Some strange items got into the coverage of the December employment report. The Washington Post noted the weak job numbers and then told readers:

“The unemployment rate dropped to 6.7 percent, but mostly because many people gave up looking for work, possibly deterred by a combination of cold weather, the holiday season and the expiration of long-term unemployment benefits. (To qualify for the benefit, an applicant must be trying to find a job.)”

The data are always seasonally adjusted. This means that cold weather would not by itself affect the data unless the weather was extraordinarily cold for December in large parts of the country. This was not the case. Similarly, the holiday season occurs every year in December, this cannot explain more people dropping out of the labor force this year than in prior years.

The ending of benefits is a plausible explanation, but not for December. One million three hundred thousand people saw their benefits expire on January 1, but this should not have affected their job searching behavior in December. At the time, they did not even know that their benefits would necessarily expire since bills for renewal were still being debated in Congress.

The NYT article on the report had the strange comment:

“In the larger political picture, the December jobs report started the 2014 election year with a thud for President Obama, with half of Americans disapproving of the job he is doing and Democrats facing a tough “six-year itch” election. Since World War II the party in the White House has lost, on average, 29 seats in the House in its second midterm. Democrats were already struggling to recover from the Affordable Care Act’s disastrous rollout.”

There will be 9 more jobs reports released between now and the November election. It is highly unlikely that any significant number of people’s votes in that election will be significantly affected by the December jobs report.

It is striking that neither report noticed that the labor force participation rate for African American men fell to the lowest level on record in the December report.

Some strange items got into the coverage of the December employment report. The Washington Post noted the weak job numbers and then told readers:

“The unemployment rate dropped to 6.7 percent, but mostly because many people gave up looking for work, possibly deterred by a combination of cold weather, the holiday season and the expiration of long-term unemployment benefits. (To qualify for the benefit, an applicant must be trying to find a job.)”

The data are always seasonally adjusted. This means that cold weather would not by itself affect the data unless the weather was extraordinarily cold for December in large parts of the country. This was not the case. Similarly, the holiday season occurs every year in December, this cannot explain more people dropping out of the labor force this year than in prior years.

The ending of benefits is a plausible explanation, but not for December. One million three hundred thousand people saw their benefits expire on January 1, but this should not have affected their job searching behavior in December. At the time, they did not even know that their benefits would necessarily expire since bills for renewal were still being debated in Congress.

The NYT article on the report had the strange comment:

“In the larger political picture, the December jobs report started the 2014 election year with a thud for President Obama, with half of Americans disapproving of the job he is doing and Democrats facing a tough “six-year itch” election. Since World War II the party in the White House has lost, on average, 29 seats in the House in its second midterm. Democrats were already struggling to recover from the Affordable Care Act’s disastrous rollout.”

There will be 9 more jobs reports released between now and the November election. It is highly unlikely that any significant number of people’s votes in that election will be significantly affected by the December jobs report.

It is striking that neither report noticed that the labor force participation rate for African American men fell to the lowest level on record in the December report.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Brad Plummer reports on a study from the Urban Institute which purports to explain the drop in labor force participation as a story of fewer people entering the workforce after a period of being out of the workforce, as opposed to more people leaving. This explanation actually is not supported by the results shown in the study.

The study finds only a very slight falloff in the entry rate for prime age men (Table 2), even though there has been a sharp falloff in their labor force participation rate. On the other hand it shows the sharpest declines in entry for older workers, who in fact have seen a decline in labor force participation. This suggests that the study’s sample is not reflecting larger labor force conditions. (The study uses the Survey on Income and Program Participation, which has a considerably smaller sample size that the Current Population Survey that is conventionally used for labor market analysis. There is likely also a problem with people dropping out of the survey, who are likely to be a particularly large share of those dropping out of the labor force.)

It’s also worth noting that their analysis only looked at the falloff in labor force participation rate in one year, from 2010 to 2011. In that year we saw a drop 0.6 percentage points of a total falloff of 2.1 percentage points for prime age women and 0.7 percentage points of a total falloff of 3.4 percentage points for prime age men.

Brad Plummer reports on a study from the Urban Institute which purports to explain the drop in labor force participation as a story of fewer people entering the workforce after a period of being out of the workforce, as opposed to more people leaving. This explanation actually is not supported by the results shown in the study.

The study finds only a very slight falloff in the entry rate for prime age men (Table 2), even though there has been a sharp falloff in their labor force participation rate. On the other hand it shows the sharpest declines in entry for older workers, who in fact have seen a decline in labor force participation. This suggests that the study’s sample is not reflecting larger labor force conditions. (The study uses the Survey on Income and Program Participation, which has a considerably smaller sample size that the Current Population Survey that is conventionally used for labor market analysis. There is likely also a problem with people dropping out of the survey, who are likely to be a particularly large share of those dropping out of the labor force.)

It’s also worth noting that their analysis only looked at the falloff in labor force participation rate in one year, from 2010 to 2011. In that year we saw a drop 0.6 percentage points of a total falloff of 2.1 percentage points for prime age women and 0.7 percentage points of a total falloff of 3.4 percentage points for prime age men.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece touting the improvement in the state of the economy. It notes that many economists now expect the economy to grow at close to a 3.0 percent annual rate in 2014. While this is considerably better than the growth rate over the prior four years, it is not an especially strong growth rate for a badly depressed economy.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the economy is still operating at a level of output that is roughly 6.0 percent below its potential. With potential GDP growing at a 2.2-2.4 percent annual rate, a 3.0 percent growth rate means that we are making up this gap at the rate of 0.6-0.8 percentage points a year. At this pace it would between 7.5-10.0 years to get back to potential GDP.

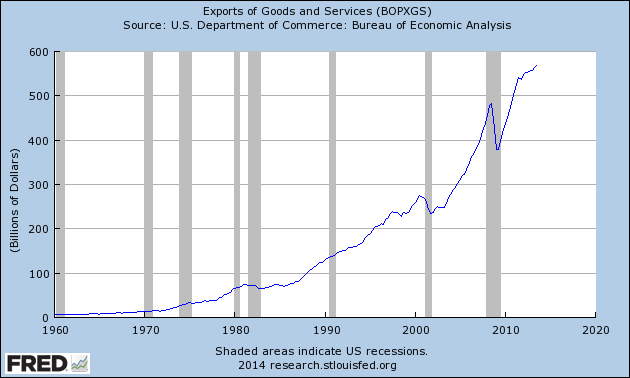

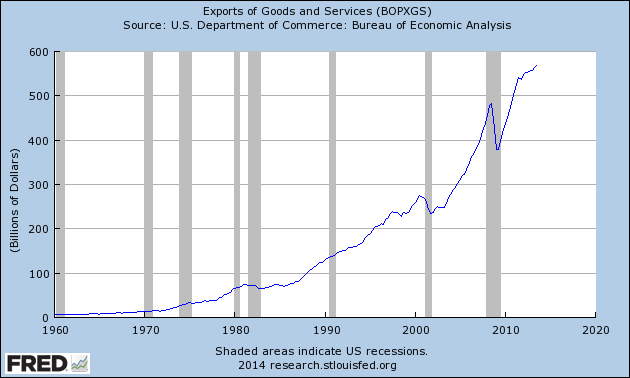

The piece also begins by noting that exports hit a new record high in the most recent data. Actually exports generally grow, except in a severe world slump like the 2008 crash. For this reason exports almost always hit a new record high every month.

The NYT had a piece touting the improvement in the state of the economy. It notes that many economists now expect the economy to grow at close to a 3.0 percent annual rate in 2014. While this is considerably better than the growth rate over the prior four years, it is not an especially strong growth rate for a badly depressed economy.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the economy is still operating at a level of output that is roughly 6.0 percent below its potential. With potential GDP growing at a 2.2-2.4 percent annual rate, a 3.0 percent growth rate means that we are making up this gap at the rate of 0.6-0.8 percentage points a year. At this pace it would between 7.5-10.0 years to get back to potential GDP.

The piece also begins by noting that exports hit a new record high in the most recent data. Actually exports generally grow, except in a severe world slump like the 2008 crash. For this reason exports almost always hit a new record high every month.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Michael Gerson tells readers:

“The tie between single-parent households and poverty is an economic, not a moral, assertion. Poor single parents naturally find it harder to hold full-time jobs and invest in the welfare of their children.”

While this is true, it does not follow that the answer is to somehow force couples to stay together in bad and possibly abusive relationships, as Gerson seems to imply. The difficulty faced by children in single-parent families can be seen as a problem of adequate supports in the form of affordable child care or guarantees of paid time off for sick days and family leave. In other countries where such support does exist, children in single-parent families do not face nearly the same handicap as they do in the United States. (See Shawn Fremstad’s discussion here and here.)

The other key pillars in Gerson’s argument about poverty also don’t stand up well to the facts.

“This is a type of poverty that Johnson could not foresee: a decline in blue-collar jobs, rooted in global trends, requiring workers to gain skills that schools could not reliably impart, leaving whole communities economically depressed and isolated, while many children were deprived of economically stable and supportive two-parent families, leading to dangerously stalled social mobility and creating divisions of class that are inconsistent with the American ideal.”

Globalization did not just happen. There was a conscious decision to put manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, while largely protecting highly paid professionals like doctors and lawyers. This had the predicted effect of redistributing income upward. There also is little evidence that technology has had more impact in displacing less educated workers in the last three decades than in prior decades.

Michael Gerson tells readers:

“The tie between single-parent households and poverty is an economic, not a moral, assertion. Poor single parents naturally find it harder to hold full-time jobs and invest in the welfare of their children.”

While this is true, it does not follow that the answer is to somehow force couples to stay together in bad and possibly abusive relationships, as Gerson seems to imply. The difficulty faced by children in single-parent families can be seen as a problem of adequate supports in the form of affordable child care or guarantees of paid time off for sick days and family leave. In other countries where such support does exist, children in single-parent families do not face nearly the same handicap as they do in the United States. (See Shawn Fremstad’s discussion here and here.)

The other key pillars in Gerson’s argument about poverty also don’t stand up well to the facts.

“This is a type of poverty that Johnson could not foresee: a decline in blue-collar jobs, rooted in global trends, requiring workers to gain skills that schools could not reliably impart, leaving whole communities economically depressed and isolated, while many children were deprived of economically stable and supportive two-parent families, leading to dangerously stalled social mobility and creating divisions of class that are inconsistent with the American ideal.”

Globalization did not just happen. There was a conscious decision to put manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, while largely protecting highly paid professionals like doctors and lawyers. This had the predicted effect of redistributing income upward. There also is little evidence that technology has had more impact in displacing less educated workers in the last three decades than in prior decades.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s Novartis and Japan today. The NYT reports on allegations that the company altered test results to exaggerate the effectiveness of Diovan, a drug for treating high blood pressure and heart disease. This is the sort of corruption that economic theory predicts would result from government granted patent monopolies. By raising the price of drugs by several thousand percent above their free market price, patents provide an enormous incentive for drug companies to misrepresent the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

It’s Novartis and Japan today. The NYT reports on allegations that the company altered test results to exaggerate the effectiveness of Diovan, a drug for treating high blood pressure and heart disease. This is the sort of corruption that economic theory predicts would result from government granted patent monopolies. By raising the price of drugs by several thousand percent above their free market price, patents provide an enormous incentive for drug companies to misrepresent the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Most of us see politicians getting their jobs by appealing to individuals and interest groups with money and power. That might lead us to believe that the major political battles are over who gets the money. But the Washington Post says we’re wrong. Really the big battles are over philosophy.

I’m not kidding, it’s right there in the headline:

“‘great society’ agenda led to great — and lasting — philosophical divide.”

The piece repeatedly asserts that major battles over public issues are matters of philosophy about the role of government. While that may contradict the understanding that most people have of politics, it is a useful argument for the wealthy. If people understood the debates over policy issues as being debate over whether the rich or everyone else would get money, the rich would likely lose in democratic elections, since they are hugely outnumbered.

However, if the debate can be framed as a matter of philosophy, then the rich stand a much better chance. They can hire people to argue their “philosophy” in television, newspapers, and other media forums.

As a practical matter it is easy to show that the rich have no objection to a big role for government in the economy. For example, they strongly support government granted patent monopolies for prescription drugs. These monopolies redistribute around $270 billion a year (1.6 percent of GDP) from patients to drug companies. This is more than three times as much money as is paid in food stamp benefits each year and more than ten times the amount of money at stake with extending unemployment benefits.

There are many other examples of major government interventions in the economy that have the full support of the rich. However, they are clever enough to try to hide these interventions in order to preserve the guise of supporting “free markets.” They can usually count on the cooperation of major media outlets in maintaining this fiction. (Yes, this is the topic of my book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

Most of us see politicians getting their jobs by appealing to individuals and interest groups with money and power. That might lead us to believe that the major political battles are over who gets the money. But the Washington Post says we’re wrong. Really the big battles are over philosophy.

I’m not kidding, it’s right there in the headline:

“‘great society’ agenda led to great — and lasting — philosophical divide.”

The piece repeatedly asserts that major battles over public issues are matters of philosophy about the role of government. While that may contradict the understanding that most people have of politics, it is a useful argument for the wealthy. If people understood the debates over policy issues as being debate over whether the rich or everyone else would get money, the rich would likely lose in democratic elections, since they are hugely outnumbered.

However, if the debate can be framed as a matter of philosophy, then the rich stand a much better chance. They can hire people to argue their “philosophy” in television, newspapers, and other media forums.

As a practical matter it is easy to show that the rich have no objection to a big role for government in the economy. For example, they strongly support government granted patent monopolies for prescription drugs. These monopolies redistribute around $270 billion a year (1.6 percent of GDP) from patients to drug companies. This is more than three times as much money as is paid in food stamp benefits each year and more than ten times the amount of money at stake with extending unemployment benefits.

There are many other examples of major government interventions in the economy that have the full support of the rich. However, they are clever enough to try to hide these interventions in order to preserve the guise of supporting “free markets.” They can usually count on the cooperation of major media outlets in maintaining this fiction. (Yes, this is the topic of my book, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post dives into the really big numbers game today telling readers about a compromise between Democrats and Republicans in Congress that will lead to $9 billion in cuts to the food stamp program over the next decade. If you’re expecting a big tax cut from eliminating this spending on food stamps, you might want to wait a bit before spending the windfall.

If we go CEPR’s nifty responsible budget reporting calculator we find that this cut comes to 0.019 percent of federal spending over this period. In other words, the cuts may mean a lot to the people affected. They don’t mean much to the overall budget. (But hey, Washington Post readers knew that, right?)

The Washington Post dives into the really big numbers game today telling readers about a compromise between Democrats and Republicans in Congress that will lead to $9 billion in cuts to the food stamp program over the next decade. If you’re expecting a big tax cut from eliminating this spending on food stamps, you might want to wait a bit before spending the windfall.

If we go CEPR’s nifty responsible budget reporting calculator we find that this cut comes to 0.019 percent of federal spending over this period. In other words, the cuts may mean a lot to the people affected. They don’t mean much to the overall budget. (But hey, Washington Post readers knew that, right?)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Those who hoped to be informed about the state of the economy by reading this NYT piece on President Obama’s renewed focus on the economy made a bad mistake. The piece implies that the economy is largely back to normal except for pockets of people who have been left behind. For example it tells readers:

“He is presiding over an economy that has improved sharply in the five years since 2009, when it was buckling under the weight of a severe recession, but decades-long shifts in technology and globalization have left more people out of work for extended periods than at any other time in the past 50 years.’

The piece then adds:

“Like Mr. Obama, President Ronald Reagan also ended his fifth year with unemployment at 7 percent after a devastating recession. But Mr. Reagan was sunnier in public as the country’s financial fortunes turned around, and ran for re-election in 1984 with an advertising campaign that declared ‘It’s morning again in America’ for a country weary of economic distress. Mr. Obama has chosen to be more restrained in his enthusiasm.”

It is not just a question of sunny disposition. By the beginning of 1986 the economy had 7.8 percent more jobs than it had in its pre-recession peak in July of 1981. By contrast, the number of jobs is still 1.0 percent below its pre-recession peak in January of 2008. The same story can be seen looking at the ratio of employment to population (EPOP). In January of 1986 the EPOP was 0.6 percentage points above its pre-recession peak. By contrast the EPOP is now more than 4.5 percentage points below its pre-recession peak. This corresponds to more than 10 million fewer people working. By any reasonable measure the economy is in far worse shape today relative to its pre-recession level of output than it was in January 1986.

The assertion that people have been left out of work due to a “decades-long shifts in technology and globalization” is not supported by evidence. If there is reason to believe that most of the unemployed would not find work if the economy returned to its level of potential output (we are still down by more than 6 percent [$1 trillion annually] according to the Congressional Budget Office) the NYT opted not to show it.

In other words, the most obvious reason these people are unemployed is that the government is running macroeconomic policies that are keeping the economy far below its potential level of output, not some inexorable trend in globalization or technology. The latter view may absolve policy makers of blame for the plight of these people, as well as the lack of wage growth for the much larger group of people who are employed but not sharing in the economy’s growth, but it is far from obvious that it correctly describes the economy. It is irresponsible of the NYT to just assert it as fact.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Those who hoped to be informed about the state of the economy by reading this NYT piece on President Obama’s renewed focus on the economy made a bad mistake. The piece implies that the economy is largely back to normal except for pockets of people who have been left behind. For example it tells readers:

“He is presiding over an economy that has improved sharply in the five years since 2009, when it was buckling under the weight of a severe recession, but decades-long shifts in technology and globalization have left more people out of work for extended periods than at any other time in the past 50 years.’

The piece then adds:

“Like Mr. Obama, President Ronald Reagan also ended his fifth year with unemployment at 7 percent after a devastating recession. But Mr. Reagan was sunnier in public as the country’s financial fortunes turned around, and ran for re-election in 1984 with an advertising campaign that declared ‘It’s morning again in America’ for a country weary of economic distress. Mr. Obama has chosen to be more restrained in his enthusiasm.”

It is not just a question of sunny disposition. By the beginning of 1986 the economy had 7.8 percent more jobs than it had in its pre-recession peak in July of 1981. By contrast, the number of jobs is still 1.0 percent below its pre-recession peak in January of 2008. The same story can be seen looking at the ratio of employment to population (EPOP). In January of 1986 the EPOP was 0.6 percentage points above its pre-recession peak. By contrast the EPOP is now more than 4.5 percentage points below its pre-recession peak. This corresponds to more than 10 million fewer people working. By any reasonable measure the economy is in far worse shape today relative to its pre-recession level of output than it was in January 1986.

The assertion that people have been left out of work due to a “decades-long shifts in technology and globalization” is not supported by evidence. If there is reason to believe that most of the unemployed would not find work if the economy returned to its level of potential output (we are still down by more than 6 percent [$1 trillion annually] according to the Congressional Budget Office) the NYT opted not to show it.

In other words, the most obvious reason these people are unemployed is that the government is running macroeconomic policies that are keeping the economy far below its potential level of output, not some inexorable trend in globalization or technology. The latter view may absolve policy makers of blame for the plight of these people, as well as the lack of wage growth for the much larger group of people who are employed but not sharing in the economy’s growth, but it is far from obvious that it correctly describes the economy. It is irresponsible of the NYT to just assert it as fact.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Robert Salzberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When someone touts the risks of deflation it is simply their way of saying that they don’t understand the economy. The NYT provided us this service in an article on how the euro zone is seeing a lower than desired rate of inflation.

After noting that year over year inflation was just 0.8 percent in the most recent data, well below the European Central Bank’s 2.0 percent target, the article tells readers:

“Europe could face outright deflation — a debilitating economic condition in which prices actually decline across the board.

“As long as hints of deflation remain, the E.C.B. faces a difficult challenge.”

It later adds:

“Spain’s consumer prices rose just 0.3 percent, while Italy’s rose only 0.2 percent, as those two countries’ troubled economies teetered near a deflationary cliff.

“Deflation would only add to the broader economic malaise in the region, by hurting corporate profits and by leading consumers to delay purchases in anticipation of better deals in the future. It would also weigh heavily on borrowers, making loan repayments more expensive in real terms — a particular danger for Europe’s already fragile financial sector.”

Okay, let’s get this straight. It’s okay if the inflation rate is 0.2 percent or 0.3 percent, but all hell breaks loose if we are looking at 0.5 percent deflation? How does that work?

The article tells us corporate profits will be lower. Well, ignoring the fact that corporate profits are currently very high, how does a dip from 0.3 percent inflation to 0.5 percent deflation affect corporate profits in a way that is different from a dip from 1.1 percent inflation to 0.3 percent inflation? If the inflation rate is lower than what businesses had expected then they will be selling their output for a lower than expected price. That means lower profits regardless of whether or not the lower inflation rate is positive to negative.

As far as consumers delaying purchases, let’s try some arithmetic. Suppose someone is considering a big ticket item like a television or a refrigerator that costs $1,000. If the rate of deflation is 0.5 percent, our would-be buyer would save $2.50 by delaying their purchase for six months. They would get a $5 windfall if they delay the purchase a full year. Is this going to be a big problem?

To make matters worse for the deflation hawks, many prices are already falling even before we fall off the “deflationary cliff.” The overall inflation rate is an average of millions of price changes. When the average is positive but close to zero then it is inevitable that the price of many items is already falling. Is that a big problem? Well, the price of computers has been falling sharply for decades.

The real issue here is simple. It would be desirable to have a lower real interest rate in the euro zone to boost demand. This can only be brought about with a higher rate of inflation. It would also be helpful to have higher inflation in core countries like Germany so that peripheral countries like Spain and Greece can regain competitiveness within the euro zone. Going from a positive rate of inflation to deflation is a move in the wrong direction, but it is not qualitatively different from a drop in the rate of inflation to a still positive rate. The problem is simply too low a rate of inflation, there is nothing magical about crossing zero. (As a practical matter, there is enough measurement error in price indices that a low reported positive rate is in fact consistent with a true negative rate.)

When someone touts the risks of deflation it is simply their way of saying that they don’t understand the economy. The NYT provided us this service in an article on how the euro zone is seeing a lower than desired rate of inflation.

After noting that year over year inflation was just 0.8 percent in the most recent data, well below the European Central Bank’s 2.0 percent target, the article tells readers:

“Europe could face outright deflation — a debilitating economic condition in which prices actually decline across the board.

“As long as hints of deflation remain, the E.C.B. faces a difficult challenge.”

It later adds:

“Spain’s consumer prices rose just 0.3 percent, while Italy’s rose only 0.2 percent, as those two countries’ troubled economies teetered near a deflationary cliff.

“Deflation would only add to the broader economic malaise in the region, by hurting corporate profits and by leading consumers to delay purchases in anticipation of better deals in the future. It would also weigh heavily on borrowers, making loan repayments more expensive in real terms — a particular danger for Europe’s already fragile financial sector.”

Okay, let’s get this straight. It’s okay if the inflation rate is 0.2 percent or 0.3 percent, but all hell breaks loose if we are looking at 0.5 percent deflation? How does that work?

The article tells us corporate profits will be lower. Well, ignoring the fact that corporate profits are currently very high, how does a dip from 0.3 percent inflation to 0.5 percent deflation affect corporate profits in a way that is different from a dip from 1.1 percent inflation to 0.3 percent inflation? If the inflation rate is lower than what businesses had expected then they will be selling their output for a lower than expected price. That means lower profits regardless of whether or not the lower inflation rate is positive to negative.

As far as consumers delaying purchases, let’s try some arithmetic. Suppose someone is considering a big ticket item like a television or a refrigerator that costs $1,000. If the rate of deflation is 0.5 percent, our would-be buyer would save $2.50 by delaying their purchase for six months. They would get a $5 windfall if they delay the purchase a full year. Is this going to be a big problem?

To make matters worse for the deflation hawks, many prices are already falling even before we fall off the “deflationary cliff.” The overall inflation rate is an average of millions of price changes. When the average is positive but close to zero then it is inevitable that the price of many items is already falling. Is that a big problem? Well, the price of computers has been falling sharply for decades.

The real issue here is simple. It would be desirable to have a lower real interest rate in the euro zone to boost demand. This can only be brought about with a higher rate of inflation. It would also be helpful to have higher inflation in core countries like Germany so that peripheral countries like Spain and Greece can regain competitiveness within the euro zone. Going from a positive rate of inflation to deflation is a move in the wrong direction, but it is not qualitatively different from a drop in the rate of inflation to a still positive rate. The problem is simply too low a rate of inflation, there is nothing magical about crossing zero. (As a practical matter, there is enough measurement error in price indices that a low reported positive rate is in fact consistent with a true negative rate.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As we mark the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty, it would be appropriate to note one of the main causes of its limited success, using big numbers without context. The issue here is a simple one; most people think that we have committed vastly more resources than is in fact the case to fighting this war. As a result, they are reasonably (based on their understanding) reluctant to contribute more resources.

Polls consistently show the public hugely exaggerates the share of the budget that goes to programs like Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) or food stamps. They believe that these anti-poverty programs are responsible for a large share of the budget when in reality their impact is marginal. (TANF accounts for about 0.4 percent of federal spending and food stamps account for 2.1 percent.) This is partly due to the fact that these items are always reported as millions or billions of dollars, which are very large numbers that few people can conceptualize. They are rarely reported as shares of the total budget.

As a result of exaggerating their importance to the budget, the public is less likely to support anti-poverty programs. They see them as a big part of their tax bill, thinking that their taxes, or at least the deficit, would decrease substantially if we spent less on these programs.

They also reasonably question their effectiveness. If we were actually spending one-third of the budget on anti-poverty programs and still had so many poor people, then the public would be right to question whether this was a good use of their tax dollars.

The NYT has committed itself to expressing large budget numbers in a context that will make them understandable to readers. It remains to be seen whether they will follow through on this commitment. If they do, and the rest of the media follow suit, it will have a substantial impact on the public’s understanding of the War on Poverty.

As we mark the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty, it would be appropriate to note one of the main causes of its limited success, using big numbers without context. The issue here is a simple one; most people think that we have committed vastly more resources than is in fact the case to fighting this war. As a result, they are reasonably (based on their understanding) reluctant to contribute more resources.

Polls consistently show the public hugely exaggerates the share of the budget that goes to programs like Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) or food stamps. They believe that these anti-poverty programs are responsible for a large share of the budget when in reality their impact is marginal. (TANF accounts for about 0.4 percent of federal spending and food stamps account for 2.1 percent.) This is partly due to the fact that these items are always reported as millions or billions of dollars, which are very large numbers that few people can conceptualize. They are rarely reported as shares of the total budget.

As a result of exaggerating their importance to the budget, the public is less likely to support anti-poverty programs. They see them as a big part of their tax bill, thinking that their taxes, or at least the deficit, would decrease substantially if we spent less on these programs.

They also reasonably question their effectiveness. If we were actually spending one-third of the budget on anti-poverty programs and still had so many poor people, then the public would be right to question whether this was a good use of their tax dollars.

The NYT has committed itself to expressing large budget numbers in a context that will make them understandable to readers. It remains to be seen whether they will follow through on this commitment. If they do, and the rest of the media follow suit, it will have a substantial impact on the public’s understanding of the War on Poverty.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión