People reading the front page of the NYT yesterday saw the headline, “One Therapist, $4 Million in 2012 Medicare Billing.” That sounds like some pretty serious fraud, since $4 million would be pretty high annual pay for a physical therapist.

Those who read all the way through the piece would find that this was money paid to a therapist who has several offices and claims to employ a total of 24 therapists. This still sounds like a lot of money ($167,000 per therapist), but certainly a very different story than was conveyed by the headline.

Medicare fraud is a really serious problem and the NYT is right to go after it. But this headline seriously misrepresented the nature of the issues in this article. There may well have been improper payments made to this therapist, but there is an enormous difference between what is implied by the headline and likely size of any improper payments, assuming that he did in fact employ 24 therapists.

People reading the front page of the NYT yesterday saw the headline, “One Therapist, $4 Million in 2012 Medicare Billing.” That sounds like some pretty serious fraud, since $4 million would be pretty high annual pay for a physical therapist.

Those who read all the way through the piece would find that this was money paid to a therapist who has several offices and claims to employ a total of 24 therapists. This still sounds like a lot of money ($167,000 per therapist), but certainly a very different story than was conveyed by the headline.

Medicare fraud is a really serious problem and the NYT is right to go after it. But this headline seriously misrepresented the nature of the issues in this article. There may well have been improper payments made to this therapist, but there is an enormous difference between what is implied by the headline and likely size of any improper payments, assuming that he did in fact employ 24 therapists.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

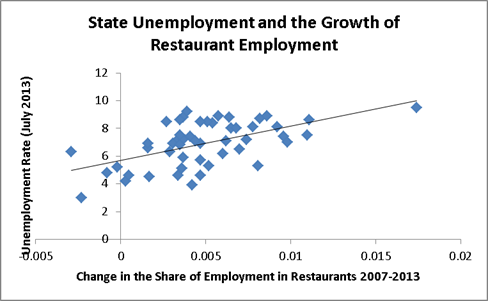

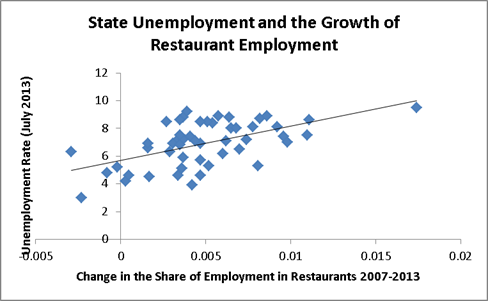

The NYT had an article reporting the large share of job growth that has taken place in low wage industries. This is readily explained by the fact that the economy is not creating many jobs. When the good jobs are available people do not work at low-paying jobs. However Congress and the president have to decided to run fiscal and trade policies that slow growth and limit job creation. As a result many people who would have decent paying jobs in an economy that was near potential GDP instead have to look for work in fast-food restaurants and other low-paying jobs.

This basic point can be seen in the simple correlation of state unemployment rates and the share of new jobs in restaurants as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

In other words, people who are unhappy about bad jobs should be yelling at their political leaders to get over their stupid budget deficit fetish, since we know that we could create lots of good jobs tomorrow by spending more money on infrastructure, education, and other good things. They should also yell at their political leaders to take an intro economics class so that they will realize the trade deficit is costing us more than 5 million jobs. And, the only thing we need to do to get the trade deficit down is to lower the value of the dollar.

Unfortunately the simple facts of economics — straight from any intro textbook — are considered too far out to enter the political debate.

Note: link added.

The NYT had an article reporting the large share of job growth that has taken place in low wage industries. This is readily explained by the fact that the economy is not creating many jobs. When the good jobs are available people do not work at low-paying jobs. However Congress and the president have to decided to run fiscal and trade policies that slow growth and limit job creation. As a result many people who would have decent paying jobs in an economy that was near potential GDP instead have to look for work in fast-food restaurants and other low-paying jobs.

This basic point can be seen in the simple correlation of state unemployment rates and the share of new jobs in restaurants as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

In other words, people who are unhappy about bad jobs should be yelling at their political leaders to get over their stupid budget deficit fetish, since we know that we could create lots of good jobs tomorrow by spending more money on infrastructure, education, and other good things. They should also yell at their political leaders to take an intro economics class so that they will realize the trade deficit is costing us more than 5 million jobs. And, the only thing we need to do to get the trade deficit down is to lower the value of the dollar.

Unfortunately the simple facts of economics — straight from any intro textbook — are considered too far out to enter the political debate.

Note: link added.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an interesting front page article on how efforts to roll back renewable energy requirements are encountering stiff resistance even in heavily Republican states. The resistance is coming largely from businesses who are profiting from producing wind or solar energy. It’s striking that having a relatively small number of businesses who have profits on the line can apparently have a major influence on the political process.

The Washington Post had an interesting front page article on how efforts to roll back renewable energy requirements are encountering stiff resistance even in heavily Republican states. The resistance is coming largely from businesses who are profiting from producing wind or solar energy. It’s striking that having a relatively small number of businesses who have profits on the line can apparently have a major influence on the political process.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Glenn Kessler, the Washington Post’s fact checker, gave the Obama administration two Pinocchios for claiming that 35 percent of the people who enrolled in the exchanges were under age 35. This was close to the administration’s original target of 40 percent for people between the ages of 18-34. Kessler pointed out that the administration was able to get the figure up from a widely reported 28 percent share being between the ages of 18-34 to the 35 percent number by adding children under the age of 18. As Kessler rightly points out, this was deceptive since we should be looking at a different target if we include children. On this basis he awarded the White House two Pinocchios.

There is little grounds for disputing Kessler here, the Obama administration was being deliberately deceptive. The question is the significance of the issue. Kessler says the issue is important because:

“The ‘young invincibles’ are considered a key to the health law’s success, since they are healthier and won’t require as much health care as older Americans. If the proportion of young and old enrollees was out of whack, insurance companies might feel compelled to boost premiums, which some feared would lead to a cycle of even fewer younger adults and higher premiums.”

In fact, the young invincible story is actually mostly wrong. The difference in premiums by age group largely corresponds to the difference in average expenses. An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that even an extreme skewing by age (young people sign up in half of their proportion of the uninsured) would raise costs by less than two percent.

It matters much more for the finances of the system whether there is a skewing by health status than by age. In fact a healthy 60-year old is much more valuable to the system than a healthy 30-year old since they will pay roughly three times the premium. Anyhow, Kessler is right in calling out the White House for its deception on these numbers, however he is wrong about their significance.

Glenn Kessler, the Washington Post’s fact checker, gave the Obama administration two Pinocchios for claiming that 35 percent of the people who enrolled in the exchanges were under age 35. This was close to the administration’s original target of 40 percent for people between the ages of 18-34. Kessler pointed out that the administration was able to get the figure up from a widely reported 28 percent share being between the ages of 18-34 to the 35 percent number by adding children under the age of 18. As Kessler rightly points out, this was deceptive since we should be looking at a different target if we include children. On this basis he awarded the White House two Pinocchios.

There is little grounds for disputing Kessler here, the Obama administration was being deliberately deceptive. The question is the significance of the issue. Kessler says the issue is important because:

“The ‘young invincibles’ are considered a key to the health law’s success, since they are healthier and won’t require as much health care as older Americans. If the proportion of young and old enrollees was out of whack, insurance companies might feel compelled to boost premiums, which some feared would lead to a cycle of even fewer younger adults and higher premiums.”

In fact, the young invincible story is actually mostly wrong. The difference in premiums by age group largely corresponds to the difference in average expenses. An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that even an extreme skewing by age (young people sign up in half of their proportion of the uninsured) would raise costs by less than two percent.

It matters much more for the finances of the system whether there is a skewing by health status than by age. In fact a healthy 60-year old is much more valuable to the system than a healthy 30-year old since they will pay roughly three times the premium. Anyhow, Kessler is right in calling out the White House for its deception on these numbers, however he is wrong about their significance.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Steve Pearlstein argues it is, taking issue with fellow columnist Barry Ritholtz who says it isn’t. I’m going to come down in the middle here.

The market is somewhat above its historic levels relative to trend earnings. Pearlstein cites Shiller who puts the price to earnings ratio at 25 to 1, compared to a historic average of 16. (Pearlstein seems to place a lot of faith in Shiller who he tells us got a Nobel for his knack for spotting bubbles. Shiller may have gotten the Nobel, but I got the bubble story right. In 2003 he argued that there was no bubble in the housing market by making a comparison of real house prices and real incomes. I had recognized the bubble a year earlier by noting that inflation adjusted house prices had been rising since the late 1990s after remaining largely flat for the prior half century. Shiller later did research agreeing with my assessment that quality-adjusted house prices should track inflation, not income.) Anyhow, I would agree that stock prices are somewhat above trend, but not by quite as large a margin as Shiller.

To get some perspective, at the peak of the stock bubble in early 2000, the S&P peaked at just under 1530. The economy is almost than 70 percent larger today (in nominal dollars), which would mean that the S&P would be over 2600 today if it were as high relative to the economy. If we throw in that the economy is still operating at 5 percent below its potential then the S&P would have to be over 2700 now to be as high relative to the economy as it was at the peak of the stock bubble. With a Friday close of 1863, we can see the market is at a level that is a bit more than two thirds of its 2000 bubble peak, relative to the size of the economy.

It also is much lower relative to the economy than it was in 2007 when almost no one was talking about a stock bubble. The S&P peaked at just over 1560 in the fall of 2007. Taking into account the economy’s 18 percent nominal growth over this period, and the fact that we are still 5 percent below potential GDP, the S&P would have to be over 1900 today to be as high relative to potential GDP as it was in 2007. Given recent patterns, it certainly doesn’t make sense to talk about a bubble for the market as a whole.

However, there are some points worth noting. The social media craze has allowed many companies with no profits and few prospects for making profits to market valuations in the hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. That sure looks like the Internet bubble. Some of these companies may end up being profitable and worth something like their current share price. The vast majority probably will not.

The other point is that the higher than trend price to earnings ratio means that we should expect to see lower than trend real returns going forward. This is an important qualification to Ritholtz’s analysis. While there is no reason that people should fear that stocks in general will take a tumble, as they did in 2000-2002, they also would be nuts to expect the same real returns going forward as they saw in the past.

With a price to earnings ratio that is roughly one-third above the long-term trend, they should expect real returns that are roughly one-third lower than the historic average. This means that instead of expecting real returns on stock of 7.0 percent, they should expect something closer to 5.0 percent. That might still make stocks a good investment, especially in the low interest rate environment we see today, but probably not as good as many people are banking on.

In short, there is not much basis for Pearlstein’s bubble story, but we should also expect that because of higher than trend PE ratios stocks will not provide the same returns in the future as they did in the past. Anyone who thinks we can better have their calculator checked.

Washington Post columnist Steve Pearlstein argues it is, taking issue with fellow columnist Barry Ritholtz who says it isn’t. I’m going to come down in the middle here.

The market is somewhat above its historic levels relative to trend earnings. Pearlstein cites Shiller who puts the price to earnings ratio at 25 to 1, compared to a historic average of 16. (Pearlstein seems to place a lot of faith in Shiller who he tells us got a Nobel for his knack for spotting bubbles. Shiller may have gotten the Nobel, but I got the bubble story right. In 2003 he argued that there was no bubble in the housing market by making a comparison of real house prices and real incomes. I had recognized the bubble a year earlier by noting that inflation adjusted house prices had been rising since the late 1990s after remaining largely flat for the prior half century. Shiller later did research agreeing with my assessment that quality-adjusted house prices should track inflation, not income.) Anyhow, I would agree that stock prices are somewhat above trend, but not by quite as large a margin as Shiller.

To get some perspective, at the peak of the stock bubble in early 2000, the S&P peaked at just under 1530. The economy is almost than 70 percent larger today (in nominal dollars), which would mean that the S&P would be over 2600 today if it were as high relative to the economy. If we throw in that the economy is still operating at 5 percent below its potential then the S&P would have to be over 2700 now to be as high relative to the economy as it was at the peak of the stock bubble. With a Friday close of 1863, we can see the market is at a level that is a bit more than two thirds of its 2000 bubble peak, relative to the size of the economy.

It also is much lower relative to the economy than it was in 2007 when almost no one was talking about a stock bubble. The S&P peaked at just over 1560 in the fall of 2007. Taking into account the economy’s 18 percent nominal growth over this period, and the fact that we are still 5 percent below potential GDP, the S&P would have to be over 1900 today to be as high relative to potential GDP as it was in 2007. Given recent patterns, it certainly doesn’t make sense to talk about a bubble for the market as a whole.

However, there are some points worth noting. The social media craze has allowed many companies with no profits and few prospects for making profits to market valuations in the hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. That sure looks like the Internet bubble. Some of these companies may end up being profitable and worth something like their current share price. The vast majority probably will not.

The other point is that the higher than trend price to earnings ratio means that we should expect to see lower than trend real returns going forward. This is an important qualification to Ritholtz’s analysis. While there is no reason that people should fear that stocks in general will take a tumble, as they did in 2000-2002, they also would be nuts to expect the same real returns going forward as they saw in the past.

With a price to earnings ratio that is roughly one-third above the long-term trend, they should expect real returns that are roughly one-third lower than the historic average. This means that instead of expecting real returns on stock of 7.0 percent, they should expect something closer to 5.0 percent. That might still make stocks a good investment, especially in the low interest rate environment we see today, but probably not as good as many people are banking on.

In short, there is not much basis for Pearlstein’s bubble story, but we should also expect that because of higher than trend PE ratios stocks will not provide the same returns in the future as they did in the past. Anyone who thinks we can better have their calculator checked.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Joe Nocera documents what many of us already knew, the multi-million dollar pay packages of corporate CEOs are a matter between friends, not a market relationship. The specific context is the pay of the CEO and other top executives at Coca Cola.

The company has recently been in the news since an activist investor calculated it had set aside $24 billion for management bonuses over a two-year period. An amount that came to $2 million for each person in the pool. Nocera focused on the reaction of Warren Buffett to this news. As a result of his control over Berkshire Hathaway, Buffet is effectively one of the company’s largest shareholders. Buffett has repeatedly complained publicly about outlandish CEO pay packages.

For this reason it seemed reasonable to expect that Buffett would use his shares to vote no when the pay package for Coke’s top executive was put to a vote. However Nocera reports that he chose to abstain. Buffett’s rationale, as relayed through third parties, is that it would have been too confrontational to vote down the package. Essentially Buffett said that he thought the pay was too high, but that he didn’t want to make waves. He also acknowledged supporting other pay packages as a director that he felt were too high in order not to make waves.

This beautifully illustrates the dynamics of CEO pay. This is not a market relationship, it is a deal between friends.

When it comes to the pay of ordinary workers, whether clerks in a Walmart or factory workers in the auto industry, the question is always whether the company can get away with paying less. If lower pay means lobbying against minimum wage hikes or shipping work overseas, it will be done in a second, no apologies made. The story is that the goal is to maximize profits.

Yet, the same corporate board members who tell us about representing shareholders’ when it comes to the pay of ordinary workers, somehow get all touchy feely when it comes to the pay of CEOs and other top management. This was the reason that CEPR started Director Watch and worked with Huffington Post on its Pay Pals site.

The corporate directors are the ones who most immediately need to be harassed. These are mostly prominent public figures (our list of directors profiled to date includes Erskine Bowles, Richard M. Daley, Elaine Chou, and Judith Rodin). They are paid six figure salaries to go to a small number of meetings a year. Their main responsibility is to ensure that management is acting on behalf of the shareholders.

When directors approve exorbitant pay packages even for mediocre CEOs, they cannot claim they are doing their jobs. They are essentially getting paid off to look the other way.

Note: Typos corrected.

Joe Nocera documents what many of us already knew, the multi-million dollar pay packages of corporate CEOs are a matter between friends, not a market relationship. The specific context is the pay of the CEO and other top executives at Coca Cola.

The company has recently been in the news since an activist investor calculated it had set aside $24 billion for management bonuses over a two-year period. An amount that came to $2 million for each person in the pool. Nocera focused on the reaction of Warren Buffett to this news. As a result of his control over Berkshire Hathaway, Buffet is effectively one of the company’s largest shareholders. Buffett has repeatedly complained publicly about outlandish CEO pay packages.

For this reason it seemed reasonable to expect that Buffett would use his shares to vote no when the pay package for Coke’s top executive was put to a vote. However Nocera reports that he chose to abstain. Buffett’s rationale, as relayed through third parties, is that it would have been too confrontational to vote down the package. Essentially Buffett said that he thought the pay was too high, but that he didn’t want to make waves. He also acknowledged supporting other pay packages as a director that he felt were too high in order not to make waves.

This beautifully illustrates the dynamics of CEO pay. This is not a market relationship, it is a deal between friends.

When it comes to the pay of ordinary workers, whether clerks in a Walmart or factory workers in the auto industry, the question is always whether the company can get away with paying less. If lower pay means lobbying against minimum wage hikes or shipping work overseas, it will be done in a second, no apologies made. The story is that the goal is to maximize profits.

Yet, the same corporate board members who tell us about representing shareholders’ when it comes to the pay of ordinary workers, somehow get all touchy feely when it comes to the pay of CEOs and other top management. This was the reason that CEPR started Director Watch and worked with Huffington Post on its Pay Pals site.

The corporate directors are the ones who most immediately need to be harassed. These are mostly prominent public figures (our list of directors profiled to date includes Erskine Bowles, Richard M. Daley, Elaine Chou, and Judith Rodin). They are paid six figure salaries to go to a small number of meetings a year. Their main responsibility is to ensure that management is acting on behalf of the shareholders.

When directors approve exorbitant pay packages even for mediocre CEOs, they cannot claim they are doing their jobs. They are essentially getting paid off to look the other way.

Note: Typos corrected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times ran a piece reporting that more Democrats running for election this year are openly campaigning on the Affordable Care Act. The piece noted that eight million people had signed up for the exchanges by the end of the open enrollment period. While this is a large base of people who may perceive themselves as benefiting from the law, it is worth noting that this number is likely to increase substantially in the months leading up to the election.

Under the law, people who face a “life event” become eligible for insurance in the exchange. Life events include job loss, divorce, death in the family, and the birth of a new child. Every month roughly four million people leave their jobs. If just one in five of these people go from a job with insurance to either being unemployed or a job without insurance, it would mean another 800,000 people are becoming eligible for the exchanges every month for this reason alone.

This means that the number of people who will have had the opportunity to buy insurance through the exchanges by election will be far higher than the number currently enrolled. Since many of these people will have found themselves unexpectedly without insurance, they are likely to especially value the opportunity to buy insurance on the exchanges.

The New York Times ran a piece reporting that more Democrats running for election this year are openly campaigning on the Affordable Care Act. The piece noted that eight million people had signed up for the exchanges by the end of the open enrollment period. While this is a large base of people who may perceive themselves as benefiting from the law, it is worth noting that this number is likely to increase substantially in the months leading up to the election.

Under the law, people who face a “life event” become eligible for insurance in the exchange. Life events include job loss, divorce, death in the family, and the birth of a new child. Every month roughly four million people leave their jobs. If just one in five of these people go from a job with insurance to either being unemployed or a job without insurance, it would mean another 800,000 people are becoming eligible for the exchanges every month for this reason alone.

This means that the number of people who will have had the opportunity to buy insurance through the exchanges by election will be far higher than the number currently enrolled. Since many of these people will have found themselves unexpectedly without insurance, they are likely to especially value the opportunity to buy insurance on the exchanges.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In her Washington Post column Catherine Rampell correctly pointed out that the median return in higher wages for those with college degrees more than covers the tuition and opportunity cost associated with attending college. She notes however that college enrollment has edged downward in recent years.

While she sees this decline largely as the result of young people failing to recognize the benefits of college, it can be more readily explained by a growing divergence in the income of college grads. Work by my colleague John Schmitt and Heather Boushey shows that a substantial proportion of college grads, especially male college grads, earn less than the average high school grad. They found that the lowest earning quintile of recent college grads (ages 25-34) earned less than the average high school grad. The implication is that many young people may be reasonably assessing their risks of not being a winner among college grads and therefore opting not to get additional education. To get more young people to attend college it is important that most can predictably benefit from the additional education, not just that the average pay of college grads rises. (of course the story would be worse for those who start college and do not finish.)

Note: typos were corrected and the comparison was clarified.

In her Washington Post column Catherine Rampell correctly pointed out that the median return in higher wages for those with college degrees more than covers the tuition and opportunity cost associated with attending college. She notes however that college enrollment has edged downward in recent years.

While she sees this decline largely as the result of young people failing to recognize the benefits of college, it can be more readily explained by a growing divergence in the income of college grads. Work by my colleague John Schmitt and Heather Boushey shows that a substantial proportion of college grads, especially male college grads, earn less than the average high school grad. They found that the lowest earning quintile of recent college grads (ages 25-34) earned less than the average high school grad. The implication is that many young people may be reasonably assessing their risks of not being a winner among college grads and therefore opting not to get additional education. To get more young people to attend college it is important that most can predictably benefit from the additional education, not just that the average pay of college grads rises. (of course the story would be worse for those who start college and do not finish.)

Note: typos were corrected and the comparison was clarified.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión