The NYT had a piece noting how states across the country are seeing better budget pictures than they had projected. While this is attributed to growth, economic growth in 2013 was pretty much in line with expectations (worse in first half, better in second). The more plausible explanation is that the run-up in the stock market to both more capital gains taxes (a point that is noted) and also for capital gains income in many cases to be reported and taxed as normal income.

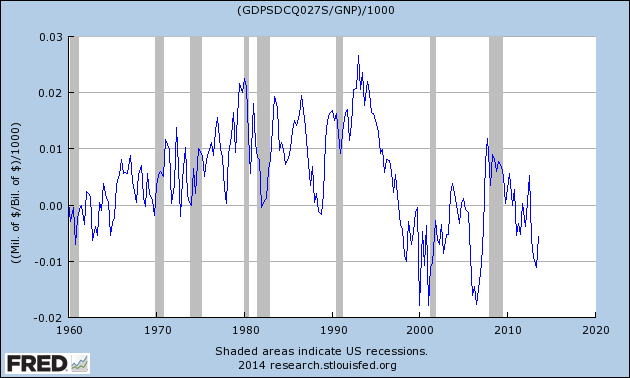

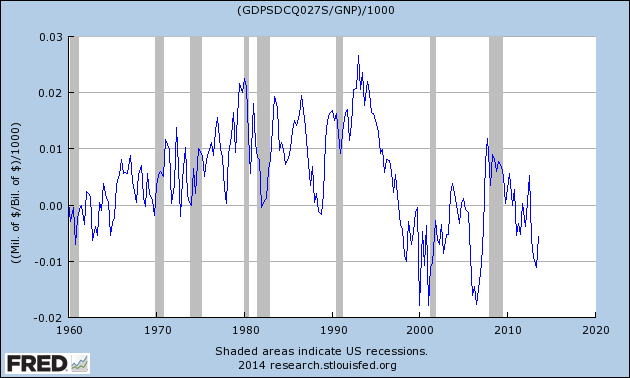

For tax purposes, short-term capital gains (assets held less than a year) are treated the same as normal income. Therefore it is likely that many households just report capital gains earnings as normal income. This would explain why the statistical discrepancy turns negative following large run-ups in asset prices such as the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade.

The implication of this scenario is that much of the increase in the tax revenue that states are now seeing is ephemeral. Unless stock and/or house prices continue to rise at an extraordinary pace, the statistical discrepancy will fall back toward zero and the extra tax revenue states are now seeing will disappear.

The NYT had a piece noting how states across the country are seeing better budget pictures than they had projected. While this is attributed to growth, economic growth in 2013 was pretty much in line with expectations (worse in first half, better in second). The more plausible explanation is that the run-up in the stock market to both more capital gains taxes (a point that is noted) and also for capital gains income in many cases to be reported and taxed as normal income.

For tax purposes, short-term capital gains (assets held less than a year) are treated the same as normal income. Therefore it is likely that many households just report capital gains earnings as normal income. This would explain why the statistical discrepancy turns negative following large run-ups in asset prices such as the stock bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the last decade.

The implication of this scenario is that much of the increase in the tax revenue that states are now seeing is ephemeral. Unless stock and/or house prices continue to rise at an extraordinary pace, the statistical discrepancy will fall back toward zero and the extra tax revenue states are now seeing will disappear.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We’ve been reading stories in the NYT and elsewhere about how Chicago has pension obligations to its workers that it can’t possibly meet. Most of these accounts are exaggerated and seem intended to provoke excessive fears in order to facilitate default on the city’s pension obligations. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that the city has seriously underfunded pensions.

This is why it is striking that when the NYT ran a piece on former Mayor Richard M. Daley going to the hospital, it failed to mention Daley’s record on the city’s pensions, telling readers:

“Mr. Daley, Chicago’s longest-serving mayor with 22 years in office, is credited with giving the city a face lift with new green spaces, a revived theater district and the transformation of Navy Pier into a colorful playground.”

Daley is the person most responsible for the underfunding of Chicago’s pensions, making him one of the most irresponsible elected leaders in recent history. It would be understandable that the NYT may not want to highlight negative aspects of Mr. Daley’s tenure at a moment when he is apparently dealing with serious health issues, but there is no excuse for this sort of whitewashing of his record. Tens of thousands of people who worked for the city for decades may not see the pensions they earned as a result of Daley’s recklessness.

We’ve been reading stories in the NYT and elsewhere about how Chicago has pension obligations to its workers that it can’t possibly meet. Most of these accounts are exaggerated and seem intended to provoke excessive fears in order to facilitate default on the city’s pension obligations. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that the city has seriously underfunded pensions.

This is why it is striking that when the NYT ran a piece on former Mayor Richard M. Daley going to the hospital, it failed to mention Daley’s record on the city’s pensions, telling readers:

“Mr. Daley, Chicago’s longest-serving mayor with 22 years in office, is credited with giving the city a face lift with new green spaces, a revived theater district and the transformation of Navy Pier into a colorful playground.”

Daley is the person most responsible for the underfunding of Chicago’s pensions, making him one of the most irresponsible elected leaders in recent history. It would be understandable that the NYT may not want to highlight negative aspects of Mr. Daley’s tenure at a moment when he is apparently dealing with serious health issues, but there is no excuse for this sort of whitewashing of his record. Tens of thousands of people who worked for the city for decades may not see the pensions they earned as a result of Daley’s recklessness.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has a very good piece about what having health insurance means to poor people in Eastern Kentucky with chronic health care conditions. As a famous vice-president once said, “it’s a big f***ing deal.”

That’s not an excuse to overlook the huge flaws in Obamacare. For many people care will still be unaffordable. And the insurance companies, drug companies, medical supply companies and doctors are still ripping us off. But as this piece shows, it is already having a huge impact on people’s lives.

The Washington Post has a very good piece about what having health insurance means to poor people in Eastern Kentucky with chronic health care conditions. As a famous vice-president once said, “it’s a big f***ing deal.”

That’s not an excuse to overlook the huge flaws in Obamacare. For many people care will still be unaffordable. And the insurance companies, drug companies, medical supply companies and doctors are still ripping us off. But as this piece shows, it is already having a huge impact on people’s lives.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Firms added inventories at a record $127.2 billion (in 2009 dollars) annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2014. This increase did not draw much attention because it was only $11.5 billion above the third quarter pace, adding 0.44 percentage points to GDP growth in the quarter. The extraordinary pace of inventory growth in the last two quarters means it is likely that inventory growth will slow in future quarters, which will be somewhat of a drag on growth.

However, it is worth noting that we are likely looking at a slower rate of inventory growth in future quarters, not actually a decrease in inventories as has been suggested in several reports. If inventories were to actually decline (which they almost never do outside of recessions) then it would be a huge drag on growth almost certainly pushing GDP in negative territory. Just to take a simple case, if inventories stayed flat in the first quarter, then the rate of inventory accumulation would have fallen by $127.2 billion, in a single quarter. This would translate into roughly a $508.8 billion annual rate of change (the quarterly rate multiplied by four). With GDP at roughly $16 trillion (in 2009 dollars), this would knock roughly 3.2 percentage points off the rate of growth in the quarter.

Since the underlying rate of growth is almost certainly less than 3.0 percent at the moment, the flatlining of inventories would push growth into negative territory. Even a modest fall in inventories would virtually guarantee a substantial drop in GDP in the first quarter.

Firms added inventories at a record $127.2 billion (in 2009 dollars) annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2014. This increase did not draw much attention because it was only $11.5 billion above the third quarter pace, adding 0.44 percentage points to GDP growth in the quarter. The extraordinary pace of inventory growth in the last two quarters means it is likely that inventory growth will slow in future quarters, which will be somewhat of a drag on growth.

However, it is worth noting that we are likely looking at a slower rate of inventory growth in future quarters, not actually a decrease in inventories as has been suggested in several reports. If inventories were to actually decline (which they almost never do outside of recessions) then it would be a huge drag on growth almost certainly pushing GDP in negative territory. Just to take a simple case, if inventories stayed flat in the first quarter, then the rate of inventory accumulation would have fallen by $127.2 billion, in a single quarter. This would translate into roughly a $508.8 billion annual rate of change (the quarterly rate multiplied by four). With GDP at roughly $16 trillion (in 2009 dollars), this would knock roughly 3.2 percentage points off the rate of growth in the quarter.

Since the underlying rate of growth is almost certainly less than 3.0 percent at the moment, the flatlining of inventories would push growth into negative territory. Even a modest fall in inventories would virtually guarantee a substantial drop in GDP in the first quarter.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steve Rattner gives us a glowing appraisal of Ben Bernanke on his departure from the Fed. I have written on Bernanke elsewhere, but the basic story is that he bears a large amount of responsibility for the housing bubble and its subsequent bursting, since he was a Fed governor and chief economic advisorin the Bush administration as policymakers allowed it to grow to ever more dangerous levels. The result has been a loss of more than $7.6 trillion in output to date ($25,000 per person) and an economy that is still down more than 8 million jobs six years after the beginning of the downturn. There were few people better positioned than Bernanke to try to stem the growth of the bubble, but he consistently insisted that it did not pose any problem to the economy.

Bernanke also made the decision to leave the financial industry intact at a time when the market would have sent Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and most of the other Wall Street giants into bankruptcy. He misled Congress to rush it into passage of the TARP and he gave hundreds of billions of dollars worth of loan subsidies and guarantees to keep Wall Street alive. As a result, the financial industry is more concentrated than ever.

Bernanke does deserve credit for his aggressive monetary policy in the face of harsh opposition from Republicans and some Democrats. It has boosted the economy, although other banks, notably the Bank of Japan, have been more aggressive. Anyhow, his monetary policy over the last four years certainly is a plus, but it doesn’t qualify Bernanke as a “godsend” by the usual meaning of the word.

Steve Rattner gives us a glowing appraisal of Ben Bernanke on his departure from the Fed. I have written on Bernanke elsewhere, but the basic story is that he bears a large amount of responsibility for the housing bubble and its subsequent bursting, since he was a Fed governor and chief economic advisorin the Bush administration as policymakers allowed it to grow to ever more dangerous levels. The result has been a loss of more than $7.6 trillion in output to date ($25,000 per person) and an economy that is still down more than 8 million jobs six years after the beginning of the downturn. There were few people better positioned than Bernanke to try to stem the growth of the bubble, but he consistently insisted that it did not pose any problem to the economy.

Bernanke also made the decision to leave the financial industry intact at a time when the market would have sent Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and most of the other Wall Street giants into bankruptcy. He misled Congress to rush it into passage of the TARP and he gave hundreds of billions of dollars worth of loan subsidies and guarantees to keep Wall Street alive. As a result, the financial industry is more concentrated than ever.

Bernanke does deserve credit for his aggressive monetary policy in the face of harsh opposition from Republicans and some Democrats. It has boosted the economy, although other banks, notably the Bank of Japan, have been more aggressive. Anyhow, his monetary policy over the last four years certainly is a plus, but it doesn’t qualify Bernanke as a “godsend” by the usual meaning of the word.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There has been a bizarre cult of deflation phobia over the last decade in which we are supposed to be terrified that very low positive rates of inflation can decline further and turn into low rates of deflation, which then create really big problems. The NYT tells us this cult is still dominating economic thinking. In an article on the latest data on inflation and unemployment in the euro zone, it noted that European Central Bank President Mario Draghi unexpectedly lowered interest rates in November:

“amid concern that Europe might be headed toward a Japan-style deflationary quagmire.”

In reality Europe is already in a Japan-style deflationary quagmire. It suffers from an inflation rate that is too low. A higher inflation rate would translate into lower real interest rates, giving firms more incentive to invest. It would also reduce debt burdens for homeowners as the real value of their mortgage debt fell. It would also allow the peripheral countries like Greece, Spain, and Italy to regain competitiveness, if they held wage and price increases below the rates in Germany and other core countries.

For these reasons the near zero inflation rate is making Europe’s problems more difficult, delaying the adjustment process that could allow it to return to a healthy growth path. If the inflation rate were to fall further, say from a positive 0.7 percent to a negative 0.3 percent, this would make matters worse, but only in the same way that a drop in the inflation rate from a positive 1.7 percent to 0.7 percent also makes the situation worse. The issue is a one percentage point decline in the inflation rate, there is no importance to crossing zero.

This should be obvious to people familiar with the construction of price indices. The indexes are based on the collection of millions of different price changes. When the index is near zero, many prices are already falling. Going from a low positive to a low negative rate means that the percentage of falling prices in the index has risen somewhat. How could this possibly have catastrophic consequences for the economy? (In this context it is worth noting that computers and cell phones have had rapidly falling prices for decades. Has everyone noticed the disasters befalling these industries?)

Also, the prices recorded for each item depend on quality adjustments imputed by the statistical agencies. Often the price of a product like a refrigerator or a car might show an increase, but due to imputed quality adjustments it will be recorded as a price decline. Is it plausible that the economy would face some horror story if the pace of quality improvement in these products increases slightly?

The notion that something bad happens if inflation crosses the zero line and becomes deflation is silly on its face. (There is a bad story where the rate of deflation continually accelerates, but even Japan never saw this.) It is often said that economists are not very good at economics. The concerns over a deflation horror story provides a good example of this proposition.

There has been a bizarre cult of deflation phobia over the last decade in which we are supposed to be terrified that very low positive rates of inflation can decline further and turn into low rates of deflation, which then create really big problems. The NYT tells us this cult is still dominating economic thinking. In an article on the latest data on inflation and unemployment in the euro zone, it noted that European Central Bank President Mario Draghi unexpectedly lowered interest rates in November:

“amid concern that Europe might be headed toward a Japan-style deflationary quagmire.”

In reality Europe is already in a Japan-style deflationary quagmire. It suffers from an inflation rate that is too low. A higher inflation rate would translate into lower real interest rates, giving firms more incentive to invest. It would also reduce debt burdens for homeowners as the real value of their mortgage debt fell. It would also allow the peripheral countries like Greece, Spain, and Italy to regain competitiveness, if they held wage and price increases below the rates in Germany and other core countries.

For these reasons the near zero inflation rate is making Europe’s problems more difficult, delaying the adjustment process that could allow it to return to a healthy growth path. If the inflation rate were to fall further, say from a positive 0.7 percent to a negative 0.3 percent, this would make matters worse, but only in the same way that a drop in the inflation rate from a positive 1.7 percent to 0.7 percent also makes the situation worse. The issue is a one percentage point decline in the inflation rate, there is no importance to crossing zero.

This should be obvious to people familiar with the construction of price indices. The indexes are based on the collection of millions of different price changes. When the index is near zero, many prices are already falling. Going from a low positive to a low negative rate means that the percentage of falling prices in the index has risen somewhat. How could this possibly have catastrophic consequences for the economy? (In this context it is worth noting that computers and cell phones have had rapidly falling prices for decades. Has everyone noticed the disasters befalling these industries?)

Also, the prices recorded for each item depend on quality adjustments imputed by the statistical agencies. Often the price of a product like a refrigerator or a car might show an increase, but due to imputed quality adjustments it will be recorded as a price decline. Is it plausible that the economy would face some horror story if the pace of quality improvement in these products increases slightly?

The notion that something bad happens if inflation crosses the zero line and becomes deflation is silly on its face. (There is a bad story where the rate of deflation continually accelerates, but even Japan never saw this.) It is often said that economists are not very good at economics. The concerns over a deflation horror story provides a good example of this proposition.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article discussing the extent to which political unrest in Thailand might have an impact on its economy. At one point it notes a flight of foreign capital from Thailand and other developing countries which it attributes to the Fed’s taper and the “prospect of higher interest rates” in the United States.

The problem with this story is that long-term interest rates have actually been falling in the United States. If investors are fleeing Thailand and other countries because they expect long-term interest rates in the U.S. to rise, then these same investors should be dumping long-term bonds in advance of the interest rate hikes (which would lead to capital losses) thereby causing the rise in interest rates they expect. Instead interest rates on 10-year Treasury bonds have fallen from just over 3.0 percent in late December to under 2.7 percent as of Friday morning.

This suggests an alternative explanation for the flight from developing countries. Most likely it is a simple story of contagion, where investors feel the need to do whatever they see other investors doing. In prior years it was fashionable to unthinkingly put money into developing countries. Now that fashions have shifted the cool thing to do is to pull money out of developing countries. Since investors rarely get in trouble for making the same stupid mistake as everyone else, there is a big incentive to follow fashions in investing.

The NYT had an article discussing the extent to which political unrest in Thailand might have an impact on its economy. At one point it notes a flight of foreign capital from Thailand and other developing countries which it attributes to the Fed’s taper and the “prospect of higher interest rates” in the United States.

The problem with this story is that long-term interest rates have actually been falling in the United States. If investors are fleeing Thailand and other countries because they expect long-term interest rates in the U.S. to rise, then these same investors should be dumping long-term bonds in advance of the interest rate hikes (which would lead to capital losses) thereby causing the rise in interest rates they expect. Instead interest rates on 10-year Treasury bonds have fallen from just over 3.0 percent in late December to under 2.7 percent as of Friday morning.

This suggests an alternative explanation for the flight from developing countries. Most likely it is a simple story of contagion, where investors feel the need to do whatever they see other investors doing. In prior years it was fashionable to unthinkingly put money into developing countries. Now that fashions have shifted the cool thing to do is to pull money out of developing countries. Since investors rarely get in trouble for making the same stupid mistake as everyone else, there is a big incentive to follow fashions in investing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson is happy to tell us that contrary to what he hoped some of us believed, there was not much change in mobility for children entering the labor force between the first President Bush and second President Bush’s administrations. Samuelson misrepresents the study to imply that it finds that there has been no change in mobility over the post-war period.

“By the conventional wisdom, American society is becoming more rigid. People’s place on the economic ladder (“relative mobility”) is increasingly fixed.

“Untrue, concludes the NBER study.”

Samuelson then notes the study’s finding that there has been little change in mobility for workers entering the labor market in 2007 compared to 1990. The study then refers to earlier work finding no change in mobility prior to 1990. This study did not itself examine the period prior to 1990.

This is important since that is the period in which we might have expected growing inequality to have a notable impact on mobility. There was some divergence between quintiles of income distribution in the 1980s. In the years since 1980, there has not been much divergence between the bottom half of the top quintile and the rest of the income distribution. Most of the inequality was associated with the pulling away of the one percent from everyone else. This study made no effort to examine mobility into the one percent.

As far as mobility in the years prior to the 1990, contrary to the claim of this study, the research is far from conclusive. For example, an assessment published by the Cleveland Fed concluded:

“After staying relatively stable for several decades, intergenerational mobility appears to have declined sharply at some point between 1980 and 1990, a period in which both income inequality and the economic returns to education rose sharply. This finding is also consistent with theoretical models of intergenerational mobility that emphasize the role of human capital formation. There is fairly consistent evidence that intergenerational mobility has stayed roughly constant since 1990 but remains below the rates of mobility experienced from 1950 to 1980.”

While it would be wrong to take this statement as conclusive, it is also wrong to take the assessment of the study cited by Samuelson as conclusive and it is a gross misrepresentation to imply that this study examined patterns in mobility over the whole post-war period. It did not even try to examine changes in mobility over the 1980s, the period when patterns in inequality would have most likely led to a decline in mobility.

Note: Link fixed, thanks Dennis.

Robert Samuelson is happy to tell us that contrary to what he hoped some of us believed, there was not much change in mobility for children entering the labor force between the first President Bush and second President Bush’s administrations. Samuelson misrepresents the study to imply that it finds that there has been no change in mobility over the post-war period.

“By the conventional wisdom, American society is becoming more rigid. People’s place on the economic ladder (“relative mobility”) is increasingly fixed.

“Untrue, concludes the NBER study.”

Samuelson then notes the study’s finding that there has been little change in mobility for workers entering the labor market in 2007 compared to 1990. The study then refers to earlier work finding no change in mobility prior to 1990. This study did not itself examine the period prior to 1990.

This is important since that is the period in which we might have expected growing inequality to have a notable impact on mobility. There was some divergence between quintiles of income distribution in the 1980s. In the years since 1980, there has not been much divergence between the bottom half of the top quintile and the rest of the income distribution. Most of the inequality was associated with the pulling away of the one percent from everyone else. This study made no effort to examine mobility into the one percent.

As far as mobility in the years prior to the 1990, contrary to the claim of this study, the research is far from conclusive. For example, an assessment published by the Cleveland Fed concluded:

“After staying relatively stable for several decades, intergenerational mobility appears to have declined sharply at some point between 1980 and 1990, a period in which both income inequality and the economic returns to education rose sharply. This finding is also consistent with theoretical models of intergenerational mobility that emphasize the role of human capital formation. There is fairly consistent evidence that intergenerational mobility has stayed roughly constant since 1990 but remains below the rates of mobility experienced from 1950 to 1980.”

While it would be wrong to take this statement as conclusive, it is also wrong to take the assessment of the study cited by Samuelson as conclusive and it is a gross misrepresentation to imply that this study examined patterns in mobility over the whole post-war period. It did not even try to examine changes in mobility over the 1980s, the period when patterns in inequality would have most likely led to a decline in mobility.

Note: Link fixed, thanks Dennis.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I see they are playing the really big number game in my home town. The Chicago Tribune headlined a news story: “Chicago pension tab: $18,596 for every man, woman, child.” That’s pretty scary. Fortunately my Chicago public school teachers taught me about fractions and denominators. That is what is missing here.

The key point is that Chicago does not have to pay this money tomorrow or even over the next year. This is a liability over the next 30 years. The relevant denominator then is Chicago’s income over the next 30 years. I don’t have the time to check the city’s income data just now, but if we assume that disposable (after-tax) per capita income is the same as for the country as a whole ($40,000 a year), we get that the discounted value over the next 30 years will be roughly $1.1 million. (This assumes 2.4 percent average annual growth and a 3.0 percent real discount rate.)

I also don’t have time to review the basis for the $18,596 pension tab, which puts the unfunded liability at around $50 billion, almost twice the official figure. But taking the number at face value, we get a liability that is equal to 1.7 percent of the city’s projected income. That amount is hardly trivial, but also not obviously a path to poverty.

By comparison, the slowdown in health care cost growth over the last five years has probably saved Chicagoans at least this much money, with costs close to 10 percent less than what had been projected back in 2008. You didn’t see the big news articles touting the big dividends from lower costs? Oh well.

Anyhow, the unfunded pension liabilities are a big issue with some big villains. At the top of the list is Mayor Richard M. Daley who thought it was cool not to meet the city’s pension obligations for his last decade in office. Surprise, that leaves a shortfall. The bond rating agencies also should be strung up from the bridges over the Chicago river. They signed off on accounting back in the 1990s that assumed the stock bubble would continue growing ever larger. This meant that the city didn’t have to contribute anything to the pensions.

When the city got in the habit of not contributing in the boom, it became much more difficult to suddenly find the money in the bust. Hence we get Mayor Daley’s decision not to cough up the money the city owed. (Yes, this was predictable, as some of us said at the time.) These are the villains in this story, not the school teachers, the firefighters, and the garbage collectors who worked for these pensions in good faith. Not paying them the pensions they are owed is effectively theft and if Chicago is going to get into the game of stealing, it makes more sense to steal from the people who have the money than retired workers who will be living on a bit over $30,000 a year.

Full disclosure: My mother is a retired employee of the state of Illinois, so she may be among the pensioners who are on the chopping block in this story.

I see they are playing the really big number game in my home town. The Chicago Tribune headlined a news story: “Chicago pension tab: $18,596 for every man, woman, child.” That’s pretty scary. Fortunately my Chicago public school teachers taught me about fractions and denominators. That is what is missing here.

The key point is that Chicago does not have to pay this money tomorrow or even over the next year. This is a liability over the next 30 years. The relevant denominator then is Chicago’s income over the next 30 years. I don’t have the time to check the city’s income data just now, but if we assume that disposable (after-tax) per capita income is the same as for the country as a whole ($40,000 a year), we get that the discounted value over the next 30 years will be roughly $1.1 million. (This assumes 2.4 percent average annual growth and a 3.0 percent real discount rate.)

I also don’t have time to review the basis for the $18,596 pension tab, which puts the unfunded liability at around $50 billion, almost twice the official figure. But taking the number at face value, we get a liability that is equal to 1.7 percent of the city’s projected income. That amount is hardly trivial, but also not obviously a path to poverty.

By comparison, the slowdown in health care cost growth over the last five years has probably saved Chicagoans at least this much money, with costs close to 10 percent less than what had been projected back in 2008. You didn’t see the big news articles touting the big dividends from lower costs? Oh well.

Anyhow, the unfunded pension liabilities are a big issue with some big villains. At the top of the list is Mayor Richard M. Daley who thought it was cool not to meet the city’s pension obligations for his last decade in office. Surprise, that leaves a shortfall. The bond rating agencies also should be strung up from the bridges over the Chicago river. They signed off on accounting back in the 1990s that assumed the stock bubble would continue growing ever larger. This meant that the city didn’t have to contribute anything to the pensions.

When the city got in the habit of not contributing in the boom, it became much more difficult to suddenly find the money in the bust. Hence we get Mayor Daley’s decision not to cough up the money the city owed. (Yes, this was predictable, as some of us said at the time.) These are the villains in this story, not the school teachers, the firefighters, and the garbage collectors who worked for these pensions in good faith. Not paying them the pensions they are owed is effectively theft and if Chicago is going to get into the game of stealing, it makes more sense to steal from the people who have the money than retired workers who will be living on a bit over $30,000 a year.

Full disclosure: My mother is a retired employee of the state of Illinois, so she may be among the pensioners who are on the chopping block in this story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

And here at Beat the Press we are happy to oblige, at no charge to Mr. Lawrence. Brad Plumer caught Robert Lawrence claiming that increased oil production in the United States will not reduce the size of the trade deficit.

According to Brad, Lawrence said that the trade deficit is determined by the balance of domestic savings and investment. He then quotes Lawrence:

“Unless you can tell me how the oil boom will change that pattern of savings and investment … then it’s not going to change the trade balance.”

Of course we can tell him how the oil boom could change the balance of savings and investment. Let’s say that we had $100 billion going out of the country each year to buy oil from Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, and other foreign countries. This is $100 billion out of the pockets of U.S. consumers. It can be thought as equivalent to $100 billion tax. Consumers will reduce their spending by somewhere in the neighborhood of $90 billion (assume $10 billion of this money would have otherwise been saved) because of this drain from their pocketbooks.

Now suppose that we find some infinite pile of oil underneath Pennsylvania. Instead of sending the $100 billion to foreign countries we send it to oil companies and oil workers in Pennsylvania. While the situation of oil consumers has not changed (we’re all still out $100 billion), the money is now in the hands of people who will spend a large portion of it domestically. When they spend this money it will lead to more demand, employment, and output in the United States. (Some of the spending will of course go to imports.)

With higher output, we will also see more savings. If output increases by $100 billion, then savings may increase by around $10 billion. Tax collections will also increase while government spending on programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps will decrease. This will lead to a reduction in the government deficit (i.e. an increase in public savings, on the order of $25-$30 billion). On net, we can expect to see national savings increase in this story by around $35-$40 billion. This would imply a reduction in the trade deficit of roughly this amount.

Since our assignment from Professor Lawrence was simply to show him how increased domestic oil production can increase domestic savings, we have already finished the task. But, it might be helpful to provide him some further education on this topic.

Brad describes Lawrence as saying:

“If we’re buying more domestic oil instead of foreign oil, then the dollar will rise and we’ll switch to spending on other imported goods.”

This is not necessarily true. Many foreign countries, most notably China, have been buying up huge amounts of dollars to hold as reserves. One of their main motivations was to keep the dollar high against their currencies so as to protect their export markets in the United States. If the U.S. is sending fewer dollars abroad to buy oil, then they have to buy fewer dollars to keep a targeted value of their currency against the dollar. This means that other countries may respond to the reduced U.S. purchases of oil by buying up fewer dollars. If this proves to be the case, then there is no reason that the dollar must rise against other currencies.

So there you have it. The United States can reduce its trade deficit through more domestic oil production, as it has to some extent in the last five years. This can be associated with an increase in domestic savings and need not cause a rise in the value of the dollar. One day you may be able to learn these facts at Harvard, but in the meantime, you can get the scoop here at Beat the Press.

And here at Beat the Press we are happy to oblige, at no charge to Mr. Lawrence. Brad Plumer caught Robert Lawrence claiming that increased oil production in the United States will not reduce the size of the trade deficit.

According to Brad, Lawrence said that the trade deficit is determined by the balance of domestic savings and investment. He then quotes Lawrence:

“Unless you can tell me how the oil boom will change that pattern of savings and investment … then it’s not going to change the trade balance.”

Of course we can tell him how the oil boom could change the balance of savings and investment. Let’s say that we had $100 billion going out of the country each year to buy oil from Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, and other foreign countries. This is $100 billion out of the pockets of U.S. consumers. It can be thought as equivalent to $100 billion tax. Consumers will reduce their spending by somewhere in the neighborhood of $90 billion (assume $10 billion of this money would have otherwise been saved) because of this drain from their pocketbooks.

Now suppose that we find some infinite pile of oil underneath Pennsylvania. Instead of sending the $100 billion to foreign countries we send it to oil companies and oil workers in Pennsylvania. While the situation of oil consumers has not changed (we’re all still out $100 billion), the money is now in the hands of people who will spend a large portion of it domestically. When they spend this money it will lead to more demand, employment, and output in the United States. (Some of the spending will of course go to imports.)

With higher output, we will also see more savings. If output increases by $100 billion, then savings may increase by around $10 billion. Tax collections will also increase while government spending on programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps will decrease. This will lead to a reduction in the government deficit (i.e. an increase in public savings, on the order of $25-$30 billion). On net, we can expect to see national savings increase in this story by around $35-$40 billion. This would imply a reduction in the trade deficit of roughly this amount.

Since our assignment from Professor Lawrence was simply to show him how increased domestic oil production can increase domestic savings, we have already finished the task. But, it might be helpful to provide him some further education on this topic.

Brad describes Lawrence as saying:

“If we’re buying more domestic oil instead of foreign oil, then the dollar will rise and we’ll switch to spending on other imported goods.”

This is not necessarily true. Many foreign countries, most notably China, have been buying up huge amounts of dollars to hold as reserves. One of their main motivations was to keep the dollar high against their currencies so as to protect their export markets in the United States. If the U.S. is sending fewer dollars abroad to buy oil, then they have to buy fewer dollars to keep a targeted value of their currency against the dollar. This means that other countries may respond to the reduced U.S. purchases of oil by buying up fewer dollars. If this proves to be the case, then there is no reason that the dollar must rise against other currencies.

So there you have it. The United States can reduce its trade deficit through more domestic oil production, as it has to some extent in the last five years. This can be associated with an increase in domestic savings and need not cause a rise in the value of the dollar. One day you may be able to learn these facts at Harvard, but in the meantime, you can get the scoop here at Beat the Press.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión