I can’t find a doctor to work for me for $30 an hour. According to the NYT this would mean that the United States has a doctor shortage. That appears to be the logic of a major article asserting that Europe’s economy is suffering from a shortage of skilled workers even as its unemployment rate is near 12 percent.

The piece never once mentions the trends in wages for workers with the skills that are allegedly in short supply. As a practical matter, there has been a shift from wages to profits over the last three decades which accelerated with the downturn. In the United States, which also supposedly suffers from a skills shortage, even workers with degrees in science, math, and engineering, are not seeing their wages keep pace with economy-wide productivity growth.

It is understandable that employers will always want lower cost labor just as most of us would be happy to save money by having qualified doctors work for us at $30 an hour. However the desire of companies to increase profits further doesn’t mean there is a shortage of skilled workers anymore than the lack of doctors willing to work for $30 an hour implies a shortage of doctors.

I can’t find a doctor to work for me for $30 an hour. According to the NYT this would mean that the United States has a doctor shortage. That appears to be the logic of a major article asserting that Europe’s economy is suffering from a shortage of skilled workers even as its unemployment rate is near 12 percent.

The piece never once mentions the trends in wages for workers with the skills that are allegedly in short supply. As a practical matter, there has been a shift from wages to profits over the last three decades which accelerated with the downturn. In the United States, which also supposedly suffers from a skills shortage, even workers with degrees in science, math, and engineering, are not seeing their wages keep pace with economy-wide productivity growth.

It is understandable that employers will always want lower cost labor just as most of us would be happy to save money by having qualified doctors work for us at $30 an hour. However the desire of companies to increase profits further doesn’t mean there is a shortage of skilled workers anymore than the lack of doctors willing to work for $30 an hour implies a shortage of doctors.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Uwe Reinhardt has a useful blogpost taking issue with a Wall Street Journal editorial on the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The editorial had complained that the ACA steals $156 billion from the Medicare Advantage program, the portion of Medicare run by private insurers.

Reinhardt points out that this $156 billion in reduced payments is over a ten year period, a point missing from the editorial. That’s around 2.0 percent of projected Medicare spending over this period. The other key point in Reinhardt’s piece is that this reduction in payments for Medicare Advantage simply involves leveling the playing field so that the federal government will pay the same amount for each beneficiary in the Medicare Advantage program as in the traditional fee for service program.

Towards the end of the piece Reinhardt notes that, given the WSJ’s ideology, it is understandable that it would object to this leveling of the playing field. While this is true, this is not where a market oriented ideology would take them. If the WSJ editors were confident in the superiority of private sector insurers, they would not feel that they needed a subsidy compared with the traditional government program. The WSJ position only makes sense if the view of the editors is that it is the responsibility of government to redistribute money to the private insurers and implicitly their shareholders and top executives.

Uwe Reinhardt has a useful blogpost taking issue with a Wall Street Journal editorial on the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The editorial had complained that the ACA steals $156 billion from the Medicare Advantage program, the portion of Medicare run by private insurers.

Reinhardt points out that this $156 billion in reduced payments is over a ten year period, a point missing from the editorial. That’s around 2.0 percent of projected Medicare spending over this period. The other key point in Reinhardt’s piece is that this reduction in payments for Medicare Advantage simply involves leveling the playing field so that the federal government will pay the same amount for each beneficiary in the Medicare Advantage program as in the traditional fee for service program.

Towards the end of the piece Reinhardt notes that, given the WSJ’s ideology, it is understandable that it would object to this leveling of the playing field. While this is true, this is not where a market oriented ideology would take them. If the WSJ editors were confident in the superiority of private sector insurers, they would not feel that they needed a subsidy compared with the traditional government program. The WSJ position only makes sense if the view of the editors is that it is the responsibility of government to redistribute money to the private insurers and implicitly their shareholders and top executives.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Simon Johnson has a good post on how a bloated financial sector is often a curse to rich countries like the United States. The piece can use a small correction.

It gives South Korea as an example of a middle income country in which manufacturing still is a dominant force. South Korea really should be viewed as an advanced country. It’s per capita income is higher than Italy’s and only about 10 percent lower than the United Kingdom’s.

Simon Johnson has a good post on how a bloated financial sector is often a curse to rich countries like the United States. The piece can use a small correction.

It gives South Korea as an example of a middle income country in which manufacturing still is a dominant force. South Korea really should be viewed as an advanced country. It’s per capita income is higher than Italy’s and only about 10 percent lower than the United Kingdom’s.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Sarah Kliff has a useful discussion of the changes in the insurance market brought about by Obamacare. It points out that Obamacare will end discrimination based on pre-existing conditions. While there will still be substantial differences in cost based on age, people will pay the same premiums regardless of their health.

However the piece is a bit misleading in its exclusive focus on the individual insurance market. The vast majority of the working age population gets insurance through their employer. With employer based insurance workers effectively pay the same for their insurance regardless of their health. (The premium paid by the employer is ultimately paid by the worker, since it comes out of wages. Employers don’t just give away insurance.)

This is important in the context of the debate around Obamacare since there has been considerable attention given the fact that the young to some extent subsidize the old, since the premium structure does not fully reflect the differences in average costs by age. Insofar as this cross-subsidy exists, Obamacare is just replicating a situation that has long been present in the much larger employer provided insurance system.

It is also worth noting that the subsidy from the healthy of all ages to the less healthy dwarfs the age-based subsidy. This is of course the purpose of the program: to make insurance affordable to the people who need it.

Sarah Kliff has a useful discussion of the changes in the insurance market brought about by Obamacare. It points out that Obamacare will end discrimination based on pre-existing conditions. While there will still be substantial differences in cost based on age, people will pay the same premiums regardless of their health.

However the piece is a bit misleading in its exclusive focus on the individual insurance market. The vast majority of the working age population gets insurance through their employer. With employer based insurance workers effectively pay the same for their insurance regardless of their health. (The premium paid by the employer is ultimately paid by the worker, since it comes out of wages. Employers don’t just give away insurance.)

This is important in the context of the debate around Obamacare since there has been considerable attention given the fact that the young to some extent subsidize the old, since the premium structure does not fully reflect the differences in average costs by age. Insofar as this cross-subsidy exists, Obamacare is just replicating a situation that has long been present in the much larger employer provided insurance system.

It is also worth noting that the subsidy from the healthy of all ages to the less healthy dwarfs the age-based subsidy. This is of course the purpose of the program: to make insurance affordable to the people who need it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is not exactly what he said, but that is what his comments in a Washington Post interview mean. Dimon said that the United States is suffering from a skills gap where firms can’t find workers with the skills they need. Dimon claimed that this skills shortage could be raising the unemployment rate by 1-2 percentage points.

In a market economy when there is a shortage of particular item, in this case skilled workers, the price is supposed to rise. There is no substantial sector of labor market seeing wages that are even keeping pace with overall productivity growth, much less rising due to shortages.

If firms really have slots going open because they can’t find workers with the skills they need then the problem is that we have employers who don’t understand how markets work. If they raised wages firms could attract skilled workers away from their competitors and more workers would try to acquire the necessary skills for their open positions. Perhaps if CEOs were required to take introductory economics courses we could solve this problem.

As a practical matter, we see no evidence to support Dimon’s assertion. There are no major occupational groupings with high ratios of vacancies to unemployed workers, nor do we see increases in the length of workweeks, which is another way that employers would deal with a shortage of skilled workers.

That is not exactly what he said, but that is what his comments in a Washington Post interview mean. Dimon said that the United States is suffering from a skills gap where firms can’t find workers with the skills they need. Dimon claimed that this skills shortage could be raising the unemployment rate by 1-2 percentage points.

In a market economy when there is a shortage of particular item, in this case skilled workers, the price is supposed to rise. There is no substantial sector of labor market seeing wages that are even keeping pace with overall productivity growth, much less rising due to shortages.

If firms really have slots going open because they can’t find workers with the skills they need then the problem is that we have employers who don’t understand how markets work. If they raised wages firms could attract skilled workers away from their competitors and more workers would try to acquire the necessary skills for their open positions. Perhaps if CEOs were required to take introductory economics courses we could solve this problem.

As a practical matter, we see no evidence to support Dimon’s assertion. There are no major occupational groupings with high ratios of vacancies to unemployed workers, nor do we see increases in the length of workweeks, which is another way that employers would deal with a shortage of skilled workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers of a Reuters article on complaints from a German business group must be asking themselves. At one point the article told readers:

“Major unions negotiated inflation-busting hikes in pay checks last year after years of wage restraint, although the Statistics Office said last month real wages across Germany were likely to have fallen in 2013.”

It’s not clear what the definition of “inflation-busting” is in this context, but it doesn’t sound like it involved large pay increases if wages did not even keep pace with inflation. Usually, they would be expected to rise somewhat in excess of inflation to reflect productivity growth in Germany’s economy.

That’s what readers of a Reuters article on complaints from a German business group must be asking themselves. At one point the article told readers:

“Major unions negotiated inflation-busting hikes in pay checks last year after years of wage restraint, although the Statistics Office said last month real wages across Germany were likely to have fallen in 2013.”

It’s not clear what the definition of “inflation-busting” is in this context, but it doesn’t sound like it involved large pay increases if wages did not even keep pace with inflation. Usually, they would be expected to rise somewhat in excess of inflation to reflect productivity growth in Germany’s economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The media were filled with euphoric accounts about the run-up in the stock market in 2013. This was certainly good news for the people who own lots of stock, less so for everyone else. (The generational warriors who yap about government debt hurting our kids would also be yelling about the stock market run-up transferring resources from young to old, if they were honest.)

Anyhow, it would be reasonable if this reporting included some discussion of the implications of higher stock prices for future returns. With the ratio of stock prices to trend corporate earnings now in the neighborhood of 20 to 1, the expected return for the future is around 5 percent annually in real terms. By contrast, the historic average for stocks in the United States is over 7 percent.

Unless future growth vastly exceeds anyone’s predictions, given its current value it is not possible for the market to sustain 7 percent real returns for any substantial period of time. This means that investors in stock must be willing to accept lower than historic rates of return.

The media were filled with euphoric accounts about the run-up in the stock market in 2013. This was certainly good news for the people who own lots of stock, less so for everyone else. (The generational warriors who yap about government debt hurting our kids would also be yelling about the stock market run-up transferring resources from young to old, if they were honest.)

Anyhow, it would be reasonable if this reporting included some discussion of the implications of higher stock prices for future returns. With the ratio of stock prices to trend corporate earnings now in the neighborhood of 20 to 1, the expected return for the future is around 5 percent annually in real terms. By contrast, the historic average for stocks in the United States is over 7 percent.

Unless future growth vastly exceeds anyone’s predictions, given its current value it is not possible for the market to sustain 7 percent real returns for any substantial period of time. This means that investors in stock must be willing to accept lower than historic rates of return.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers of a NYT article on Latvia entering the euro would assume. The piece presented it as good news that the euro had risen against the dollar over the last year. This increase will make the goods and services produced by euro zone countries less competitive in the world economy, reducing their exports and increasing their imports. With nearly all of the euro zone countries operating at levels of output well below potential GDP, it is difficult to see why they would view this loss of demand as a positive development.

The article also quoted a statement by Olli Rehn, vice president of the European Commission responsible for economic and monetary affairs, in which he referred to Latvia’s strong recovery. It would have been useful to note that even with the recent growth it has experienced Lativia’s economy is still almost 10 percent smaller than its pre-recession peak in 2007.

That’s what readers of a NYT article on Latvia entering the euro would assume. The piece presented it as good news that the euro had risen against the dollar over the last year. This increase will make the goods and services produced by euro zone countries less competitive in the world economy, reducing their exports and increasing their imports. With nearly all of the euro zone countries operating at levels of output well below potential GDP, it is difficult to see why they would view this loss of demand as a positive development.

The article also quoted a statement by Olli Rehn, vice president of the European Commission responsible for economic and monetary affairs, in which he referred to Latvia’s strong recovery. It would have been useful to note that even with the recent growth it has experienced Lativia’s economy is still almost 10 percent smaller than its pre-recession peak in 2007.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Do you remember back when we were worried that robots will take all of the jobs? There will be no work for any of us because we will have all been replaced by robots.

It turns out that we have even more to worry about. AP says that because of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancies, we face a huge demographic crunch. We will have hordes of retirees and no one to to do the work. Now that sounds really scary, at the same time we have no jobs because the robots took them we must also struggle with the fact that we have no one to do the work because everyone is old and retired.

Yes, these are the complete opposite arguments. It is possible for one or the other to be true, but only in Washington can both be problems simultaneously. In this case, I happen to be a good moderate and say that neither is true. There is no plausible story in which robots are going to make us all unemployed any time in the foreseeable future. Nor is there a case that the demographic will impoverish us.

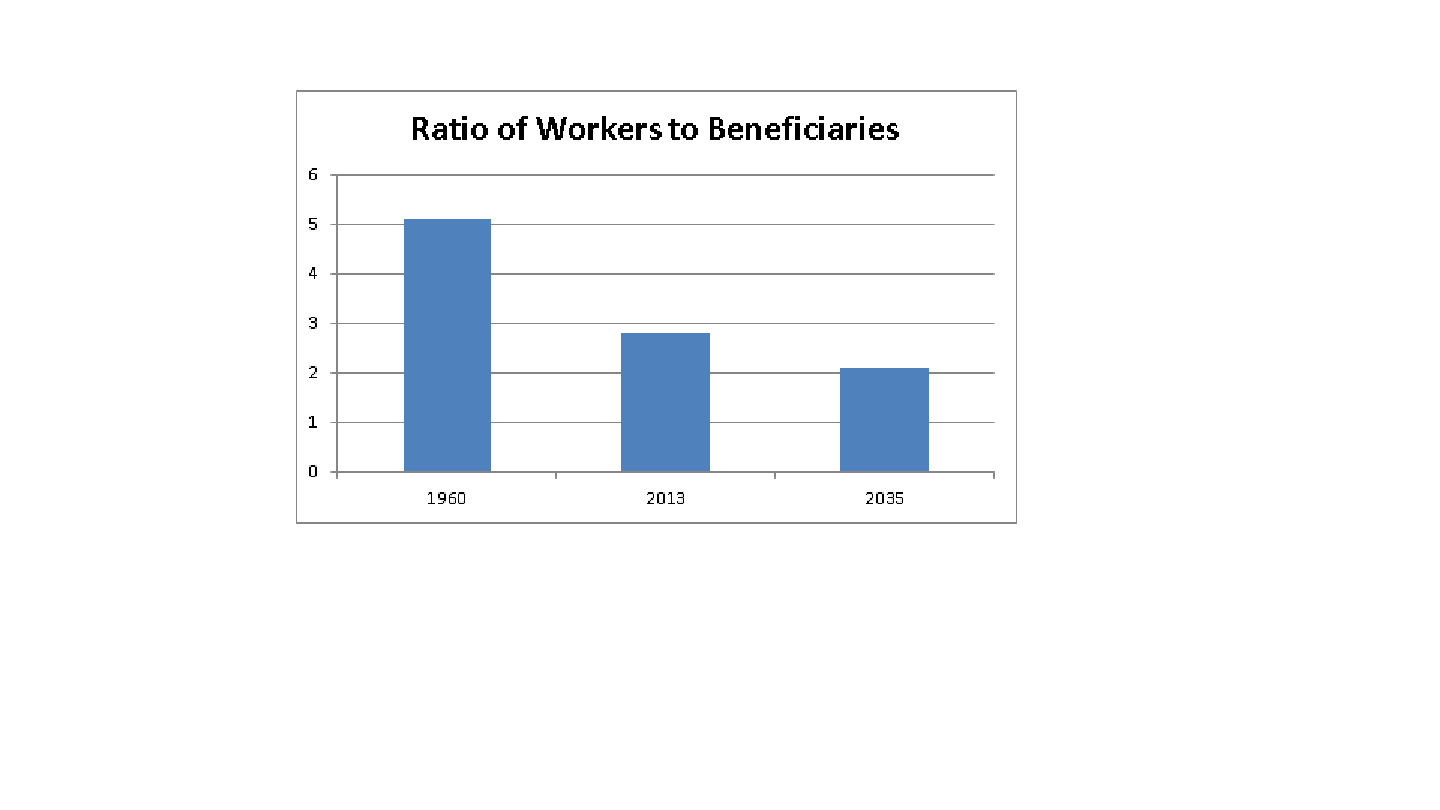

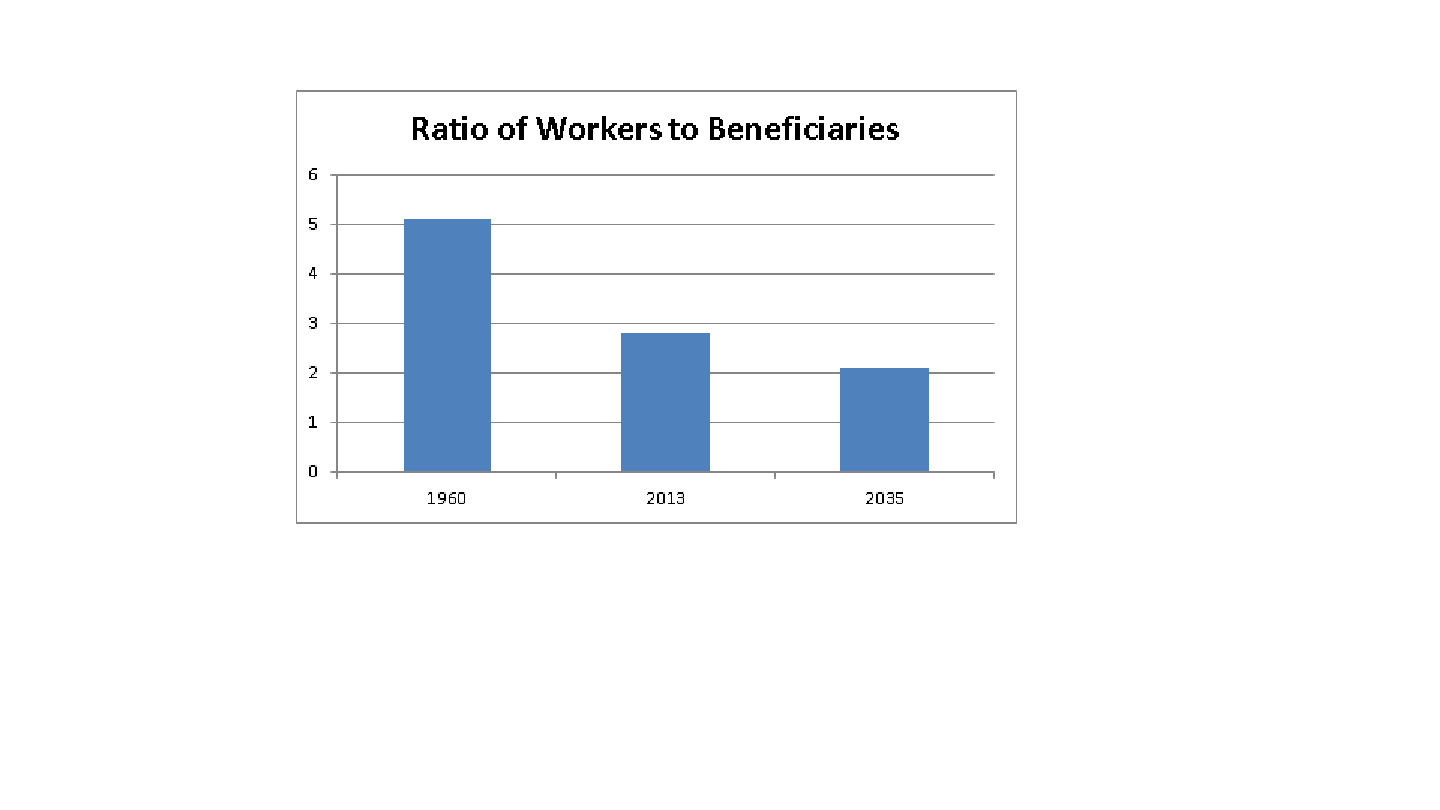

The basic story is that we have a rising ratio of retirees to workers, which should promote outraged cries of “so what?” Yes folks, we have had rising ratios of retirees to workers for a long time. In 1960 there was just one retiree for every five workers. Today there is one retiree for every 2.8 workers, and the Social Security trustees tell us that in 2035 there will be one retiree for every 2.1 workers.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

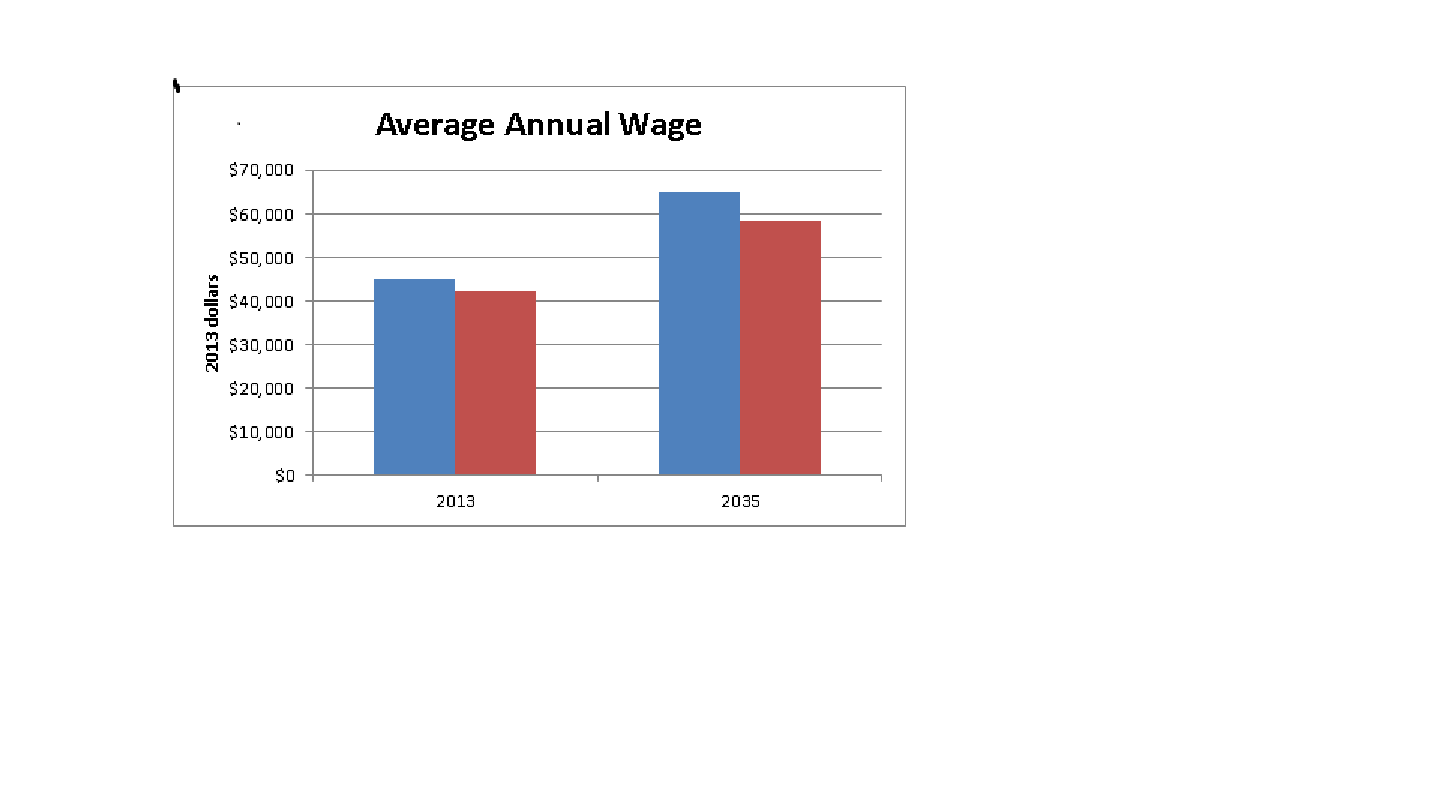

Just as the fall in the ratio of workers to retirees between 1960 and 2013 did not prevent both workers and retirees from enjoying substantially higher living standards, there is no reason to expect the further decline in the ratio to 2035 to lead to a fall in living standards.

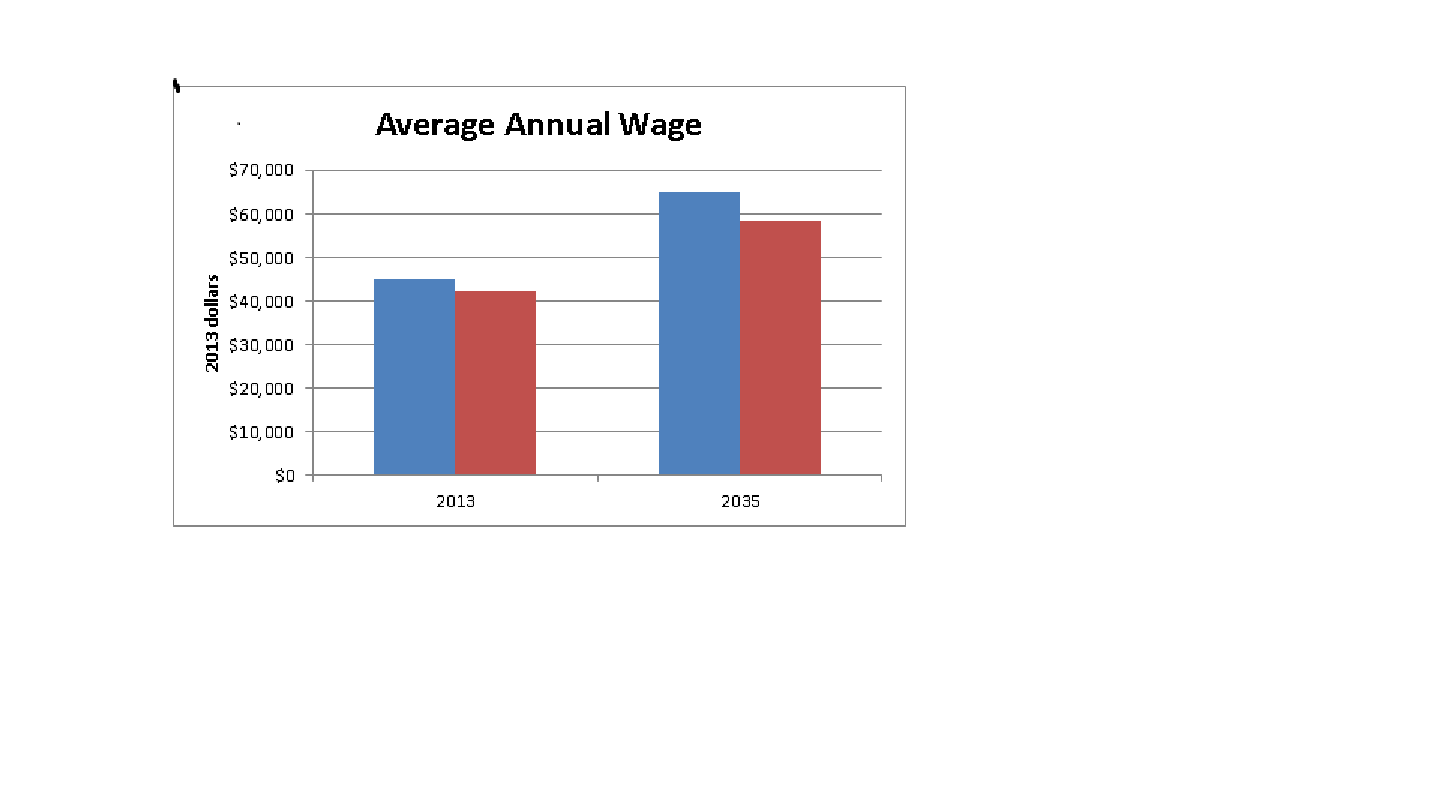

This point can be seen by comparing the average wage in 2013 with the average wage projected for 2035. The chart also includes the after-Social Security tax wage. The figure for 2035 assumes a 4.0 percentage point rise in the Social Security tax, an increase that is far larger than would be needed to keep the program fully funded under almost any conceivable circumstances. Even in this case, the average after tax wage would more than 38 percent higher than it is today.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

There is of course an issue of distribution. Most workers have not seen much benefit from the growth in average wages over the last three decades as most of the gains have gone to those at the top. But this points out yet again the urgency of addressing wage inequality. A continuing upward redistribution of income could make our children poor. Social Security and Medicare will not.

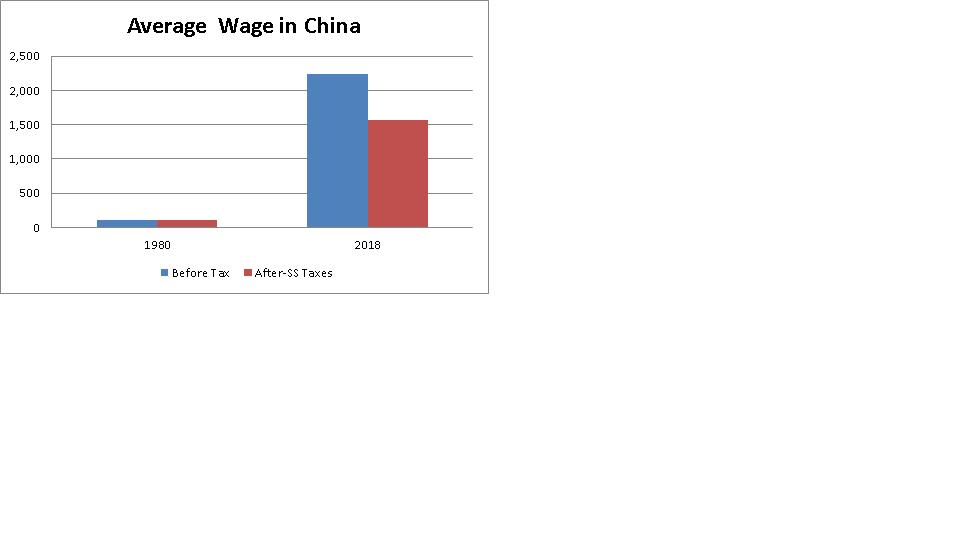

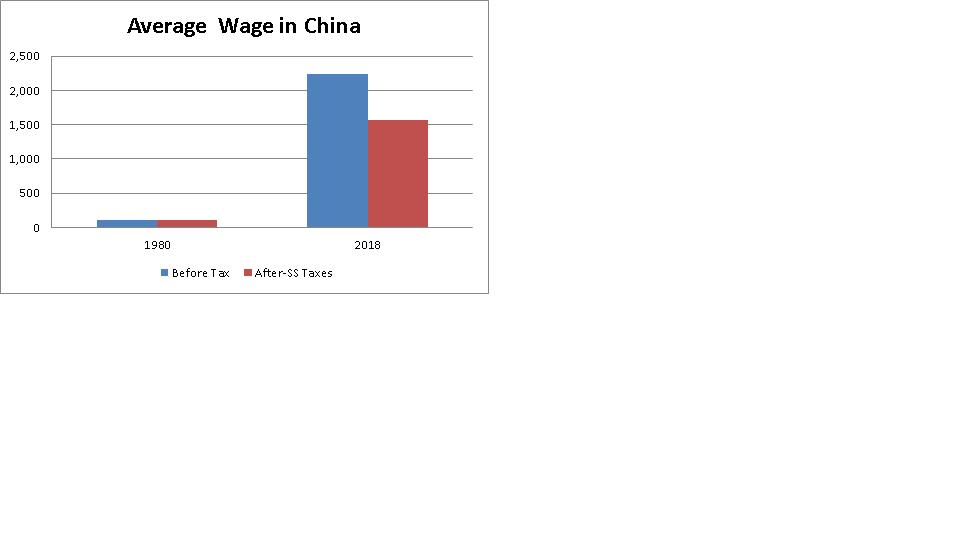

Finally, this AP article warns of the demographic nightmare facing China. Really?

China has seen incredible economic growth over the last three decades. As a result it is hugely richer today than it was in 1980. The chart below shows the ratio of real per capita income projected by the IMF for China in 2018 compared to its 1980 level. The projection for 2018 is more than 22 times as high as the 1980 level. The chart shows average wages under the assumption that wages grew in step with per capita income and a hypothetical after Social Security tax wage. The latter is calculated under the assumption that there was zero tax in 1980 and a 30 percent tax in 2018. (These are intended to be extreme assumptions.) Even in this case the average after-Social Security tax wage in 2018 would still be 15 times as high as the wage in 1980.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Of course in China, as with the United States, there has been an upward redistribution of income associated with a huge shift from wages to profits. As a result workers have not fully shared in the gains from growth over this period. But the limit in the gains to workers is clearly this distributional shift, not a deterioration in the country’s demographic picture.

In short, we have a seriously flawed scare story. The upward redistribution of income does pose a serious threat to the well-being of future generations of workers in the United States and elsewhere. The rise in the ratio of retirees to workers is not even an issue by comparison.

Do you remember back when we were worried that robots will take all of the jobs? There will be no work for any of us because we will have all been replaced by robots.

It turns out that we have even more to worry about. AP says that because of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancies, we face a huge demographic crunch. We will have hordes of retirees and no one to to do the work. Now that sounds really scary, at the same time we have no jobs because the robots took them we must also struggle with the fact that we have no one to do the work because everyone is old and retired.

Yes, these are the complete opposite arguments. It is possible for one or the other to be true, but only in Washington can both be problems simultaneously. In this case, I happen to be a good moderate and say that neither is true. There is no plausible story in which robots are going to make us all unemployed any time in the foreseeable future. Nor is there a case that the demographic will impoverish us.

The basic story is that we have a rising ratio of retirees to workers, which should promote outraged cries of “so what?” Yes folks, we have had rising ratios of retirees to workers for a long time. In 1960 there was just one retiree for every five workers. Today there is one retiree for every 2.8 workers, and the Social Security trustees tell us that in 2035 there will be one retiree for every 2.1 workers.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

Just as the fall in the ratio of workers to retirees between 1960 and 2013 did not prevent both workers and retirees from enjoying substantially higher living standards, there is no reason to expect the further decline in the ratio to 2035 to lead to a fall in living standards.

This point can be seen by comparing the average wage in 2013 with the average wage projected for 2035. The chart also includes the after-Social Security tax wage. The figure for 2035 assumes a 4.0 percentage point rise in the Social Security tax, an increase that is far larger than would be needed to keep the program fully funded under almost any conceivable circumstances. Even in this case, the average after tax wage would more than 38 percent higher than it is today.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

There is of course an issue of distribution. Most workers have not seen much benefit from the growth in average wages over the last three decades as most of the gains have gone to those at the top. But this points out yet again the urgency of addressing wage inequality. A continuing upward redistribution of income could make our children poor. Social Security and Medicare will not.

Finally, this AP article warns of the demographic nightmare facing China. Really?

China has seen incredible economic growth over the last three decades. As a result it is hugely richer today than it was in 1980. The chart below shows the ratio of real per capita income projected by the IMF for China in 2018 compared to its 1980 level. The projection for 2018 is more than 22 times as high as the 1980 level. The chart shows average wages under the assumption that wages grew in step with per capita income and a hypothetical after Social Security tax wage. The latter is calculated under the assumption that there was zero tax in 1980 and a 30 percent tax in 2018. (These are intended to be extreme assumptions.) Even in this case the average after-Social Security tax wage in 2018 would still be 15 times as high as the wage in 1980.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Of course in China, as with the United States, there has been an upward redistribution of income associated with a huge shift from wages to profits. As a result workers have not fully shared in the gains from growth over this period. But the limit in the gains to workers is clearly this distributional shift, not a deterioration in the country’s demographic picture.

In short, we have a seriously flawed scare story. The upward redistribution of income does pose a serious threat to the well-being of future generations of workers in the United States and elsewhere. The rise in the ratio of retirees to workers is not even an issue by comparison.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

To the amazement of millions David Brooks had an interesting observation in his column today. He picked up an article by my friend Steve Teles which outlines the story of kludgeocracy.

Steve’s idea is that we often end up advancing policy goals in incredible indirect and inefficient ways because this is the only way to move forward. The Affordable Care Act could be the poster child for this point. We got an incredibly complicated and unnecessarily expensive system because the insurers, the drug companies, the medical equipment suppliers, and the doctors all pushed to ensure that they would get their cut of the pie on the way to getting closer to universal coverage.

Steve gives many other examples in this article. My personal favorite is flexible spending accounts, which allow people to squirrel away some amount of money on a pre-tax basis to pay for health care expenses, child care expenses, or work-related transportation expenses. The point is to have the federal government subsidize these activities.

The absurdity is that the payroll costs to employers for administering these accounts are often a substantial portion of the money being saved. A fee of $20 per employee would not be unusual. If that employee puts aside $1000 a year in an account and is in the 25 percent tax bracket, this implies the tax subsidy is a bit less than $400. (The money is also exempted from the payroll tax.) A $20 fee would imply that 5 percent of the savings are being eaten up in administrative costs.

In addition, the worker loses money not spent by the end of the year. This gives them an incentive to buy items not really needed (e.g. an extra pair of glasses) to avoid losing the money. Filling out the forms can also be very time-consuming for workers.

The shape of the subsidy is also awful from a distributional standpoint. Wealthier people stand to get the largest subsidies.

Of course the government could just subsidize health care directly, which would be far more efficient. But, all the people in the financial industry who make profits from managing flexible spending accounts would be very upset. Therefore we can expect these accounts to be around for some time. This is kludgeocracy.

To the amazement of millions David Brooks had an interesting observation in his column today. He picked up an article by my friend Steve Teles which outlines the story of kludgeocracy.

Steve’s idea is that we often end up advancing policy goals in incredible indirect and inefficient ways because this is the only way to move forward. The Affordable Care Act could be the poster child for this point. We got an incredibly complicated and unnecessarily expensive system because the insurers, the drug companies, the medical equipment suppliers, and the doctors all pushed to ensure that they would get their cut of the pie on the way to getting closer to universal coverage.

Steve gives many other examples in this article. My personal favorite is flexible spending accounts, which allow people to squirrel away some amount of money on a pre-tax basis to pay for health care expenses, child care expenses, or work-related transportation expenses. The point is to have the federal government subsidize these activities.

The absurdity is that the payroll costs to employers for administering these accounts are often a substantial portion of the money being saved. A fee of $20 per employee would not be unusual. If that employee puts aside $1000 a year in an account and is in the 25 percent tax bracket, this implies the tax subsidy is a bit less than $400. (The money is also exempted from the payroll tax.) A $20 fee would imply that 5 percent of the savings are being eaten up in administrative costs.

In addition, the worker loses money not spent by the end of the year. This gives them an incentive to buy items not really needed (e.g. an extra pair of glasses) to avoid losing the money. Filling out the forms can also be very time-consuming for workers.

The shape of the subsidy is also awful from a distributional standpoint. Wealthier people stand to get the largest subsidies.

Of course the government could just subsidize health care directly, which would be far more efficient. But, all the people in the financial industry who make profits from managing flexible spending accounts would be very upset. Therefore we can expect these accounts to be around for some time. This is kludgeocracy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión