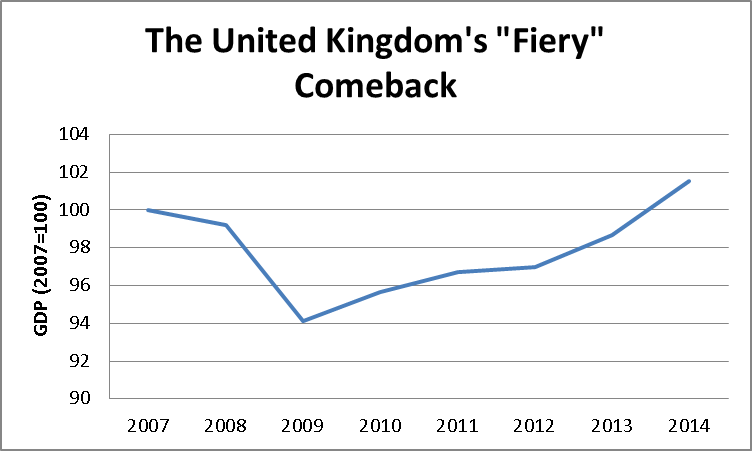

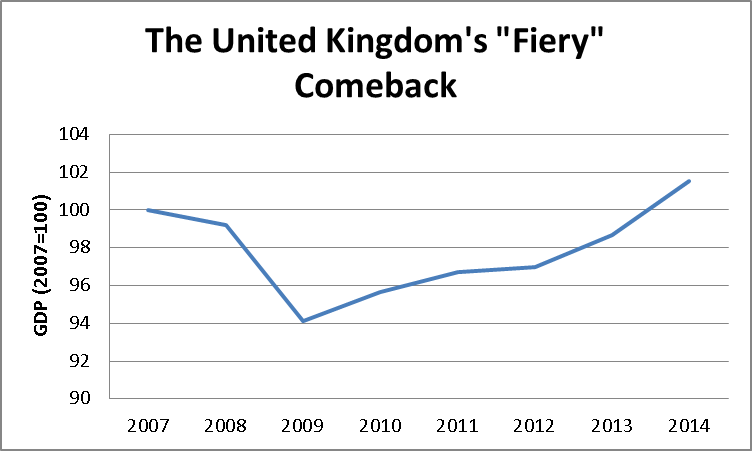

When countries went into recessions in the past they usually came out with a year or two of rapid growth that more than made up the ground lost in the recession and then resumed a normal growth path until the next recession. That hasn’t been the case in any major wealthy country following the 2008 downturn, although some countries, notably those in the euro zone, have done markedly worse than others.

Perhaps it is this comparison to the weak performance of the euro zone countries that led a piece in the NYT Dealbook section to tell readers:

“Britons also see a Continent that is plagued by deflation and stagnation while their economy has staged a fiery comeback from the financial crisis.”

According to the I.M.F. the U.K. economy will be 1.5 percent larger in 2014 than it was in 2007. This would be equal to a bit more than a half year of growth in normal times.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

It is also worth noting that this piece seems to imply that the loss of part of its financial sector would be a big hit to the U.K. economy. This is not clear. Economists usually assume that economies tend to be at their full employment level of output in the long-run. If this is the case, then the loss of banks in the U.K. and/or Scotland would lead the people currently employed in finance to move to other sectors where their labor could be employed productively.

When countries went into recessions in the past they usually came out with a year or two of rapid growth that more than made up the ground lost in the recession and then resumed a normal growth path until the next recession. That hasn’t been the case in any major wealthy country following the 2008 downturn, although some countries, notably those in the euro zone, have done markedly worse than others.

Perhaps it is this comparison to the weak performance of the euro zone countries that led a piece in the NYT Dealbook section to tell readers:

“Britons also see a Continent that is plagued by deflation and stagnation while their economy has staged a fiery comeback from the financial crisis.”

According to the I.M.F. the U.K. economy will be 1.5 percent larger in 2014 than it was in 2007. This would be equal to a bit more than a half year of growth in normal times.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

It is also worth noting that this piece seems to imply that the loss of part of its financial sector would be a big hit to the U.K. economy. This is not clear. Economists usually assume that economies tend to be at their full employment level of output in the long-run. If this is the case, then the loss of banks in the U.K. and/or Scotland would lead the people currently employed in finance to move to other sectors where their labor could be employed productively.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Allan Sloan raises an important point about winners and losers from corporate inversions, the process through which a U.S. company arranges to be taken over by a foreign company to lower its tax bill. He points out that many shareholders will be hit with a large individual tax bill because as an accounting matter they will have sold their stock and thereby realized a capital gain.

This isn’t a question of shedding tears for these shareholders, who will mostly be in the top tenth or even the top one percent of the income distribution. The point is that this tax scam is not in their interest. While the company may benefit over time from paying lower corporate taxes, this is unlikely to result in a net gain for those current shareholders who have to pay capital gains taxes because of the inversion.

Sloan points out that the big gainers are the financial firms that arrange the deals, who can count on hundreds of millions in fees from a major deal. The corporate insiders (top management) may also stand to gain since they are unlikely to be faced with the problem of having to pay taxes on large amounts of unrealized capital gains.

If the point is to change practices such as corporate inversions, rather than just complain about them, it is important to recognize these distinctions. The financial sector and the corporate insiders are incredibly powerful interest groups. If some number of wealthy shareholders can be brought into a coalition to restrict this sort of tax gaming, it would have a far greater chance of succeeding. (The same story applies to bloated CEO pay, which most immediately is money out of shareholders’ pockets.)

Allan Sloan raises an important point about winners and losers from corporate inversions, the process through which a U.S. company arranges to be taken over by a foreign company to lower its tax bill. He points out that many shareholders will be hit with a large individual tax bill because as an accounting matter they will have sold their stock and thereby realized a capital gain.

This isn’t a question of shedding tears for these shareholders, who will mostly be in the top tenth or even the top one percent of the income distribution. The point is that this tax scam is not in their interest. While the company may benefit over time from paying lower corporate taxes, this is unlikely to result in a net gain for those current shareholders who have to pay capital gains taxes because of the inversion.

Sloan points out that the big gainers are the financial firms that arrange the deals, who can count on hundreds of millions in fees from a major deal. The corporate insiders (top management) may also stand to gain since they are unlikely to be faced with the problem of having to pay taxes on large amounts of unrealized capital gains.

If the point is to change practices such as corporate inversions, rather than just complain about them, it is important to recognize these distinctions. The financial sector and the corporate insiders are incredibly powerful interest groups. If some number of wealthy shareholders can be brought into a coalition to restrict this sort of tax gaming, it would have a far greater chance of succeeding. (The same story applies to bloated CEO pay, which most immediately is money out of shareholders’ pockets.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Are you scared? How will we pay for that? This is the context that was missing from the discussion of a bill from Utah Senator Orin Hatch which would encourage state and local governments to replace traditional defined benefit pension plans with cash balance type plans tied to an annuity which would be run by the insurance industry.

The piece told readers:

“For local governments and states, the unfunded liabilities are huge, ranging anywhere from $1.4 trillion to more than $4 trillion, depending on the assumptions plugged in by actuaries.”

These shortfalls are calculated over the pension plans’ thirty year planning horizon, a period in which the discounted value of GDP will be in the neighborhood of $500 trillion. It is unlikely that many readers have a clear sense of the projected size of the economy over this period, so they have little basis for assessing these projected shortfalls. If they did know the projected size of the economy they may disagree with the characterization of the shortfall as “huge.” (The difference between the two numbers is based on whether the pension funds calculate their shortfalls assuming that their assets earn their projected rate of return or whether they calculate their shortfall assuming their assets earn the return available on a completely safe asset like government bonds.)

There are a few other points worth noting about this picture. First, the shortfalls are likely to be considerably less next year. Most pensions calculate their current assets using a five year average. Next year 2014 will replace 2009. Unless the stock market plunges in the last three and a half months of the year, this change will lead to a substantial improvement in the funding situation of most pensions.

The second point is that the averages conceal sharp divergences across funds. Most pension funds are reasonably well-funded, with some having funding ratios of over 100 percent. There are a number of outliers, like Illinois, Ohio, and New Jersey, that have badly underfunded plans. This is not due to their investment patterns, but rather their repeated failure to make required contributions.

Finally, it is worth noting that turning over the pension plan to insurance companies will almost certainly raise the fees collected by the financial industry. This means that the same amount of taxpayer dollars will translate into lower benefits on average for retirees. That’s obviously good news for the insurance industry, but bad news for taxpayers and public sector workers.

There is one possible policy justification for throwing this money in the garbage. If an insurance company was an intermediary, it might be more difficult for politicians like New Jersey Governor Chris Christie to avoid making required contributions. As it stands now, the refusal to make these contributions appears to be part of Mr. Christie’s political shtick, allowing him to portray himself as a tough guy standing up to the state’s workers.

If there was an insurance company acting as an intermediary then perhaps the situation may be clearer to the public. Mr. Christie is simply trying to avoid paying bills that he has accrued, effectively stealing money from the state’s workers.

Are you scared? How will we pay for that? This is the context that was missing from the discussion of a bill from Utah Senator Orin Hatch which would encourage state and local governments to replace traditional defined benefit pension plans with cash balance type plans tied to an annuity which would be run by the insurance industry.

The piece told readers:

“For local governments and states, the unfunded liabilities are huge, ranging anywhere from $1.4 trillion to more than $4 trillion, depending on the assumptions plugged in by actuaries.”

These shortfalls are calculated over the pension plans’ thirty year planning horizon, a period in which the discounted value of GDP will be in the neighborhood of $500 trillion. It is unlikely that many readers have a clear sense of the projected size of the economy over this period, so they have little basis for assessing these projected shortfalls. If they did know the projected size of the economy they may disagree with the characterization of the shortfall as “huge.” (The difference between the two numbers is based on whether the pension funds calculate their shortfalls assuming that their assets earn their projected rate of return or whether they calculate their shortfall assuming their assets earn the return available on a completely safe asset like government bonds.)

There are a few other points worth noting about this picture. First, the shortfalls are likely to be considerably less next year. Most pensions calculate their current assets using a five year average. Next year 2014 will replace 2009. Unless the stock market plunges in the last three and a half months of the year, this change will lead to a substantial improvement in the funding situation of most pensions.

The second point is that the averages conceal sharp divergences across funds. Most pension funds are reasonably well-funded, with some having funding ratios of over 100 percent. There are a number of outliers, like Illinois, Ohio, and New Jersey, that have badly underfunded plans. This is not due to their investment patterns, but rather their repeated failure to make required contributions.

Finally, it is worth noting that turning over the pension plan to insurance companies will almost certainly raise the fees collected by the financial industry. This means that the same amount of taxpayer dollars will translate into lower benefits on average for retirees. That’s obviously good news for the insurance industry, but bad news for taxpayers and public sector workers.

There is one possible policy justification for throwing this money in the garbage. If an insurance company was an intermediary, it might be more difficult for politicians like New Jersey Governor Chris Christie to avoid making required contributions. As it stands now, the refusal to make these contributions appears to be part of Mr. Christie’s political shtick, allowing him to portray himself as a tough guy standing up to the state’s workers.

If there was an insurance company acting as an intermediary then perhaps the situation may be clearer to the public. Mr. Christie is simply trying to avoid paying bills that he has accrued, effectively stealing money from the state’s workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal devoted a major article to the efforts by President Obama and several governors to address the skills gap. According to the piece, employers in manufacturing can’t hire workers with the right skills. If employers can’t get enough workers then we would expect to see wages rising in manufacturing.

They aren’t. Over the last year the average hourly wage rose by just 2.1 percent, only a little higher than the inflation rate and slightly less than the average for all workers. This follows several years where wages in manufacturing rose less than the economy-wide average.

Change in Average Hourly Wage in Manufacturing Over Prior 12 Months

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There are workers who have the skills employers need. They work for their competitors. If an employer wants to hire people she can get them away from competitors by offering a higher wage. It seems that employers in the manufacturing sector may need this simple lesson in market economic to solve their skills shortage problem.

The Wall Street Journal devoted a major article to the efforts by President Obama and several governors to address the skills gap. According to the piece, employers in manufacturing can’t hire workers with the right skills. If employers can’t get enough workers then we would expect to see wages rising in manufacturing.

They aren’t. Over the last year the average hourly wage rose by just 2.1 percent, only a little higher than the inflation rate and slightly less than the average for all workers. This follows several years where wages in manufacturing rose less than the economy-wide average.

Change in Average Hourly Wage in Manufacturing Over Prior 12 Months

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There are workers who have the skills employers need. They work for their competitors. If an employer wants to hire people she can get them away from competitors by offering a higher wage. It seems that employers in the manufacturing sector may need this simple lesson in market economic to solve their skills shortage problem.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Nope, I’m not kidding. We’ve seen a sharp slowdown in health care costs across the board over the last seven years. This has led the Congressional Budget Office to lower its deficit projections. In fact, the reductions in projected deficits due to this slowdown has been sharper than the reductions that we might have seen as a result of almost any politically plausible cut in benefits. But Robert Samuelson is not happy. He tells readers:

“No one truly grasps why Medicare spending has slowed so abruptly. A detailed CBO study threw cold water on many plausible explanations. What we don’t understand could easily reverse.”

In other words, just because the problem seems to be going away doesn’t mean we still shouldn’t make cuts to benefits. One factor that may lead us to believe that lower cost growth can be maintained is that the United States still pays more than twice as much per person for its care with nothing to show for it in terms of outcomes. In fact, if our costs were the same as those in any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

The difference in costs is attributable to the fact that our doctors, drug companies, and other providers get paid twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. Of course these are all very powerful lobbies so we more often hear about proposals to cut benefits for seniors rather than reduce the money being paid to providers.

As noted before, since Social Security payments come from a designated tax, there is no real way to get money for the rest of Samuelson’s agenda unless we tax people for Social Security and then use the money for the military or other purposes. Such a scheme is not likely to be very popular and few politicians are willing to openly advocate it.

Nope, I’m not kidding. We’ve seen a sharp slowdown in health care costs across the board over the last seven years. This has led the Congressional Budget Office to lower its deficit projections. In fact, the reductions in projected deficits due to this slowdown has been sharper than the reductions that we might have seen as a result of almost any politically plausible cut in benefits. But Robert Samuelson is not happy. He tells readers:

“No one truly grasps why Medicare spending has slowed so abruptly. A detailed CBO study threw cold water on many plausible explanations. What we don’t understand could easily reverse.”

In other words, just because the problem seems to be going away doesn’t mean we still shouldn’t make cuts to benefits. One factor that may lead us to believe that lower cost growth can be maintained is that the United States still pays more than twice as much per person for its care with nothing to show for it in terms of outcomes. In fact, if our costs were the same as those in any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses, not deficits.

The difference in costs is attributable to the fact that our doctors, drug companies, and other providers get paid twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. Of course these are all very powerful lobbies so we more often hear about proposals to cut benefits for seniors rather than reduce the money being paid to providers.

As noted before, since Social Security payments come from a designated tax, there is no real way to get money for the rest of Samuelson’s agenda unless we tax people for Social Security and then use the money for the military or other purposes. Such a scheme is not likely to be very popular and few politicians are willing to openly advocate it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT editorial on Japan’s economy may have created false alarms by noting that its economy shrank at a 7.2 percent annual rate in the second quarter. This is true, but it is important to point out this plunge followed a first quarter in which it grew at a 6.0 percent annual rate. The net for the first two quarters is still negative, and the editorial is correct to raise warnings about the impact of sales tax increases on growth, but the picture is not nearly as dire as the second quarter figure taken in isolation suggests.

While the piece also reasonably calls for Japan to remove obstacles to women working and to advancing in the corporate hierarchy, it is worth noting that the country has already made substantial progress in this area. According to the OECD, the employment rate for prime age women (ages 25-54) is actually somewhat higher in Japan than in the United States, 71.4 percent in Japan compared to 69.9 percent in the United States.

A NYT editorial on Japan’s economy may have created false alarms by noting that its economy shrank at a 7.2 percent annual rate in the second quarter. This is true, but it is important to point out this plunge followed a first quarter in which it grew at a 6.0 percent annual rate. The net for the first two quarters is still negative, and the editorial is correct to raise warnings about the impact of sales tax increases on growth, but the picture is not nearly as dire as the second quarter figure taken in isolation suggests.

While the piece also reasonably calls for Japan to remove obstacles to women working and to advancing in the corporate hierarchy, it is worth noting that the country has already made substantial progress in this area. According to the OECD, the employment rate for prime age women (ages 25-54) is actually somewhat higher in Japan than in the United States, 71.4 percent in Japan compared to 69.9 percent in the United States.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post thinks its fantastic that Rhode Island broke its contract with its workers. It applauded State Treasurer and now Democratic gubernatorial nominee Gina Raimondo for not only cutting pension benefits for new hires and younger workers, but also:

“suspending annual cost-of-living increases for retirees and shifting workers to a hybrid system combining traditional pensions with 401(k)-style accounts.”

In other words, Ms. Raimondo pushed legislation that broke the state’s contract with its public employees. The Post’s argument is that these pensions were expensive and the state couldn’t afford them. This is not clear. (The Post again played the Really Big Number game telling readers about the $1 trillion projected shortfall in state pensions. That is a really big number and is supposed to scare readers. If it was interested in informing readers it would have told them the shortfall is equal to about 0.2 percent of projected GDP over the thirty year planning horizon of public pensions.)

Anyhow, if the state of Rhode Island really can’t afford to pay its bills, why should public sector workers be the only ones to pay the price. The state has hundreds or even thousands of contractors. Why not short them all 10 or 20 percent of their payments? That would be the fairest way to deal with the situation if the state really can’t pay its bills or raise the taxes needed to do so. Obviously the Post doesn’t believe that contracts with workers are real contracts.

The Washington Post thinks its fantastic that Rhode Island broke its contract with its workers. It applauded State Treasurer and now Democratic gubernatorial nominee Gina Raimondo for not only cutting pension benefits for new hires and younger workers, but also:

“suspending annual cost-of-living increases for retirees and shifting workers to a hybrid system combining traditional pensions with 401(k)-style accounts.”

In other words, Ms. Raimondo pushed legislation that broke the state’s contract with its public employees. The Post’s argument is that these pensions were expensive and the state couldn’t afford them. This is not clear. (The Post again played the Really Big Number game telling readers about the $1 trillion projected shortfall in state pensions. That is a really big number and is supposed to scare readers. If it was interested in informing readers it would have told them the shortfall is equal to about 0.2 percent of projected GDP over the thirty year planning horizon of public pensions.)

Anyhow, if the state of Rhode Island really can’t afford to pay its bills, why should public sector workers be the only ones to pay the price. The state has hundreds or even thousands of contractors. Why not short them all 10 or 20 percent of their payments? That would be the fairest way to deal with the situation if the state really can’t pay its bills or raise the taxes needed to do so. Obviously the Post doesn’t believe that contracts with workers are real contracts.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT Magazine had a piece asking whether subprime mortgages are coming back. The gist of the argument is taken from an Urban Institute study arguing that if we had the same lending standards in place as in 2001, there would have been 1.2 million more purchase mortgages issued in 2012. It goes on to tell readers that reduced sales are holding back the housing market and the recovery. All of these claims are questionable.

First, asserting that 2001 is an appropriate base of comparison is rather dubious. House prices were already rising considerably faster than the rate of inflation, breaking with their long-term trend. Furthermore, the number of home sales had increased hugely from the mid-1990s, which were also years of relative prosperity. If the Urban Institute study had used the period 1993-1995 as its base, before the beginning of the bubble, it would have found few or no missing mortgages. It is a rather herioic assumption to pick a year of extraordinarily high home sales and treat this as the reference point for future policy.

The idea that we should expect more sales to be a big trigger for the economy is also dubious. The factor that determines building is house prices. House prices are already more than 20 percent above their trend levels. There is no reason that we should expect prices to go still higher or even that they would necessarily stay as high as they are now. One factor that is likely suppressing construction is the fact that vacancy rates are still above normal levels. It is understandable that builders would be reluctant to build new housing in a context where there are still many vacant units available.

Finally, it is worth noting that it is not clear that many people are being harmed by not being able to get a mortgage. As the piece notes, the benefits of homeownership are often overstated. With prices already at historically high levels, homebuyers have a substantial risk of price declines and little reason to expect that the price of their home will rise by more than the rate of inflation.

Furthermore, there are large transactions costs associated with buying and selling a home, with the combined buying and selling costs equal to roughly 10 percent of the purchase price. This means that people who move within 3-4 years of buying a home will likely lose on the deal. This is an especially important point if the marginal homebuyers are younger people who are likely to have less stable family and employment situations.

The latter point is especially important in a context where much of the elite is demanding that the Fed raise interest rates to slow job growth. If the labor market does not improve much further, then it is likely that many people will find themselves in a situation where they have to move to get a job. That is not a good situation for a homeowner to be in.

The NYT Magazine had a piece asking whether subprime mortgages are coming back. The gist of the argument is taken from an Urban Institute study arguing that if we had the same lending standards in place as in 2001, there would have been 1.2 million more purchase mortgages issued in 2012. It goes on to tell readers that reduced sales are holding back the housing market and the recovery. All of these claims are questionable.

First, asserting that 2001 is an appropriate base of comparison is rather dubious. House prices were already rising considerably faster than the rate of inflation, breaking with their long-term trend. Furthermore, the number of home sales had increased hugely from the mid-1990s, which were also years of relative prosperity. If the Urban Institute study had used the period 1993-1995 as its base, before the beginning of the bubble, it would have found few or no missing mortgages. It is a rather herioic assumption to pick a year of extraordinarily high home sales and treat this as the reference point for future policy.

The idea that we should expect more sales to be a big trigger for the economy is also dubious. The factor that determines building is house prices. House prices are already more than 20 percent above their trend levels. There is no reason that we should expect prices to go still higher or even that they would necessarily stay as high as they are now. One factor that is likely suppressing construction is the fact that vacancy rates are still above normal levels. It is understandable that builders would be reluctant to build new housing in a context where there are still many vacant units available.

Finally, it is worth noting that it is not clear that many people are being harmed by not being able to get a mortgage. As the piece notes, the benefits of homeownership are often overstated. With prices already at historically high levels, homebuyers have a substantial risk of price declines and little reason to expect that the price of their home will rise by more than the rate of inflation.

Furthermore, there are large transactions costs associated with buying and selling a home, with the combined buying and selling costs equal to roughly 10 percent of the purchase price. This means that people who move within 3-4 years of buying a home will likely lose on the deal. This is an especially important point if the marginal homebuyers are younger people who are likely to have less stable family and employment situations.

The latter point is especially important in a context where much of the elite is demanding that the Fed raise interest rates to slow job growth. If the labor market does not improve much further, then it is likely that many people will find themselves in a situation where they have to move to get a job. That is not a good situation for a homeowner to be in.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT tolds readers that Google is the victim of a European backlash against U.S. technological dominance. In addition to anti-trust and privacy issues being raised with regard to Google, the piece also notes that Apple and Amazon are being investigated for their tax practices, taxi drivers have protested against Uber, and Facebook is being investigated for anti-trust violations.

It’s not clear that any of this amounts to an anti-American backlash. Apple and Amazon constantly face tax issues in the United States as well. Taxi drivers in the United States have protested Uber. And it would not be surprising if both Facebook and Google face anti-trust issues here as well.

But the last two paragraphs go furthest to undermine the European backlash story:

“Then there is Microsoft, Google’s longtime nemesis, which spends three times as much in Europe on lobbying and similar efforts. ICOMP, a Microsoft-backed group, has long targeted Google.

“‘Google is clearly in the cross hairs,’ said David Wood, a London-based partner at Gibson, Dunn, one of Microsoft’s law firms, and legal counsel at ICOMP. ‘A lot of the aura has faded, and the shine has come off, and people don’t think they’re the good guy anymore.'”

Companies often try to use government regulation to hamper their competitors. It is not clear that anything about the actions against Google reflect the “European backlash” promised in the headline as opposed to the sort of opposition that any large company would likely face regardless of the country in which its headquarters are located.

The NYT tolds readers that Google is the victim of a European backlash against U.S. technological dominance. In addition to anti-trust and privacy issues being raised with regard to Google, the piece also notes that Apple and Amazon are being investigated for their tax practices, taxi drivers have protested against Uber, and Facebook is being investigated for anti-trust violations.

It’s not clear that any of this amounts to an anti-American backlash. Apple and Amazon constantly face tax issues in the United States as well. Taxi drivers in the United States have protested Uber. And it would not be surprising if both Facebook and Google face anti-trust issues here as well.

But the last two paragraphs go furthest to undermine the European backlash story:

“Then there is Microsoft, Google’s longtime nemesis, which spends three times as much in Europe on lobbying and similar efforts. ICOMP, a Microsoft-backed group, has long targeted Google.

“‘Google is clearly in the cross hairs,’ said David Wood, a London-based partner at Gibson, Dunn, one of Microsoft’s law firms, and legal counsel at ICOMP. ‘A lot of the aura has faded, and the shine has come off, and people don’t think they’re the good guy anymore.'”

Companies often try to use government regulation to hamper their competitors. It is not clear that anything about the actions against Google reflect the “European backlash” promised in the headline as opposed to the sort of opposition that any large company would likely face regardless of the country in which its headquarters are located.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s not exactly news, but Neil Irwin does a nice job summarizing the data in the Fed’s new Survey of Consumer Finance. The item that many may find surprising is that median wealth was lower in 2013 than it was in 2010 is spite of the boom in the stock market over this period. As Irwin explains, this is due to the fact that most middle income families own little or no stock, even indirectly through mutual funds in retirement accounts.

For people near the middle of the income distribution their wealth is their house. In 2010 house prices were still headed downward. The first-time homebuyers tax credit had temporarily pushed up prices. (The temporary price rise allowed banks and private mortgage pools to have loans paid off through sales or refinancing, almost all of which was done with government guaranteed loans.) After it ended in the spring of 2010, prices resumed their plunge, especially for homes in the bottom segment of the market.

Price began to turn around in 2013, but adjusting for inflation they were still about even with where they were in 2010. In many areas the prices of more moderate priced homes were still well below their 2010 levels. This would explain why wealth for families near the middle of the income distribution would be below its 2010 level.

That’s not exactly news, but Neil Irwin does a nice job summarizing the data in the Fed’s new Survey of Consumer Finance. The item that many may find surprising is that median wealth was lower in 2013 than it was in 2010 is spite of the boom in the stock market over this period. As Irwin explains, this is due to the fact that most middle income families own little or no stock, even indirectly through mutual funds in retirement accounts.

For people near the middle of the income distribution their wealth is their house. In 2010 house prices were still headed downward. The first-time homebuyers tax credit had temporarily pushed up prices. (The temporary price rise allowed banks and private mortgage pools to have loans paid off through sales or refinancing, almost all of which was done with government guaranteed loans.) After it ended in the spring of 2010, prices resumed their plunge, especially for homes in the bottom segment of the market.

Price began to turn around in 2013, but adjusting for inflation they were still about even with where they were in 2010. In many areas the prices of more moderate priced homes were still well below their 2010 levels. This would explain why wealth for families near the middle of the income distribution would be below its 2010 level.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión