Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is remarkable how many people seem unfamiliar with the idea of productivity growth. It’s a fairly simple concept. It means that workers can produce more output in each hour of work. The world economy has been seeing consistent productivity growth for more than two hundred years. That is why we have seen rising living standards. We live longer and better than our ancestors.

When we hear people running around saying that the robots will take all the jobs, that is a story of productivity growth. The argument is that each worker would be able to produce much more in a day’s work because she is working alongside super-productive robots. If these folks had heard of productivity growth then they would know the key question is the rate of productivity growth and whether there is any reason to believe that it will be faster in the future than what we have seen in the past, and furthermore even if faster, whether it will be so much faster as to lead to mass unemployment.

The answer is certainly “no.” Productivity growth has been slow in recent years and would have to accelerate enormously to reach the 3.0 percent pace of the Golden Age from 1947-73. And, that was a period of low unemployment and rising wages. There is a story of high unemployment and stagnant wages, but that is a story of bad Fed policy, bad currency policy, and bad fiscal policy. It is not the robots’ fault.

Yesterday the Post gave us the opposite picture in a piece from Max Fisher which warned of China’s demographic crisis because it faces slowing and then declining population growth. The argument is that it won’t have enough workers to take care of its aging population. This one is really bizarre since China has been experiencing rapid productivity and rapid wage growth, which means that even if fewer workers are supporting each retiree, both workers and retirees can still enjoy sharply rising living standards.

This can be easily seen with some simple arithmetic. Suppose they go from having five workers to each retiree to just two over a twenty year period. This is a far sharper decline than China will actually see. Now suppose their rate of productivity and real wage growth is 5.0 percent annually, much slower than they actually have seen. And, assume that a retiree needs 80 percent of the income of an average worker.

In the first year, a worker would have to pay a bit less than 14 percent of their wages in taxes to support the retired population. If we base their before their tax wage as 100, this leaves them with an after-tax wage of 86. By year twenty the tax rate would need to be almost 29 percent in order for two workers to provide an income that is equal to 80 percent of the workers’ after-tax income. Sound scary, right?

Well, the wage in year 20 will be 165 percent higher than it was in year one. This means that the after-tax wage will be almost 190 on our index, or more than twice what it had been twenty years earlier. And our retiree will also have more than twice as much income as they had twenty years earlier. Where’s the crisis?

Furthermore, this is a low point. Once we reach our ratio of two workers per retiree there is little change going forward. The country does not keep getting older, or at least it does so at a very slow pace. But productivity continues to grow. If we go thirty years out from our start point then the wages of workers the index for after tax wages would be over 300 in the 5.0 percent productivity growth story, more than three times the initial level. Even with 2.0 productivity growth after year 20 the index for after-tax wages would be at 230, almost 170 percent higher than the wage workers had received thirty years earlier.

As a practical matter, the reduced supply of labor just means the least productive jobs go unfilled. No one works the midnight shift at convenience stores. And, it is harder to find people to mow your lawn or clean your house for low pay. Life is tough.

Addendum

This is apparently a two year old piece. I have no idea why the Post decided to feature it today.

It is remarkable how many people seem unfamiliar with the idea of productivity growth. It’s a fairly simple concept. It means that workers can produce more output in each hour of work. The world economy has been seeing consistent productivity growth for more than two hundred years. That is why we have seen rising living standards. We live longer and better than our ancestors.

When we hear people running around saying that the robots will take all the jobs, that is a story of productivity growth. The argument is that each worker would be able to produce much more in a day’s work because she is working alongside super-productive robots. If these folks had heard of productivity growth then they would know the key question is the rate of productivity growth and whether there is any reason to believe that it will be faster in the future than what we have seen in the past, and furthermore even if faster, whether it will be so much faster as to lead to mass unemployment.

The answer is certainly “no.” Productivity growth has been slow in recent years and would have to accelerate enormously to reach the 3.0 percent pace of the Golden Age from 1947-73. And, that was a period of low unemployment and rising wages. There is a story of high unemployment and stagnant wages, but that is a story of bad Fed policy, bad currency policy, and bad fiscal policy. It is not the robots’ fault.

Yesterday the Post gave us the opposite picture in a piece from Max Fisher which warned of China’s demographic crisis because it faces slowing and then declining population growth. The argument is that it won’t have enough workers to take care of its aging population. This one is really bizarre since China has been experiencing rapid productivity and rapid wage growth, which means that even if fewer workers are supporting each retiree, both workers and retirees can still enjoy sharply rising living standards.

This can be easily seen with some simple arithmetic. Suppose they go from having five workers to each retiree to just two over a twenty year period. This is a far sharper decline than China will actually see. Now suppose their rate of productivity and real wage growth is 5.0 percent annually, much slower than they actually have seen. And, assume that a retiree needs 80 percent of the income of an average worker.

In the first year, a worker would have to pay a bit less than 14 percent of their wages in taxes to support the retired population. If we base their before their tax wage as 100, this leaves them with an after-tax wage of 86. By year twenty the tax rate would need to be almost 29 percent in order for two workers to provide an income that is equal to 80 percent of the workers’ after-tax income. Sound scary, right?

Well, the wage in year 20 will be 165 percent higher than it was in year one. This means that the after-tax wage will be almost 190 on our index, or more than twice what it had been twenty years earlier. And our retiree will also have more than twice as much income as they had twenty years earlier. Where’s the crisis?

Furthermore, this is a low point. Once we reach our ratio of two workers per retiree there is little change going forward. The country does not keep getting older, or at least it does so at a very slow pace. But productivity continues to grow. If we go thirty years out from our start point then the wages of workers the index for after tax wages would be over 300 in the 5.0 percent productivity growth story, more than three times the initial level. Even with 2.0 productivity growth after year 20 the index for after-tax wages would be at 230, almost 170 percent higher than the wage workers had received thirty years earlier.

As a practical matter, the reduced supply of labor just means the least productive jobs go unfilled. No one works the midnight shift at convenience stores. And, it is harder to find people to mow your lawn or clean your house for low pay. Life is tough.

Addendum

This is apparently a two year old piece. I have no idea why the Post decided to feature it today.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The gods must have a great a sense of humor. Why else would they arrange to have the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank both come up as great national issues at the same time?

If anyone is missing the irony, the TPP is being sold as “free trade.” This is a great holy principle enshrined in intro econ textbooks everywhere. Since the TPP is called a “free-trade” agreement, those who opposed to it are ignorant Neanderthals who should not be taken seriously.

However the Export-Import Bank is about subsidies for U.S. exports. It is 180 degrees at odds with free trade. It means the government is effectively taxing the rest of us to give money to favored corporations, primarily folks like Boeing, GE, Caterpillar Tractor and a small number of other huge corporations.[1]

The great part of the picture is that most of the strongest proponents of the TPP are also big supporters of the Export-Import Bank. They apparently have zero problem touting the virtues of free trade while at the same time pushing an institution that primarily exists to subsidize exports. Isn’t American politics just the best?

[1] The supporters of the Export-Import Bank insist that the bank makes a profit and therefore does not involve a subsidy from taxpayers. This is bit of fancy footwork designed to deceive the naïve. By taking advantage of the government’s ability to borrow at extremely low interest rates, the bank can still make money on the difference between the subsidized loan rate provided to its clients and the government’s own borrowing rate. However, in standard economic models that assume full employment (the ones you need to get the story that free trade is good) the bank’s subsidized loans are raising the cost of capital for everyone else by diverting capital to the favored corporations. For this reason the subsidized loans are still effectively imposing a tax on the rest of us, the accounting system just provides an effective way to hide this fact.

The gods must have a great a sense of humor. Why else would they arrange to have the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank both come up as great national issues at the same time?

If anyone is missing the irony, the TPP is being sold as “free trade.” This is a great holy principle enshrined in intro econ textbooks everywhere. Since the TPP is called a “free-trade” agreement, those who opposed to it are ignorant Neanderthals who should not be taken seriously.

However the Export-Import Bank is about subsidies for U.S. exports. It is 180 degrees at odds with free trade. It means the government is effectively taxing the rest of us to give money to favored corporations, primarily folks like Boeing, GE, Caterpillar Tractor and a small number of other huge corporations.[1]

The great part of the picture is that most of the strongest proponents of the TPP are also big supporters of the Export-Import Bank. They apparently have zero problem touting the virtues of free trade while at the same time pushing an institution that primarily exists to subsidize exports. Isn’t American politics just the best?

[1] The supporters of the Export-Import Bank insist that the bank makes a profit and therefore does not involve a subsidy from taxpayers. This is bit of fancy footwork designed to deceive the naïve. By taking advantage of the government’s ability to borrow at extremely low interest rates, the bank can still make money on the difference between the subsidized loan rate provided to its clients and the government’s own borrowing rate. However, in standard economic models that assume full employment (the ones you need to get the story that free trade is good) the bank’s subsidized loans are raising the cost of capital for everyone else by diverting capital to the favored corporations. For this reason the subsidized loans are still effectively imposing a tax on the rest of us, the accounting system just provides an effective way to hide this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a Washington Post column today, Delaware Governor Jack Markell and Third Way President Jonathan Cowan took a swipe at the progressive wing of the Democratic Party in arguing for a set of ill-defined centrist proposals. (For example, they want better schools — great idea.) There is much about their piece that is wrong or misleading (they imply that the rebuilding of Europe and Japan impedes growth and makes us poorer, that’s not what standard trade theory says), but the best part is in the last paragraph where they tell readers:

“Nine years ago, Borders Books had more than 1,000 stores and more than 35,000 employees. Four years ago, it liquidated. Those stores didn’t close and those employees didn’t lose their jobs because the economic system was rigged against ordinary Americans. They closed because technology brought us Amazon and the Kindle.”

Actually, Border Books did close in large part because the economic system is rigged against ordinary Americans. One of the main reasons Amazon has been able to grow as rapidly as it did is that Amazon has not been required to collect the same sales tax as its brick and mortar competitors in most states for most of its existence. The savings on sales tax almost certainly exceeded its cumulative profits since it was founded in 1994.

While there is no policy rationale to exempt businesses from the obligation to collect sales tax because they are Internet based, this exemption has allowed Amazon to become a huge company and made its founder, Jeff Bezos one of the richest people in the world. Oh yeah, Jeff Bezos now owns the Washington Post.

Addendum

I see many folks have a hard time believing that sales tax mattered to Amazon’s growth. While readers here may exclusively buy books in stores or on the web. Many do both. And for most of these people it is very likely that if they had to pay 5-8 percent more for the books purchased on the web that they would have bought more in stores. If would add, that if didn’t matter to these people, then we have to wonder why Amazon and other Internet retailers didn’t just raise their prices by 5-8 percent and put more money in their pockets?

Again, the amount at stake here is almost certainly more than Amazon’s cumulative profits. That makes it a big deal.

In a Washington Post column today, Delaware Governor Jack Markell and Third Way President Jonathan Cowan took a swipe at the progressive wing of the Democratic Party in arguing for a set of ill-defined centrist proposals. (For example, they want better schools — great idea.) There is much about their piece that is wrong or misleading (they imply that the rebuilding of Europe and Japan impedes growth and makes us poorer, that’s not what standard trade theory says), but the best part is in the last paragraph where they tell readers:

“Nine years ago, Borders Books had more than 1,000 stores and more than 35,000 employees. Four years ago, it liquidated. Those stores didn’t close and those employees didn’t lose their jobs because the economic system was rigged against ordinary Americans. They closed because technology brought us Amazon and the Kindle.”

Actually, Border Books did close in large part because the economic system is rigged against ordinary Americans. One of the main reasons Amazon has been able to grow as rapidly as it did is that Amazon has not been required to collect the same sales tax as its brick and mortar competitors in most states for most of its existence. The savings on sales tax almost certainly exceeded its cumulative profits since it was founded in 1994.

While there is no policy rationale to exempt businesses from the obligation to collect sales tax because they are Internet based, this exemption has allowed Amazon to become a huge company and made its founder, Jeff Bezos one of the richest people in the world. Oh yeah, Jeff Bezos now owns the Washington Post.

Addendum

I see many folks have a hard time believing that sales tax mattered to Amazon’s growth. While readers here may exclusively buy books in stores or on the web. Many do both. And for most of these people it is very likely that if they had to pay 5-8 percent more for the books purchased on the web that they would have bought more in stores. If would add, that if didn’t matter to these people, then we have to wonder why Amazon and other Internet retailers didn’t just raise their prices by 5-8 percent and put more money in their pockets?

Again, the amount at stake here is almost certainly more than Amazon’s cumulative profits. That makes it a big deal.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Frank Bruni has a very good column on the pay packages of presidents at universities around the country. Bruni points out that many make well over a million dollars a year and some of them make several million a year, when their pension is included.

One aspect to this issue that Bruni neglects to mention is that these pay packages come largely at the public’s expense. In the case of public universities, the school are largely financed with public funds, so the taxpayer involvement is quite direct. However even at a private university like Yale, which Bruni reports gave an $8.5 million going away president to its retiring president Richard Levin, the taxpayers subsidize the cost through its tax exempt status. Insofar as money is given to Yale from high income earners, the tax deduction means that the government is losing more than 40 cents on the dollar.

Clearly there is a failure of governance at these institutions where the boards that control them have little incentive to restrain pay at the top. This is likely the case because there are often personal ties between the boards and the presidents and hey, why wouldn’t they want to give someone else’s money to their friends?

It is striking that pay of these university presidents is not more of an issue at a time when there has been a great effort to highlight the pay and especially the pensions of public sector employees. The deferred pay given to Yale’s former president would be equal to roughly 500 pension years for the retired Detroit municipal employees.

The pay of university presidents should also be an issue in plans to make college free or at least less expensive. If college is to be affordable to students or the public, if taxpayers end up footing the bill, then it will be difficult to support such outlandish pay packages for those at the top. The excessive pay for college presidents does not only directly imply substantial costs, it leads to inflated pay for other top university administrators.

The president of the United States gets $400,000 a year. That seems a reasonable limit for public universities or private ones that benefit from tax exempt status. If a school can’t attract good help for this pay, it is probably not the sort of institution that deserves the public’s support.

Frank Bruni has a very good column on the pay packages of presidents at universities around the country. Bruni points out that many make well over a million dollars a year and some of them make several million a year, when their pension is included.

One aspect to this issue that Bruni neglects to mention is that these pay packages come largely at the public’s expense. In the case of public universities, the school are largely financed with public funds, so the taxpayer involvement is quite direct. However even at a private university like Yale, which Bruni reports gave an $8.5 million going away president to its retiring president Richard Levin, the taxpayers subsidize the cost through its tax exempt status. Insofar as money is given to Yale from high income earners, the tax deduction means that the government is losing more than 40 cents on the dollar.

Clearly there is a failure of governance at these institutions where the boards that control them have little incentive to restrain pay at the top. This is likely the case because there are often personal ties between the boards and the presidents and hey, why wouldn’t they want to give someone else’s money to their friends?

It is striking that pay of these university presidents is not more of an issue at a time when there has been a great effort to highlight the pay and especially the pensions of public sector employees. The deferred pay given to Yale’s former president would be equal to roughly 500 pension years for the retired Detroit municipal employees.

The pay of university presidents should also be an issue in plans to make college free or at least less expensive. If college is to be affordable to students or the public, if taxpayers end up footing the bill, then it will be difficult to support such outlandish pay packages for those at the top. The excessive pay for college presidents does not only directly imply substantial costs, it leads to inflated pay for other top university administrators.

The president of the United States gets $400,000 a year. That seems a reasonable limit for public universities or private ones that benefit from tax exempt status. If a school can’t attract good help for this pay, it is probably not the sort of institution that deserves the public’s support.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus is unhappy with Senator Elizabeth Warren’s opposition to the trade agreement. In particular Marcus is upset that Senator Warren has complained that the deal is secret, calling this a bogus argument. I won’t go through the whole piece (this stuff has been addressed many places), but I do want to deal with one point Marcus raises.

She noted that Warren pointed out that President Bush had made the draft text of the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement public, but then tells readers:

“the countries involved in the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreed to make initial proposals public.”

This gets us to the Incredible Hulk theory of international relations. For those not familiar with comic book story or movie, the Incredible Hulk is the huge green monster that mild mannered physicist Bruce Banner turns into when he gets angry. This captures Marcus’ theory of international relations.

When the United States really wants something, for example if it wants European countries to crack down on bank accounts that might be used to launder money for Al Qaeda, the administration makes demands and gets them met. This is the Incredible Hulk part of the story. But then we get a situation where President Obama would really like to make the draft text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership available to the public, but our negotiating partners just won’t let us. This is the story of mild-mannered physicist Bruce Banner.

So the question everyone should ask themselves is, “do we think that if President Obama called our negotiating partners in the TPP and said that he really wants to make a draft public (it will be public soon anyhow), that all or any of them would refuse?”

My answer to this question is “no,” but if you want to believe otherwise, I have lots of comic books for you.

Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus is unhappy with Senator Elizabeth Warren’s opposition to the trade agreement. In particular Marcus is upset that Senator Warren has complained that the deal is secret, calling this a bogus argument. I won’t go through the whole piece (this stuff has been addressed many places), but I do want to deal with one point Marcus raises.

She noted that Warren pointed out that President Bush had made the draft text of the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement public, but then tells readers:

“the countries involved in the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreed to make initial proposals public.”

This gets us to the Incredible Hulk theory of international relations. For those not familiar with comic book story or movie, the Incredible Hulk is the huge green monster that mild mannered physicist Bruce Banner turns into when he gets angry. This captures Marcus’ theory of international relations.

When the United States really wants something, for example if it wants European countries to crack down on bank accounts that might be used to launder money for Al Qaeda, the administration makes demands and gets them met. This is the Incredible Hulk part of the story. But then we get a situation where President Obama would really like to make the draft text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership available to the public, but our negotiating partners just won’t let us. This is the story of mild-mannered physicist Bruce Banner.

So the question everyone should ask themselves is, “do we think that if President Obama called our negotiating partners in the TPP and said that he really wants to make a draft public (it will be public soon anyhow), that all or any of them would refuse?”

My answer to this question is “no,” but if you want to believe otherwise, I have lots of comic books for you.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

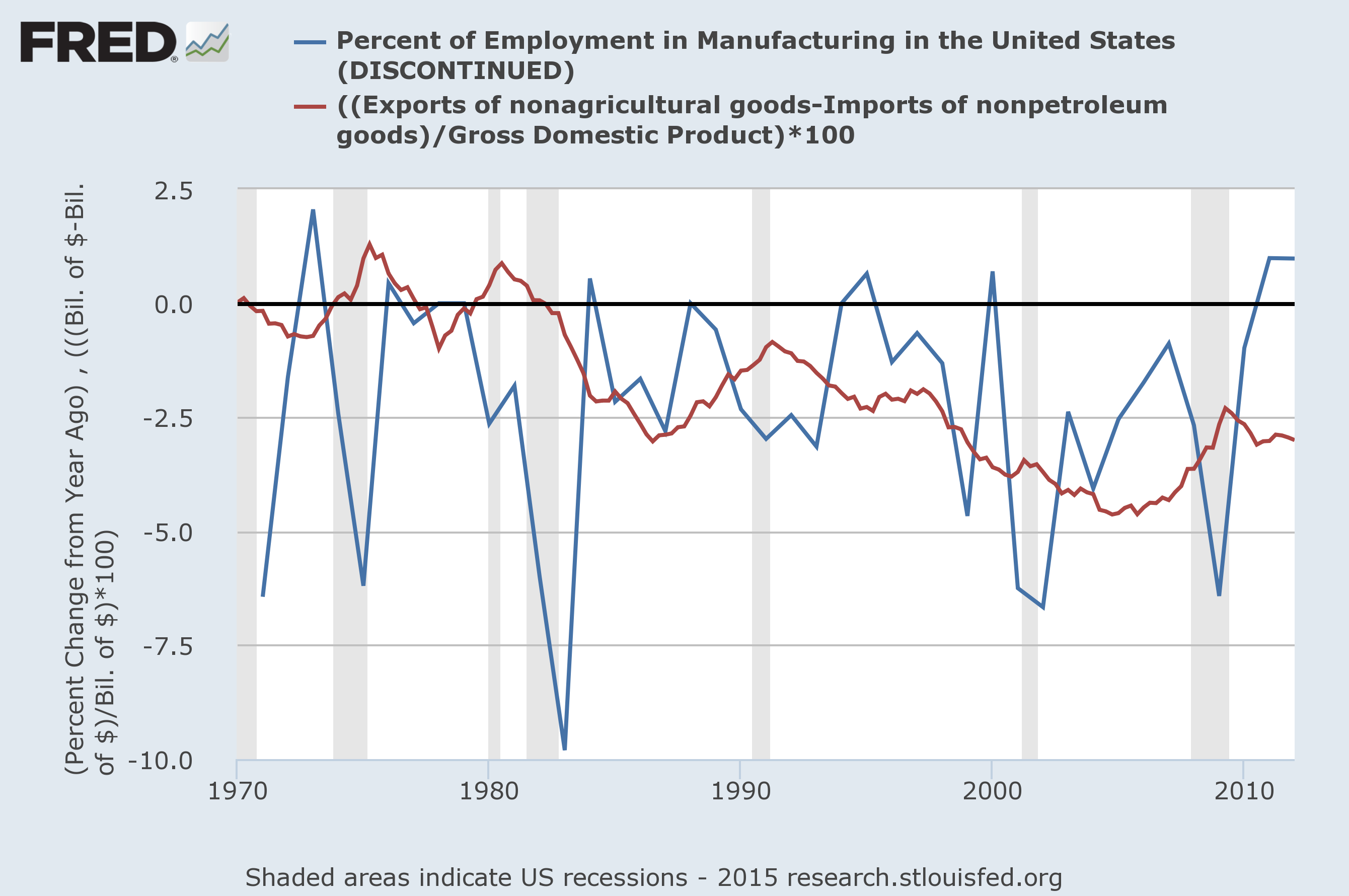

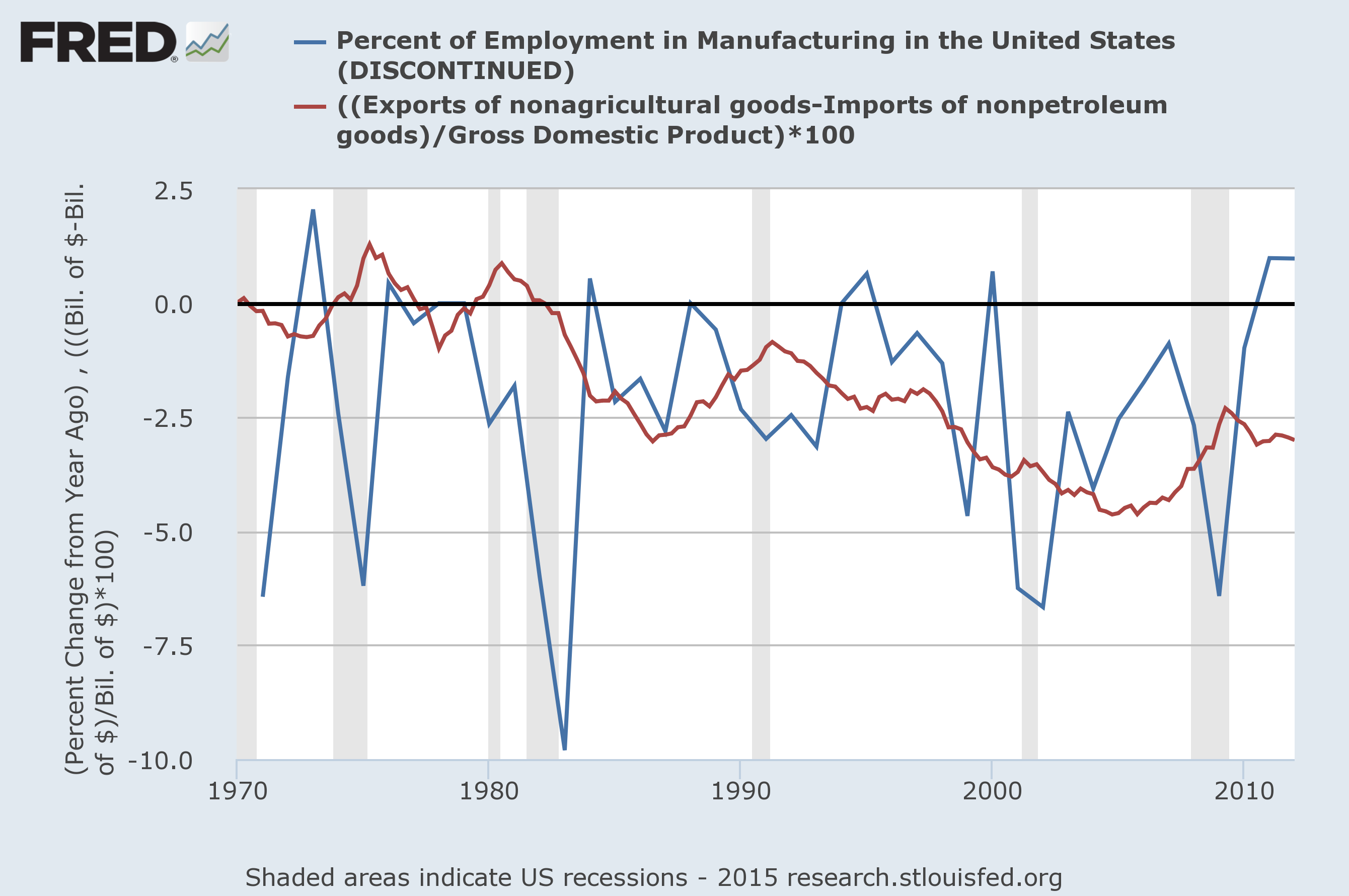

Paul Krugman addressed the question of whether the decline in manufacturing employment can be attributed to the trade deficit. He rightly points out that most of the decline is due to productivity growth, but notes the trade deficit has been a contributing factor. It is worth adding a bit more to the discussion.

The manufacturing share of employment has been declining for more than half a century. The story is that productivity growth is generally faster in manufacturing than the rest of the economy. If, as a first approximation, our demand for manufactured goods increases at the same pace as our demand for all goods and services, then this means we will see a declining share of employment in manufacturing over time.

However, a trade deficit adds to this loss by having a substantial share of manufactured output produced elsewhere. This means that in addition to needing fewer workers to produce the manufactured goods we consume as a result of productivity growth, we also need fewer workers in the United States since a portion of our manufactured goods are being provided by workers in other countries.

This not very pretty graph shows the percent change in the share of manufacturing employment compared to the non-oil, non-agricultural deficit in goods trade as a share of GDP. Note the sharp in decline in shares in the 2000s when the trade deficit was increasing rapidly. In 1997, when the trade deficit in goods was 2.0 percent of GDP, manufacturing accounted for 17.2 percent of total employment. When the deficit peaks at 4.6 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2005, manufacturing employment was down to 11.5 percent of total employment. This is a decline in share of almost one-third in the span of just eight years. That was not due to productivity growth.

It is incredibly dishonest for proponents of TPP to try to pretend that imports don’t displace manufacturing jobs. They do. This doesn’t necessarily mean that TPP is a bad pact, it is just one of the factors that has to be considered in assessing the deal. If the TPP proponents don’t think they can acknowledge this simple fact and still sell their trade pact, then they must not think they have cut a very good deal for the country.

Paul Krugman addressed the question of whether the decline in manufacturing employment can be attributed to the trade deficit. He rightly points out that most of the decline is due to productivity growth, but notes the trade deficit has been a contributing factor. It is worth adding a bit more to the discussion.

The manufacturing share of employment has been declining for more than half a century. The story is that productivity growth is generally faster in manufacturing than the rest of the economy. If, as a first approximation, our demand for manufactured goods increases at the same pace as our demand for all goods and services, then this means we will see a declining share of employment in manufacturing over time.

However, a trade deficit adds to this loss by having a substantial share of manufactured output produced elsewhere. This means that in addition to needing fewer workers to produce the manufactured goods we consume as a result of productivity growth, we also need fewer workers in the United States since a portion of our manufactured goods are being provided by workers in other countries.

This not very pretty graph shows the percent change in the share of manufacturing employment compared to the non-oil, non-agricultural deficit in goods trade as a share of GDP. Note the sharp in decline in shares in the 2000s when the trade deficit was increasing rapidly. In 1997, when the trade deficit in goods was 2.0 percent of GDP, manufacturing accounted for 17.2 percent of total employment. When the deficit peaks at 4.6 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2005, manufacturing employment was down to 11.5 percent of total employment. This is a decline in share of almost one-third in the span of just eight years. That was not due to productivity growth.

It is incredibly dishonest for proponents of TPP to try to pretend that imports don’t displace manufacturing jobs. They do. This doesn’t necessarily mean that TPP is a bad pact, it is just one of the factors that has to be considered in assessing the deal. If the TPP proponents don’t think they can acknowledge this simple fact and still sell their trade pact, then they must not think they have cut a very good deal for the country.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión