In the United States it’s considered fine to just make crap up when talking about the government, especially when it comes to programs for poor people. That is why Ronald Reagan ran around the country telling people about the welfare queen who drove up to the welfare office every month in her new Cadillac to pick up her check.

Today, David Brooks does the welfare queen routine in his NYT column, telling readers:

“Since 1980 federal antipoverty spending has exploded. As Robert Samuelson of The Washington Post has pointed out, in 2013 the federal government spent nearly $14,000 per poor person. If you simply took that money and handed it to the poor, a family of four would have a household income roughly twice the poverty rate.”

Of course if NYT columnists were expected to be accurate when they talked about government programs, Brooks would have been forced to tell readers that around 40 percent of these payments are Medicaid payments that go directly to doctors and other health care providers. We pay twice as much per person for our health care as people in other wealthy countries, with little to show in the way of outcomes. We can think of these high health care costs as a generous payment to the poor, but what this actually means is that every time David Brooks’ cardiologist neighbor raises his fees, David Brooks will complain about how we are being too generous to the poor.

The other point that an honest columnist would be forced to make is that the vast majority of these payments do not go to people who are below the poverty line and therefore don’t count in the denominator for his “poor person” calculation. The cutoff for Medicaid is well above the poverty level in most states. The same is true for food stamps, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and most of the other programs that make up Brooks’ $14,000 per person figure. In other words, he has taken the spending that goes to a much larger population and divided it by the number of people who are classified as poor.

If Brooks actually wants to tell readers what we spend on poor people, it’s not hard to find the data. The average family of three on TANF gets less than $500 a month. The average food stamp benefit is $133 per person. If low income people are working, they can get around $5,000 a year from the EITC for a single person with two children at the poverty level. (They would get less at lower income levels.)

These programs account for the vast majority of federal government payments to poor people. It won’t get you anywhere near David Brooks’ $14,000 per person per year, but why spoil a good story with facts?

Addendum:

Folks seem anxious to count Medicaid spending as spending on the poor. That’s fine by me. The point I was making is that we pay twice as much as people elsewhere in the world for care that is no better because doctors and other providers get paid twice as much.

That seems worth noting in an assessment of how generous we are to the poor. To take an overblown analogy, suppose terrorists took some number of poor people hostage and demanded tens of millions of dollars for their release. We can include our ransom payments as money spent on the poor and say again how generous we are.

In this case, the folks playing the role of the terrorists in making big money demands are the doctors and other health care providers. In other words, they are David Brooks’ cardiologist neighbor who gets well over $400,000 a year in large part due to payments from the government. You’re welcome to see this as generosity to the poor, I see it as generosity to David Brooks’ cardiologist neighbor.

In the United States it’s considered fine to just make crap up when talking about the government, especially when it comes to programs for poor people. That is why Ronald Reagan ran around the country telling people about the welfare queen who drove up to the welfare office every month in her new Cadillac to pick up her check.

Today, David Brooks does the welfare queen routine in his NYT column, telling readers:

“Since 1980 federal antipoverty spending has exploded. As Robert Samuelson of The Washington Post has pointed out, in 2013 the federal government spent nearly $14,000 per poor person. If you simply took that money and handed it to the poor, a family of four would have a household income roughly twice the poverty rate.”

Of course if NYT columnists were expected to be accurate when they talked about government programs, Brooks would have been forced to tell readers that around 40 percent of these payments are Medicaid payments that go directly to doctors and other health care providers. We pay twice as much per person for our health care as people in other wealthy countries, with little to show in the way of outcomes. We can think of these high health care costs as a generous payment to the poor, but what this actually means is that every time David Brooks’ cardiologist neighbor raises his fees, David Brooks will complain about how we are being too generous to the poor.

The other point that an honest columnist would be forced to make is that the vast majority of these payments do not go to people who are below the poverty line and therefore don’t count in the denominator for his “poor person” calculation. The cutoff for Medicaid is well above the poverty level in most states. The same is true for food stamps, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and most of the other programs that make up Brooks’ $14,000 per person figure. In other words, he has taken the spending that goes to a much larger population and divided it by the number of people who are classified as poor.

If Brooks actually wants to tell readers what we spend on poor people, it’s not hard to find the data. The average family of three on TANF gets less than $500 a month. The average food stamp benefit is $133 per person. If low income people are working, they can get around $5,000 a year from the EITC for a single person with two children at the poverty level. (They would get less at lower income levels.)

These programs account for the vast majority of federal government payments to poor people. It won’t get you anywhere near David Brooks’ $14,000 per person per year, but why spoil a good story with facts?

Addendum:

Folks seem anxious to count Medicaid spending as spending on the poor. That’s fine by me. The point I was making is that we pay twice as much as people elsewhere in the world for care that is no better because doctors and other providers get paid twice as much.

That seems worth noting in an assessment of how generous we are to the poor. To take an overblown analogy, suppose terrorists took some number of poor people hostage and demanded tens of millions of dollars for their release. We can include our ransom payments as money spent on the poor and say again how generous we are.

In this case, the folks playing the role of the terrorists in making big money demands are the doctors and other health care providers. In other words, they are David Brooks’ cardiologist neighbor who gets well over $400,000 a year in large part due to payments from the government. You’re welcome to see this as generosity to the poor, I see it as generosity to David Brooks’ cardiologist neighbor.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Actually, I don’t know that he is, but he would be if he were consistent. Earlier in the week, he complained that I thought there should be rules on currency manipulation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The gist of his argument is that if another country wants to deliberately under-value its currency, so that we can buy their exports at a lower price, our response should be “thank you very much.” In effect the currency manipulator is subsidizing our consumption.

This is of course true and the same logic applies to export subsidies. If Japan, Australia, or some other country wants to provide a 20 percent subsidy on exports of cars, computers, or other goods and services, then they are making those items cheaper for U.S. consumers. Worstall would presumably want us to say “thank you very much” and leave it at that.

But those dunderheads negotiating the TPP are banning export subsidies. They will make it a trade violation if Australia wants to subsidize our consumers. I assume Worstall is very angry about this.

There are two points here. First there is a small one about optimal allocations in the economists’ perfect world of full employment. Even though U.S. consumers may benefit in this world from the stupidity of other countries subsidizing our consumption through their export subsidies, this is not an optimal allocation. In principle, the world economy would be larger if governments did not subsidize exports and instead let the market make allocations. Note, this argument applies with equal force to currency values that are deliberately set below market rates by governments seeking trade advantages.

The other more important point is that we’re typically not living in the economists’ perfect world of full employment, and certainly have not been there lately. In a context of an economy that is below full employment, both an export subsidy and under-valued currency have the effect of increasing the U.S. trade deficit and reducing U.S. employment. (There appears to be some serious confusion on trade and jobs by Worstall and his friends. If foreigners use the dollars they get from their exports to buy U.S. government bonds, shares or U.S. stock, or real estate, it does not create jobs in the United States, except for the small number of people involved in the sale of financial assets.)

Anyhow, in the world where we live there can be, and is now, a very direct link between the trade deficit and jobs. If we run a larger trade deficit, neither Worstall nor his friends have some magic formula that can fill the gap in demand that would be created. This is why it is important to have rules in the TPP on currency values. We simply have no mechanism for replacing the demand we are losing through a $500 billion plus annual trade deficit.

Addendum:

I see Tim has responded. I think I see the problem. Tim seems to believe the economy is always at full employment so that lack of demand is not a problem. If the economy were always at full employment, he would of course be right. There is no obvious reason we shouldn’t be happy if other countries are willing to subsidize our consumption. (There may still be some issues about market power and potential monopolization, but we can skip those for now.)

However in the world I live, the economy is often nowhere near full employment. This means that anything that reduces demand (like a larger trade deficit due to a rise in the value of the dollar) reduce output and employment. We can offset this loss of jobs and output through larger government budget deficits, but as a practical matter, we don’t. This is why I am concerned about an over-valued currency, but if I thought unemployment wasn’t a problem, I’d be with Tim.

Actually, I don’t know that he is, but he would be if he were consistent. Earlier in the week, he complained that I thought there should be rules on currency manipulation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The gist of his argument is that if another country wants to deliberately under-value its currency, so that we can buy their exports at a lower price, our response should be “thank you very much.” In effect the currency manipulator is subsidizing our consumption.

This is of course true and the same logic applies to export subsidies. If Japan, Australia, or some other country wants to provide a 20 percent subsidy on exports of cars, computers, or other goods and services, then they are making those items cheaper for U.S. consumers. Worstall would presumably want us to say “thank you very much” and leave it at that.

But those dunderheads negotiating the TPP are banning export subsidies. They will make it a trade violation if Australia wants to subsidize our consumers. I assume Worstall is very angry about this.

There are two points here. First there is a small one about optimal allocations in the economists’ perfect world of full employment. Even though U.S. consumers may benefit in this world from the stupidity of other countries subsidizing our consumption through their export subsidies, this is not an optimal allocation. In principle, the world economy would be larger if governments did not subsidize exports and instead let the market make allocations. Note, this argument applies with equal force to currency values that are deliberately set below market rates by governments seeking trade advantages.

The other more important point is that we’re typically not living in the economists’ perfect world of full employment, and certainly have not been there lately. In a context of an economy that is below full employment, both an export subsidy and under-valued currency have the effect of increasing the U.S. trade deficit and reducing U.S. employment. (There appears to be some serious confusion on trade and jobs by Worstall and his friends. If foreigners use the dollars they get from their exports to buy U.S. government bonds, shares or U.S. stock, or real estate, it does not create jobs in the United States, except for the small number of people involved in the sale of financial assets.)

Anyhow, in the world where we live there can be, and is now, a very direct link between the trade deficit and jobs. If we run a larger trade deficit, neither Worstall nor his friends have some magic formula that can fill the gap in demand that would be created. This is why it is important to have rules in the TPP on currency values. We simply have no mechanism for replacing the demand we are losing through a $500 billion plus annual trade deficit.

Addendum:

I see Tim has responded. I think I see the problem. Tim seems to believe the economy is always at full employment so that lack of demand is not a problem. If the economy were always at full employment, he would of course be right. There is no obvious reason we shouldn’t be happy if other countries are willing to subsidize our consumption. (There may still be some issues about market power and potential monopolization, but we can skip those for now.)

However in the world I live, the economy is often nowhere near full employment. This means that anything that reduces demand (like a larger trade deficit due to a rise in the value of the dollar) reduce output and employment. We can offset this loss of jobs and output through larger government budget deficits, but as a practical matter, we don’t. This is why I am concerned about an over-valued currency, but if I thought unemployment wasn’t a problem, I’d be with Tim.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Takeda, a Japanese drug company, agreed to pay $2.4 billion to settle suits claiming it concealed evidence that its diabetes drug, Actos, increased the risk of cancer. Concealing evidence of a drug’s dangers is a predictable result of government-granted patent monopolies. Since patent monopolies allow drug companies to sell their products at prices that are often several thousand percent above the free market price, they provide drug companies an enormous incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. The damage caused as a result of these misrepresentations is likely comparable to the amount of research financed through patent monopolies.

Typos corrected, thanks to Robert Salzberg.

Takeda, a Japanese drug company, agreed to pay $2.4 billion to settle suits claiming it concealed evidence that its diabetes drug, Actos, increased the risk of cancer. Concealing evidence of a drug’s dangers is a predictable result of government-granted patent monopolies. Since patent monopolies allow drug companies to sell their products at prices that are often several thousand percent above the free market price, they provide drug companies an enormous incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. The damage caused as a result of these misrepresentations is likely comparable to the amount of research financed through patent monopolies.

Typos corrected, thanks to Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT has a column today by Uki Goni, warning of the bad things that will face Greece if it defaults. The default by Argentina in December of 2001 provides the basis for his warnings.

“Economic activity was paralyzed, supermarket prices soared and pharmaceutical companies withdrew their products as the peso lost three-quarters of its value against the dollar. With private medical insurance firms virtually bankrupt and the public health system on the brink of collapse, badly needed drugs for cancer, H.I.V. and heart conditions soon became scarce. Insulin for the country’s estimated 300,000 diabetics disappeared from drugstore shelves.

“With the economy in free fall, about half the country’s population was below the poverty line.”

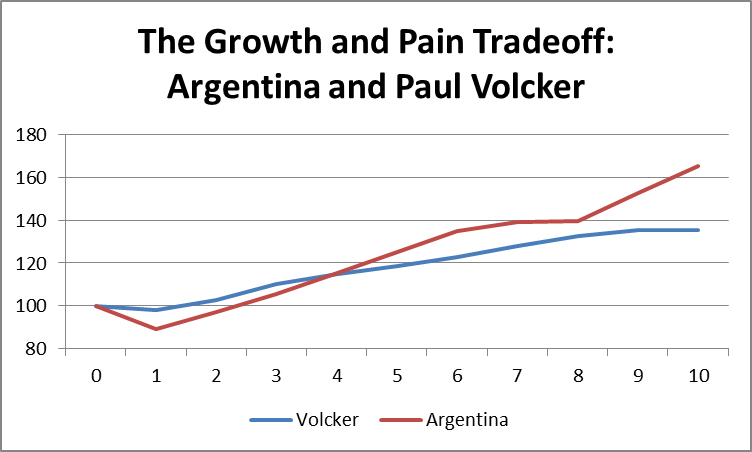

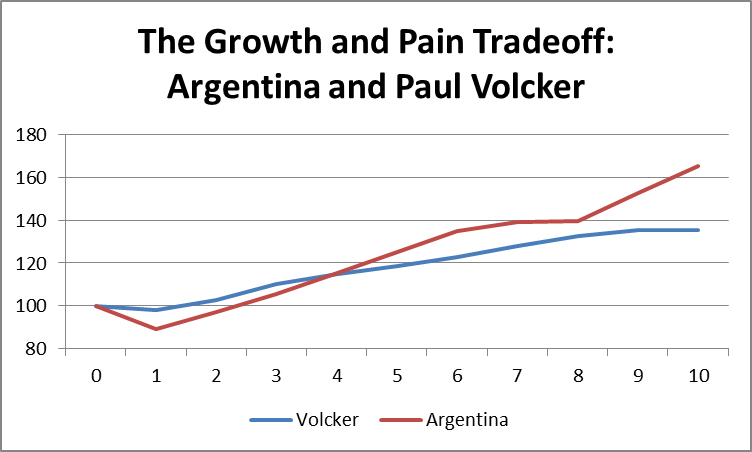

There is no doubt that the people of Argentina suffered serious hardship due to the default. However it is important to recognize that they were suffering severe hardship even before the default. The economy contracted by 8.4 percent since its peak in 1998, and contracted by 4.4 percent in 2001 alone. The unemployment rate had risen to more than 19.0 percent. Even worse, there was no end in sight.

There is no doubt that 2002 was worse for the people of Argentina as a result of the default, but by the second half of the year the economy returned to growth and grew strongly for the next seven years. (There are serious issues about the accuracy of the Argentine data, but this is primarily a question for more recent years, not the initial recovery.) By the end of 2003 Argentina had made up all of the ground loss due to the default and was clearly far ahead of its stay the course path.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

This raises the question of whether the pain associated with the default was justified by the subsequent recovery. Clearly Mr. Goni thinks it is not. In this respect it is worth bringing in a hero among American policy wonks, Paul Volcker. Volcker is given enormous praise by economists (not me) for bringing on a recession in 1981 that brought inflation down from near double digit levels. This recession caused enormous pain of the sort described by Mr. Goni (people lost their houses and farms and couldn’t pay for necessary health care, unemployment rose to almost 11.0 percent), but the economy did bounce back in 1983. The vast majority of policy types think this pain was well worth it as a price to bring down inflation.

For further background, it is worth noting that the economy had been growing prior to Volcker’s decision to bring on a recession. Argentina’s economy was already contracting and virtually certain to continue to contract prior to the decision to default. In other words, there was no pain free path available to Argentina, whereas the U.S. economy likely would have continued to grow, albeit with higher inflation, without Volcker’s actions. (For cheap fun look at this paper showing the I.M.F. consistently over-projecting growth prior to default and then hugely under-projecting growth post default.)

Clearly Greece looks much more like Argentina than the United States in 1981. Its economy has already contracted by more than 20 percent, with unemployment now over 25 percent. And, there is little hope for improvement any time soon under the stay the course scenario. This should make the default route look more attractive, since the country has little to lose.

That doesn’t mean default will be pretty. People will suffer as a result, but at least default offers a better path forward. The striking takeaway from Goni’s piece is how the notion of short-term pain for long-term gain can be made to look so appalling in a case where it was almost certainly necessary, whereas a similar choice is widely applauded in the United States in a case where it almost certainly was not. (For any Brits reading this, plug in “Thatcher” for Volcker.) It would probably be rude to point out that the 1981-82 recession was associated with a sharp upward redistribution of income away from workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution.

Note: Typos fixed, thanks folks.

The NYT has a column today by Uki Goni, warning of the bad things that will face Greece if it defaults. The default by Argentina in December of 2001 provides the basis for his warnings.

“Economic activity was paralyzed, supermarket prices soared and pharmaceutical companies withdrew their products as the peso lost three-quarters of its value against the dollar. With private medical insurance firms virtually bankrupt and the public health system on the brink of collapse, badly needed drugs for cancer, H.I.V. and heart conditions soon became scarce. Insulin for the country’s estimated 300,000 diabetics disappeared from drugstore shelves.

“With the economy in free fall, about half the country’s population was below the poverty line.”

There is no doubt that the people of Argentina suffered serious hardship due to the default. However it is important to recognize that they were suffering severe hardship even before the default. The economy contracted by 8.4 percent since its peak in 1998, and contracted by 4.4 percent in 2001 alone. The unemployment rate had risen to more than 19.0 percent. Even worse, there was no end in sight.

There is no doubt that 2002 was worse for the people of Argentina as a result of the default, but by the second half of the year the economy returned to growth and grew strongly for the next seven years. (There are serious issues about the accuracy of the Argentine data, but this is primarily a question for more recent years, not the initial recovery.) By the end of 2003 Argentina had made up all of the ground loss due to the default and was clearly far ahead of its stay the course path.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

This raises the question of whether the pain associated with the default was justified by the subsequent recovery. Clearly Mr. Goni thinks it is not. In this respect it is worth bringing in a hero among American policy wonks, Paul Volcker. Volcker is given enormous praise by economists (not me) for bringing on a recession in 1981 that brought inflation down from near double digit levels. This recession caused enormous pain of the sort described by Mr. Goni (people lost their houses and farms and couldn’t pay for necessary health care, unemployment rose to almost 11.0 percent), but the economy did bounce back in 1983. The vast majority of policy types think this pain was well worth it as a price to bring down inflation.

For further background, it is worth noting that the economy had been growing prior to Volcker’s decision to bring on a recession. Argentina’s economy was already contracting and virtually certain to continue to contract prior to the decision to default. In other words, there was no pain free path available to Argentina, whereas the U.S. economy likely would have continued to grow, albeit with higher inflation, without Volcker’s actions. (For cheap fun look at this paper showing the I.M.F. consistently over-projecting growth prior to default and then hugely under-projecting growth post default.)

Clearly Greece looks much more like Argentina than the United States in 1981. Its economy has already contracted by more than 20 percent, with unemployment now over 25 percent. And, there is little hope for improvement any time soon under the stay the course scenario. This should make the default route look more attractive, since the country has little to lose.

That doesn’t mean default will be pretty. People will suffer as a result, but at least default offers a better path forward. The striking takeaway from Goni’s piece is how the notion of short-term pain for long-term gain can be made to look so appalling in a case where it was almost certainly necessary, whereas a similar choice is widely applauded in the United States in a case where it almost certainly was not. (For any Brits reading this, plug in “Thatcher” for Volcker.) It would probably be rude to point out that the 1981-82 recession was associated with a sharp upward redistribution of income away from workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution.

Note: Typos fixed, thanks folks.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I usually confine my comments to economic reporting, but I can’t let my blog sit idle when the Washington Post commits major journalistic malpractice on a story of national importance. The Post ran a major front page story with the headline, “Prisoner in van said Freddie Gray was ‘trying to injure himself’ document says.” As the article indicates, the basis for the story is a document which includes the statement by another prisoner, presumably someone still in police custody. The Post tells readers:

“The Post was given the document under the condition that the prisoner not be named because the person who provided it feared for the inmate’s safety.”

There are two big problems with this sentence. The Post does not know that the person who provided the document actually feared for the inmate’s safety. The Post knows that the person who provided the document said that they feared for the inmate’s safety. News reporters know that people sometimes do not tell the truth. This is why they report what people say, they do not tell readers that what people say is necessarily true, unless they have an independent basis for this assessment.

The other problem with this sentence is that it does not tell us why the person who provided the document is not identified. Did he/she also fear for their safety? A simple explanation would go a long way here.

It is possible that the document accurately reflects what another prisoner heard and his comments in a sworn statement, but it is also possible that this is largely fabricated. The story is obviously very helpful to the Baltimore police and since it likely originated in a context where the Baltimore police completely controlled the situation (presumably there were no independent observers when the prisoner was giving his statement) and this unidentified person controlled what was given the Post, it must be viewed with considerable skepticism.

Making this statement the basis of a front page story and not indicating to readers the need for skepticism, given the source, is incredibly irresponsible.

I usually confine my comments to economic reporting, but I can’t let my blog sit idle when the Washington Post commits major journalistic malpractice on a story of national importance. The Post ran a major front page story with the headline, “Prisoner in van said Freddie Gray was ‘trying to injure himself’ document says.” As the article indicates, the basis for the story is a document which includes the statement by another prisoner, presumably someone still in police custody. The Post tells readers:

“The Post was given the document under the condition that the prisoner not be named because the person who provided it feared for the inmate’s safety.”

There are two big problems with this sentence. The Post does not know that the person who provided the document actually feared for the inmate’s safety. The Post knows that the person who provided the document said that they feared for the inmate’s safety. News reporters know that people sometimes do not tell the truth. This is why they report what people say, they do not tell readers that what people say is necessarily true, unless they have an independent basis for this assessment.

The other problem with this sentence is that it does not tell us why the person who provided the document is not identified. Did he/she also fear for their safety? A simple explanation would go a long way here.

It is possible that the document accurately reflects what another prisoner heard and his comments in a sworn statement, but it is also possible that this is largely fabricated. The story is obviously very helpful to the Baltimore police and since it likely originated in a context where the Baltimore police completely controlled the situation (presumably there were no independent observers when the prisoner was giving his statement) and this unidentified person controlled what was given the Post, it must be viewed with considerable skepticism.

Making this statement the basis of a front page story and not indicating to readers the need for skepticism, given the source, is incredibly irresponsible.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I hate to be picking on Matt O’Brien again, but come on, this is setting the bar pretty goddamn low. He began a piece reporting on a consulting gig that Bernanke will have the bond fund Pimco by telling readers:

“If anyone deserves two seven-figure sinecures, it’s Ben Bernanke.”

I won’t go over the full indictment of Ben Bernanke and will give him credit for a reasonably good job trying to boost the economy post-crash in the wake of the outraged opposition of the right-wing, but let’s get real. The housing bubble and ensuing crash were not natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

The bubble was the result of bad policy. It is the Fed’s responsibility to prevent harmful bubbles whose crash will disrupt the economy. While Bernanke only took over as Fed chair in January of 2006, after the bubble had already grown to very dangerous levels, he was sitting at Greenspan’s side at the Fed through most of the process. (He did head over for a brief stint as head of President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers.) Through this whole period was completely dismissive of those who raised concerns about the bubble and junk loans that were fueling it.

This incredible negligence has had a devastating cost for tens of millions of people in the United States and around the world. And for this he deserves two-seven figure sinecures? This sounds like a case of the soft bigotry of incredibly low expectations.

I hate to be picking on Matt O’Brien again, but come on, this is setting the bar pretty goddamn low. He began a piece reporting on a consulting gig that Bernanke will have the bond fund Pimco by telling readers:

“If anyone deserves two seven-figure sinecures, it’s Ben Bernanke.”

I won’t go over the full indictment of Ben Bernanke and will give him credit for a reasonably good job trying to boost the economy post-crash in the wake of the outraged opposition of the right-wing, but let’s get real. The housing bubble and ensuing crash were not natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

The bubble was the result of bad policy. It is the Fed’s responsibility to prevent harmful bubbles whose crash will disrupt the economy. While Bernanke only took over as Fed chair in January of 2006, after the bubble had already grown to very dangerous levels, he was sitting at Greenspan’s side at the Fed through most of the process. (He did head over for a brief stint as head of President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers.) Through this whole period was completely dismissive of those who raised concerns about the bubble and junk loans that were fueling it.

This incredible negligence has had a devastating cost for tens of millions of people in the United States and around the world. And for this he deserves two-seven figure sinecures? This sounds like a case of the soft bigotry of incredibly low expectations.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

E.J. Dionne and Harold Meyerson both had interesting columns in the Post this morning, but they suffer from the same major error. Both note the loss of manufacturing jobs and downward pressure on the wages of non-college educated workers due to effects of trade. But both speak of this as being the result of a natural process of globalization.

This is wrong. The downward pressure on wages was the deliberate outcome of government policies designed to put U.S. manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. This was a conscious choice. Our trade deals could have been designed to put our doctors and lawyers in direct competition with much lower paid professionals in the developing world.

Trade deals could have focused on developing clear standards that would allow students in Mexico, India, and China to train to U.S. levels and then practice as professionals in the United States on the same terms as someone born in New York or Kansas. This would have provided enormous savings to consumers in the form of lower health care costs, legal fees, and professional services more generally. The argument for free trade in professional services is exactly the same as the argument for free trade in manufactured goods.

The big difference is that doctors and lawyers have much more power than autoworkers and textile workers, therefore the politicians won’t consider subjecting them to international competition. However that is no reason for columnists not to talk about this fact.

More generally, the heavy hand of government is all over the upward redistribution of the last three and a half decades. We have a Federal Reserve Board that has repeatedly raised interest rates to keep workers from getting jobs and bargaining power. A tax system that directly and explicitly subsidizes many people getting high six or even seven-figure salaries at universities, hospitals, and private charities and foundations. We have government subsidies for too big to fail banks.

Anyhow, inequality, like the path of globalization, is not something that happened. It was and is the result of conscious policy. We won’t be able to deal with it effectively until we acknowledge this simple fact.

E.J. Dionne and Harold Meyerson both had interesting columns in the Post this morning, but they suffer from the same major error. Both note the loss of manufacturing jobs and downward pressure on the wages of non-college educated workers due to effects of trade. But both speak of this as being the result of a natural process of globalization.

This is wrong. The downward pressure on wages was the deliberate outcome of government policies designed to put U.S. manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. This was a conscious choice. Our trade deals could have been designed to put our doctors and lawyers in direct competition with much lower paid professionals in the developing world.

Trade deals could have focused on developing clear standards that would allow students in Mexico, India, and China to train to U.S. levels and then practice as professionals in the United States on the same terms as someone born in New York or Kansas. This would have provided enormous savings to consumers in the form of lower health care costs, legal fees, and professional services more generally. The argument for free trade in professional services is exactly the same as the argument for free trade in manufactured goods.

The big difference is that doctors and lawyers have much more power than autoworkers and textile workers, therefore the politicians won’t consider subjecting them to international competition. However that is no reason for columnists not to talk about this fact.

More generally, the heavy hand of government is all over the upward redistribution of the last three and a half decades. We have a Federal Reserve Board that has repeatedly raised interest rates to keep workers from getting jobs and bargaining power. A tax system that directly and explicitly subsidizes many people getting high six or even seven-figure salaries at universities, hospitals, and private charities and foundations. We have government subsidies for too big to fail banks.

Anyhow, inequality, like the path of globalization, is not something that happened. It was and is the result of conscious policy. We won’t be able to deal with it effectively until we acknowledge this simple fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is an important correction to the David Ignatius’ Washington Post column touting the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as a way to revive Japan’s economy. Unlike President Bush, who published a draft text of the Free Trade of the Americas Agreement before requesting fast-track authority, President Obama has chosen to keep the draft text of the TPP secret. This is not an allegation of TPP critics, it is a fact in the world.

Another point worth mentioning in this context is that when President Obama argued that he was pushing the TPP to help U.S. drug companies, he was effectively saying that he was hurting U.S. workers. There are two reasons this is likely to be the case. Several provisions of the deal will likely raise drug prices in the United States, for example by extending the period of data exclusivity for biosimiliar drugs (12 years in the leaked draft chapter, versus 7 years now). A decision by a future Congress to have Medicare negotiate drug prices may also be a violation of rules that effectively limit countries’ ability to put in place new price controls.

The other issue is that the more money that foreigners pay Pfizer, Merck and other U.S. drug companies for their patents, the less money they will have to buy airplanes and other items produced in the United States. Unless a worker in the United States owns stock in a drug company, they would be better of if foreigners paid less for drugs rather than more. (The drug companies do employ workers, but the marginal increase in employment from higher company profits is likely to be very small.)

In terms of the effort to revive Japan’s economy, it is worth noting that OECD reports that Japan’s employment to population ratio among people between the ages of 16-64 has risen by 3.1 percentage points since 2012. The ratio in the United States has only increased by 1.4 percentage points over the same period.

That is an important correction to the David Ignatius’ Washington Post column touting the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as a way to revive Japan’s economy. Unlike President Bush, who published a draft text of the Free Trade of the Americas Agreement before requesting fast-track authority, President Obama has chosen to keep the draft text of the TPP secret. This is not an allegation of TPP critics, it is a fact in the world.

Another point worth mentioning in this context is that when President Obama argued that he was pushing the TPP to help U.S. drug companies, he was effectively saying that he was hurting U.S. workers. There are two reasons this is likely to be the case. Several provisions of the deal will likely raise drug prices in the United States, for example by extending the period of data exclusivity for biosimiliar drugs (12 years in the leaked draft chapter, versus 7 years now). A decision by a future Congress to have Medicare negotiate drug prices may also be a violation of rules that effectively limit countries’ ability to put in place new price controls.

The other issue is that the more money that foreigners pay Pfizer, Merck and other U.S. drug companies for their patents, the less money they will have to buy airplanes and other items produced in the United States. Unless a worker in the United States owns stock in a drug company, they would be better of if foreigners paid less for drugs rather than more. (The drug companies do employ workers, but the marginal increase in employment from higher company profits is likely to be very small.)

In terms of the effort to revive Japan’s economy, it is worth noting that OECD reports that Japan’s employment to population ratio among people between the ages of 16-64 has risen by 3.1 percentage points since 2012. The ratio in the United States has only increased by 1.4 percentage points over the same period.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes folks, hold on to your hats, Thomas Friedman supports the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Friedman fans will recall his famous comment:

“I was speaking out in Minnesota — my hometown, in fact — and a guy stood up in the audience, said, ‘Mr. Friedman, is there any free trade agreement you’d oppose?’ I said, ‘No, absolutely not.’ I said, ‘You know what, sir? I wrote a column supporting the CAFTA, the Caribbean Free Trade initiative. I didn’t even know what was in it. I just knew two words: free trade.'”

Actually, Friedman does provide useful insight into the issue when he cites President Obama referring to the TPP as a “effort to expand trade on our terms.” The key question is who is “our.” In these remarks President Obama made a point of mentioning the effort to increase the prices U.S. drug companies get for their drugs. That’s great news for people who own lots of stock in Merck or Pfizer, but not good news for anyone else. In addition to paying more for drugs, workers in the United States are likely to see their exports crowded out by higher royalty payments to Merck and Pfizer. This form of protectionism is likely to be a drag on growth and jobs.

In addition, the Obama administration decided not to include rules on currency values. This could have helped to address the problem of an over-valued dollar. This is the main cause of the U.S. trade deficit which remains an enormous drag on growth and obstacle to full employment. If the “our” referred to workers in the United States, currency rules likely would have been at the top of the list of items to be included.

And the investor-state dispute settlement tribunals, which will allow corporations to sue governments in the U.S. and elsewhere, is also a big triumph for corporate interests. These extra-judicial tribunals could penalize any level of government for consumer, safety, labor, or environmental regulations that are deemed harmful to foreign investors.

So Friedman may be right about “our terms,” but his “our” is likely not the “our” that includes most people in this country or the world.

Yes folks, hold on to your hats, Thomas Friedman supports the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Friedman fans will recall his famous comment:

“I was speaking out in Minnesota — my hometown, in fact — and a guy stood up in the audience, said, ‘Mr. Friedman, is there any free trade agreement you’d oppose?’ I said, ‘No, absolutely not.’ I said, ‘You know what, sir? I wrote a column supporting the CAFTA, the Caribbean Free Trade initiative. I didn’t even know what was in it. I just knew two words: free trade.'”

Actually, Friedman does provide useful insight into the issue when he cites President Obama referring to the TPP as a “effort to expand trade on our terms.” The key question is who is “our.” In these remarks President Obama made a point of mentioning the effort to increase the prices U.S. drug companies get for their drugs. That’s great news for people who own lots of stock in Merck or Pfizer, but not good news for anyone else. In addition to paying more for drugs, workers in the United States are likely to see their exports crowded out by higher royalty payments to Merck and Pfizer. This form of protectionism is likely to be a drag on growth and jobs.

In addition, the Obama administration decided not to include rules on currency values. This could have helped to address the problem of an over-valued dollar. This is the main cause of the U.S. trade deficit which remains an enormous drag on growth and obstacle to full employment. If the “our” referred to workers in the United States, currency rules likely would have been at the top of the list of items to be included.

And the investor-state dispute settlement tribunals, which will allow corporations to sue governments in the U.S. and elsewhere, is also a big triumph for corporate interests. These extra-judicial tribunals could penalize any level of government for consumer, safety, labor, or environmental regulations that are deemed harmful to foreign investors.

So Friedman may be right about “our terms,” but his “our” is likely not the “our” that includes most people in this country or the world.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The economist Barbara Bergmann died last week. There is a memorial service on Tuesday which I will not be able to attend because of another commitment, but I did want to say a few words.

Barbara was an extraordinary person. She got her PhD in economics in the early 1960s; a time when virtually no women entered the profession. She made extensive contributions to the field, most of them in the area of gender economics.

I first encountered Barbara back in the 1980s when I was a grad student at the University of Michigan. She gave a talk in which she explained testimony she had given in a case on gender discrimination in annuities. Prior to this case, insurance companies usually made lower annual payouts to women than men, based on the fact that women had longer life expectancies. The case in which Barbara gave her testimony overturned this practice after the Supreme Court ruled it was illegal discrimination.

Barbara explained the nature of her argument by pointing out that there was huge overlap in the distribution of longevity between men and women. Women had longer life-spans on average mostly because a relatively small number of women lived very long lives. She argued that it didn’t make sense to give lower annuities to all women because of these long-lived women.

During the question period, many of the faculty were upset by the nature of this argument. After all, women did on average live longer than men, why shouldn’t insurers adjust for this fact in their annual payouts?

Barbara responded by making the case more extreme. She suggested a scenario in which the distribution of lifespans was identical for men and women, except for one person (I believe Barbara referred to her as a “pest”) who refused to die. We then check the DNA of this person and it turns out that she is a women. Would it then make sense to reduce the annuities for all women based on this fact?

After the lecture, a number of the grad students were arguing over this issue. Most seemed to share the view of our faculty, that the differences in annuities was justified by women’s longer life expectancies. Then someone suggested that African Americans should get larger annuities than whites, since they have shorter life expectancies. Several of the advocates of lower payments for women immediately jumped on this as race discrimination. (Yes, everyone was white.)

This episode taught me a lot about economists, if not economics. Barbara will be missed.

The economist Barbara Bergmann died last week. There is a memorial service on Tuesday which I will not be able to attend because of another commitment, but I did want to say a few words.

Barbara was an extraordinary person. She got her PhD in economics in the early 1960s; a time when virtually no women entered the profession. She made extensive contributions to the field, most of them in the area of gender economics.

I first encountered Barbara back in the 1980s when I was a grad student at the University of Michigan. She gave a talk in which she explained testimony she had given in a case on gender discrimination in annuities. Prior to this case, insurance companies usually made lower annual payouts to women than men, based on the fact that women had longer life expectancies. The case in which Barbara gave her testimony overturned this practice after the Supreme Court ruled it was illegal discrimination.

Barbara explained the nature of her argument by pointing out that there was huge overlap in the distribution of longevity between men and women. Women had longer life-spans on average mostly because a relatively small number of women lived very long lives. She argued that it didn’t make sense to give lower annuities to all women because of these long-lived women.

During the question period, many of the faculty were upset by the nature of this argument. After all, women did on average live longer than men, why shouldn’t insurers adjust for this fact in their annual payouts?

Barbara responded by making the case more extreme. She suggested a scenario in which the distribution of lifespans was identical for men and women, except for one person (I believe Barbara referred to her as a “pest”) who refused to die. We then check the DNA of this person and it turns out that she is a women. Would it then make sense to reduce the annuities for all women based on this fact?

After the lecture, a number of the grad students were arguing over this issue. Most seemed to share the view of our faculty, that the differences in annuities was justified by women’s longer life expectancies. Then someone suggested that African Americans should get larger annuities than whites, since they have shorter life expectancies. Several of the advocates of lower payments for women immediately jumped on this as race discrimination. (Yes, everyone was white.)

This episode taught me a lot about economists, if not economics. Barbara will be missed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión