be fired when the economy slows. If jobs were plentiful then employers would be forced to offer higher wages and more job security in order to attract the workers they need. The Fed’s policy to keep the labor market weak in the last three and a half decades has been a major factor in the deterioration of job quality.

It is also bizarre that the article cited a study by Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney to support the case that, controlling for education, men have been seeing declines in wages for forty years. The Economic Policy Institute had been documenting this decline in the State of Working America for decades.

Would a doctor work for Uber? Probably not, but if it turned out there were no jobs for doctors and the only way she could support her family was to work for Uber, then a doctor may work for Uber. That is an important point left out of an interesting article on growing economic insecurity for workers.

A big part of this story is the decision by the Federal Reserve Board to raise interest rates to deliberately limit the number of jobs in the economy. This disproportionately hits less educated workers, who are the first ones to be fired when the economy slows. If jobs were plentiful then employers would be forced to offer higher wages and more job security in order to attract the workers they need. The Fed’s policy to keep the labor market weak in the last three and a half decades has been a major factor in the deterioration of job quality.

It is also bizarre that the article cited a study by Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney to support the case that, controlling for education, men have been seeing declines in wages for forty years. The Economic Policy Institute had been documenting this decline in the State of Working America for decades.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s not quite how the paper put it, but it is in fact what it reported. The story according to the headline is “bipartisan partnership produces a health bill that passes house.” According to the article the bill instructs the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to use information from doctors’ practices and drug registries in determining whether to approve new drugs rather than just relying on clinical trials. The problem with this approach is that the industry often pays doctors to say good things about their drugs. It would difficult for the FDA to know for certain that the information it is relying upon was not paid for by the company seeking approval of a drug.

The piece also includes the interesting tidbit that the cost of additional funding for the FDA, another provision in the bill, would be covered by selling off some of the country’s petroleum reserve. This shows the remarkable cynicism of the deficit hawks in Congress.

Selling oil reserves is simply a shuffling of assets, it is not a way of either improving the government’s financial situation or reducing the drain on the economy from the budget deficit. It’s analogous to a household pawning its silverware to avoid having to borrow. There is no economic reason to prefer selling off this asset to adding debt, it is just a silly ritual that apparently is taken seriously in Washington policy circles these days.

That’s not quite how the paper put it, but it is in fact what it reported. The story according to the headline is “bipartisan partnership produces a health bill that passes house.” According to the article the bill instructs the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to use information from doctors’ practices and drug registries in determining whether to approve new drugs rather than just relying on clinical trials. The problem with this approach is that the industry often pays doctors to say good things about their drugs. It would difficult for the FDA to know for certain that the information it is relying upon was not paid for by the company seeking approval of a drug.

The piece also includes the interesting tidbit that the cost of additional funding for the FDA, another provision in the bill, would be covered by selling off some of the country’s petroleum reserve. This shows the remarkable cynicism of the deficit hawks in Congress.

Selling oil reserves is simply a shuffling of assets, it is not a way of either improving the government’s financial situation or reducing the drain on the economy from the budget deficit. It’s analogous to a household pawning its silverware to avoid having to borrow. There is no economic reason to prefer selling off this asset to adding debt, it is just a silly ritual that apparently is taken seriously in Washington policy circles these days.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what a NYT article seemed to be telling people. The center of the story is the fact that it appears that La Grange, Ill (population 15,550) was using grossly out of date mortality tables in calculating the pension obligations for its police and fire fighters. Without directly saying as much, the piece implies that this is a common problem with much larger pension funds and that such practices are the basis for the underfunding of many public sector pensions.

In fact, the main reason that some public sector funds face severe shortfalls is that politicians like Richard M. Daley and Chris Christie chose not to make required contributions. This is a serious problem since the country’s elites apparently praise such behavior. Since ending his last term as mayor of Chicago, Mr. Daley has been appointed a senior distinguished fellow at the University of Chicago, given a seat on the board of Coca Cola, and made a principal of the investment firm Tur Partners LLC. Chris Christie is running for the Republican presidential nomination. Reporters covering his campaign rarely mention his failure to make required pension contributions, including going back an explicit commitment to state employee unions, as a liability. If the people most directly responsible for the underfunding of pensions get rewarded, then it should not be surprising that we do have some cases of major underfunding.

Bizarrely, at one point the piece suggests that the public might look to actuaries as the main target for the underfunding of public sector pensions:

“Retirees are counting on the money promised to them. Taxpayers are in no mood to bail out troubled pension funds. Some are looking for scapegoats.

“‘Actuaries make a juicy target,’ said Mary Pat Campbell, an actuary who responded to the board’s call for comments.”

This is bizarre since Wall Street is the far more obvious target. The recession following the collapse of the housing bubble is likely to cost the country more than $10 trillion in lost output. This both directly contributed to pension shortfalls, by making it more difficult for governments to make required contributions to pensions during the recession years, and indirectly by reducing the revenue base of many governments on an ongoing basis. It is rather strange that taxpayers should look to target actuaries, most of whom make relatively modest salaries, rather than big Wall Street players who often make tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

That’s what a NYT article seemed to be telling people. The center of the story is the fact that it appears that La Grange, Ill (population 15,550) was using grossly out of date mortality tables in calculating the pension obligations for its police and fire fighters. Without directly saying as much, the piece implies that this is a common problem with much larger pension funds and that such practices are the basis for the underfunding of many public sector pensions.

In fact, the main reason that some public sector funds face severe shortfalls is that politicians like Richard M. Daley and Chris Christie chose not to make required contributions. This is a serious problem since the country’s elites apparently praise such behavior. Since ending his last term as mayor of Chicago, Mr. Daley has been appointed a senior distinguished fellow at the University of Chicago, given a seat on the board of Coca Cola, and made a principal of the investment firm Tur Partners LLC. Chris Christie is running for the Republican presidential nomination. Reporters covering his campaign rarely mention his failure to make required pension contributions, including going back an explicit commitment to state employee unions, as a liability. If the people most directly responsible for the underfunding of pensions get rewarded, then it should not be surprising that we do have some cases of major underfunding.

Bizarrely, at one point the piece suggests that the public might look to actuaries as the main target for the underfunding of public sector pensions:

“Retirees are counting on the money promised to them. Taxpayers are in no mood to bail out troubled pension funds. Some are looking for scapegoats.

“‘Actuaries make a juicy target,’ said Mary Pat Campbell, an actuary who responded to the board’s call for comments.”

This is bizarre since Wall Street is the far more obvious target. The recession following the collapse of the housing bubble is likely to cost the country more than $10 trillion in lost output. This both directly contributed to pension shortfalls, by making it more difficult for governments to make required contributions to pensions during the recession years, and indirectly by reducing the revenue base of many governments on an ongoing basis. It is rather strange that taxpayers should look to target actuaries, most of whom make relatively modest salaries, rather than big Wall Street players who often make tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Thomas Edsall had a very good piece on divisions in the Democratic Party over trade policy in the NYT this morning. The piece cites a large body of academic research pointing out that U.S. trade policy has played a large role in destroying manufacturing jobs and redistributing income upwards. It notes that this is the basis of the opposition of unions to trade policy, which has caused the overwhelming majority of Democrats in Congress to oppose the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

However the piece errors in referring to the TPP and U.S. trade policy in general as “free trade.” It is absolutely not free trade.

One of the main goals of the TPP is to increase patent and copyright protection. That is protection as in protectionism. These government granted monopolies can increase the price of drugs and other protected items by several thousand percent. This has the same economic impact and leads to the same distortions as tariffs of several thousand percent. Markets do not care if the price of a product is raised due to a tariff or a government granted patent monopoly, it leads to the same distortions.

These trade deals have also done almost nothing to remove the protectionist barriers that make it difficult for foreigners to train to become doctors, dentists, or other professionals and work in the United States. The reasons that these highly paid professions have not seen their salaries hurt by trade is due to the fact that the government has protected them, not that there is some inherent impossibility in Indians training to U.S. standards and becoming doctors in the United States.

Also, a free trade policy would mean pushing for freely floating currencies. This has clearly not been a priority for the Obama administration as our trading partners, most importantly China, have accumulated trillions of dollars of foreign reserves in order to inflate the value of the dollar against their currencies, thereby supporting their large trade surpluses. The Obama administration chose to not even include currency as a topic in the TPP.

It is important to point out that our trade policy is not free trade first because it might lead some to believe that our trade policy involves pursuing some great economic principle. It doesn’t. It’s about redistributing money to the rich.

Second, it is important because at this point the biggest gains for “everyday people” will actually come from more free trade, not less. It’s not realistic to think that the United States will erect tariffs or other barriers that will block the import of manufactured goods from Mexico, China, and other developing countries. It is reasonably to think that we might push for more market based exchange rates, less costly patent and copyright protection, and the elimination of unnecessary professional restrictions that prevent us from having lower cost health care, legal services, and other professional services.

Thomas Edsall had a very good piece on divisions in the Democratic Party over trade policy in the NYT this morning. The piece cites a large body of academic research pointing out that U.S. trade policy has played a large role in destroying manufacturing jobs and redistributing income upwards. It notes that this is the basis of the opposition of unions to trade policy, which has caused the overwhelming majority of Democrats in Congress to oppose the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

However the piece errors in referring to the TPP and U.S. trade policy in general as “free trade.” It is absolutely not free trade.

One of the main goals of the TPP is to increase patent and copyright protection. That is protection as in protectionism. These government granted monopolies can increase the price of drugs and other protected items by several thousand percent. This has the same economic impact and leads to the same distortions as tariffs of several thousand percent. Markets do not care if the price of a product is raised due to a tariff or a government granted patent monopoly, it leads to the same distortions.

These trade deals have also done almost nothing to remove the protectionist barriers that make it difficult for foreigners to train to become doctors, dentists, or other professionals and work in the United States. The reasons that these highly paid professions have not seen their salaries hurt by trade is due to the fact that the government has protected them, not that there is some inherent impossibility in Indians training to U.S. standards and becoming doctors in the United States.

Also, a free trade policy would mean pushing for freely floating currencies. This has clearly not been a priority for the Obama administration as our trading partners, most importantly China, have accumulated trillions of dollars of foreign reserves in order to inflate the value of the dollar against their currencies, thereby supporting their large trade surpluses. The Obama administration chose to not even include currency as a topic in the TPP.

It is important to point out that our trade policy is not free trade first because it might lead some to believe that our trade policy involves pursuing some great economic principle. It doesn’t. It’s about redistributing money to the rich.

Second, it is important because at this point the biggest gains for “everyday people” will actually come from more free trade, not less. It’s not realistic to think that the United States will erect tariffs or other barriers that will block the import of manufactured goods from Mexico, China, and other developing countries. It is reasonably to think that we might push for more market based exchange rates, less costly patent and copyright protection, and the elimination of unnecessary professional restrictions that prevent us from having lower cost health care, legal services, and other professional services.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The media seem to think it’s a really huge deal that investors in China’s stock market have not made any money since February. The Washington Post told readers that it could even threaten the regime’s legitimacy in a front page story headlined, “stock slide sandbags China’s leaders.”

The article begins:

“For decades, the Chinese Communist Party has been able to keep control of democracy protests, dissidents, the legal system and the military, but it is now facing an even more intractable foe: a plummeting stock market.

“Invisible and fast-paced, mutinous market forces have defied the party-led government’s efforts to arrest the month-long slide in Chinese stock markets. If this continues, the slump in stock prices could slow the economy and undermine faith in the party’s leadership and power, experts on China and economics say.”

This is an interesting assessment. Those of us who are less expert on China than experts consulted for this article might wonder how the regime managed to survive a stock market crash between October of 2007 and October of 2008 in which the market lost over 60 percent of its value. This is more than twice as large a decline as the market has experienced in the current downturn. In spite of this plunge, China’s economy grew more than 9.0 percent in 2009, although it did require a substantial government stimulus program.

The piece also contains the strange paragraph:

“For decades, some enthusiasts have argued that China was the exception to the rule: that its farsighted leaders could make the transition to a more open economy while avoiding the debt trap that every other so-called miracle economy had fallen into since World War II. That idea could be the biggest casualty of the crash, both at home and abroad.”

It’s not clear what the article means in asserting that every other miracle economy has fallen into a debt trap. South Korea and Taiwan have experienced rapid and sustained growth for more than five decades, with only brief periods of recessions. As a result, South Korea now has a per capita income that is roughly 90 percent of the per capita income in the United Kingdom. Taiwan’s income is more than 15 percent higher. Are these countries not supposed to be “so-called miracle economies” or is this the record of economies mired in a “debt-trap?”

Addendum:

China’s stock market rose 5.8 percent today.

The media seem to think it’s a really huge deal that investors in China’s stock market have not made any money since February. The Washington Post told readers that it could even threaten the regime’s legitimacy in a front page story headlined, “stock slide sandbags China’s leaders.”

The article begins:

“For decades, the Chinese Communist Party has been able to keep control of democracy protests, dissidents, the legal system and the military, but it is now facing an even more intractable foe: a plummeting stock market.

“Invisible and fast-paced, mutinous market forces have defied the party-led government’s efforts to arrest the month-long slide in Chinese stock markets. If this continues, the slump in stock prices could slow the economy and undermine faith in the party’s leadership and power, experts on China and economics say.”

This is an interesting assessment. Those of us who are less expert on China than experts consulted for this article might wonder how the regime managed to survive a stock market crash between October of 2007 and October of 2008 in which the market lost over 60 percent of its value. This is more than twice as large a decline as the market has experienced in the current downturn. In spite of this plunge, China’s economy grew more than 9.0 percent in 2009, although it did require a substantial government stimulus program.

The piece also contains the strange paragraph:

“For decades, some enthusiasts have argued that China was the exception to the rule: that its farsighted leaders could make the transition to a more open economy while avoiding the debt trap that every other so-called miracle economy had fallen into since World War II. That idea could be the biggest casualty of the crash, both at home and abroad.”

It’s not clear what the article means in asserting that every other miracle economy has fallen into a debt trap. South Korea and Taiwan have experienced rapid and sustained growth for more than five decades, with only brief periods of recessions. As a result, South Korea now has a per capita income that is roughly 90 percent of the per capita income in the United Kingdom. Taiwan’s income is more than 15 percent higher. Are these countries not supposed to be “so-called miracle economies” or is this the record of economies mired in a “debt-trap?”

Addendum:

China’s stock market rose 5.8 percent today.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión