Economists generally like to see supply and demand determine prices. When there is a shortage of an item then the price is supposed to rise. At higher prices the supply increases and the demand falls, this eliminates the shortage.

For some reason this simple logic was altogether absent from a Washington Post article that was headlined “Germany struggles with skilled labor shortage, shrinking population.” Remarkably the piece never once mentions increasing wages. Instead it talks about efforts to bring in foreign workers.

It seems like Germany might be suffering from the same problem that is often the subject of news stories in the United States: managers who don’t know how to raise wages. The media have frequently reported on businesses who complain that they cannot find qualified workers.

Since there are very few occupations where real wages have been rising in the last five years, it seems that few people who run businesses understand how labor markets work. This suggests that there could be large gains to the economy if the government (both here and in Germany) offered remedial economic courses to business managers explaining the basics of labor markets. Then they would understand that if they want more workers they should offer higher wages. This would eliminate labor shortages and then we would no longer have to read silly pieces like this one in the Post.

Economists generally like to see supply and demand determine prices. When there is a shortage of an item then the price is supposed to rise. At higher prices the supply increases and the demand falls, this eliminates the shortage.

For some reason this simple logic was altogether absent from a Washington Post article that was headlined “Germany struggles with skilled labor shortage, shrinking population.” Remarkably the piece never once mentions increasing wages. Instead it talks about efforts to bring in foreign workers.

It seems like Germany might be suffering from the same problem that is often the subject of news stories in the United States: managers who don’t know how to raise wages. The media have frequently reported on businesses who complain that they cannot find qualified workers.

Since there are very few occupations where real wages have been rising in the last five years, it seems that few people who run businesses understand how labor markets work. This suggests that there could be large gains to the economy if the government (both here and in Germany) offered remedial economic courses to business managers explaining the basics of labor markets. Then they would understand that if they want more workers they should offer higher wages. This would eliminate labor shortages and then we would no longer have to read silly pieces like this one in the Post.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A couple of weeks ago the NYT had a piece offering a dire prognosis about the prospects for the Danish welfare state. I pointed out that this assessment did not fit the data, with Denmark doing considerably better than the United States on most standard economic measures. Nancy Folbre also wrote about Denmark’s welfare state in her Economix piece in the NYT last week. Today, the paper has a useful “Room for Debate” segment on the Danish welfare state. It would be great if this sort of exchange came about after every misleading article.

A couple of weeks ago the NYT had a piece offering a dire prognosis about the prospects for the Danish welfare state. I pointed out that this assessment did not fit the data, with Denmark doing considerably better than the United States on most standard economic measures. Nancy Folbre also wrote about Denmark’s welfare state in her Economix piece in the NYT last week. Today, the paper has a useful “Room for Debate” segment on the Danish welfare state. It would be great if this sort of exchange came about after every misleading article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

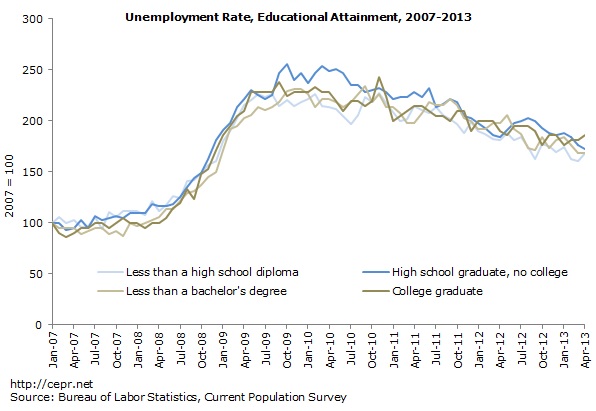

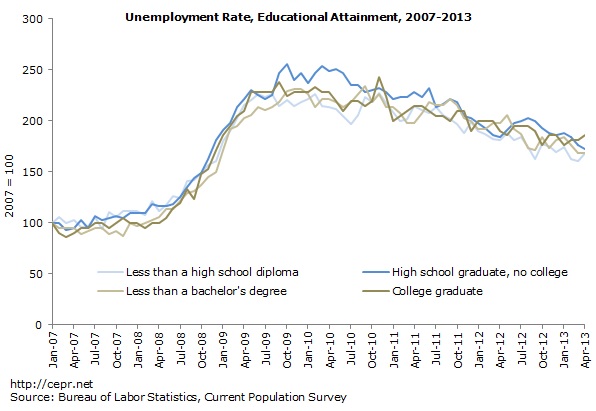

A NYT piece headlined, “college grads fare well in job market even through recession,” painted a misleading picture of the job market facing college grads in the downturn. First, the claim at the center of the piece, that college grads have gotten the bulk of the jobs in this recovery, is badly distorted by the pattern of retirements. The aging baby boomers who are leaving the labor force are much less likely to be college grads than the young people just entering, so even if there were no change in labor market conditions we would expect to see the share of college educated people increase among the employed. This effect is increased further as a result of the fact that less educated workers are likely to leave the work force at an earlier age because more of them work at physically demanding jobs.

In terms of relative changes in unemployment rates, college grads have fared no better than anyone else. In fact, they have done slightly worse than the least educated workers, those without high school degrees.

Finally, the claim about the returns to a college degree are misleading, especially for men. While on average men with college degrees get far higher incomes than those with just a high school degree, there is a wide degree of dispersion as shown by my colleague John Schmitt and Heather Boushey.. As a result, a large percentage of college grads earn lower wages than many high school grads. For this reason, the marginal student who is considering attending college may have good reason to question whether it will pay off for him. It would have been useful if this piece had spent more time discussing the specifics of this issue.

A NYT piece headlined, “college grads fare well in job market even through recession,” painted a misleading picture of the job market facing college grads in the downturn. First, the claim at the center of the piece, that college grads have gotten the bulk of the jobs in this recovery, is badly distorted by the pattern of retirements. The aging baby boomers who are leaving the labor force are much less likely to be college grads than the young people just entering, so even if there were no change in labor market conditions we would expect to see the share of college educated people increase among the employed. This effect is increased further as a result of the fact that less educated workers are likely to leave the work force at an earlier age because more of them work at physically demanding jobs.

In terms of relative changes in unemployment rates, college grads have fared no better than anyone else. In fact, they have done slightly worse than the least educated workers, those without high school degrees.

Finally, the claim about the returns to a college degree are misleading, especially for men. While on average men with college degrees get far higher incomes than those with just a high school degree, there is a wide degree of dispersion as shown by my colleague John Schmitt and Heather Boushey.. As a result, a large percentage of college grads earn lower wages than many high school grads. For this reason, the marginal student who is considering attending college may have good reason to question whether it will pay off for him. It would have been useful if this piece had spent more time discussing the specifics of this issue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson actually has a useful column today pointing out the imbalances that underlie the problems in the euro zone. The basic point is that the bubbles of the last decade led to a situation where prices in the crisis countries are hugely out of line with prices in the core countries, most importantly Germany. This means either substantial deflation in the crisis countries, considerably more rapid inflation in Germany and other core countries, or someone leaves the euro.

Samuelson rightly notes that none of these solutions seem likely right now for either economic or political reasons, or both. This means that the crisis is likely to persist for some time into the future.

However there is another part of the story that really deserves mentioning. What on earth were the folks at the European Central Bank (ECB) thinking in the years leading up to the crisis? The misalignment of prices in these countries did not arise overnight. There was considerably more rapid inflation in the current group of crisis countries in the last decade leading to enormous trade imbalances. Here’s the data from the IMF showing the deficits as a share of GDP.

Current Account Balance as a Percent of GDP

| Country | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | -6.533 | -5.785 | -7.637 | -11.388 | -14.609 | -14.922 |

| Portugal | -6.433 | -8.327 | -10.323 | -10.685 | -10.102 | -12.638 |

| Spain | -3.508 | -5.248 | -7.353 | -8.961 | -9.995 | -9.623 |

Source: International Monetary Fund.

These are incredible imbalances. In 2005, when the top people at the ECB went to the annual Fed meeting at Jackson Hole to celebrate the “Great Moderation” and debate whether Alan Greenspan was the greatest central banker of all time, the current account deficits in both Spain and Greece were already more than 7 percent of GDP. This would be a deficit of more than $1.1 trillion in the current U.S. economy. The deficit of 10.3 percent of GDP in Portugal would be almost $1.7 trillion in today’s economy. These deficits continued to expand, with Greece’s peaking at almost 15 percent of GDP ($2.4 trillion in the U.S. economy) in 2008.

How did the ECB think these imbalances made sense? There was some room for these countries to catch up relative to the core countries, but none of them was a China or India that could plausibly envision double-digit or near double-digit growth for decades. It’s hard to envision what story these people could have told themselves that did not have “disaster” in it. But, they did nothing and these economies collapsed.

The people in the crisis countries are now suffering enormously with no end in sight; and the boys and girls at the ECB? They still have their high paying jobs and plush pensions. See, the modern economy does offer good-paying jobs for people without skills.

Robert Samuelson actually has a useful column today pointing out the imbalances that underlie the problems in the euro zone. The basic point is that the bubbles of the last decade led to a situation where prices in the crisis countries are hugely out of line with prices in the core countries, most importantly Germany. This means either substantial deflation in the crisis countries, considerably more rapid inflation in Germany and other core countries, or someone leaves the euro.

Samuelson rightly notes that none of these solutions seem likely right now for either economic or political reasons, or both. This means that the crisis is likely to persist for some time into the future.

However there is another part of the story that really deserves mentioning. What on earth were the folks at the European Central Bank (ECB) thinking in the years leading up to the crisis? The misalignment of prices in these countries did not arise overnight. There was considerably more rapid inflation in the current group of crisis countries in the last decade leading to enormous trade imbalances. Here’s the data from the IMF showing the deficits as a share of GDP.

Current Account Balance as a Percent of GDP

| Country | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | -6.533 | -5.785 | -7.637 | -11.388 | -14.609 | -14.922 |

| Portugal | -6.433 | -8.327 | -10.323 | -10.685 | -10.102 | -12.638 |

| Spain | -3.508 | -5.248 | -7.353 | -8.961 | -9.995 | -9.623 |

Source: International Monetary Fund.

These are incredible imbalances. In 2005, when the top people at the ECB went to the annual Fed meeting at Jackson Hole to celebrate the “Great Moderation” and debate whether Alan Greenspan was the greatest central banker of all time, the current account deficits in both Spain and Greece were already more than 7 percent of GDP. This would be a deficit of more than $1.1 trillion in the current U.S. economy. The deficit of 10.3 percent of GDP in Portugal would be almost $1.7 trillion in today’s economy. These deficits continued to expand, with Greece’s peaking at almost 15 percent of GDP ($2.4 trillion in the U.S. economy) in 2008.

How did the ECB think these imbalances made sense? There was some room for these countries to catch up relative to the core countries, but none of them was a China or India that could plausibly envision double-digit or near double-digit growth for decades. It’s hard to envision what story these people could have told themselves that did not have “disaster” in it. But, they did nothing and these economies collapsed.

The people in the crisis countries are now suffering enormously with no end in sight; and the boys and girls at the ECB? They still have their high paying jobs and plush pensions. See, the modern economy does offer good-paying jobs for people without skills.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers of a Post article discussing the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would conclude. The piece includes assertions from two experts, David Stevens, president of the Mortgage Bankers Association, and Julia Gordon, the director of housing finance and policy at the Center for American Progress, that 30-year fixed rate mortgages would disappear if the government did not guarantee these mortgages through the GSEs or some other mechanism.

This can easily be shown not to be true by the market in jumbo mortgages. These are mortgages that are too large in value to be insured by the GSEs. A large share of these mortgages are 30-year fixed rate mortgages. Also, while it is less common today, prior to the housing bubble banks did hold a substantial share of their mortgages, typically around 10-20 percent. Since the government was not guaranteeing these mortgages, the banks must have felt the guarantee was unnecessary to get them to issue 30-year fixed rate mortgages.

The issue with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is one of the interest rates that people will pay on mortgages, not whether they will exist or not. By having a government guarantee the government is providing a subsidy to homebuyers that comes at the expense of the rest of the economy. The government already provides a subsidy to homebuyers through the mortgage interest deduction, the question is whether it is desirable to provide a further subsidy through this government guarantee.

There is also a question of whether this is the most efficient way to provide the subsidy. The government guarantee can set up a complex system of financial intermediaries that may be difficult to regulate. It may be more efficient to provide any additional subsidy to homeownership through an enhanced tax deduction or credit that would not lead to a bloated financial sector.

These are the issues that should be at the center of the debate over the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Post should have been able to recognize the absurdity of claims about the end of 30-year fixed rate mortgages and have found an expert to clarify this point.

Note: Corrected acronym to “GSE.” Thanks to David Stevens.

That’s what readers of a Post article discussing the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would conclude. The piece includes assertions from two experts, David Stevens, president of the Mortgage Bankers Association, and Julia Gordon, the director of housing finance and policy at the Center for American Progress, that 30-year fixed rate mortgages would disappear if the government did not guarantee these mortgages through the GSEs or some other mechanism.

This can easily be shown not to be true by the market in jumbo mortgages. These are mortgages that are too large in value to be insured by the GSEs. A large share of these mortgages are 30-year fixed rate mortgages. Also, while it is less common today, prior to the housing bubble banks did hold a substantial share of their mortgages, typically around 10-20 percent. Since the government was not guaranteeing these mortgages, the banks must have felt the guarantee was unnecessary to get them to issue 30-year fixed rate mortgages.

The issue with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is one of the interest rates that people will pay on mortgages, not whether they will exist or not. By having a government guarantee the government is providing a subsidy to homebuyers that comes at the expense of the rest of the economy. The government already provides a subsidy to homebuyers through the mortgage interest deduction, the question is whether it is desirable to provide a further subsidy through this government guarantee.

There is also a question of whether this is the most efficient way to provide the subsidy. The government guarantee can set up a complex system of financial intermediaries that may be difficult to regulate. It may be more efficient to provide any additional subsidy to homeownership through an enhanced tax deduction or credit that would not lead to a bloated financial sector.

These are the issues that should be at the center of the debate over the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Post should have been able to recognize the absurdity of claims about the end of 30-year fixed rate mortgages and have found an expert to clarify this point.

Note: Corrected acronym to “GSE.” Thanks to David Stevens.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Brad Plummer has a useful post showing that with current policy in place we can keep CO2 emissions constant over the next three decades. The piece notes that this would be inadequate to prevent dangerous levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere; for that we would need substantial reductions in emissions.

It is worth calling attention to one comment that may mislead readers. At one point the piece tells readers:

“Some of these measures [continuing current policy], such as re-upping the tax credits for clean energy, would require Congress. (And that wouldn’t be free; the recent one-year extension of the wind credit, for instance, will cost $1.2 billion per year for 10 years.)”

It’s unlikely that many readers have a clear sense of how much money $1.2 billion a year is relative to the budget. Spending is projected to average more than $4.7 trillion a year over the next decade. This means that the extension of the clean energy credits would cost less than 0.03 percent of projected spending. This likely would provide more information to readers than the dollar amount.

Brad Plummer has a useful post showing that with current policy in place we can keep CO2 emissions constant over the next three decades. The piece notes that this would be inadequate to prevent dangerous levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere; for that we would need substantial reductions in emissions.

It is worth calling attention to one comment that may mislead readers. At one point the piece tells readers:

“Some of these measures [continuing current policy], such as re-upping the tax credits for clean energy, would require Congress. (And that wouldn’t be free; the recent one-year extension of the wind credit, for instance, will cost $1.2 billion per year for 10 years.)”

It’s unlikely that many readers have a clear sense of how much money $1.2 billion a year is relative to the budget. Spending is projected to average more than $4.7 trillion a year over the next decade. This means that the extension of the clean energy credits would cost less than 0.03 percent of projected spending. This likely would provide more information to readers than the dollar amount.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión