Roughly one third of all doctors are in the top one percent of the income distribution and the vast majority are in the top two percent. This likely explains both the reason as to why the government is not looking for ways to bring more doctors into the country and the reason the NYT is not raising the question in an article discussing a shortage of doctors willing to accept Medicaid reimbursement rates.

We have deliberately changed immigration rules and standards to make it easier for foreign computer engineers, nurses, and even teachers to enter the country and meet demand in these occupations. There is no economic reason why we would not do the same for doctors. The potential savings to consumers and the government and gains to economy would be several times larger for each qualified doctor that we brought into the country than for every nurse or teacher.

If the government were not actively engaged in efforts to redistribute income upward, regularizing a flow of doctors, with foreign students trained to U.S. standards, would be a major focus of trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. (We could design a mechanism to ensure that earnings of foreign doctors are taxed and repatriated to home countries so that developing countries could train 2-3 doctors for every one that comes to the United States. Even an economist could figure out how to design such a mechanism.)

Anyhow, it is remarkable how trade is so selectively defined that enormous potential gains that would disadvantage the wealthy never even get mentioned. While the protectionist barriers that cause doctors in the U.S. to get twice the pay as doctors in other wealthy countries never get mentioned, we get endless hysterics over a couple thousand dollars a year going to families receiving food stamps.

Try to swallow that one with your turkey.

Addendum:

The vast majority of the items on the agenda at NAFTA, CAFTA, the TPP and other recent trade agreements are not formal trade barriers. There are investment rules and various restrictions that made it difficult to for U.S. firms to establish operations in Mexico and other countries. These trade agreements focused on eliminating these barriers so that it would be easy. That is what we should be doing with doctors. (Here’s a partial list.) We don’t because the doctors are too powerful, and the promoters of free trade in the economics profession and the media don’t talk about it because ???

As far as the folks saying that I don’t care about people in the developing world, try answering my argument. Is it impossible to train more doctors in the developing world? If so, please tell us why. It is a hell of a lot cheaper to train doctors (to U.S. standards) anywhere other than the United States. If there is some reason why we should not take advantage of this fact, please let me and others know. If you just want to which righteously, maybe we can create a special section, for that.

Roughly one third of all doctors are in the top one percent of the income distribution and the vast majority are in the top two percent. This likely explains both the reason as to why the government is not looking for ways to bring more doctors into the country and the reason the NYT is not raising the question in an article discussing a shortage of doctors willing to accept Medicaid reimbursement rates.

We have deliberately changed immigration rules and standards to make it easier for foreign computer engineers, nurses, and even teachers to enter the country and meet demand in these occupations. There is no economic reason why we would not do the same for doctors. The potential savings to consumers and the government and gains to economy would be several times larger for each qualified doctor that we brought into the country than for every nurse or teacher.

If the government were not actively engaged in efforts to redistribute income upward, regularizing a flow of doctors, with foreign students trained to U.S. standards, would be a major focus of trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. (We could design a mechanism to ensure that earnings of foreign doctors are taxed and repatriated to home countries so that developing countries could train 2-3 doctors for every one that comes to the United States. Even an economist could figure out how to design such a mechanism.)

Anyhow, it is remarkable how trade is so selectively defined that enormous potential gains that would disadvantage the wealthy never even get mentioned. While the protectionist barriers that cause doctors in the U.S. to get twice the pay as doctors in other wealthy countries never get mentioned, we get endless hysterics over a couple thousand dollars a year going to families receiving food stamps.

Try to swallow that one with your turkey.

Addendum:

The vast majority of the items on the agenda at NAFTA, CAFTA, the TPP and other recent trade agreements are not formal trade barriers. There are investment rules and various restrictions that made it difficult to for U.S. firms to establish operations in Mexico and other countries. These trade agreements focused on eliminating these barriers so that it would be easy. That is what we should be doing with doctors. (Here’s a partial list.) We don’t because the doctors are too powerful, and the promoters of free trade in the economics profession and the media don’t talk about it because ???

As far as the folks saying that I don’t care about people in the developing world, try answering my argument. Is it impossible to train more doctors in the developing world? If so, please tell us why. It is a hell of a lot cheaper to train doctors (to U.S. standards) anywhere other than the United States. If there is some reason why we should not take advantage of this fact, please let me and others know. If you just want to which righteously, maybe we can create a special section, for that.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Stephen Roach managed to get the basic economics 180 degrees backwards in his discussion of China’s turn to a more consumption based economy and its implications for the United States. After commenting that China will likely export less to the United States as it produces more for its domestic economy, he tells readers;

“The coming transition to a rebalanced China changes the rules of engagement in this co-dependent relationship. America seems unprepared for this possibility. Long dependent on China as the world’s ultimate producer, the United States may have a hard time waking up to the reality of a China that is less focused on enabling America’s excess consumption and more interested in spending money on social services rather than buying Treasuries and helping to keep United States interest rates down.

“The United States needs to liberate itself from the mind-set that it cannot afford to change its economic strategy. It must shift the fixation on consumption for today’s generation to greater focus on saving and investing for future generations. The sluggish recovery and unacceptably high unemployment make this shift difficult, but not impossible.”

Contrary to what Roach asserts the sluggish recovery and high unemployment make the shift to fewer imports easier not harder. This means that we have excess workers and capacity that can be diverted to producing items that we used to import. If the opposite were the case and we were near full employment then the loss of imports from China would mean a decline in the standard of living. In the current situation, increased net exports (i.e. fewer imports) could mean more employment and output, in other words a rise in the U.S. standard of living.

Stephen Roach managed to get the basic economics 180 degrees backwards in his discussion of China’s turn to a more consumption based economy and its implications for the United States. After commenting that China will likely export less to the United States as it produces more for its domestic economy, he tells readers;

“The coming transition to a rebalanced China changes the rules of engagement in this co-dependent relationship. America seems unprepared for this possibility. Long dependent on China as the world’s ultimate producer, the United States may have a hard time waking up to the reality of a China that is less focused on enabling America’s excess consumption and more interested in spending money on social services rather than buying Treasuries and helping to keep United States interest rates down.

“The United States needs to liberate itself from the mind-set that it cannot afford to change its economic strategy. It must shift the fixation on consumption for today’s generation to greater focus on saving and investing for future generations. The sluggish recovery and unacceptably high unemployment make this shift difficult, but not impossible.”

Contrary to what Roach asserts the sluggish recovery and high unemployment make the shift to fewer imports easier not harder. This means that we have excess workers and capacity that can be diverted to producing items that we used to import. If the opposite were the case and we were near full employment then the loss of imports from China would mean a decline in the standard of living. In the current situation, increased net exports (i.e. fewer imports) could mean more employment and output, in other words a rise in the U.S. standard of living.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I can’t quite understand the persistence of the ageist nonsense about how the health care exchanges need young and healthy people to sign up for them to work. There is a real issue about adverse selection.

If the only people who sign up are unhealthy and therefore have high expenses, then insurers will have to raise their prices. This will make plans less attractive to all but the very sick, which will force further rises in prices, leading to a further narrowing of the market.

But the key issue is whether healthy people sign up in large numbers. It doesn’t matter where they are young or old, the exchanges need healthy people to effectively subsidize the care given to the less healthy.

In this respect a healthy 60-year-old is every bit as valuable as a healthy 25-year-old. In fact, the healthy 60-year-old is far more valuable to the system since their premiums will be three times as high as the premiums paid by the 25-year-old.

All of this should be pretty straightforward. The exchanges need healthy people to sign up to be viable, it doesn’t matter how old they are.

I can’t quite understand the persistence of the ageist nonsense about how the health care exchanges need young and healthy people to sign up for them to work. There is a real issue about adverse selection.

If the only people who sign up are unhealthy and therefore have high expenses, then insurers will have to raise their prices. This will make plans less attractive to all but the very sick, which will force further rises in prices, leading to a further narrowing of the market.

But the key issue is whether healthy people sign up in large numbers. It doesn’t matter where they are young or old, the exchanges need healthy people to effectively subsidize the care given to the less healthy.

In this respect a healthy 60-year-old is every bit as valuable as a healthy 25-year-old. In fact, the healthy 60-year-old is far more valuable to the system since their premiums will be three times as high as the premiums paid by the 25-year-old.

All of this should be pretty straightforward. The exchanges need healthy people to sign up to be viable, it doesn’t matter how old they are.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s why the NYT didn’t feel any need to put the number in context for its readers when it told readers of a deal between the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats to form a coalition government. According to the article the agreement calls for spending up to 2.0 billion euros a year on infrastructure above current spending levels.

Since many readers may not have a good idea of the size of Germany’s economy it might have been helpful to tell readers that this spending is equivalent to 0.07 percent of GDP. It would be comparable to the United States increasing spending roughly $11 billion more a year on infrastructure.

That’s why the NYT didn’t feel any need to put the number in context for its readers when it told readers of a deal between the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats to form a coalition government. According to the article the agreement calls for spending up to 2.0 billion euros a year on infrastructure above current spending levels.

Since many readers may not have a good idea of the size of Germany’s economy it might have been helpful to tell readers that this spending is equivalent to 0.07 percent of GDP. It would be comparable to the United States increasing spending roughly $11 billion more a year on infrastructure.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is effectively what the NYT told readers in an article discussing the reaction to a proposal by the IMF to require bondholders to accept losses when a government gets an IMF bailout. At one point the piece presented the comment of a Treasury Department spokesperson:

“It is important that efforts to increase the orderliness and predictability of the sovereign-debt restructuring process be undertaken on the basis of a consensual, market-based contractual framework.”

It then added:

“Translation: We don’t like plans that mess around with the rights of bond investors. We didn’t like them 10 years ago, and we don’t like them now.”

This is actually somewhat of a mistranslation. There is not an issue of “rights” here. The question is one of the rules that would apply when the IMF, a multinational institution, puts money into a bailout. In the absence of IMF money, it is extremely unlikely that bond investors would get back their full investment. The United States position is effectively that the IMF should intervene to ensure that bondholders get paid back even though they were not smart enough to assess credit risk when they bought the bonds. (Actually, many investors may buy bonds at sharp discounts when a country is in trouble, with the expectation that the IMF will intervene to ensure that the bonds are paid in full.)

There is no issue of rights here, since countries that go to the IMF for a bailout would generally not have the ability to pay their debt in any case. The NYT seriously misrepresented what is at stake to its readers.

The piece is also somewhat misleading in implying that Europe has a large amount of money at stake if the peripheral countries are allowed to partially default on their debt. Most of the debt is money from the European Central Bank (ECB). If the countries were to default, the ECB could simply print more with very little consequence for the real economy.

This is effectively what the NYT told readers in an article discussing the reaction to a proposal by the IMF to require bondholders to accept losses when a government gets an IMF bailout. At one point the piece presented the comment of a Treasury Department spokesperson:

“It is important that efforts to increase the orderliness and predictability of the sovereign-debt restructuring process be undertaken on the basis of a consensual, market-based contractual framework.”

It then added:

“Translation: We don’t like plans that mess around with the rights of bond investors. We didn’t like them 10 years ago, and we don’t like them now.”

This is actually somewhat of a mistranslation. There is not an issue of “rights” here. The question is one of the rules that would apply when the IMF, a multinational institution, puts money into a bailout. In the absence of IMF money, it is extremely unlikely that bond investors would get back their full investment. The United States position is effectively that the IMF should intervene to ensure that bondholders get paid back even though they were not smart enough to assess credit risk when they bought the bonds. (Actually, many investors may buy bonds at sharp discounts when a country is in trouble, with the expectation that the IMF will intervene to ensure that the bonds are paid in full.)

There is no issue of rights here, since countries that go to the IMF for a bailout would generally not have the ability to pay their debt in any case. The NYT seriously misrepresented what is at stake to its readers.

The piece is also somewhat misleading in implying that Europe has a large amount of money at stake if the peripheral countries are allowed to partially default on their debt. Most of the debt is money from the European Central Bank (ECB). If the countries were to default, the ECB could simply print more with very little consequence for the real economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

At its peak in 2006 the housing bubble in the United States created more than $8 trillion of bubble generated equity, making it the largest asset bubble in the history of the world. This one was easy to see to anyone who paid attention to fundamentals in the markets like long-term price trends, rents, and vacancy rates. The failure to see the bubble should raise questions about someone’s competence as an expert on the housing market.

For this reason it is distressing to see the Washington Post rely exclusively on people who missed the bubble in an article on the current state of the housing market. The piece implies that it is mixed news that house prices are not rising more rapidly, wrongly telling readers that:

“Rising values are essential for the approximately 7 million Americans whose mortgages are larger than their homes are worth.”

This is of course not true. Rising prices are desirable for any homeowner, but they certainly are not “essential” to underwater homeowners or anyone else. If an underwater homeowner can pay their mortgage and intends to stay in their home, then a period of being underwater does not carry great consequences. If they want to sell their home then it is certainly desirable that they have equity and aren’t in a situation where in principle they owe the bank money at the closing. But banks often will accept a short sale, which means that they treat the sale price as paying off the mortgage.

It would have been useful to point out to readers that house prices are already well above their long-term trend, suggesting that the market is at risk of being inflated by another bubble. This would mean that many new home buyers will pay bubble-inflated prices for their homes and face large losses in equity when prices return to trend levels. The return of a housing bubble can hardly be seen as a positive development.

The Post totally failed to note the existence of the last bubble, in part because it relied on David Lereah, the chief economist of the National Association of Realtors and the author of Why the Housing Boom Will Not Bust and How You can Profit from It, as its major source on the state of the housing market. It does not appear as though its reporting has improved in this area.

At its peak in 2006 the housing bubble in the United States created more than $8 trillion of bubble generated equity, making it the largest asset bubble in the history of the world. This one was easy to see to anyone who paid attention to fundamentals in the markets like long-term price trends, rents, and vacancy rates. The failure to see the bubble should raise questions about someone’s competence as an expert on the housing market.

For this reason it is distressing to see the Washington Post rely exclusively on people who missed the bubble in an article on the current state of the housing market. The piece implies that it is mixed news that house prices are not rising more rapidly, wrongly telling readers that:

“Rising values are essential for the approximately 7 million Americans whose mortgages are larger than their homes are worth.”

This is of course not true. Rising prices are desirable for any homeowner, but they certainly are not “essential” to underwater homeowners or anyone else. If an underwater homeowner can pay their mortgage and intends to stay in their home, then a period of being underwater does not carry great consequences. If they want to sell their home then it is certainly desirable that they have equity and aren’t in a situation where in principle they owe the bank money at the closing. But banks often will accept a short sale, which means that they treat the sale price as paying off the mortgage.

It would have been useful to point out to readers that house prices are already well above their long-term trend, suggesting that the market is at risk of being inflated by another bubble. This would mean that many new home buyers will pay bubble-inflated prices for their homes and face large losses in equity when prices return to trend levels. The return of a housing bubble can hardly be seen as a positive development.

The Post totally failed to note the existence of the last bubble, in part because it relied on David Lereah, the chief economist of the National Association of Realtors and the author of Why the Housing Boom Will Not Bust and How You can Profit from It, as its major source on the state of the housing market. It does not appear as though its reporting has improved in this area.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting piece discussing the bubble in social media type companies; however the article misses a couple of important issues. The bursting of the current bubble will not have the same consequences for the economy because it has not yet grown large enough to move the economy in the same way as the stock bubble of the 1990s or the housing bubble in the last decade. Both of those bubbles led to consumption booms through the wealth effect, in addition to a boom in whacky Internet start-up investment and housing construction. That story could change if the bubble keeps growing, but thus far it is not large enough to move the economy in a big way.

The other issue is that bubbles invariably involve an important component of redistribution as the bubble pushers get rich at the expense of others. In the 1990s, people like Steve Case, a founder of AOL, managed to get incredibly rich by selling out his stake at the peak of the bubble. The big losers were the shareholders of Time-Warner, who were kind enough to give away most of their company for nothing.

In the case of the housing bubble, sellers of homes in the bubble years came out way ahead at the expense of the people who bought into bubble inflated markets. And the Wall Street gang who made a fortune in financing the deals also were big winners.

It would be helpful to know who is losing in the current bubble. Are the buyers of Facebook, Twitter, and other high flyers pension funds and ordinary investors or hedge funds and rich people? In the former case, this bubble would imply some serious upward redistribution as the Mark Zuckerbergs of the world suck money away from the rest of us. In the latter case, it would simply be a question of redistribution among the one percent. Unfortunately this piece gives readers no insight on this topic.

The NYT had an interesting piece discussing the bubble in social media type companies; however the article misses a couple of important issues. The bursting of the current bubble will not have the same consequences for the economy because it has not yet grown large enough to move the economy in the same way as the stock bubble of the 1990s or the housing bubble in the last decade. Both of those bubbles led to consumption booms through the wealth effect, in addition to a boom in whacky Internet start-up investment and housing construction. That story could change if the bubble keeps growing, but thus far it is not large enough to move the economy in a big way.

The other issue is that bubbles invariably involve an important component of redistribution as the bubble pushers get rich at the expense of others. In the 1990s, people like Steve Case, a founder of AOL, managed to get incredibly rich by selling out his stake at the peak of the bubble. The big losers were the shareholders of Time-Warner, who were kind enough to give away most of their company for nothing.

In the case of the housing bubble, sellers of homes in the bubble years came out way ahead at the expense of the people who bought into bubble inflated markets. And the Wall Street gang who made a fortune in financing the deals also were big winners.

It would be helpful to know who is losing in the current bubble. Are the buyers of Facebook, Twitter, and other high flyers pension funds and ordinary investors or hedge funds and rich people? In the former case, this bubble would imply some serious upward redistribution as the Mark Zuckerbergs of the world suck money away from the rest of us. In the latter case, it would simply be a question of redistribution among the one percent. Unfortunately this piece gives readers no insight on this topic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That may be a bit of an overstatement, but the comments from Yi Gang, a deputy governor at China’s central bank, deserved much more attention than they received. According to Bloomberg, YI announced that the bank would no longer accumulate reserves since it does not believe it to be in China’s interest. The implication is that China’s currency will rise in value against the dollar and other major currencies.

This could have very important implications for the United States since it would likely mean a lower trade deficit. Since other developing countries have allowed their currencies to follow China’s, a higher valued yuan is likely to lead to a fall in the dollar against many developing country currencies. A reduction in the trade deficit would mean more growth and jobs. If the deficit would fall by 1 percentage point of GDP (@$165 billion) this would translate into roughly 1.4 million jobs directly and another 700,000 through respending effects for a total gain of 2.1 million jobs.

Since there is no politically plausible proposal that could have anywhere near as much impact on employment, this announcement from China’s central bank is likely the best job creation program that the United States is going to see. It deserves more attention than it has received.

That may be a bit of an overstatement, but the comments from Yi Gang, a deputy governor at China’s central bank, deserved much more attention than they received. According to Bloomberg, YI announced that the bank would no longer accumulate reserves since it does not believe it to be in China’s interest. The implication is that China’s currency will rise in value against the dollar and other major currencies.

This could have very important implications for the United States since it would likely mean a lower trade deficit. Since other developing countries have allowed their currencies to follow China’s, a higher valued yuan is likely to lead to a fall in the dollar against many developing country currencies. A reduction in the trade deficit would mean more growth and jobs. If the deficit would fall by 1 percentage point of GDP (@$165 billion) this would translate into roughly 1.4 million jobs directly and another 700,000 through respending effects for a total gain of 2.1 million jobs.

Since there is no politically plausible proposal that could have anywhere near as much impact on employment, this announcement from China’s central bank is likely the best job creation program that the United States is going to see. It deserves more attention than it has received.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

With the Fed promising to keep the overnight money rate at zero long into the future, while it throws $85 billion a month into the economy with its quantitative easing policy, many are no doubt wondering who is on watch against another outbreak of inflation.

Greg Mankiw gave us the answer to that question in his NYT column today. After noting that the job vacancy had risen to 2.8 percent, which Mankiw describes as “almost back to normal,” he tells readers;

“Data on wage inflation also suggest that the labor market has firmed up. Over the past year, average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees grew 2.2 percent, compared with 1.3 percent in the previous 12 months. Accelerating wage growth is not the sign of a deeply depressed labor market.”

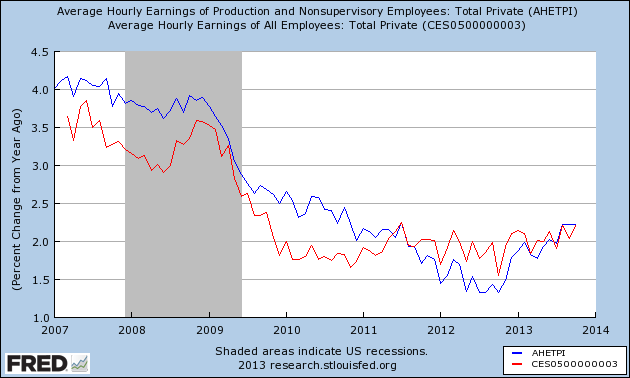

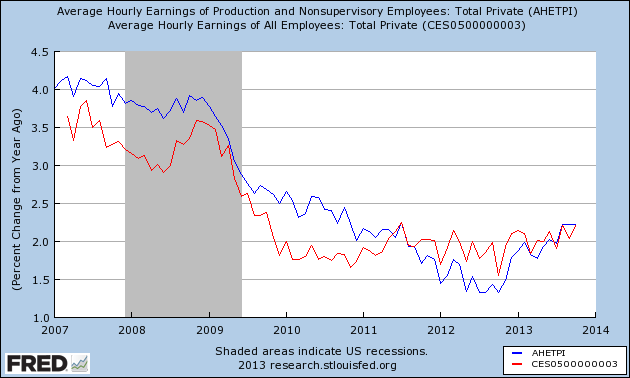

Let’s check this one out a bit more closely. The graph below shows the year over year growth in average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers (blue line) and all employees (red line). The former group comprises a bit more than 80 percent of the work force. The latter group tends to be more highly educated and is better paid on average.

If we look at the chart there is a modest acceleration in wage growth for production non-supervisory workers in 2013, but only because the rate of wage growth had continued to fall through 2012. If acceleration or deceleration is the measure of whether we have a fully utilized labor market we went quite quickly from a period of excess slack in 2012 when wages were falling to a period of tightness in the last year, even though employment growth has been rather tepid. That one seems a bit hard to accept.

Furthermore, if we use the broader measure of wage growth for all workers, we don’t see any evidence of acceleration at all. Wage growth has been hovering around 2.0 percent for the last two and a half years. It had been somewhat lower in 2010 (@ 1.6 percent), but there certainly is no upward pattern in this series.

A small upward tick in wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, but no change in overall wage growth, is evidence of a shift in relative demand not excess aggregate demand. It would suggest that the demand for workers with more education and skills is weakening relative to the demand for less educated workers. Of course the difference is relatively modest and could easily be reversed in the months ahead, but that is how economists would ordinarily read this evidence. (It is also important to remember that with inflation running just a bit under 2.0 percent, this translates into an annual rate real wage growth of only around half a percentage point.)

It is also worth noting that Mankiw’s other measure of a fully employed labor force is also dubious. At 2.8 percent the vacancy rate is up from its low in 2010, but this is a series that does not move much. There were two months in 2012 where the vacancy rate was 2.8 percent also. In the 2001 downturn, the rate never fell below 2.3 percent. (It had been as high as 3.8 percent before the recession.) In contrast to the rise in the vacancy rate back to near pre-recession levels, the number of people looking for work is more than 50 percent higher than before the recession. That is hardly consistent with a story with the labor market being near full employment.

With the Fed promising to keep the overnight money rate at zero long into the future, while it throws $85 billion a month into the economy with its quantitative easing policy, many are no doubt wondering who is on watch against another outbreak of inflation.

Greg Mankiw gave us the answer to that question in his NYT column today. After noting that the job vacancy had risen to 2.8 percent, which Mankiw describes as “almost back to normal,” he tells readers;

“Data on wage inflation also suggest that the labor market has firmed up. Over the past year, average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees grew 2.2 percent, compared with 1.3 percent in the previous 12 months. Accelerating wage growth is not the sign of a deeply depressed labor market.”

Let’s check this one out a bit more closely. The graph below shows the year over year growth in average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers (blue line) and all employees (red line). The former group comprises a bit more than 80 percent of the work force. The latter group tends to be more highly educated and is better paid on average.

If we look at the chart there is a modest acceleration in wage growth for production non-supervisory workers in 2013, but only because the rate of wage growth had continued to fall through 2012. If acceleration or deceleration is the measure of whether we have a fully utilized labor market we went quite quickly from a period of excess slack in 2012 when wages were falling to a period of tightness in the last year, even though employment growth has been rather tepid. That one seems a bit hard to accept.

Furthermore, if we use the broader measure of wage growth for all workers, we don’t see any evidence of acceleration at all. Wage growth has been hovering around 2.0 percent for the last two and a half years. It had been somewhat lower in 2010 (@ 1.6 percent), but there certainly is no upward pattern in this series.

A small upward tick in wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, but no change in overall wage growth, is evidence of a shift in relative demand not excess aggregate demand. It would suggest that the demand for workers with more education and skills is weakening relative to the demand for less educated workers. Of course the difference is relatively modest and could easily be reversed in the months ahead, but that is how economists would ordinarily read this evidence. (It is also important to remember that with inflation running just a bit under 2.0 percent, this translates into an annual rate real wage growth of only around half a percentage point.)

It is also worth noting that Mankiw’s other measure of a fully employed labor force is also dubious. At 2.8 percent the vacancy rate is up from its low in 2010, but this is a series that does not move much. There were two months in 2012 where the vacancy rate was 2.8 percent also. In the 2001 downturn, the rate never fell below 2.3 percent. (It had been as high as 3.8 percent before the recession.) In contrast to the rise in the vacancy rate back to near pre-recession levels, the number of people looking for work is more than 50 percent higher than before the recession. That is hardly consistent with a story with the labor market being near full employment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It might have been worth including this piece of information in a NYT piece on a new set of regulations that Wyoming is imposing on fracking. The piece notes that companies engaged in fracking are not required to disclose the mix of chemicals they use in the process in order to avoid giving away secrets to competitors.

This is precisely the reason that we have patents. If a company has an especially innovative mix of chemicals they would be able to get it patented and prevent their competitors from using it for 20 years. The fact that companies can obtain patent protection makes it implausible that protecting secrets is the real motive for their refusal to disclose the chemicals they are using.

It might have been worth including this piece of information in a NYT piece on a new set of regulations that Wyoming is imposing on fracking. The piece notes that companies engaged in fracking are not required to disclose the mix of chemicals they use in the process in order to avoid giving away secrets to competitors.

This is precisely the reason that we have patents. If a company has an especially innovative mix of chemicals they would be able to get it patented and prevent their competitors from using it for 20 years. The fact that companies can obtain patent protection makes it implausible that protecting secrets is the real motive for their refusal to disclose the chemicals they are using.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión