Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal reports that Olli Rehn, the European Union’s top economic official, is very upset over a new IMF report acknowledging mistakes in the bailout of Greece. Rehn apparently feels no mistakes were made. Hey 25 percent unemployment? What could be wrong?

The Wall Street Journal reports that Olli Rehn, the European Union’s top economic official, is very upset over a new IMF report acknowledging mistakes in the bailout of Greece. Rehn apparently feels no mistakes were made. Hey 25 percent unemployment? What could be wrong?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

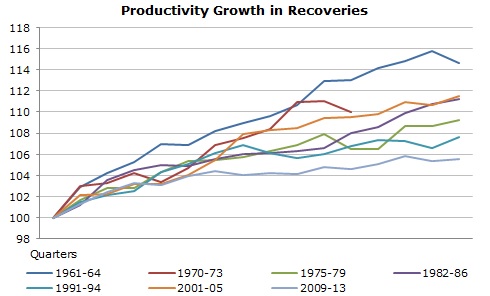

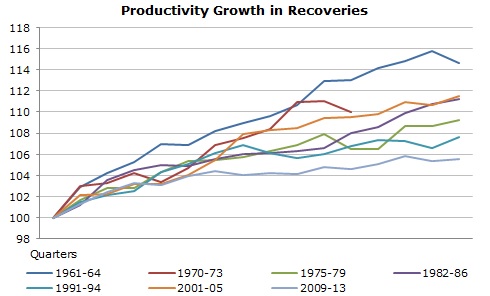

Some of us (well at least me) are surprised that an economy growing at a rate of 2.0 percent or less can create around 1.8 million jobs a year. That doesn’t seem to fit. We had been seeing productivity growth of close to 2.5 percent. At that rate the economy could grow 2.0 percent a year with no additional labor. So what is going on?

Well, we aren’t seeing productivity growth of 2.5 percent a year any more. In fact, in the last two years productivity growth has grown at less than a 1.0 percent annual rate. This is a sharp departure from the pattern in past upturns where we have seen strong productivity growth in the first years of the recovery.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This is the secret to job growth in this recovery. The question is whether the slowdown in productivity growth is permanent or just a response to a weak economy. The latter story would be that workers are taking low paying and low productivity jobs because there is nothing else available. This would be the more optimistic scenario since it would mean once we ever got a policy that actually generated demand we would return to a path of healthy productivity growth.

Remarkably, we have a whole group of policy types running around worried that we won’t have any jobs because robots will displace everyone. This is occurring at a time where the data is showing the exact opposite with the recent stretch of slow productivity growth. This would be amazing until we remember that these are the folks that took the Reinhart-Rogoff story seriously for the last three years.

Note:

The X-axis shows productivity in the first 15 quarters of the recovery (except for the 1970-73 upturn, which didn’t last that long). For reasons unknown to me, the tick marks disappeared in the transition from Excel. Obviously this is yet another Excel spreadsheet error.

Some of us (well at least me) are surprised that an economy growing at a rate of 2.0 percent or less can create around 1.8 million jobs a year. That doesn’t seem to fit. We had been seeing productivity growth of close to 2.5 percent. At that rate the economy could grow 2.0 percent a year with no additional labor. So what is going on?

Well, we aren’t seeing productivity growth of 2.5 percent a year any more. In fact, in the last two years productivity growth has grown at less than a 1.0 percent annual rate. This is a sharp departure from the pattern in past upturns where we have seen strong productivity growth in the first years of the recovery.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This is the secret to job growth in this recovery. The question is whether the slowdown in productivity growth is permanent or just a response to a weak economy. The latter story would be that workers are taking low paying and low productivity jobs because there is nothing else available. This would be the more optimistic scenario since it would mean once we ever got a policy that actually generated demand we would return to a path of healthy productivity growth.

Remarkably, we have a whole group of policy types running around worried that we won’t have any jobs because robots will displace everyone. This is occurring at a time where the data is showing the exact opposite with the recent stretch of slow productivity growth. This would be amazing until we remember that these are the folks that took the Reinhart-Rogoff story seriously for the last three years.

Note:

The X-axis shows productivity in the first 15 quarters of the recovery (except for the 1970-73 upturn, which didn’t last that long). For reasons unknown to me, the tick marks disappeared in the transition from Excel. Obviously this is yet another Excel spreadsheet error.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT gets the economics upside down in a piece discussing the protests in Turkey. At one point it tells readers:

“And like Spain and Greece before 2008, Turkey runs one of the largest current account deficits in the world, at around 7 percent of G.D.P. That, economists say, sets in motion a vicious circle as an overheated economy sucks in imports. That, in turn, creates a stronger currency that hurts the country’s exports, forcing Turkey to borrow ever more to finance the gap.”

Okay, so we have a large current account deficit that somehow leads to an overheated economy, that sucks in imports. That in turn creates a stronger currency.

Let’s get out the textbook. Turkey has a current account deficit primarily because the high value of its currency makes imports relatively cheap and its exports more expensive for people living in other countries. The causation is from high currency value to current account deficit.

The deficit means that Turkey is buying goods and services from other countries rather than spending it domestically. This reduces demand in Turkey, making the economy less overheated, not more.

Finally the current account deficit sends money out of the country, it increases the supply of Turkish currency on international markets. That should lower the value of Turkey’s currency, not raise it.

In this context, the recent fall in the Turkish lira that is highlighted in the article would be exactly what the doctor ordered. This would make Turkish goods more competitive internationally and reduce the size of the trade deficit.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Bill.

The NYT gets the economics upside down in a piece discussing the protests in Turkey. At one point it tells readers:

“And like Spain and Greece before 2008, Turkey runs one of the largest current account deficits in the world, at around 7 percent of G.D.P. That, economists say, sets in motion a vicious circle as an overheated economy sucks in imports. That, in turn, creates a stronger currency that hurts the country’s exports, forcing Turkey to borrow ever more to finance the gap.”

Okay, so we have a large current account deficit that somehow leads to an overheated economy, that sucks in imports. That in turn creates a stronger currency.

Let’s get out the textbook. Turkey has a current account deficit primarily because the high value of its currency makes imports relatively cheap and its exports more expensive for people living in other countries. The causation is from high currency value to current account deficit.

The deficit means that Turkey is buying goods and services from other countries rather than spending it domestically. This reduces demand in Turkey, making the economy less overheated, not more.

Finally the current account deficit sends money out of the country, it increases the supply of Turkish currency on international markets. That should lower the value of Turkey’s currency, not raise it.

In this context, the recent fall in the Turkish lira that is highlighted in the article would be exactly what the doctor ordered. This would make Turkish goods more competitive internationally and reduce the size of the trade deficit.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Bill.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Harold Meyerson has an interesting column warning of conditions that are likely to be in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. However it is misleading in one important respect.

At one point the article notes efforts by Senator Sherrod Brown to require rules that will the United States to retaliate against currency “manipulators,” countries that deliberately prop up the value of the dollar against their own currency in order to increase their trade surplus. This is misleading because the United States already has this authority (see this piece, for example) and under almost any conceivable set of circumstances will possess ample means to force down the value of the dollar relative to other currencies.

The reason that the United States runs an over-valued currency, placing U.S. goods and services at a competitive disadvantage, is that powerful interest groups profit from having an over-valued currency. Retailers like Walmart have spent large amounts of money setting up low-cost supply chains in China and other developing countries. This is an important source of their advantage over smaller competitors. They are not anxious to see this advantage eroded by a fall in the value of the dollar.

Similarly, large manufacturers like GE have much of their production overseas. These companies also do not want to see their profits eroded by a fall in the value of the dollar. Major financial companies like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan also tend to favor a high dollar since it means that their money goes further elsewhere in the world and it minimizes the risk of inflation in the United States.

These and other powerful domestic interests are the main reason that the United States does not take steps to reduce the value of the dollar and bring the trade deficit closer to balance. It is misleading to imply that the problem is trade agreements that prevent the Obama administration from acting.

Note — “rise” was changed to “fall” in 3rd paragraph, thanks David H.

Harold Meyerson has an interesting column warning of conditions that are likely to be in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. However it is misleading in one important respect.

At one point the article notes efforts by Senator Sherrod Brown to require rules that will the United States to retaliate against currency “manipulators,” countries that deliberately prop up the value of the dollar against their own currency in order to increase their trade surplus. This is misleading because the United States already has this authority (see this piece, for example) and under almost any conceivable set of circumstances will possess ample means to force down the value of the dollar relative to other currencies.

The reason that the United States runs an over-valued currency, placing U.S. goods and services at a competitive disadvantage, is that powerful interest groups profit from having an over-valued currency. Retailers like Walmart have spent large amounts of money setting up low-cost supply chains in China and other developing countries. This is an important source of their advantage over smaller competitors. They are not anxious to see this advantage eroded by a fall in the value of the dollar.

Similarly, large manufacturers like GE have much of their production overseas. These companies also do not want to see their profits eroded by a fall in the value of the dollar. Major financial companies like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan also tend to favor a high dollar since it means that their money goes further elsewhere in the world and it minimizes the risk of inflation in the United States.

These and other powerful domestic interests are the main reason that the United States does not take steps to reduce the value of the dollar and bring the trade deficit closer to balance. It is misleading to imply that the problem is trade agreements that prevent the Obama administration from acting.

Note — “rise” was changed to “fall” in 3rd paragraph, thanks David H.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Clive Crook told readers in a Bloomberg column that:

“It’s silly to ask whether high public debt causes lower growth or vice versa as though it must be one or the other. Almost certainly, both are true. This reinforces the case for fiscal consolidation as the recovery strengthens — not just to restore fiscal room for maneuver but also to support longer-term growth.”

Both parts of this statement are close to ridiculous. How do we know that higher debt everywhere and always leads to slower growth; because Clive Crook asserts it? What is the logic? In the prior paragraph Crook gave the traditional crowding out story, with high interest rates crowding out investment and other spending, but in the sort of severe slump that we are now seeing crowding out is not an issue. So how do we know that higher debt will slow growth?

Furthermore, Crook apparently has never heard of a balance sheet. If there is a curse of debt, then all countries (the United States in particular) have an enormous amount of assets (e.g. land, fishing rights, carbon emission permits) that can be sold to reduce debt. Since he claims that debt has a negative impact on growth it would be possible to avoid this negative impact through a sale of assets that would reduce the debt.

But the real absurdity is Crook’s blanket assertion that “it is silly to ask.” Let’s go a step further, it is unbelievably silly not just to ask, but to try to quantify. Suppose that debt does indeed have a negative impact on growth and for some bizarre reason we can never sell assets. In order for this to be relevant to policy we have to know how much.

The original Excel spreadsheet error cliff implied a growth penalty of more than 1.0 percentage point for having debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 90 percent. That would be a powerful argument against allowing our debt to rise above this level. But now that the Reinhart-Rogoff debt cliff has been destroyed by accurate arithmetic, we don’t know the size of the growth penalty from high debt, even assuming that it is not zero.

Suppose that the penalty is 0.01 percentage point. Would this be a strong argument against policies that might quickly employ millions of workers? Probably not in most people’s books, but hey, serious people like Clive Crook says it’s silly to even ask such questions.

Note: “Crook” is now correctly spelled.

Clive Crook told readers in a Bloomberg column that:

“It’s silly to ask whether high public debt causes lower growth or vice versa as though it must be one or the other. Almost certainly, both are true. This reinforces the case for fiscal consolidation as the recovery strengthens — not just to restore fiscal room for maneuver but also to support longer-term growth.”

Both parts of this statement are close to ridiculous. How do we know that higher debt everywhere and always leads to slower growth; because Clive Crook asserts it? What is the logic? In the prior paragraph Crook gave the traditional crowding out story, with high interest rates crowding out investment and other spending, but in the sort of severe slump that we are now seeing crowding out is not an issue. So how do we know that higher debt will slow growth?

Furthermore, Crook apparently has never heard of a balance sheet. If there is a curse of debt, then all countries (the United States in particular) have an enormous amount of assets (e.g. land, fishing rights, carbon emission permits) that can be sold to reduce debt. Since he claims that debt has a negative impact on growth it would be possible to avoid this negative impact through a sale of assets that would reduce the debt.

But the real absurdity is Crook’s blanket assertion that “it is silly to ask.” Let’s go a step further, it is unbelievably silly not just to ask, but to try to quantify. Suppose that debt does indeed have a negative impact on growth and for some bizarre reason we can never sell assets. In order for this to be relevant to policy we have to know how much.

The original Excel spreadsheet error cliff implied a growth penalty of more than 1.0 percentage point for having debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 90 percent. That would be a powerful argument against allowing our debt to rise above this level. But now that the Reinhart-Rogoff debt cliff has been destroyed by accurate arithmetic, we don’t know the size of the growth penalty from high debt, even assuming that it is not zero.

Suppose that the penalty is 0.01 percentage point. Would this be a strong argument against policies that might quickly employ millions of workers? Probably not in most people’s books, but hey, serious people like Clive Crook says it’s silly to even ask such questions.

Note: “Crook” is now correctly spelled.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Come on folks, know what you are reporting. A NYT headline telling readers, “U.S. manufacturing gauge falls to June 2009 level,” makes no sense. The index, the Institute for Supply Management index of manufacturing activity, shows changes in manufacturing, not levels. This means that the comparison to June 2009 is at best misleading.

The June measure came after many months of severe contraction that was gradually coming to an end. The April reading follows more than three years where the index was generally showing rising levels of output. This hardly puts the manufacturing sector in the same position as it was in June of 2009, as many readers might be led to believe.

Come on folks, know what you are reporting. A NYT headline telling readers, “U.S. manufacturing gauge falls to June 2009 level,” makes no sense. The index, the Institute for Supply Management index of manufacturing activity, shows changes in manufacturing, not levels. This means that the comparison to June 2009 is at best misleading.

The June measure came after many months of severe contraction that was gradually coming to an end. The April reading follows more than three years where the index was generally showing rising levels of output. This hardly puts the manufacturing sector in the same position as it was in June of 2009, as many readers might be led to believe.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Congress is debating whether to cut the Food Stamp program, the government’s main nutrition program for low-income families. The coverage of this debate is a great example of “fraternity reporting,” that is reporting that shows you are a member of reporters fraternity but has nothing to do with informing the audience.

We see this by the convention of referring to the $80 billion annual budget for the program (here for example). It is standard practice to refer to the dollar amount being spent on the program, pretending that this is actually providing information to readers.

As a practical matter, almost no one has a clear sense of how much much $80 billion a year is. They don’t have their heads in budget documents. (Yes, I know the Post has a well-educated readership, but it doesn’t matter.) It would mean pretty much the same thing to the vast majority of readers if the number was $8 billion or $800 billion. Often budget numbers appear without even telling the readers the number of years being covered.

If the standard practice was to write the numbers as a percent of total spending it would be providing actual information to a large percentage of its readers. In this case, current spending on Food Stamps is a bit over 2.2 percent of total spending. This figure is bloated by the downturn, since people qualify for benefits based on their income and many of the unemployed or underemployed qualify. (Contrary to Republican claims, President Obama did not ease the eligibility rules for food stamps.) The projections show that spending on food stamps will fall to 1.2 percent of the budget over the next decade as unemployment falls back to more normal levels.

It would be useful if we had a debate based on an informed public, with the country actually having a sense of how much food stamps and other programs cost. However, as long as fraternity reporting is the norm, large segments of the public will continue to believe that half of the budget is going to pay for food stamps.

Congress is debating whether to cut the Food Stamp program, the government’s main nutrition program for low-income families. The coverage of this debate is a great example of “fraternity reporting,” that is reporting that shows you are a member of reporters fraternity but has nothing to do with informing the audience.

We see this by the convention of referring to the $80 billion annual budget for the program (here for example). It is standard practice to refer to the dollar amount being spent on the program, pretending that this is actually providing information to readers.

As a practical matter, almost no one has a clear sense of how much much $80 billion a year is. They don’t have their heads in budget documents. (Yes, I know the Post has a well-educated readership, but it doesn’t matter.) It would mean pretty much the same thing to the vast majority of readers if the number was $8 billion or $800 billion. Often budget numbers appear without even telling the readers the number of years being covered.

If the standard practice was to write the numbers as a percent of total spending it would be providing actual information to a large percentage of its readers. In this case, current spending on Food Stamps is a bit over 2.2 percent of total spending. This figure is bloated by the downturn, since people qualify for benefits based on their income and many of the unemployed or underemployed qualify. (Contrary to Republican claims, President Obama did not ease the eligibility rules for food stamps.) The projections show that spending on food stamps will fall to 1.2 percent of the budget over the next decade as unemployment falls back to more normal levels.

It would be useful if we had a debate based on an informed public, with the country actually having a sense of how much food stamps and other programs cost. However, as long as fraternity reporting is the norm, large segments of the public will continue to believe that half of the budget is going to pay for food stamps.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión