Everyone thought David Brooks was a conservative. But in today’s column on high frequency trading and the fact that it has often been used to support front-running in which traders effectively engage in inside trading, Brooks tells readers:

“You can’t tame the desire for money with sermons. You can only counteract greed with some superior love, like the love of knowledge.

“Third, if market-rigging is defeated, it won’t be by government regulators. It will be through a market innovation”

So there you have it. According to Brooks, if people are stealing on Wall Street we shouldn’t look to try to have regulations and punishment, we should go after them with love. It will be interesting to see if Brooks shows the same attitude towards people’s whose greed leads them to steal cars or burglarize houses.

Everyone thought David Brooks was a conservative. But in today’s column on high frequency trading and the fact that it has often been used to support front-running in which traders effectively engage in inside trading, Brooks tells readers:

“You can’t tame the desire for money with sermons. You can only counteract greed with some superior love, like the love of knowledge.

“Third, if market-rigging is defeated, it won’t be by government regulators. It will be through a market innovation”

So there you have it. According to Brooks, if people are stealing on Wall Street we shouldn’t look to try to have regulations and punishment, we should go after them with love. It will be interesting to see if Brooks shows the same attitude towards people’s whose greed leads them to steal cars or burglarize houses.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Catherine Rampell used her column today to defend an earlier column complaining that baby boomers are taking from young people through Social Security and Medicare. She acknowledges that most baby boomers will not come out ahead on Social Security (actually they come out somewhat behind in the source she cites) but then tells readers:

“Medicare, on the other hand, is pretty much a steal no matter when you turned 65.”

This is true, but it’s hard to argue that it is the beneficiaries who are doing the stealing. We pay more than twice as much per person on average for our health care as people in other wealthy countries. We have little or nothing to show for this extra spending in terms of outcomes. For example, every other wealthy country has longer life expectancies than we do. It therefore is hard to argue that seniors are the beneficiaries of the exorbitant spending on Medicare.

On the other hand, we know who does benefit. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released data this week showing that a small number of doctors account for a grossly disproportionate share of Medicare’s payments to doctors, with many collecting more than $1 million a year from the system. The top earner, a big campaign contributor, pocketed more than $20 million in a single year.

Doctors in the United States earn more than twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. We also pay more than twice as much for our prescription drugs and for medical equipment. If one were to look for people stealing from Medicare, these and other health care providers would be the obvious candidates.

It is also worth noting that the well-being of people of Rampell’s generation (her explicit concern in the piece) will depend far more on stopping and reversing the pattern of upward redistribution of income that we have been seeing since 1980. If this is not reversed then millennials will see little of the 50 percent growth in real compensation over the next three decades that is projected by the Social Security trustees. If millennials are able to secure wage gains that track the economy’s productivity growth then their gains in compensation will be an order of magnitude larger than any possible tax increases associated with Social Security and Medicare.

Catherine Rampell used her column today to defend an earlier column complaining that baby boomers are taking from young people through Social Security and Medicare. She acknowledges that most baby boomers will not come out ahead on Social Security (actually they come out somewhat behind in the source she cites) but then tells readers:

“Medicare, on the other hand, is pretty much a steal no matter when you turned 65.”

This is true, but it’s hard to argue that it is the beneficiaries who are doing the stealing. We pay more than twice as much per person on average for our health care as people in other wealthy countries. We have little or nothing to show for this extra spending in terms of outcomes. For example, every other wealthy country has longer life expectancies than we do. It therefore is hard to argue that seniors are the beneficiaries of the exorbitant spending on Medicare.

On the other hand, we know who does benefit. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released data this week showing that a small number of doctors account for a grossly disproportionate share of Medicare’s payments to doctors, with many collecting more than $1 million a year from the system. The top earner, a big campaign contributor, pocketed more than $20 million in a single year.

Doctors in the United States earn more than twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. We also pay more than twice as much for our prescription drugs and for medical equipment. If one were to look for people stealing from Medicare, these and other health care providers would be the obvious candidates.

It is also worth noting that the well-being of people of Rampell’s generation (her explicit concern in the piece) will depend far more on stopping and reversing the pattern of upward redistribution of income that we have been seeing since 1980. If this is not reversed then millennials will see little of the 50 percent growth in real compensation over the next three decades that is projected by the Social Security trustees. If millennials are able to secure wage gains that track the economy’s productivity growth then their gains in compensation will be an order of magnitude larger than any possible tax increases associated with Social Security and Medicare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The folks on the right don’t seem to think that they should have to be evaluated by the same standards as everyone else. Hence we find George Osborne, the U.K. finance minister, boasting in the WSJ about his country’s economic performance now that its economy is finally beginning to grow again.

For people who missed it, the conservative coalition in the U.K. thought it was smart to cut spending and raise taxes in 2010 even though its economy was very far from full employment. These measures had the effect that fans of economics everywhere predicted, they threw the economy back into recession.

After two and a half years of austerity, the government is reversing course and lo and behold the sun rose this morning the economy is growing again. (Yes, economies do generally grow.) In the wild and wacky world of right-wing economics, this somehow vindicates the conservative policies of the prior two and half years.

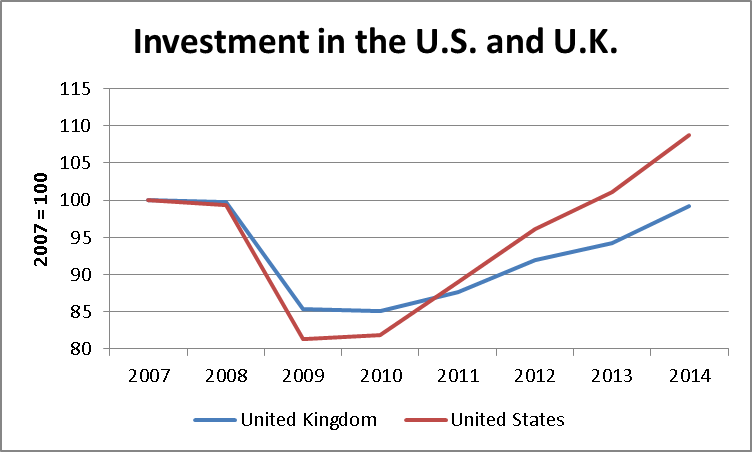

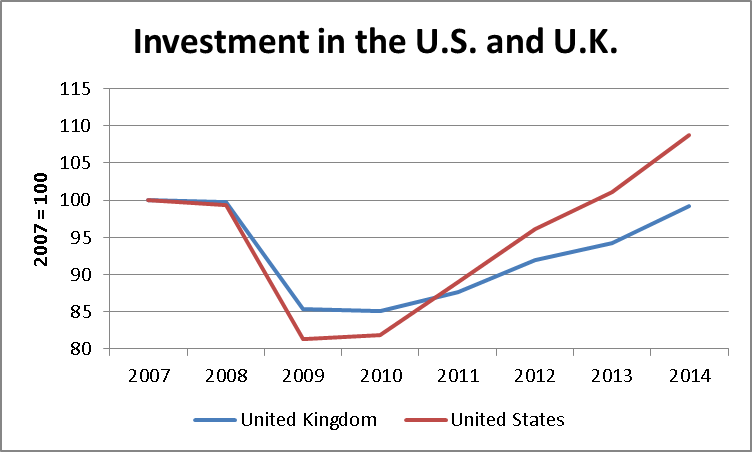

The piece makes many boasts that properly deserve ridicule, but I will just pick my favorite. Here’s Osborne on investment in the U.K.:

“Investment spending has grown by 8.8% over the past year, compared with 2.2% in the U.S. That bodes well for U.K. productivity.”

That’s impressive, in 2013 investment growth in the U.K. was far higher than in the U.S. But suppose we don’t look at one year in isolation but instead look at the whole period since the downturn began. Here’s the story.

Source: OECD.

The figure shows us that when investment was growing at a a near double digit pace in the United States in 2011 and 2012, it was just inching upward under Osborne’s austerity policies in the U.K. It picks up slightly in 2013, but even including the OECD’s growth forecast for 2014, investment in the U.K. is still projected to be below its pre-recession level. By contrast, it will be almost 10 percent above its pre-recession level in the United States.

The U.K. performance would not be the sort of thing that you would generally boast about, but given the affirmative action policies for conservatives at the WSJ and elsewhere in the media, apparently Osborne expects to get away with it.

Note — typos correctd, thanks to Robert Salzberg and CE.

The folks on the right don’t seem to think that they should have to be evaluated by the same standards as everyone else. Hence we find George Osborne, the U.K. finance minister, boasting in the WSJ about his country’s economic performance now that its economy is finally beginning to grow again.

For people who missed it, the conservative coalition in the U.K. thought it was smart to cut spending and raise taxes in 2010 even though its economy was very far from full employment. These measures had the effect that fans of economics everywhere predicted, they threw the economy back into recession.

After two and a half years of austerity, the government is reversing course and lo and behold the sun rose this morning the economy is growing again. (Yes, economies do generally grow.) In the wild and wacky world of right-wing economics, this somehow vindicates the conservative policies of the prior two and half years.

The piece makes many boasts that properly deserve ridicule, but I will just pick my favorite. Here’s Osborne on investment in the U.K.:

“Investment spending has grown by 8.8% over the past year, compared with 2.2% in the U.S. That bodes well for U.K. productivity.”

That’s impressive, in 2013 investment growth in the U.K. was far higher than in the U.S. But suppose we don’t look at one year in isolation but instead look at the whole period since the downturn began. Here’s the story.

Source: OECD.

The figure shows us that when investment was growing at a a near double digit pace in the United States in 2011 and 2012, it was just inching upward under Osborne’s austerity policies in the U.K. It picks up slightly in 2013, but even including the OECD’s growth forecast for 2014, investment in the U.K. is still projected to be below its pre-recession level. By contrast, it will be almost 10 percent above its pre-recession level in the United States.

The U.K. performance would not be the sort of thing that you would generally boast about, but given the affirmative action policies for conservatives at the WSJ and elsewhere in the media, apparently Osborne expects to get away with it.

Note — typos correctd, thanks to Robert Salzberg and CE.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Glenn Kessler, the Washington Post fact checker, gave President Obama two Pinocchios for saying that women earn on average just 77 cents for every dollar that men earn. Kessler makes some valid points as to why this number overstates the gap. First it is an annual number that doesn’t take account of the fact that women are more likely to work part-time and part-year. It is also true that women typically have less work experience because they take time out of the paid labor force.

These and other factors (some of which go in the other direction) would be important items to take into account in a full examination of gender inequality. But has President Obama really committed a two-Pinocchio offense by using a number straight out of Census data without these additional qualifications?

Context is always great, but unfortunately President Obama’s use of the Census pay gap number hardly stands out as an out of context statement by a politician. My favorite in that category was the $1 million spent on a museum of the Woodstock music festival that Senator McCain used as one of his main props in his 2008 presidential campaign. Does anyone think McCain’s complaint about government waste and excesses would have packed the same punch if he told audiences the government had spent 0.00003 percent of its budget on a Woodstock museum? (On this score, why do the Post and other newspapers continue to express budget items exclusively in billions and trillions of dollars when everyone knows these numbers are meaningless to almost their entire readership?)

Unfortunately, making comparisons that don’t convey the full context is a practice that extends beyond politics into the policy world. A couple of years ago, Pew Research Center issued a widely cited study that purported to show growing disparities in wealth between the old and the young over the last quarter century. The study neglected to mention the fact that one of the main contributors to the growth in an age related wealth gap was a switch from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions and the rapid disappearance of retiree health insurance.

In the Pew analysis, a defined benefit pension plan (which most middle class workers would have had in 1984, the base year for the analysis) does not count as wealth, while a defined contribution plan does. Also, workers with retiree health benefits would need to save less to provide for their health care expenses in retirement. These benefits also would have been a form of uncounted wealth in 1984 that would have been available to most middle class workers.

Wealth is also a dubious measure of the well-being of young people. A 30-year old Harvard MBA who has negative net wealth of $150,000 due to student loan debt should not be considered to be in difficult economic straights. What will determine the well-being of young people is the state of the labor market they will face over their working career, whether they have $10,000 more or less in assets by the time they are age 35 will be barely noticeable in comparison.

Anyhow, if we applied the Kessler Pinocchio standard to this Pew study, it would likely score at least a three, if not a four. It is unfortunate that we routinely have facts and numbers given to us out of context, but President Obama, in using standard Census data in referring to the gender pay gap, hardly ranks as one of the bigger offenders in this town.

Glenn Kessler, the Washington Post fact checker, gave President Obama two Pinocchios for saying that women earn on average just 77 cents for every dollar that men earn. Kessler makes some valid points as to why this number overstates the gap. First it is an annual number that doesn’t take account of the fact that women are more likely to work part-time and part-year. It is also true that women typically have less work experience because they take time out of the paid labor force.

These and other factors (some of which go in the other direction) would be important items to take into account in a full examination of gender inequality. But has President Obama really committed a two-Pinocchio offense by using a number straight out of Census data without these additional qualifications?

Context is always great, but unfortunately President Obama’s use of the Census pay gap number hardly stands out as an out of context statement by a politician. My favorite in that category was the $1 million spent on a museum of the Woodstock music festival that Senator McCain used as one of his main props in his 2008 presidential campaign. Does anyone think McCain’s complaint about government waste and excesses would have packed the same punch if he told audiences the government had spent 0.00003 percent of its budget on a Woodstock museum? (On this score, why do the Post and other newspapers continue to express budget items exclusively in billions and trillions of dollars when everyone knows these numbers are meaningless to almost their entire readership?)

Unfortunately, making comparisons that don’t convey the full context is a practice that extends beyond politics into the policy world. A couple of years ago, Pew Research Center issued a widely cited study that purported to show growing disparities in wealth between the old and the young over the last quarter century. The study neglected to mention the fact that one of the main contributors to the growth in an age related wealth gap was a switch from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions and the rapid disappearance of retiree health insurance.

In the Pew analysis, a defined benefit pension plan (which most middle class workers would have had in 1984, the base year for the analysis) does not count as wealth, while a defined contribution plan does. Also, workers with retiree health benefits would need to save less to provide for their health care expenses in retirement. These benefits also would have been a form of uncounted wealth in 1984 that would have been available to most middle class workers.

Wealth is also a dubious measure of the well-being of young people. A 30-year old Harvard MBA who has negative net wealth of $150,000 due to student loan debt should not be considered to be in difficult economic straights. What will determine the well-being of young people is the state of the labor market they will face over their working career, whether they have $10,000 more or less in assets by the time they are age 35 will be barely noticeable in comparison.

Anyhow, if we applied the Kessler Pinocchio standard to this Pew study, it would likely score at least a three, if not a four. It is unfortunate that we routinely have facts and numbers given to us out of context, but President Obama, in using standard Census data in referring to the gender pay gap, hardly ranks as one of the bigger offenders in this town.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Casey Mulligan has once again left me baffled by the economic analysis in his Economix blogpost. If I’m understanding him correctly he is saying that the deductibles for insurance provided through the exchanges in 2015 should be allowed to rise by 40 percent, based on a rise of this amount in the average premium of non-employer provided insurance policies in 2014 compared with 2013. This is based on the provision of the law that deductibles and other adjustable payments should rise in step with medical inflation.

However as Mulligan points out at length, the 40 percent rise in the cost of the average premium in 2014 was not due to medical inflation but rather due to the fact that policies being issued in 2014 under the provisions of the ACA were more comprehensive than the policies being issued in 2013. Since the insurers priced these benefits into the premiums they charged in 2014, and this was also priced into the original schedule of deductibles and subsidies, why would we expect these costs to rise by 40 percent in 2015 relative to 2014.

Based on this logic, the Department of Health and Human Services has set the target increase for a variety of indexed measures in the ACA at 4.2 percent, its calculation of the overall rate of increase in per capita health care costs. It’s not clear where Mulligan sees a problem here. Perhaps he is a better lawyer than me and believes the law requires that these targted payments in future years should rise based on the one time increase in 2014, but it is certainly hard to see any economic logic behind this view. In other words, if there is a scandal in having the targeted payments in the ACA rise in step with health care costs, it’s hard to see what it is.

Addendum: An earlier version wrongly said that Mullligan was referring to insurance prices.

Casey Mulligan has once again left me baffled by the economic analysis in his Economix blogpost. If I’m understanding him correctly he is saying that the deductibles for insurance provided through the exchanges in 2015 should be allowed to rise by 40 percent, based on a rise of this amount in the average premium of non-employer provided insurance policies in 2014 compared with 2013. This is based on the provision of the law that deductibles and other adjustable payments should rise in step with medical inflation.

However as Mulligan points out at length, the 40 percent rise in the cost of the average premium in 2014 was not due to medical inflation but rather due to the fact that policies being issued in 2014 under the provisions of the ACA were more comprehensive than the policies being issued in 2013. Since the insurers priced these benefits into the premiums they charged in 2014, and this was also priced into the original schedule of deductibles and subsidies, why would we expect these costs to rise by 40 percent in 2015 relative to 2014.

Based on this logic, the Department of Health and Human Services has set the target increase for a variety of indexed measures in the ACA at 4.2 percent, its calculation of the overall rate of increase in per capita health care costs. It’s not clear where Mulligan sees a problem here. Perhaps he is a better lawyer than me and believes the law requires that these targted payments in future years should rise based on the one time increase in 2014, but it is certainly hard to see any economic logic behind this view. In other words, if there is a scandal in having the targeted payments in the ACA rise in step with health care costs, it’s hard to see what it is.

Addendum: An earlier version wrongly said that Mullligan was referring to insurance prices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Krugman continues to delve into the depths of sustained secular stagnation asking about the possibility of a prolonged period where the economy does not self-correct to full employment. In the process he takes a sidestep to tell readers that this is not the secular stagnation story of Bill Greider from the 1990s. This one is worth a moment’s thought. (Just to be clear, I consider both Krugman and Greider friends, so I don’t have a particular ax to grind in this story.)

Greider hit on a number of themes in this book, but at least part of the story was one of the U.S. trade deficit creating a deficiency in aggregate demand. In properly behaved macro models, trade deficits are supposed to be self-correcting as the value of the deficit nation’s currency falls and the values of the surplus nations’ currencies rise. This makes imports more expensive to the deficit nation and their exports cheaper to people living in other countries. This leads to fewer imports and more exports and therefore more balanced trade.

But this adjustment has not happened, or certainly has not happened quickly. We can blame evil doers at central banks in other countries who are manipulating their currencies or frightened foreigner investors who think dollar denominated assets are the only safe place to store their wealth. The actual cause does not matter, the point is that the dollar has not fallen to correct the imbalance.

As a result, the trade deficit continued to expand through the late 1990s and into the last decade, eventually peaking at almost 6.0 percent of GDP in 2005. It has fallen back somewhat due to the drop in the value of the dollar, decreased energy imports, and the continuing weakness of the economy reducing the demand for imports. However it is still close to 3.0 percent of GDP. Applying a multiplier of 1.5 this implies a loss of demand equal to 4.5 percent of GDP, or close to $700 billion a year in today’s economy.

It is worth comparing the size of this demand loss with the amount that can be plausibly attributed to productivity and labor force growth slowdown in Krugman’s secular stagnation story. In that story, we are seeing lower investment than if productivity and labor force growth had continued on their prior track. But how large could that effect plausibly be? Would investment be three percentage points higher as a share of GDP if productivity and the labor force had continued on their prior pace? That would put the investment share above the peak it hit during the dot.com bubble and the Y2K scare. That doesn’t seem like a very plausible counter-factual.

In other words, it seems that the trade deficit has to be pretty central in any serious story of long-term secular stagnation, at least as applies to the United States. It has been and is a very big deal.

(As an aside, Krugman asks if we can deal with sustained secular stagnation by running ever larger government deficits. If we are destined to be forever below potential GDP, it’s hard to see why not. Aftar all, it’s not as though there is any reason to believe that printing the money to finance the deficits would create inflation.)

Paul Krugman continues to delve into the depths of sustained secular stagnation asking about the possibility of a prolonged period where the economy does not self-correct to full employment. In the process he takes a sidestep to tell readers that this is not the secular stagnation story of Bill Greider from the 1990s. This one is worth a moment’s thought. (Just to be clear, I consider both Krugman and Greider friends, so I don’t have a particular ax to grind in this story.)

Greider hit on a number of themes in this book, but at least part of the story was one of the U.S. trade deficit creating a deficiency in aggregate demand. In properly behaved macro models, trade deficits are supposed to be self-correcting as the value of the deficit nation’s currency falls and the values of the surplus nations’ currencies rise. This makes imports more expensive to the deficit nation and their exports cheaper to people living in other countries. This leads to fewer imports and more exports and therefore more balanced trade.

But this adjustment has not happened, or certainly has not happened quickly. We can blame evil doers at central banks in other countries who are manipulating their currencies or frightened foreigner investors who think dollar denominated assets are the only safe place to store their wealth. The actual cause does not matter, the point is that the dollar has not fallen to correct the imbalance.

As a result, the trade deficit continued to expand through the late 1990s and into the last decade, eventually peaking at almost 6.0 percent of GDP in 2005. It has fallen back somewhat due to the drop in the value of the dollar, decreased energy imports, and the continuing weakness of the economy reducing the demand for imports. However it is still close to 3.0 percent of GDP. Applying a multiplier of 1.5 this implies a loss of demand equal to 4.5 percent of GDP, or close to $700 billion a year in today’s economy.

It is worth comparing the size of this demand loss with the amount that can be plausibly attributed to productivity and labor force growth slowdown in Krugman’s secular stagnation story. In that story, we are seeing lower investment than if productivity and labor force growth had continued on their prior track. But how large could that effect plausibly be? Would investment be three percentage points higher as a share of GDP if productivity and the labor force had continued on their prior pace? That would put the investment share above the peak it hit during the dot.com bubble and the Y2K scare. That doesn’t seem like a very plausible counter-factual.

In other words, it seems that the trade deficit has to be pretty central in any serious story of long-term secular stagnation, at least as applies to the United States. It has been and is a very big deal.

(As an aside, Krugman asks if we can deal with sustained secular stagnation by running ever larger government deficits. If we are destined to be forever below potential GDP, it’s hard to see why not. Aftar all, it’s not as though there is any reason to believe that printing the money to finance the deficits would create inflation.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Solman seems determined to make me an optimist on the state of the economy, at least by comparison. Following the comments of Kristin Butcher, chair of Wellesley’s economic department, his blogpost on the March jobs report dismisses the 192,000 job growth reported for March:

“That’s because, according to the survey of 60,000 households, roughly 170,000 more Americans of working age were added to the population in March, consistent with the number we add just about every month, and also consistent with the Census Bureau’s report that the U.S. population is growing at slightly more than 2 million people a year.But that would mean that the number of jobs added — 192,000 — just kept pace with the number of new people who needed them.”

This comment misses the fact that not everyone works. The employment to population ratio (EPOP) is just below 60 percent. This means that for the EPOP to stay constant we need roughly 100,000 new jobs a month. In this context, the March numbers implied that we reduced the number of unemployed by roughly 90,000.

The other item on which I am more optimistic than Solman is part-time employment. He emphasized the rise in involuntary part-time as bad news. I looked to the rise in voluntary part-time as good news. While the number of people working part-time involuntarily did rise in March, it is still 240,000 (@ 3.0 percent) below the year ago level, and is fact well below the level for any month in 2013. These numbers are erratic and the March rise partly reverses a drop of 580,000 reported between December and February. In other words, there is no evidence in this series that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is increasing the number of people involuntarily working part-time as the post suggests.

On the other hand, the number of people who are voluntarily working part-time increased by 230,000 in March and is 515,000 above its year ago level. One possible effect of the ACA would be to give workers the option to work part-time who previously may have had to work full-time to get health care insurance. Since workers can now get insurance through their exchanges rather than their jobs, many may choose to work fewer hours to spend more time with their families or doing other things. This is especially likely for parents of young children.

In short, the data to date would support the view that Obamacare is having a positive effect on the labor market by giving workers more choices. But we will need many more months of data before we can say this with any confidence.

Paul Solman seems determined to make me an optimist on the state of the economy, at least by comparison. Following the comments of Kristin Butcher, chair of Wellesley’s economic department, his blogpost on the March jobs report dismisses the 192,000 job growth reported for March:

“That’s because, according to the survey of 60,000 households, roughly 170,000 more Americans of working age were added to the population in March, consistent with the number we add just about every month, and also consistent with the Census Bureau’s report that the U.S. population is growing at slightly more than 2 million people a year.But that would mean that the number of jobs added — 192,000 — just kept pace with the number of new people who needed them.”

This comment misses the fact that not everyone works. The employment to population ratio (EPOP) is just below 60 percent. This means that for the EPOP to stay constant we need roughly 100,000 new jobs a month. In this context, the March numbers implied that we reduced the number of unemployed by roughly 90,000.

The other item on which I am more optimistic than Solman is part-time employment. He emphasized the rise in involuntary part-time as bad news. I looked to the rise in voluntary part-time as good news. While the number of people working part-time involuntarily did rise in March, it is still 240,000 (@ 3.0 percent) below the year ago level, and is fact well below the level for any month in 2013. These numbers are erratic and the March rise partly reverses a drop of 580,000 reported between December and February. In other words, there is no evidence in this series that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is increasing the number of people involuntarily working part-time as the post suggests.

On the other hand, the number of people who are voluntarily working part-time increased by 230,000 in March and is 515,000 above its year ago level. One possible effect of the ACA would be to give workers the option to work part-time who previously may have had to work full-time to get health care insurance. Since workers can now get insurance through their exchanges rather than their jobs, many may choose to work fewer hours to spend more time with their families or doing other things. This is especially likely for parents of young children.

In short, the data to date would support the view that Obamacare is having a positive effect on the labor market by giving workers more choices. But we will need many more months of data before we can say this with any confidence.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his Washington Post column Michael Gerson told readers that health care costs increased at the fastest rate in 10 years in the last quarter of 2013. His source lists the growth rate of expenditures (not costs) at 5.6 percent in the quarter. This follows very slow growth in the prior three quarters. By comparison, health care spending grew by 6.7 percent over the whole year in 2007. There may well have been quarters more recently in which the growth rate exceeded 5.7 percent (the quarterly data are erratic), but clearly the claim that the fourth quarter growth rate was a ten-year high is obviously not true.

In his Washington Post column Michael Gerson told readers that health care costs increased at the fastest rate in 10 years in the last quarter of 2013. His source lists the growth rate of expenditures (not costs) at 5.6 percent in the quarter. This follows very slow growth in the prior three quarters. By comparison, health care spending grew by 6.7 percent over the whole year in 2007. There may well have been quarters more recently in which the growth rate exceeded 5.7 percent (the quarterly data are erratic), but clearly the claim that the fourth quarter growth rate was a ten-year high is obviously not true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión