I see they are playing the really big number game in my home town. The Chicago Tribune headlined a news story: “Chicago pension tab: $18,596 for every man, woman, child.” That’s pretty scary. Fortunately my Chicago public school teachers taught me about fractions and denominators. That is what is missing here.

The key point is that Chicago does not have to pay this money tomorrow or even over the next year. This is a liability over the next 30 years. The relevant denominator then is Chicago’s income over the next 30 years. I don’t have the time to check the city’s income data just now, but if we assume that disposable (after-tax) per capita income is the same as for the country as a whole ($40,000 a year), we get that the discounted value over the next 30 years will be roughly $1.1 million. (This assumes 2.4 percent average annual growth and a 3.0 percent real discount rate.)

I also don’t have time to review the basis for the $18,596 pension tab, which puts the unfunded liability at around $50 billion, almost twice the official figure. But taking the number at face value, we get a liability that is equal to 1.7 percent of the city’s projected income. That amount is hardly trivial, but also not obviously a path to poverty.

By comparison, the slowdown in health care cost growth over the last five years has probably saved Chicagoans at least this much money, with costs close to 10 percent less than what had been projected back in 2008. You didn’t see the big news articles touting the big dividends from lower costs? Oh well.

Anyhow, the unfunded pension liabilities are a big issue with some big villains. At the top of the list is Mayor Richard M. Daley who thought it was cool not to meet the city’s pension obligations for his last decade in office. Surprise, that leaves a shortfall. The bond rating agencies also should be strung up from the bridges over the Chicago river. They signed off on accounting back in the 1990s that assumed the stock bubble would continue growing ever larger. This meant that the city didn’t have to contribute anything to the pensions.

When the city got in the habit of not contributing in the boom, it became much more difficult to suddenly find the money in the bust. Hence we get Mayor Daley’s decision not to cough up the money the city owed. (Yes, this was predictable, as some of us said at the time.) These are the villains in this story, not the school teachers, the firefighters, and the garbage collectors who worked for these pensions in good faith. Not paying them the pensions they are owed is effectively theft and if Chicago is going to get into the game of stealing, it makes more sense to steal from the people who have the money than retired workers who will be living on a bit over $30,000 a year.

Full disclosure: My mother is a retired employee of the state of Illinois, so she may be among the pensioners who are on the chopping block in this story.

I see they are playing the really big number game in my home town. The Chicago Tribune headlined a news story: “Chicago pension tab: $18,596 for every man, woman, child.” That’s pretty scary. Fortunately my Chicago public school teachers taught me about fractions and denominators. That is what is missing here.

The key point is that Chicago does not have to pay this money tomorrow or even over the next year. This is a liability over the next 30 years. The relevant denominator then is Chicago’s income over the next 30 years. I don’t have the time to check the city’s income data just now, but if we assume that disposable (after-tax) per capita income is the same as for the country as a whole ($40,000 a year), we get that the discounted value over the next 30 years will be roughly $1.1 million. (This assumes 2.4 percent average annual growth and a 3.0 percent real discount rate.)

I also don’t have time to review the basis for the $18,596 pension tab, which puts the unfunded liability at around $50 billion, almost twice the official figure. But taking the number at face value, we get a liability that is equal to 1.7 percent of the city’s projected income. That amount is hardly trivial, but also not obviously a path to poverty.

By comparison, the slowdown in health care cost growth over the last five years has probably saved Chicagoans at least this much money, with costs close to 10 percent less than what had been projected back in 2008. You didn’t see the big news articles touting the big dividends from lower costs? Oh well.

Anyhow, the unfunded pension liabilities are a big issue with some big villains. At the top of the list is Mayor Richard M. Daley who thought it was cool not to meet the city’s pension obligations for his last decade in office. Surprise, that leaves a shortfall. The bond rating agencies also should be strung up from the bridges over the Chicago river. They signed off on accounting back in the 1990s that assumed the stock bubble would continue growing ever larger. This meant that the city didn’t have to contribute anything to the pensions.

When the city got in the habit of not contributing in the boom, it became much more difficult to suddenly find the money in the bust. Hence we get Mayor Daley’s decision not to cough up the money the city owed. (Yes, this was predictable, as some of us said at the time.) These are the villains in this story, not the school teachers, the firefighters, and the garbage collectors who worked for these pensions in good faith. Not paying them the pensions they are owed is effectively theft and if Chicago is going to get into the game of stealing, it makes more sense to steal from the people who have the money than retired workers who will be living on a bit over $30,000 a year.

Full disclosure: My mother is a retired employee of the state of Illinois, so she may be among the pensioners who are on the chopping block in this story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

And here at Beat the Press we are happy to oblige, at no charge to Mr. Lawrence. Brad Plumer caught Robert Lawrence claiming that increased oil production in the United States will not reduce the size of the trade deficit.

According to Brad, Lawrence said that the trade deficit is determined by the balance of domestic savings and investment. He then quotes Lawrence:

“Unless you can tell me how the oil boom will change that pattern of savings and investment … then it’s not going to change the trade balance.”

Of course we can tell him how the oil boom could change the balance of savings and investment. Let’s say that we had $100 billion going out of the country each year to buy oil from Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, and other foreign countries. This is $100 billion out of the pockets of U.S. consumers. It can be thought as equivalent to $100 billion tax. Consumers will reduce their spending by somewhere in the neighborhood of $90 billion (assume $10 billion of this money would have otherwise been saved) because of this drain from their pocketbooks.

Now suppose that we find some infinite pile of oil underneath Pennsylvania. Instead of sending the $100 billion to foreign countries we send it to oil companies and oil workers in Pennsylvania. While the situation of oil consumers has not changed (we’re all still out $100 billion), the money is now in the hands of people who will spend a large portion of it domestically. When they spend this money it will lead to more demand, employment, and output in the United States. (Some of the spending will of course go to imports.)

With higher output, we will also see more savings. If output increases by $100 billion, then savings may increase by around $10 billion. Tax collections will also increase while government spending on programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps will decrease. This will lead to a reduction in the government deficit (i.e. an increase in public savings, on the order of $25-$30 billion). On net, we can expect to see national savings increase in this story by around $35-$40 billion. This would imply a reduction in the trade deficit of roughly this amount.

Since our assignment from Professor Lawrence was simply to show him how increased domestic oil production can increase domestic savings, we have already finished the task. But, it might be helpful to provide him some further education on this topic.

Brad describes Lawrence as saying:

“If we’re buying more domestic oil instead of foreign oil, then the dollar will rise and we’ll switch to spending on other imported goods.”

This is not necessarily true. Many foreign countries, most notably China, have been buying up huge amounts of dollars to hold as reserves. One of their main motivations was to keep the dollar high against their currencies so as to protect their export markets in the United States. If the U.S. is sending fewer dollars abroad to buy oil, then they have to buy fewer dollars to keep a targeted value of their currency against the dollar. This means that other countries may respond to the reduced U.S. purchases of oil by buying up fewer dollars. If this proves to be the case, then there is no reason that the dollar must rise against other currencies.

So there you have it. The United States can reduce its trade deficit through more domestic oil production, as it has to some extent in the last five years. This can be associated with an increase in domestic savings and need not cause a rise in the value of the dollar. One day you may be able to learn these facts at Harvard, but in the meantime, you can get the scoop here at Beat the Press.

And here at Beat the Press we are happy to oblige, at no charge to Mr. Lawrence. Brad Plumer caught Robert Lawrence claiming that increased oil production in the United States will not reduce the size of the trade deficit.

According to Brad, Lawrence said that the trade deficit is determined by the balance of domestic savings and investment. He then quotes Lawrence:

“Unless you can tell me how the oil boom will change that pattern of savings and investment … then it’s not going to change the trade balance.”

Of course we can tell him how the oil boom could change the balance of savings and investment. Let’s say that we had $100 billion going out of the country each year to buy oil from Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, and other foreign countries. This is $100 billion out of the pockets of U.S. consumers. It can be thought as equivalent to $100 billion tax. Consumers will reduce their spending by somewhere in the neighborhood of $90 billion (assume $10 billion of this money would have otherwise been saved) because of this drain from their pocketbooks.

Now suppose that we find some infinite pile of oil underneath Pennsylvania. Instead of sending the $100 billion to foreign countries we send it to oil companies and oil workers in Pennsylvania. While the situation of oil consumers has not changed (we’re all still out $100 billion), the money is now in the hands of people who will spend a large portion of it domestically. When they spend this money it will lead to more demand, employment, and output in the United States. (Some of the spending will of course go to imports.)

With higher output, we will also see more savings. If output increases by $100 billion, then savings may increase by around $10 billion. Tax collections will also increase while government spending on programs like unemployment insurance and food stamps will decrease. This will lead to a reduction in the government deficit (i.e. an increase in public savings, on the order of $25-$30 billion). On net, we can expect to see national savings increase in this story by around $35-$40 billion. This would imply a reduction in the trade deficit of roughly this amount.

Since our assignment from Professor Lawrence was simply to show him how increased domestic oil production can increase domestic savings, we have already finished the task. But, it might be helpful to provide him some further education on this topic.

Brad describes Lawrence as saying:

“If we’re buying more domestic oil instead of foreign oil, then the dollar will rise and we’ll switch to spending on other imported goods.”

This is not necessarily true. Many foreign countries, most notably China, have been buying up huge amounts of dollars to hold as reserves. One of their main motivations was to keep the dollar high against their currencies so as to protect their export markets in the United States. If the U.S. is sending fewer dollars abroad to buy oil, then they have to buy fewer dollars to keep a targeted value of their currency against the dollar. This means that other countries may respond to the reduced U.S. purchases of oil by buying up fewer dollars. If this proves to be the case, then there is no reason that the dollar must rise against other currencies.

So there you have it. The United States can reduce its trade deficit through more domestic oil production, as it has to some extent in the last five years. This can be associated with an increase in domestic savings and need not cause a rise in the value of the dollar. One day you may be able to learn these facts at Harvard, but in the meantime, you can get the scoop here at Beat the Press.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a peculiar account of the state of the economy in its lead up to the state of the union address. At one point it told readers that:

“several indicators show that the economy is in its best shape since he took office in 2009.”

This is peculiar since it would have been true in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 also. In effect, the recession could be seen as throwing the economy into a big hole. We have been climbing out of the hole ever since. It would take an extraordinary turn of events to throw us back down to the bottom of the hole so the real question is the rate at which we get out of the hole. Thus far the rate has been quite slow. Even if we sustain the somewhat faster growth rate projected for 2014 we would not be getting out of the hole (measured as returning to full employment) until the end of the decade.

The NYT had a peculiar account of the state of the economy in its lead up to the state of the union address. At one point it told readers that:

“several indicators show that the economy is in its best shape since he took office in 2009.”

This is peculiar since it would have been true in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 also. In effect, the recession could be seen as throwing the economy into a big hole. We have been climbing out of the hole ever since. It would take an extraordinary turn of events to throw us back down to the bottom of the hole so the real question is the rate at which we get out of the hole. Thus far the rate has been quite slow. Even if we sustain the somewhat faster growth rate projected for 2014 we would not be getting out of the hole (measured as returning to full employment) until the end of the decade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Budget reporters are apparently all in some secret fraternity in which they practice bizarre rituals like using numbers that will be meaningless to almost of their readers. Hence we get the Washington Post telling us:

“Negotiators agreed Monday evening on a new five-year Farm Bill that slashes about $23 billion in federal spending by ending direct payments to farmers, consolidating dozens of Agriculture Department programs and by cutting about $8 billion in food stamp assistance.”

Okay, how big a deal is savings $8 billion on food stamps over the next five years or $23 billion on the whole bill? Sure, everyone knows the significance of these numbers because they’ve been reading through the Office of Management and Budget’s projection for the next decade.

This is just asinine. The Post’s reporters and editors know that almost none of their readers have any sense of what these numbers mean in terms of the total budget or their own pocket book. They are just really big numbers, as David Leonhardt the former Washington editor of the NYT said. Since almost no one reading these numbers can attach any meaning to them, the purpose of putting them in the paper cannot be to inform readers. Obviously the motive here is to comply with the bizarre fraternity ritual of budget reporters.

It is not hard to express these numbers in ways that would convey information to the vast majority of readers. A quick trip to CEPR’s Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator would tell readers that the $23 billion cut amounts to 0.11 percent of projected federal spending while the $8 billion cut in food stamps would reduce federal spending by 0.04 percent. Now you know how much consequence these items have for the budget and your tax bill. Maybe one day we will have reporters and news outlets that put informing their audience above fraternity rituals, but not this day.

Budget reporters are apparently all in some secret fraternity in which they practice bizarre rituals like using numbers that will be meaningless to almost of their readers. Hence we get the Washington Post telling us:

“Negotiators agreed Monday evening on a new five-year Farm Bill that slashes about $23 billion in federal spending by ending direct payments to farmers, consolidating dozens of Agriculture Department programs and by cutting about $8 billion in food stamp assistance.”

Okay, how big a deal is savings $8 billion on food stamps over the next five years or $23 billion on the whole bill? Sure, everyone knows the significance of these numbers because they’ve been reading through the Office of Management and Budget’s projection for the next decade.

This is just asinine. The Post’s reporters and editors know that almost none of their readers have any sense of what these numbers mean in terms of the total budget or their own pocket book. They are just really big numbers, as David Leonhardt the former Washington editor of the NYT said. Since almost no one reading these numbers can attach any meaning to them, the purpose of putting them in the paper cannot be to inform readers. Obviously the motive here is to comply with the bizarre fraternity ritual of budget reporters.

It is not hard to express these numbers in ways that would convey information to the vast majority of readers. A quick trip to CEPR’s Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator would tell readers that the $23 billion cut amounts to 0.11 percent of projected federal spending while the $8 billion cut in food stamps would reduce federal spending by 0.04 percent. Now you know how much consequence these items have for the budget and your tax bill. Maybe one day we will have reporters and news outlets that put informing their audience above fraternity rituals, but not this day.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The story of the housing bubble and the impact of its bursting is pretty damn simple. If we go back to the bubble years, 2002-2007, the housing market was driving the economy. It was doing this both directly as construction spending peaked at close to 6.5 percent of GDP, two percentage points above its average over the prior two decades. It also drove consumption as people spent based on the equity in their home created by the bubble. The savings rate fell to almost zero based on this housing wealth effect.

When the bubble burst, we had nothing to replace the lost demand. Housing construction fell to well below normal levels in response to the huge overbuilding of the bubble years. At the trough construction was down by more than 4.0 percentage points of GDP or $660 billion a year in today’s economy. Consumption also fell as the home equity that was driving it disappeared. If we assume a housing wealth effect of 5-7 percent (i.e. a dollar of housing wealth increases annual consumption by 5-7 cents) then the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth would correspond to a reduction in annual consumption of between $400 billion and $560 billion. Taken together, the loss of construction and consumption spending imply a loss in annual demand of more than $1 trillion.

That’s the basic story, unfortunately it is far too simple for most analysts to understand. Hence we have Robert Samuelson bemoaning the fact that the Fed wasn’t able to instill the confidence to get businesses to invest and consumers to spend. The problem with the Samuelson story is that its basic facts are wrong.

Non-residential investment is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. Given the weak demand in the economy, this is very impressive. It certainly doesn’t give any evidence of a lack of confidence. And consumers are spending. The savings rate is now below 5.0 percent of GDP. This compares to a pre-stock and housing bubble average of more than 10.0 percent of GDP. The only time that the saving rate has been lower has been at the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles. In short, Samuelson is looking for an explanation for weaknesses in spending that do not exist.

The need for additional demand stems primarily from the trade deficit. This creates a gap in demand of roughly 3.0 percent of GDP, which would be closer to 4.0 percent of GDP if we were at full employment. For some reason, Samuelson doesn’t discuss this issue, perhaps because he doesn’t have access to the data.

(Reports are that Ezra Klein left the Post because it’s so hard to get government data there.)

The story of the housing bubble and the impact of its bursting is pretty damn simple. If we go back to the bubble years, 2002-2007, the housing market was driving the economy. It was doing this both directly as construction spending peaked at close to 6.5 percent of GDP, two percentage points above its average over the prior two decades. It also drove consumption as people spent based on the equity in their home created by the bubble. The savings rate fell to almost zero based on this housing wealth effect.

When the bubble burst, we had nothing to replace the lost demand. Housing construction fell to well below normal levels in response to the huge overbuilding of the bubble years. At the trough construction was down by more than 4.0 percentage points of GDP or $660 billion a year in today’s economy. Consumption also fell as the home equity that was driving it disappeared. If we assume a housing wealth effect of 5-7 percent (i.e. a dollar of housing wealth increases annual consumption by 5-7 cents) then the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth would correspond to a reduction in annual consumption of between $400 billion and $560 billion. Taken together, the loss of construction and consumption spending imply a loss in annual demand of more than $1 trillion.

That’s the basic story, unfortunately it is far too simple for most analysts to understand. Hence we have Robert Samuelson bemoaning the fact that the Fed wasn’t able to instill the confidence to get businesses to invest and consumers to spend. The problem with the Samuelson story is that its basic facts are wrong.

Non-residential investment is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. Given the weak demand in the economy, this is very impressive. It certainly doesn’t give any evidence of a lack of confidence. And consumers are spending. The savings rate is now below 5.0 percent of GDP. This compares to a pre-stock and housing bubble average of more than 10.0 percent of GDP. The only time that the saving rate has been lower has been at the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles. In short, Samuelson is looking for an explanation for weaknesses in spending that do not exist.

The need for additional demand stems primarily from the trade deficit. This creates a gap in demand of roughly 3.0 percent of GDP, which would be closer to 4.0 percent of GDP if we were at full employment. For some reason, Samuelson doesn’t discuss this issue, perhaps because he doesn’t have access to the data.

(Reports are that Ezra Klein left the Post because it’s so hard to get government data there.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steven Rattner took up large chunks of the NYT opinion section to express confused thoughts on manufacturing. Rattner sorts of meanders everywhere and back. The government should help manufacturing, but not like Solyndra and Fisker. Right, we don’t want help the losers, we just want to help all the companies that got loans and were successful. Does Rattner want to tell us how we would determine in advance which ones those will be?

We want better education. Sure, that’s great, any ideas on how we should do that?

It’s hardly worth going through all the silliness in Rattner’s piece, rather I will just mention the incredible bottom line. Rattner never once mentions the value of the dollar. This happens to be huge. If Rattner has access to government data he would know that manufacturing employment first began to fall in the late 1990s, even as the economy was booming, after the dollar soared due to the botched bailout from the East Asian financial crisis. The run-up in the dollar had the equivalent effect of placing a 30 percent tariff on our exports and giving a 30 percent subsidy for imports. Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that manufacturing employment fell and the trade deficit soared.

Rattner’s confusion about trade and the value of the dollar extends to his endorsement of new “trade” deals. Of course agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade barriers, they are about imposing corporate friendly regulations on the U.S. and our trading partners.

Among the top priority for U.S. negotiators is increasing the strength of patent protection for prescription drugs. Insofar as they succeed it will mean that foreigners will have to pay more money to Pfizer and Merck, which means that they will have less money to buy U.S. manufactured goods. That is hurting, not helping U.S. manufacturing . That one should be simple enough even for Steven Rattner to understand.

Steven Rattner took up large chunks of the NYT opinion section to express confused thoughts on manufacturing. Rattner sorts of meanders everywhere and back. The government should help manufacturing, but not like Solyndra and Fisker. Right, we don’t want help the losers, we just want to help all the companies that got loans and were successful. Does Rattner want to tell us how we would determine in advance which ones those will be?

We want better education. Sure, that’s great, any ideas on how we should do that?

It’s hardly worth going through all the silliness in Rattner’s piece, rather I will just mention the incredible bottom line. Rattner never once mentions the value of the dollar. This happens to be huge. If Rattner has access to government data he would know that manufacturing employment first began to fall in the late 1990s, even as the economy was booming, after the dollar soared due to the botched bailout from the East Asian financial crisis. The run-up in the dollar had the equivalent effect of placing a 30 percent tariff on our exports and giving a 30 percent subsidy for imports. Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that manufacturing employment fell and the trade deficit soared.

Rattner’s confusion about trade and the value of the dollar extends to his endorsement of new “trade” deals. Of course agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade barriers, they are about imposing corporate friendly regulations on the U.S. and our trading partners.

Among the top priority for U.S. negotiators is increasing the strength of patent protection for prescription drugs. Insofar as they succeed it will mean that foreigners will have to pay more money to Pfizer and Merck, which means that they will have less money to buy U.S. manufactured goods. That is hurting, not helping U.S. manufacturing . That one should be simple enough even for Steven Rattner to understand.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

One of the reasons that the housing bubble caught so many people by surprise was that the media relied largely on people who had an interest in pushing housing as their sources in reporting. This still seems to be the case today as indicated by a NYT piece on the housing market.

At one point the piece cites economist Mark Zandi, telling readers:

“Tighter lending standards are shutting out close to 12.5 million consumers who would qualify in normal times.”

It’s difficult to attach any meaning to this statement. We currently have 75 million home owning households and 40 million renting households. Is Zandi saying that among the 40 million renting households we have 12.5 million people who would in other times qualify for mortgages but do not today? Many renters do now qualify for a mortgage. If we say that a quarter of renters could now buy a home if they wanted, then Zandi’s claim would be that 12.5 million of the 30 million remaining renters (42 percent) would in normal times be able to get mortgages but are unable to do so because of tight credit conditions today. That one is a bit hard to believe. (It’s possible that the number includes people who can’t refinance because they have little or no equity in their home, but that is a very different issue.)

In the same vein, the piece tells readers:

“Mortgages are roughly seven times harder to get than they were five years ago, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s credit availability index, and they show few signs of getting easier.”

The seven times harder refers to an index that the Mortgage Bankers Association constructed that is at one seventh of its value five years ago. It doesn’t mean that a person has one seventh the chance of getting a mortgage.

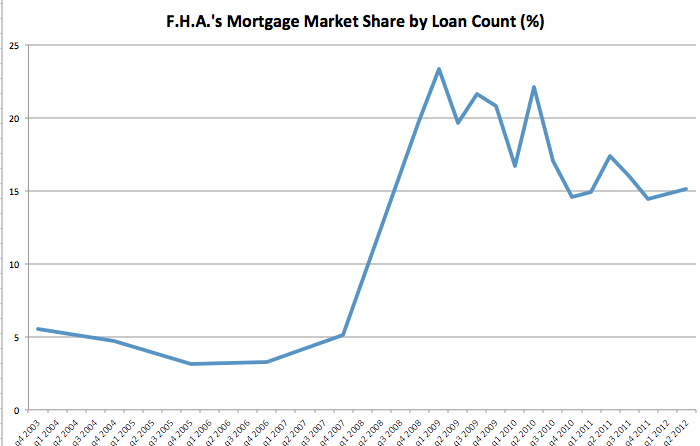

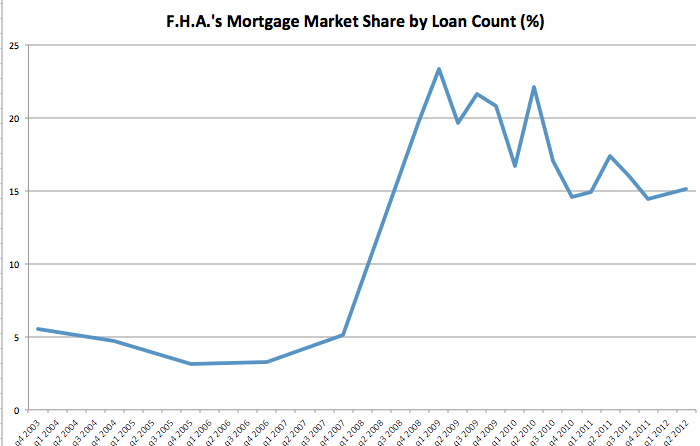

Incredibly this piece never mentions the role of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). While the FHA virtually disappeared as a factor in the housing market at the peak of the housing boom, because it did not relax its standards, its role hugely expanded after the crash. When the housing market was bottoming out in 2009 and 2010 it guaranteed more than 20 percent of new mortgages. It still insures close to 15 percent. Many people who would not meet the standards for a Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac mortgages can get one insured by the FHA.

Source: Business Insider/HUD.

One of the reasons that the housing bubble caught so many people by surprise was that the media relied largely on people who had an interest in pushing housing as their sources in reporting. This still seems to be the case today as indicated by a NYT piece on the housing market.

At one point the piece cites economist Mark Zandi, telling readers:

“Tighter lending standards are shutting out close to 12.5 million consumers who would qualify in normal times.”

It’s difficult to attach any meaning to this statement. We currently have 75 million home owning households and 40 million renting households. Is Zandi saying that among the 40 million renting households we have 12.5 million people who would in other times qualify for mortgages but do not today? Many renters do now qualify for a mortgage. If we say that a quarter of renters could now buy a home if they wanted, then Zandi’s claim would be that 12.5 million of the 30 million remaining renters (42 percent) would in normal times be able to get mortgages but are unable to do so because of tight credit conditions today. That one is a bit hard to believe. (It’s possible that the number includes people who can’t refinance because they have little or no equity in their home, but that is a very different issue.)

In the same vein, the piece tells readers:

“Mortgages are roughly seven times harder to get than they were five years ago, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s credit availability index, and they show few signs of getting easier.”

The seven times harder refers to an index that the Mortgage Bankers Association constructed that is at one seventh of its value five years ago. It doesn’t mean that a person has one seventh the chance of getting a mortgage.

Incredibly this piece never mentions the role of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). While the FHA virtually disappeared as a factor in the housing market at the peak of the housing boom, because it did not relax its standards, its role hugely expanded after the crash. When the housing market was bottoming out in 2009 and 2010 it guaranteed more than 20 percent of new mortgages. It still insures close to 15 percent. Many people who would not meet the standards for a Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac mortgages can get one insured by the FHA.

Source: Business Insider/HUD.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

All Things Considered ran a piece making the obvious point, it doesn’t matter for the finances of the health insurance exchanges whether or not young people sign up. What matters is that healthy people sign up. Some of us have been making this point for a while, but it’s great to see that major national news outlets are capable of learning.

All Things Considered ran a piece making the obvious point, it doesn’t matter for the finances of the health insurance exchanges whether or not young people sign up. What matters is that healthy people sign up. Some of us have been making this point for a while, but it’s great to see that major national news outlets are capable of learning.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión