Eduardo Porter used his column today to point to a skills gap in the United States between the skills needed for the jobs being created and the skills of the people currently entering the workforce. The column rightly points out that this gap does not explain current unemployment and that employers could find more skilled workers if they offered higher wages. But it then refers to a study put out by the Brookings Institution:

“Mr. Rothwell says that the problem is getting bigger: while just under a third of the existing jobs in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas require a bachelor’s degree or more, about 43 percent of newly available jobs demand this degree. And only 32 percent of adults over the age of 25 have one.”

There are two points that should be made on this comment. First a small one: in the most recent data 33.5 percent of people age 25-29 had college degrees. And, the share of young people in large cities with college degrees would be even higher, since people with more education tend to gravitate to large cities. So the gap between the 43 percent figure and the share of the work force with degrees may not be that large. (It’s also worth noting that the Brooking study looked at vacancies in a severely depressed economy. These are going to be skewed towards higher end workers. When the economy is closer to full employment the ratio of retail clerks and assembly line workers to managers increases.)

The other more important point is the one raised earlier by Porter, employers are not raising wages for college grads. The wage is a signal. Higher wages tell young people that it is worthwhile to invest the time and money needed to get a college degree. If young people don’t anticipate a payoff for this investment, they won’t make it.

This is yet another enduring cost of the prolonged downturn. We can anticipate a future workforce that will be less well-educated because the downturn prevented the labor market from giving the right signals to young people.

Eduardo Porter used his column today to point to a skills gap in the United States between the skills needed for the jobs being created and the skills of the people currently entering the workforce. The column rightly points out that this gap does not explain current unemployment and that employers could find more skilled workers if they offered higher wages. But it then refers to a study put out by the Brookings Institution:

“Mr. Rothwell says that the problem is getting bigger: while just under a third of the existing jobs in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas require a bachelor’s degree or more, about 43 percent of newly available jobs demand this degree. And only 32 percent of adults over the age of 25 have one.”

There are two points that should be made on this comment. First a small one: in the most recent data 33.5 percent of people age 25-29 had college degrees. And, the share of young people in large cities with college degrees would be even higher, since people with more education tend to gravitate to large cities. So the gap between the 43 percent figure and the share of the work force with degrees may not be that large. (It’s also worth noting that the Brooking study looked at vacancies in a severely depressed economy. These are going to be skewed towards higher end workers. When the economy is closer to full employment the ratio of retail clerks and assembly line workers to managers increases.)

The other more important point is the one raised earlier by Porter, employers are not raising wages for college grads. The wage is a signal. Higher wages tell young people that it is worthwhile to invest the time and money needed to get a college degree. If young people don’t anticipate a payoff for this investment, they won’t make it.

This is yet another enduring cost of the prolonged downturn. We can anticipate a future workforce that will be less well-educated because the downturn prevented the labor market from giving the right signals to young people.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

According to the Washington Post, a debt default would have some clearly positive outcomes. Specifically it told readers that it would weaken the United States position as a financial safe haven for the rest of the world.

This would have two beneficial effects. If less money flowed from elsewhere in the world to the United States this would reduce the value of the dollar relative to other currencies. This has in fact been a stated goal of both the Bush and Obama administration, which both claimed that they wanted to end “currency manipulation.” Currency manipulation means that other countries are deliberately buying up dollars to raise the value of the dollar against their own currency.

The effort to end currency manipulation is an effort to lower the value of the dollar. If investors stop buying dollars because it is no longer a safe haven, then this would lower the value of the dollar in the same way that if foreign central banks stopped buying dollars to “manipulate” the value of their currency, it would lower the value of the dollar. In other words, people who would applaud the end of currency manipulation should also applaud the ending of the dollar as the world’s safe haven currency.

The other positive part of this story is that such a shift would lead to a downsizing of the financial industry in the United States. This would allow the resources in the sector to be reallocated to more productive sectors of the economy. It would also reduce the power of the financial industry in American politics.

A debt default may still be a bad story, but the vast majority of people in the United States have little to fear from the ending of the dollar as a safe haven currency.

According to the Washington Post, a debt default would have some clearly positive outcomes. Specifically it told readers that it would weaken the United States position as a financial safe haven for the rest of the world.

This would have two beneficial effects. If less money flowed from elsewhere in the world to the United States this would reduce the value of the dollar relative to other currencies. This has in fact been a stated goal of both the Bush and Obama administration, which both claimed that they wanted to end “currency manipulation.” Currency manipulation means that other countries are deliberately buying up dollars to raise the value of the dollar against their own currency.

The effort to end currency manipulation is an effort to lower the value of the dollar. If investors stop buying dollars because it is no longer a safe haven, then this would lower the value of the dollar in the same way that if foreign central banks stopped buying dollars to “manipulate” the value of their currency, it would lower the value of the dollar. In other words, people who would applaud the end of currency manipulation should also applaud the ending of the dollar as the world’s safe haven currency.

The other positive part of this story is that such a shift would lead to a downsizing of the financial industry in the United States. This would allow the resources in the sector to be reallocated to more productive sectors of the economy. It would also reduce the power of the financial industry in American politics.

A debt default may still be a bad story, but the vast majority of people in the United States have little to fear from the ending of the dollar as a safe haven currency.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I am not quite sure why, but apparently some people do take Niall Ferguson’s pronouncements on economics seriously. I usually ignore his comments, since I can’t imagine not having something better to do with my time. Nonetheless, I did note Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong beating up Ferguson for his failure to understand the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for the long-term budget deficit.

But rather than having the decency to find some rock behind which to hide, Harvard Professor Niall Ferguson rose to the occasion and tried to rewrite what he had earlier said. In a new blog post he writes:

“Which is more important then:

1. The fact that, as far as the CBO knows today, the fiscal position in 2038 will almost certainly be worse, and maybe much worse, than it is now?

OR

2. The fact that one of the CBO’s projections is not quite as bad this year as it was last year, when it was abominable, as opposed to just terrible.”

Well, there are all sorts or reasons why we should not be terribly worried about #1 (see my paper here for beginners), but for purposes at hand, #2 is exactly what Ferguson had argued in his original column where he highlighted the deterioration in the new CBO projections compared to the projections from 2012.

This one is not really debatable. Here’s the key paragraph:

“A very striking feature of the latest CBO report is how much worse it is than last year’s. A year ago, the CBO’s extended baseline series for the federal debt in public hands projected a figure of 52% of GDP by 2038. That figure has very nearly doubled to 100%. A year ago the debt was supposed to glide down to zero by the 2070s. This year’s long-run projection for 2076 is above 200%. In this devastating reassessment, a crucial role is played here by the more realistic growth assumptions used this year.”

I was always taught that when you make a mistake the best thing is to own up to it and apologize. Apparently at Harvard and the WSJ the accepted practice is to deny the error and to criticize the people who corrected it.

I am not quite sure why, but apparently some people do take Niall Ferguson’s pronouncements on economics seriously. I usually ignore his comments, since I can’t imagine not having something better to do with my time. Nonetheless, I did note Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong beating up Ferguson for his failure to understand the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for the long-term budget deficit.

But rather than having the decency to find some rock behind which to hide, Harvard Professor Niall Ferguson rose to the occasion and tried to rewrite what he had earlier said. In a new blog post he writes:

“Which is more important then:

1. The fact that, as far as the CBO knows today, the fiscal position in 2038 will almost certainly be worse, and maybe much worse, than it is now?

OR

2. The fact that one of the CBO’s projections is not quite as bad this year as it was last year, when it was abominable, as opposed to just terrible.”

Well, there are all sorts or reasons why we should not be terribly worried about #1 (see my paper here for beginners), but for purposes at hand, #2 is exactly what Ferguson had argued in his original column where he highlighted the deterioration in the new CBO projections compared to the projections from 2012.

This one is not really debatable. Here’s the key paragraph:

“A very striking feature of the latest CBO report is how much worse it is than last year’s. A year ago, the CBO’s extended baseline series for the federal debt in public hands projected a figure of 52% of GDP by 2038. That figure has very nearly doubled to 100%. A year ago the debt was supposed to glide down to zero by the 2070s. This year’s long-run projection for 2076 is above 200%. In this devastating reassessment, a crucial role is played here by the more realistic growth assumptions used this year.”

I was always taught that when you make a mistake the best thing is to own up to it and apologize. Apparently at Harvard and the WSJ the accepted practice is to deny the error and to criticize the people who corrected it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post told readers that a chart showing a spike in the interest rate on Treasury bills coming due on October 31 should scare us. The rate on short term notes has gone from near zero to around 0.29 percent. This is a huge hike in own percent, but it is still a pretty damn low interest rate.

The story here is pretty simple. These short term bills get much of their value from the fact that they are hugely liquid. Because of concerns over the debt ceiling they are no longer hugely liquid. Okay, this is not good news, but I just can’t get that scared over this. The financial markets will not freeze and the economy will not shut down because the interest rate on these notes is getting close to 0.3 percent.

Pushing the government against the debt ceiling is not smart and not going to be good for the economy (unless it ends the dollar’s status as the preeminent reserve currency), but we should refrain from telling horror stories.

The Washington Post told readers that a chart showing a spike in the interest rate on Treasury bills coming due on October 31 should scare us. The rate on short term notes has gone from near zero to around 0.29 percent. This is a huge hike in own percent, but it is still a pretty damn low interest rate.

The story here is pretty simple. These short term bills get much of their value from the fact that they are hugely liquid. Because of concerns over the debt ceiling they are no longer hugely liquid. Okay, this is not good news, but I just can’t get that scared over this. The financial markets will not freeze and the economy will not shut down because the interest rate on these notes is getting close to 0.3 percent.

Pushing the government against the debt ceiling is not smart and not going to be good for the economy (unless it ends the dollar’s status as the preeminent reserve currency), but we should refrain from telling horror stories.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It looks like CBS News can no longer afford to do their own news reporting so they are picking up material from other sources. There seems no other way to explain the piece it ran last night on the Social Security disability program on Sixty Minutes which is best described as a spinoff of an earlier This American Life piece.

The remarkable aspect of this story is that it completely ignored all the comments from experts in the field in response to the This American Life piece pointing out that fraud is in fact not rampant in the disability program (e.g. here and here). There were any number of experts who could have been interviewed on this topic to counterbalance the views of a far-right senator who is best known as a denier of global warming (Tom Coburn). But Sixty Minutes apparently could not be bothered to present a more balanced picture of the disability program.

The basic fact, which may be painful for CBS News and Sixty Minutes, is that it is not easy to get on Social Security disability. Close to three quarters of applicants are turned down initially and even after appeal, 60 percent of applicants are denied benefits.

If Sixty Minutes was actually interested in the incidence of fraudulent claims it might have turned to the authors of a University of Michigan study. This study identified a group of applicants who it considered marginal since they might be either approved or turned down, depending on the hearing officer who dealt with their case. Of this group (which comprised 23 percent of all applicants), 28 percent were working two years later if they were turned down. If we applied this to all disability approvals and assume that almost none of the non-marginal cases (i.e. more severely disabled cases) would be working, it means that less than 7.0 percent of the new applicants would be working two years later if the disability program did not exist.

Furthermore, the portion of this marginal group who were working after four years had fallen to just 16 percent. Their earnings averaged just 25-50 percent of their earnings in the years before they filed for disability. This hardly suggests widespread fraud.

Disability is a large program. That means there will be some fraud. This is not news, except perhaps at CBS.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of this story is that the Sixty Minutes crew seems to think they are being tough for going after people on disability. Needless to say they are far too cowardly to say anything about the failure in Washington to push either stimulus or a lowered valued dollar to boost net exports, a failure that is costing the country $1 trillion a year in lost output.

It looks like CBS News can no longer afford to do their own news reporting so they are picking up material from other sources. There seems no other way to explain the piece it ran last night on the Social Security disability program on Sixty Minutes which is best described as a spinoff of an earlier This American Life piece.

The remarkable aspect of this story is that it completely ignored all the comments from experts in the field in response to the This American Life piece pointing out that fraud is in fact not rampant in the disability program (e.g. here and here). There were any number of experts who could have been interviewed on this topic to counterbalance the views of a far-right senator who is best known as a denier of global warming (Tom Coburn). But Sixty Minutes apparently could not be bothered to present a more balanced picture of the disability program.

The basic fact, which may be painful for CBS News and Sixty Minutes, is that it is not easy to get on Social Security disability. Close to three quarters of applicants are turned down initially and even after appeal, 60 percent of applicants are denied benefits.

If Sixty Minutes was actually interested in the incidence of fraudulent claims it might have turned to the authors of a University of Michigan study. This study identified a group of applicants who it considered marginal since they might be either approved or turned down, depending on the hearing officer who dealt with their case. Of this group (which comprised 23 percent of all applicants), 28 percent were working two years later if they were turned down. If we applied this to all disability approvals and assume that almost none of the non-marginal cases (i.e. more severely disabled cases) would be working, it means that less than 7.0 percent of the new applicants would be working two years later if the disability program did not exist.

Furthermore, the portion of this marginal group who were working after four years had fallen to just 16 percent. Their earnings averaged just 25-50 percent of their earnings in the years before they filed for disability. This hardly suggests widespread fraud.

Disability is a large program. That means there will be some fraud. This is not news, except perhaps at CBS.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of this story is that the Sixty Minutes crew seems to think they are being tough for going after people on disability. Needless to say they are far too cowardly to say anything about the failure in Washington to push either stimulus or a lowered valued dollar to boost net exports, a failure that is costing the country $1 trillion a year in lost output.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the question that readers will inevitably ask after reading his column complaining that ideology is responsible for the government shutdown. Samuelson tells readers:

“A crucial difference between interest-group and ideological politics is what motivates people to join. For interest-group politics, the reason is simple — self-interest. People enjoy directly the fruits of their political involvement. Farmers get subsidies; Social Security recipients, checks. By contrast, the foot soldiers of ideological causes don’t usually enlist for tangible benefits for themselves but for a sense that they’re making the world a better place. Their reward is feeling good about themselves.

“I’ve called this “the politics of self-esteem” — and it profoundly alters politics. For starters, it suggests that you don’t just disagree with your adversaries; you also look down on them as morally inferior.”

Let’s see, does Robert Samuelson get direct tangible benefits when he harangues readers about the need to cut Social Security and Medicare because the country is projected to face a growing debt to GDP ratio in a decade or does this just make him feel good about himself?

That’s a tough one that we can leave folks to spend the day contemplating. But just to remind everyone of the facts of the situation, the projections, which incorporate little of the recent slowdown in health care costs (in other words, if the slowdown continues, we don’t have a problem) imply that the deficit will be somewhat larger in a decade than is consistent with a stable debt to GDP ratio.

If that projection proves accurate, there have been many times in the past in which the country has made far larger adjustments in its budget to deal with deficits (e.g. the Bush deficit reduction package in 1990 and the Clinton package in 1993), so it is hard to see why anyone would get so bent out of shape about the issue now. Since we are losing close to $1 trillion a year in lost output now and seeing millions of people have their lives ruined due to unemployment or underemployment, Samuelson’s deficit concerns seem a bit like obsessing over the need to repaint the kitchen when the house is on fire.

So, is he an ideologue?

That’s the question that readers will inevitably ask after reading his column complaining that ideology is responsible for the government shutdown. Samuelson tells readers:

“A crucial difference between interest-group and ideological politics is what motivates people to join. For interest-group politics, the reason is simple — self-interest. People enjoy directly the fruits of their political involvement. Farmers get subsidies; Social Security recipients, checks. By contrast, the foot soldiers of ideological causes don’t usually enlist for tangible benefits for themselves but for a sense that they’re making the world a better place. Their reward is feeling good about themselves.

“I’ve called this “the politics of self-esteem” — and it profoundly alters politics. For starters, it suggests that you don’t just disagree with your adversaries; you also look down on them as morally inferior.”

Let’s see, does Robert Samuelson get direct tangible benefits when he harangues readers about the need to cut Social Security and Medicare because the country is projected to face a growing debt to GDP ratio in a decade or does this just make him feel good about himself?

That’s a tough one that we can leave folks to spend the day contemplating. But just to remind everyone of the facts of the situation, the projections, which incorporate little of the recent slowdown in health care costs (in other words, if the slowdown continues, we don’t have a problem) imply that the deficit will be somewhat larger in a decade than is consistent with a stable debt to GDP ratio.

If that projection proves accurate, there have been many times in the past in which the country has made far larger adjustments in its budget to deal with deficits (e.g. the Bush deficit reduction package in 1990 and the Clinton package in 1993), so it is hard to see why anyone would get so bent out of shape about the issue now. Since we are losing close to $1 trillion a year in lost output now and seeing millions of people have their lives ruined due to unemployment or underemployment, Samuelson’s deficit concerns seem a bit like obsessing over the need to repaint the kitchen when the house is on fire.

So, is he an ideologue?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There are a couple of other points worth making on the Sixty Minutes piece beyond what I said earlier. First, the numbers involved should be put in some context. The Sixty Minutes folks were warning us that if the Disability fund runs dry, “it’s your money and our money.” So we should know how much of our money is at stake.

According to the Social Security Trustees Report, spending on the disability program in 2013 will be $144.8 billion. If we go to CEPR’s incredibly spiffy responsible budget reporting calculator we find that this sum is equal to 4.2 percent of spending for the year.

Before you run off and spend this windfall, it is important to remember that the bulk of the people collecting disability would almost certainly even fit Senator Coburn’s definition of disabled. We have people with terminal cancer, people who were paralyzed in car crashes, and many other ailments that undoubtedly impose a real impediment to work.

Based on what we know from the University of Michigan study, it is unlikely that even 10 percent of those collecting disability would fit most people’s definition of bogus claims. But just to humor our disability bashing friends at Sixty Minutes, let’s say that it’s 20 percent. That means that we can knock down federal spending by 0.84 percent ($29.0 billion) if we just crack the whip. That’s not trivial, but not enough to allow too many big fiestas with the savings.

This brings up the second point. The bogus cases will never be so polite as to identify themselves as bogus cases. In order to weed out a higher percentage of the people who should not be getting benefits we will have to tighten restrictions and deny a large share of claims. This will mean denying more claims that should be approved.

In other words, we can undoubtedly whittle down the number of bogus claims that get approved, but the cost will be that more legitimate claims will be turned down as well. So the price of denying benefits to some people who might be making too big of a deal out of back pain may be to deny benefits to people who can barely walk due to a back injury.

If the judgment of the hearing officers were perfect we wouldn’t have this problem, but it’s not. The question that anyone who wants to go the crackdown route has to answer is how many genuinely disabled people are you prepared to deny benefits in order to weed out a bogus applicant? Unfortunately, Sixty Minutes did not ask this question.

There are a couple of other points worth making on the Sixty Minutes piece beyond what I said earlier. First, the numbers involved should be put in some context. The Sixty Minutes folks were warning us that if the Disability fund runs dry, “it’s your money and our money.” So we should know how much of our money is at stake.

According to the Social Security Trustees Report, spending on the disability program in 2013 will be $144.8 billion. If we go to CEPR’s incredibly spiffy responsible budget reporting calculator we find that this sum is equal to 4.2 percent of spending for the year.

Before you run off and spend this windfall, it is important to remember that the bulk of the people collecting disability would almost certainly even fit Senator Coburn’s definition of disabled. We have people with terminal cancer, people who were paralyzed in car crashes, and many other ailments that undoubtedly impose a real impediment to work.

Based on what we know from the University of Michigan study, it is unlikely that even 10 percent of those collecting disability would fit most people’s definition of bogus claims. But just to humor our disability bashing friends at Sixty Minutes, let’s say that it’s 20 percent. That means that we can knock down federal spending by 0.84 percent ($29.0 billion) if we just crack the whip. That’s not trivial, but not enough to allow too many big fiestas with the savings.

This brings up the second point. The bogus cases will never be so polite as to identify themselves as bogus cases. In order to weed out a higher percentage of the people who should not be getting benefits we will have to tighten restrictions and deny a large share of claims. This will mean denying more claims that should be approved.

In other words, we can undoubtedly whittle down the number of bogus claims that get approved, but the cost will be that more legitimate claims will be turned down as well. So the price of denying benefits to some people who might be making too big of a deal out of back pain may be to deny benefits to people who can barely walk due to a back injury.

If the judgment of the hearing officers were perfect we wouldn’t have this problem, but it’s not. The question that anyone who wants to go the crackdown route has to answer is how many genuinely disabled people are you prepared to deny benefits in order to weed out a bogus applicant? Unfortunately, Sixty Minutes did not ask this question.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Catherine Rampell has a piece in the NYT Magazine about how the 1 percent made out like bandits in the wake of the collapse of the housing bubble (wrongly described as the financial crisis). Several of the claims or implications of the piece are not quite right. For example, the piece claims:

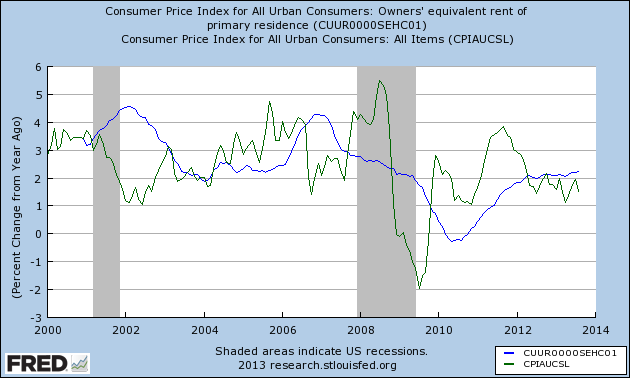

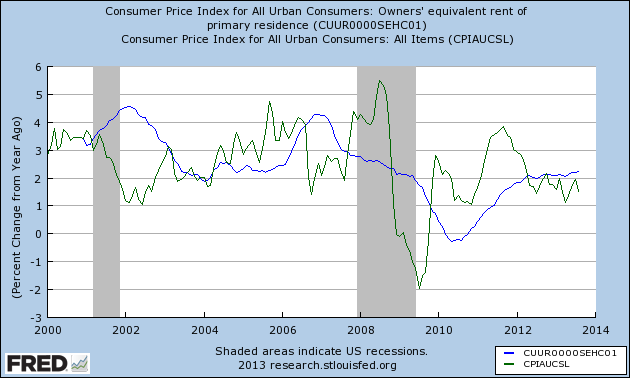

“Rents have risen at twice the pace of the overall cost-of-living index, partly because middle-class families can’t get the credit they need to buy.”

This is not true. There has been little difference in the rate of rental price increases and the overall increase in the cost of living since the start of the crisis as shown below. (The green line is overall inflation, the blue line owners equivalent rent. Owners’ equivalent rent is the appropriate comparison since it excludes utilities.)

This should not be surprising since the switch of people from homeowners to renters coinciding with conversion of many ownership units to rental properties, which is discussed in the piece. While the former increased the demand for rental units, the latter increased the supply.

A second misleading point is the idea that house prices have recovered to their bubble peaks. This is not in general true. In markets where there was not much of a bubble house prices have largely returned to their 2006 peaks in nominal terms, which would correspond to roughly a 15 percent decline in real terms. In areas where the bubble was centered, like Las Vegas and Phoenix, prices are still well below bubble peaks even in nominal terms.

Finally the piece cites work by David Autor about the loss of middle wage jobs. This was not actually happening in the years prior to the downturn. While it is likely true in the years since the downturn, this almost certainly a standard cyclical story. High unemployment always takes a toll on middle and lower wage workers. Since people in Washington can’t talk about anything that will get us back to full employment (e.g. stimulus, a lower valued dollar, or work sharing), we are likely to continue to see workers in the middle and below take a big hit. But this is a policy decision, not the result of natural economic trends as is explained in the forthcoming book by Jared Bernstein and me (Returning to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People, coming soon to a website near you.)

Catherine Rampell has a piece in the NYT Magazine about how the 1 percent made out like bandits in the wake of the collapse of the housing bubble (wrongly described as the financial crisis). Several of the claims or implications of the piece are not quite right. For example, the piece claims:

“Rents have risen at twice the pace of the overall cost-of-living index, partly because middle-class families can’t get the credit they need to buy.”

This is not true. There has been little difference in the rate of rental price increases and the overall increase in the cost of living since the start of the crisis as shown below. (The green line is overall inflation, the blue line owners equivalent rent. Owners’ equivalent rent is the appropriate comparison since it excludes utilities.)

This should not be surprising since the switch of people from homeowners to renters coinciding with conversion of many ownership units to rental properties, which is discussed in the piece. While the former increased the demand for rental units, the latter increased the supply.

A second misleading point is the idea that house prices have recovered to their bubble peaks. This is not in general true. In markets where there was not much of a bubble house prices have largely returned to their 2006 peaks in nominal terms, which would correspond to roughly a 15 percent decline in real terms. In areas where the bubble was centered, like Las Vegas and Phoenix, prices are still well below bubble peaks even in nominal terms.

Finally the piece cites work by David Autor about the loss of middle wage jobs. This was not actually happening in the years prior to the downturn. While it is likely true in the years since the downturn, this almost certainly a standard cyclical story. High unemployment always takes a toll on middle and lower wage workers. Since people in Washington can’t talk about anything that will get us back to full employment (e.g. stimulus, a lower valued dollar, or work sharing), we are likely to continue to see workers in the middle and below take a big hit. But this is a policy decision, not the result of natural economic trends as is explained in the forthcoming book by Jared Bernstein and me (Returning to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People, coming soon to a website near you.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what he told readers in an NYT column today. Paulson wrote:

“China’s economic output expanded nearly six-fold between 2002 and 2012, from $1.5 trillion to $8.3 trillion.”

It appears that Paulson took China’s GDP in nominal dollars. This distorts its actual growth both because more inflation in the United States would imply more rapid growth in China by this measure and also because much of the rise was simply an increase in the value of the yuan against the dollar.

The more standard measure would be inflation adjusted growth measured in China’s currency. This still comes to an extraordinary 10.7 percent annual rate, but that’s hugely different from the 18.7 percent rate implied by Paulson’s numbers.

This raises two disturbing questions. Is Paulson really that ignorant of both China’s economy and world growth data more generally? No one who has been through an intro econ class should ever mistake real and nominal growth like this. By Paulson’s measure, countries throughout the world experienced enormous growth in the 1970s because of inflation in the United States. This confusion is kind of scary for a person who both ran the country largest investment bank (Goldman Sachs) and was Treasury Secretary as the bursting of the housing bubble gave the country the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

The other question is whether the NYT suspends its fact-checking for prominent people like Henry Paulson. I have written columns for the NYT. I was asked to document every specific claim in my piece. That is appropriate and good journalistic practice for a newspaper that wants to ensure that the arguments it presents on its opinion page are based in reality. It is hard to believe that any fact-checker would have accepted Paulson’s claims about the size of China’s economy increasing six-fold from 2002-2012.

That’s what he told readers in an NYT column today. Paulson wrote:

“China’s economic output expanded nearly six-fold between 2002 and 2012, from $1.5 trillion to $8.3 trillion.”

It appears that Paulson took China’s GDP in nominal dollars. This distorts its actual growth both because more inflation in the United States would imply more rapid growth in China by this measure and also because much of the rise was simply an increase in the value of the yuan against the dollar.

The more standard measure would be inflation adjusted growth measured in China’s currency. This still comes to an extraordinary 10.7 percent annual rate, but that’s hugely different from the 18.7 percent rate implied by Paulson’s numbers.

This raises two disturbing questions. Is Paulson really that ignorant of both China’s economy and world growth data more generally? No one who has been through an intro econ class should ever mistake real and nominal growth like this. By Paulson’s measure, countries throughout the world experienced enormous growth in the 1970s because of inflation in the United States. This confusion is kind of scary for a person who both ran the country largest investment bank (Goldman Sachs) and was Treasury Secretary as the bursting of the housing bubble gave the country the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

The other question is whether the NYT suspends its fact-checking for prominent people like Henry Paulson. I have written columns for the NYT. I was asked to document every specific claim in my piece. That is appropriate and good journalistic practice for a newspaper that wants to ensure that the arguments it presents on its opinion page are based in reality. It is hard to believe that any fact-checker would have accepted Paulson’s claims about the size of China’s economy increasing six-fold from 2002-2012.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión