The NYT had a peculiar account of the state of the economy in its lead up to the state of the union address. At one point it told readers that:

“several indicators show that the economy is in its best shape since he took office in 2009.”

This is peculiar since it would have been true in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 also. In effect, the recession could be seen as throwing the economy into a big hole. We have been climbing out of the hole ever since. It would take an extraordinary turn of events to throw us back down to the bottom of the hole so the real question is the rate at which we get out of the hole. Thus far the rate has been quite slow. Even if we sustain the somewhat faster growth rate projected for 2014 we would not be getting out of the hole (measured as returning to full employment) until the end of the decade.

The NYT had a peculiar account of the state of the economy in its lead up to the state of the union address. At one point it told readers that:

“several indicators show that the economy is in its best shape since he took office in 2009.”

This is peculiar since it would have been true in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 also. In effect, the recession could be seen as throwing the economy into a big hole. We have been climbing out of the hole ever since. It would take an extraordinary turn of events to throw us back down to the bottom of the hole so the real question is the rate at which we get out of the hole. Thus far the rate has been quite slow. Even if we sustain the somewhat faster growth rate projected for 2014 we would not be getting out of the hole (measured as returning to full employment) until the end of the decade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Budget reporters are apparently all in some secret fraternity in which they practice bizarre rituals like using numbers that will be meaningless to almost of their readers. Hence we get the Washington Post telling us:

“Negotiators agreed Monday evening on a new five-year Farm Bill that slashes about $23 billion in federal spending by ending direct payments to farmers, consolidating dozens of Agriculture Department programs and by cutting about $8 billion in food stamp assistance.”

Okay, how big a deal is savings $8 billion on food stamps over the next five years or $23 billion on the whole bill? Sure, everyone knows the significance of these numbers because they’ve been reading through the Office of Management and Budget’s projection for the next decade.

This is just asinine. The Post’s reporters and editors know that almost none of their readers have any sense of what these numbers mean in terms of the total budget or their own pocket book. They are just really big numbers, as David Leonhardt the former Washington editor of the NYT said. Since almost no one reading these numbers can attach any meaning to them, the purpose of putting them in the paper cannot be to inform readers. Obviously the motive here is to comply with the bizarre fraternity ritual of budget reporters.

It is not hard to express these numbers in ways that would convey information to the vast majority of readers. A quick trip to CEPR’s Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator would tell readers that the $23 billion cut amounts to 0.11 percent of projected federal spending while the $8 billion cut in food stamps would reduce federal spending by 0.04 percent. Now you know how much consequence these items have for the budget and your tax bill. Maybe one day we will have reporters and news outlets that put informing their audience above fraternity rituals, but not this day.

Budget reporters are apparently all in some secret fraternity in which they practice bizarre rituals like using numbers that will be meaningless to almost of their readers. Hence we get the Washington Post telling us:

“Negotiators agreed Monday evening on a new five-year Farm Bill that slashes about $23 billion in federal spending by ending direct payments to farmers, consolidating dozens of Agriculture Department programs and by cutting about $8 billion in food stamp assistance.”

Okay, how big a deal is savings $8 billion on food stamps over the next five years or $23 billion on the whole bill? Sure, everyone knows the significance of these numbers because they’ve been reading through the Office of Management and Budget’s projection for the next decade.

This is just asinine. The Post’s reporters and editors know that almost none of their readers have any sense of what these numbers mean in terms of the total budget or their own pocket book. They are just really big numbers, as David Leonhardt the former Washington editor of the NYT said. Since almost no one reading these numbers can attach any meaning to them, the purpose of putting them in the paper cannot be to inform readers. Obviously the motive here is to comply with the bizarre fraternity ritual of budget reporters.

It is not hard to express these numbers in ways that would convey information to the vast majority of readers. A quick trip to CEPR’s Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator would tell readers that the $23 billion cut amounts to 0.11 percent of projected federal spending while the $8 billion cut in food stamps would reduce federal spending by 0.04 percent. Now you know how much consequence these items have for the budget and your tax bill. Maybe one day we will have reporters and news outlets that put informing their audience above fraternity rituals, but not this day.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The story of the housing bubble and the impact of its bursting is pretty damn simple. If we go back to the bubble years, 2002-2007, the housing market was driving the economy. It was doing this both directly as construction spending peaked at close to 6.5 percent of GDP, two percentage points above its average over the prior two decades. It also drove consumption as people spent based on the equity in their home created by the bubble. The savings rate fell to almost zero based on this housing wealth effect.

When the bubble burst, we had nothing to replace the lost demand. Housing construction fell to well below normal levels in response to the huge overbuilding of the bubble years. At the trough construction was down by more than 4.0 percentage points of GDP or $660 billion a year in today’s economy. Consumption also fell as the home equity that was driving it disappeared. If we assume a housing wealth effect of 5-7 percent (i.e. a dollar of housing wealth increases annual consumption by 5-7 cents) then the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth would correspond to a reduction in annual consumption of between $400 billion and $560 billion. Taken together, the loss of construction and consumption spending imply a loss in annual demand of more than $1 trillion.

That’s the basic story, unfortunately it is far too simple for most analysts to understand. Hence we have Robert Samuelson bemoaning the fact that the Fed wasn’t able to instill the confidence to get businesses to invest and consumers to spend. The problem with the Samuelson story is that its basic facts are wrong.

Non-residential investment is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. Given the weak demand in the economy, this is very impressive. It certainly doesn’t give any evidence of a lack of confidence. And consumers are spending. The savings rate is now below 5.0 percent of GDP. This compares to a pre-stock and housing bubble average of more than 10.0 percent of GDP. The only time that the saving rate has been lower has been at the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles. In short, Samuelson is looking for an explanation for weaknesses in spending that do not exist.

The need for additional demand stems primarily from the trade deficit. This creates a gap in demand of roughly 3.0 percent of GDP, which would be closer to 4.0 percent of GDP if we were at full employment. For some reason, Samuelson doesn’t discuss this issue, perhaps because he doesn’t have access to the data.

(Reports are that Ezra Klein left the Post because it’s so hard to get government data there.)

The story of the housing bubble and the impact of its bursting is pretty damn simple. If we go back to the bubble years, 2002-2007, the housing market was driving the economy. It was doing this both directly as construction spending peaked at close to 6.5 percent of GDP, two percentage points above its average over the prior two decades. It also drove consumption as people spent based on the equity in their home created by the bubble. The savings rate fell to almost zero based on this housing wealth effect.

When the bubble burst, we had nothing to replace the lost demand. Housing construction fell to well below normal levels in response to the huge overbuilding of the bubble years. At the trough construction was down by more than 4.0 percentage points of GDP or $660 billion a year in today’s economy. Consumption also fell as the home equity that was driving it disappeared. If we assume a housing wealth effect of 5-7 percent (i.e. a dollar of housing wealth increases annual consumption by 5-7 cents) then the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth would correspond to a reduction in annual consumption of between $400 billion and $560 billion. Taken together, the loss of construction and consumption spending imply a loss in annual demand of more than $1 trillion.

That’s the basic story, unfortunately it is far too simple for most analysts to understand. Hence we have Robert Samuelson bemoaning the fact that the Fed wasn’t able to instill the confidence to get businesses to invest and consumers to spend. The problem with the Samuelson story is that its basic facts are wrong.

Non-residential investment is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. Given the weak demand in the economy, this is very impressive. It certainly doesn’t give any evidence of a lack of confidence. And consumers are spending. The savings rate is now below 5.0 percent of GDP. This compares to a pre-stock and housing bubble average of more than 10.0 percent of GDP. The only time that the saving rate has been lower has been at the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles. In short, Samuelson is looking for an explanation for weaknesses in spending that do not exist.

The need for additional demand stems primarily from the trade deficit. This creates a gap in demand of roughly 3.0 percent of GDP, which would be closer to 4.0 percent of GDP if we were at full employment. For some reason, Samuelson doesn’t discuss this issue, perhaps because he doesn’t have access to the data.

(Reports are that Ezra Klein left the Post because it’s so hard to get government data there.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steven Rattner took up large chunks of the NYT opinion section to express confused thoughts on manufacturing. Rattner sorts of meanders everywhere and back. The government should help manufacturing, but not like Solyndra and Fisker. Right, we don’t want help the losers, we just want to help all the companies that got loans and were successful. Does Rattner want to tell us how we would determine in advance which ones those will be?

We want better education. Sure, that’s great, any ideas on how we should do that?

It’s hardly worth going through all the silliness in Rattner’s piece, rather I will just mention the incredible bottom line. Rattner never once mentions the value of the dollar. This happens to be huge. If Rattner has access to government data he would know that manufacturing employment first began to fall in the late 1990s, even as the economy was booming, after the dollar soared due to the botched bailout from the East Asian financial crisis. The run-up in the dollar had the equivalent effect of placing a 30 percent tariff on our exports and giving a 30 percent subsidy for imports. Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that manufacturing employment fell and the trade deficit soared.

Rattner’s confusion about trade and the value of the dollar extends to his endorsement of new “trade” deals. Of course agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade barriers, they are about imposing corporate friendly regulations on the U.S. and our trading partners.

Among the top priority for U.S. negotiators is increasing the strength of patent protection for prescription drugs. Insofar as they succeed it will mean that foreigners will have to pay more money to Pfizer and Merck, which means that they will have less money to buy U.S. manufactured goods. That is hurting, not helping U.S. manufacturing . That one should be simple enough even for Steven Rattner to understand.

Steven Rattner took up large chunks of the NYT opinion section to express confused thoughts on manufacturing. Rattner sorts of meanders everywhere and back. The government should help manufacturing, but not like Solyndra and Fisker. Right, we don’t want help the losers, we just want to help all the companies that got loans and were successful. Does Rattner want to tell us how we would determine in advance which ones those will be?

We want better education. Sure, that’s great, any ideas on how we should do that?

It’s hardly worth going through all the silliness in Rattner’s piece, rather I will just mention the incredible bottom line. Rattner never once mentions the value of the dollar. This happens to be huge. If Rattner has access to government data he would know that manufacturing employment first began to fall in the late 1990s, even as the economy was booming, after the dollar soared due to the botched bailout from the East Asian financial crisis. The run-up in the dollar had the equivalent effect of placing a 30 percent tariff on our exports and giving a 30 percent subsidy for imports. Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that manufacturing employment fell and the trade deficit soared.

Rattner’s confusion about trade and the value of the dollar extends to his endorsement of new “trade” deals. Of course agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade barriers, they are about imposing corporate friendly regulations on the U.S. and our trading partners.

Among the top priority for U.S. negotiators is increasing the strength of patent protection for prescription drugs. Insofar as they succeed it will mean that foreigners will have to pay more money to Pfizer and Merck, which means that they will have less money to buy U.S. manufactured goods. That is hurting, not helping U.S. manufacturing . That one should be simple enough even for Steven Rattner to understand.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

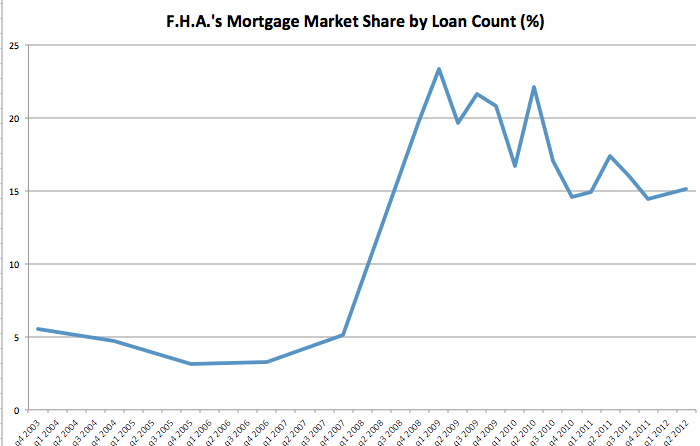

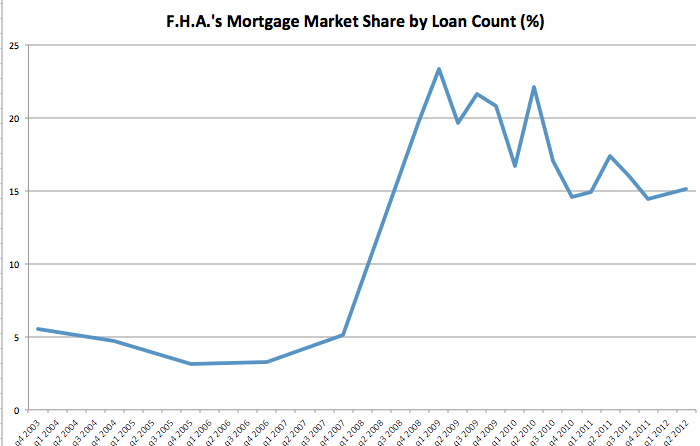

One of the reasons that the housing bubble caught so many people by surprise was that the media relied largely on people who had an interest in pushing housing as their sources in reporting. This still seems to be the case today as indicated by a NYT piece on the housing market.

At one point the piece cites economist Mark Zandi, telling readers:

“Tighter lending standards are shutting out close to 12.5 million consumers who would qualify in normal times.”

It’s difficult to attach any meaning to this statement. We currently have 75 million home owning households and 40 million renting households. Is Zandi saying that among the 40 million renting households we have 12.5 million people who would in other times qualify for mortgages but do not today? Many renters do now qualify for a mortgage. If we say that a quarter of renters could now buy a home if they wanted, then Zandi’s claim would be that 12.5 million of the 30 million remaining renters (42 percent) would in normal times be able to get mortgages but are unable to do so because of tight credit conditions today. That one is a bit hard to believe. (It’s possible that the number includes people who can’t refinance because they have little or no equity in their home, but that is a very different issue.)

In the same vein, the piece tells readers:

“Mortgages are roughly seven times harder to get than they were five years ago, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s credit availability index, and they show few signs of getting easier.”

The seven times harder refers to an index that the Mortgage Bankers Association constructed that is at one seventh of its value five years ago. It doesn’t mean that a person has one seventh the chance of getting a mortgage.

Incredibly this piece never mentions the role of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). While the FHA virtually disappeared as a factor in the housing market at the peak of the housing boom, because it did not relax its standards, its role hugely expanded after the crash. When the housing market was bottoming out in 2009 and 2010 it guaranteed more than 20 percent of new mortgages. It still insures close to 15 percent. Many people who would not meet the standards for a Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac mortgages can get one insured by the FHA.

Source: Business Insider/HUD.

One of the reasons that the housing bubble caught so many people by surprise was that the media relied largely on people who had an interest in pushing housing as their sources in reporting. This still seems to be the case today as indicated by a NYT piece on the housing market.

At one point the piece cites economist Mark Zandi, telling readers:

“Tighter lending standards are shutting out close to 12.5 million consumers who would qualify in normal times.”

It’s difficult to attach any meaning to this statement. We currently have 75 million home owning households and 40 million renting households. Is Zandi saying that among the 40 million renting households we have 12.5 million people who would in other times qualify for mortgages but do not today? Many renters do now qualify for a mortgage. If we say that a quarter of renters could now buy a home if they wanted, then Zandi’s claim would be that 12.5 million of the 30 million remaining renters (42 percent) would in normal times be able to get mortgages but are unable to do so because of tight credit conditions today. That one is a bit hard to believe. (It’s possible that the number includes people who can’t refinance because they have little or no equity in their home, but that is a very different issue.)

In the same vein, the piece tells readers:

“Mortgages are roughly seven times harder to get than they were five years ago, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s credit availability index, and they show few signs of getting easier.”

The seven times harder refers to an index that the Mortgage Bankers Association constructed that is at one seventh of its value five years ago. It doesn’t mean that a person has one seventh the chance of getting a mortgage.

Incredibly this piece never mentions the role of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). While the FHA virtually disappeared as a factor in the housing market at the peak of the housing boom, because it did not relax its standards, its role hugely expanded after the crash. When the housing market was bottoming out in 2009 and 2010 it guaranteed more than 20 percent of new mortgages. It still insures close to 15 percent. Many people who would not meet the standards for a Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac mortgages can get one insured by the FHA.

Source: Business Insider/HUD.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

All Things Considered ran a piece making the obvious point, it doesn’t matter for the finances of the health insurance exchanges whether or not young people sign up. What matters is that healthy people sign up. Some of us have been making this point for a while, but it’s great to see that major national news outlets are capable of learning.

All Things Considered ran a piece making the obvious point, it doesn’t matter for the finances of the health insurance exchanges whether or not young people sign up. What matters is that healthy people sign up. Some of us have been making this point for a while, but it’s great to see that major national news outlets are capable of learning.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

For all its many flaws Obamacare will prove to be a great thing for the simple reason that it will guarantee most of the population affordable health care insurance. The key group here is not the uninsured, many of whom will be able to get insurance as a result of the law, but rather the bulk of the under age 65 population whose insurance depends on their job. For the first time, these people will be in a situation where if they lose their job, they will still be able to get insurance they can afford. (Yes, I know that not everyone will find the insurance available through the exchanges affordable, hence the use of the word “most.”)

Anyhow, it is fascinating to see the continuing vitriole of the right against Obamacare, which is bearing ever less relationship to reality. We have heard endless talk about how Obamacare was creating a “part-time nation” as employers reduced work hours to get under the 30-hour cutoff for employer sanctions under the ACA. This one suffers from the problem that there were fewer people reported as working part-time at the end of 2013 than at the end of 2012. (Some of us are fans of voluntary part-time employment.)

Ed Rogers, writing in the Washington Post, told readers that the number of uninsured was rising because Target had stopped offering insurance to part-time workers. (Apart from the limited impact of the insurance status of Target’s part-time employees on national insurance rates, it is possible that Target stopped offering part-timers the option to buy into their insurance because few were taking it, given the expansion of Medicaid and the subsidies in the exchanges under the ACA.)

Wilson then linked to a “smart piece” by Megan McArdle which touted the imminent demise of Obamacare. Among the troubles of Obamacare cited by McArdle is that many of the people now signing up for Medicaid were already eligible before the ACA. This is an interesting claim, but so what if it is true? They previously had not been covered, now they are. And the problem is?

Another of the highlights is that the $2,500 in savings for a typical family has not materialized. Actually slower growth in health care costs have reduced spending by more than 10 percent compared to what was projected in 2008. That would translate into savings in the ballpark of $2,500 for a family of four. Clearly much of the slower cost growth was not due to the ACA, but does anyone doubt that if cost growth had accelerated it would be blamed on the ACA?

Anyhow, as the exchanges and Medicaid expansion become more a part of the health care framework, the ACA is going to gain increased acceptance even by Republicans, just as Medicare did. At some point, clever Republican politicians will recognize this fact and adjust their message to stay in line with their base. Meanwhile, the dead enders will get ever further removed from reality as they continue to push for the repeal of Obamacare.

For all its many flaws Obamacare will prove to be a great thing for the simple reason that it will guarantee most of the population affordable health care insurance. The key group here is not the uninsured, many of whom will be able to get insurance as a result of the law, but rather the bulk of the under age 65 population whose insurance depends on their job. For the first time, these people will be in a situation where if they lose their job, they will still be able to get insurance they can afford. (Yes, I know that not everyone will find the insurance available through the exchanges affordable, hence the use of the word “most.”)

Anyhow, it is fascinating to see the continuing vitriole of the right against Obamacare, which is bearing ever less relationship to reality. We have heard endless talk about how Obamacare was creating a “part-time nation” as employers reduced work hours to get under the 30-hour cutoff for employer sanctions under the ACA. This one suffers from the problem that there were fewer people reported as working part-time at the end of 2013 than at the end of 2012. (Some of us are fans of voluntary part-time employment.)

Ed Rogers, writing in the Washington Post, told readers that the number of uninsured was rising because Target had stopped offering insurance to part-time workers. (Apart from the limited impact of the insurance status of Target’s part-time employees on national insurance rates, it is possible that Target stopped offering part-timers the option to buy into their insurance because few were taking it, given the expansion of Medicaid and the subsidies in the exchanges under the ACA.)

Wilson then linked to a “smart piece” by Megan McArdle which touted the imminent demise of Obamacare. Among the troubles of Obamacare cited by McArdle is that many of the people now signing up for Medicaid were already eligible before the ACA. This is an interesting claim, but so what if it is true? They previously had not been covered, now they are. And the problem is?

Another of the highlights is that the $2,500 in savings for a typical family has not materialized. Actually slower growth in health care costs have reduced spending by more than 10 percent compared to what was projected in 2008. That would translate into savings in the ballpark of $2,500 for a family of four. Clearly much of the slower cost growth was not due to the ACA, but does anyone doubt that if cost growth had accelerated it would be blamed on the ACA?

Anyhow, as the exchanges and Medicaid expansion become more a part of the health care framework, the ACA is going to gain increased acceptance even by Republicans, just as Medicare did. At some point, clever Republican politicians will recognize this fact and adjust their message to stay in line with their base. Meanwhile, the dead enders will get ever further removed from reality as they continue to push for the repeal of Obamacare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

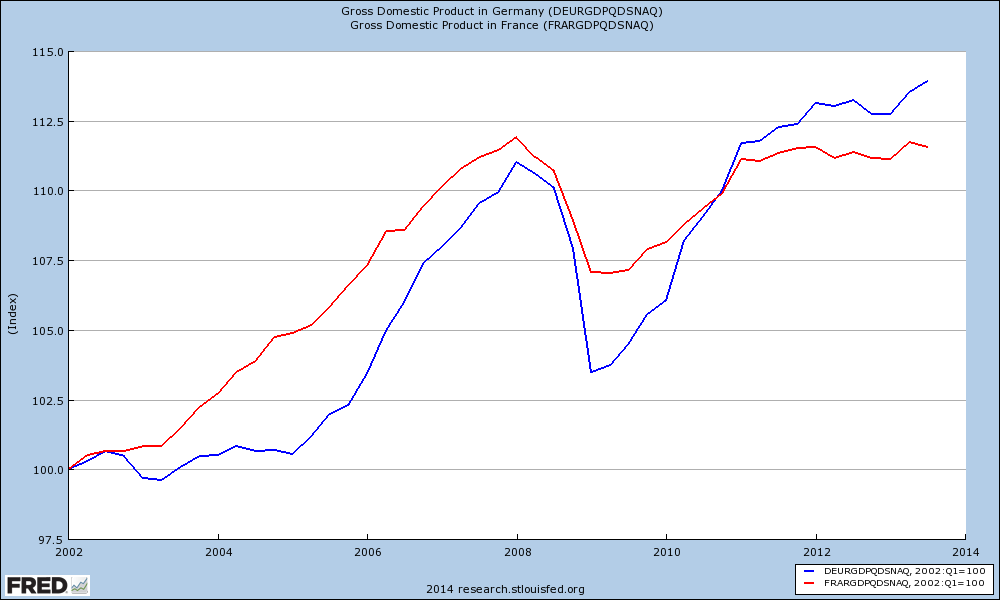

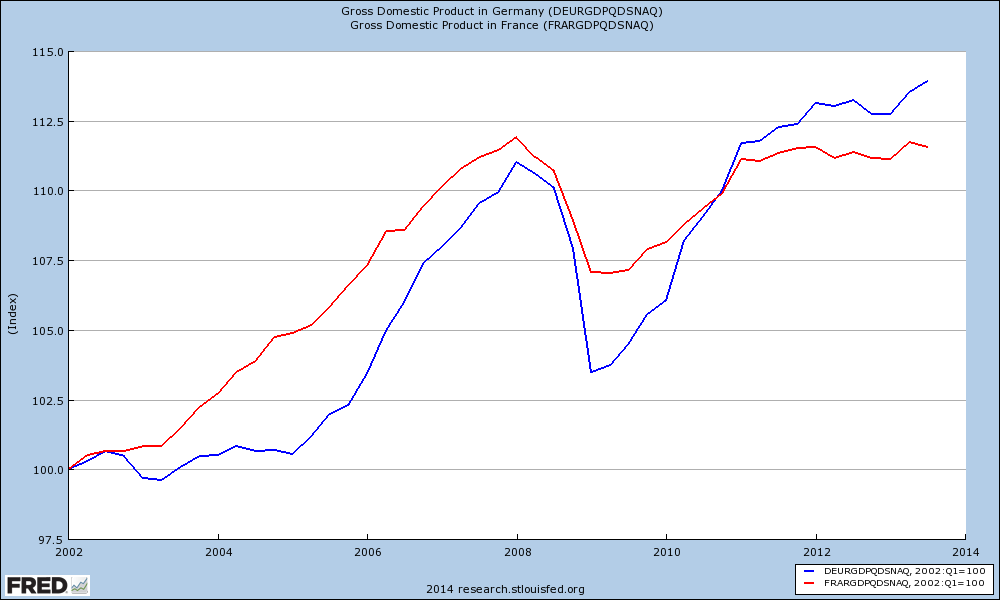

The mythical German economic boom, along with Santa Claus and the Loch Ness Monster, made an appearance in Roger Cohen’s NYT column this morning. (Actually, Santa is still recovering from his busy Christmas and Nessie is hiding, but the German boom is there, really.) Cohen tells readers that Germany did the right thing when its Social Democratic government weakened its welfare state. He now is pleased that France’s Socialist President Francois Hollande is about to follow suit.

“The German left partially dismantled the welfare state built by the German left. Unemployment fell, the economy boomed. Germany today is Germany and France is France.”

Let’s see, Germany boomed and France is France. Let’s check the score on that one. Here’s growth from 2002 to 2013 in the two countries. [I have corrected this to show more recent data, thanks Mark.]

Germany shows a hair more growth through the summer of 2013, but is a cumulative difference of 2.4 percentage points of growth over 11 years (0.2 percentage points a year) the difference between a booming economy and France? This is not trivial, but I’m not sure it is exactly the difference between a booming economy and a stagnant one. (The difference is somewhat larger in per capita terms. Germany’s population is shrinking slowly while France’s is growing. Some folks consider the latter a big positive, although I’m not in that camp. I have nothing against French people, but I don’t see how they are doing the world a service by producing more of them.)

While the difference in growth rates since Germany’s weakening of its welfare state may not justify Cohen’s celebration of a booming German economy, there is a notable difference in labor market outcomes. In the most recent data Germany has an unemployment rate of 5.2 percent while France has an unemployment rate of 10.8 percent.

This gap cannot be explained by the differences in growth rates in the two countries. Rather it stems from Germany’s aggressive use of work sharing and other policies designed to keep workers on the payroll even if it means a reduction in work hours. If Hollande wanted to copy a policy from Germany he might have looked to its success with work sharing. That policy has been far more successful in lowering unemployment than cuts in the welfare state have been in promoting growth.

Note: In response to comments, France is red, Germany is blue.

The mythical German economic boom, along with Santa Claus and the Loch Ness Monster, made an appearance in Roger Cohen’s NYT column this morning. (Actually, Santa is still recovering from his busy Christmas and Nessie is hiding, but the German boom is there, really.) Cohen tells readers that Germany did the right thing when its Social Democratic government weakened its welfare state. He now is pleased that France’s Socialist President Francois Hollande is about to follow suit.

“The German left partially dismantled the welfare state built by the German left. Unemployment fell, the economy boomed. Germany today is Germany and France is France.”

Let’s see, Germany boomed and France is France. Let’s check the score on that one. Here’s growth from 2002 to 2013 in the two countries. [I have corrected this to show more recent data, thanks Mark.]

Germany shows a hair more growth through the summer of 2013, but is a cumulative difference of 2.4 percentage points of growth over 11 years (0.2 percentage points a year) the difference between a booming economy and France? This is not trivial, but I’m not sure it is exactly the difference between a booming economy and a stagnant one. (The difference is somewhat larger in per capita terms. Germany’s population is shrinking slowly while France’s is growing. Some folks consider the latter a big positive, although I’m not in that camp. I have nothing against French people, but I don’t see how they are doing the world a service by producing more of them.)

While the difference in growth rates since Germany’s weakening of its welfare state may not justify Cohen’s celebration of a booming German economy, there is a notable difference in labor market outcomes. In the most recent data Germany has an unemployment rate of 5.2 percent while France has an unemployment rate of 10.8 percent.

This gap cannot be explained by the differences in growth rates in the two countries. Rather it stems from Germany’s aggressive use of work sharing and other policies designed to keep workers on the payroll even if it means a reduction in work hours. If Hollande wanted to copy a policy from Germany he might have looked to its success with work sharing. That policy has been far more successful in lowering unemployment than cuts in the welfare state have been in promoting growth.

Note: In response to comments, France is red, Germany is blue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión