As its readers know, the Washington Post really really wants to see big cuts in Medicare and Social Security and is happy to use its news pages to advance this agenda. In a budget piece today, it told readers:

“In a flurry of meetings and phone calls over the past few days, Obama has courted more than half a dozen Republicans in the Senate, telling them that he is ready to overhaul expensive health and retirement programs if they agree to raise taxes to tame the national debt” [emphasis added].

If the Post was not trying to push its Big Deal agenda, it would have told readers that Obama is willing to cut health care retirement programs. The issue here is reducing government payments, not changing the color of the forms used. It also would not use the adjective “expensive.” While the country does pay a lot of money for Medicare and Medicaid, because it pays doctors and other providers much more than they get elsewhere, Social Security is actually relatively cheap compared to other countries’ public pension programs.

Also, an objective newspaper would not have inserted the word “tame” since the data do not support the case that the debt is somehow out of control. The ratio of debt to GDP has been rising only because the collapse of the housing bubble led to a severe downturn. Had it not been for this downturn, the ratio would have fallen through most of the decade. The ratio of interest to GDP is near a post-war low.

The piece also asserts that:

“there was more skepticism of Obama’s motives”

among many Republicans. Of course the Post does not know whether Republicans really were skeptical of President Obama’s motives, they just know that Republicans claimed to be skeptical. It is not good reporting to accept assertions from politicians at face value, since they are not always truthful.

As its readers know, the Washington Post really really wants to see big cuts in Medicare and Social Security and is happy to use its news pages to advance this agenda. In a budget piece today, it told readers:

“In a flurry of meetings and phone calls over the past few days, Obama has courted more than half a dozen Republicans in the Senate, telling them that he is ready to overhaul expensive health and retirement programs if they agree to raise taxes to tame the national debt” [emphasis added].

If the Post was not trying to push its Big Deal agenda, it would have told readers that Obama is willing to cut health care retirement programs. The issue here is reducing government payments, not changing the color of the forms used. It also would not use the adjective “expensive.” While the country does pay a lot of money for Medicare and Medicaid, because it pays doctors and other providers much more than they get elsewhere, Social Security is actually relatively cheap compared to other countries’ public pension programs.

Also, an objective newspaper would not have inserted the word “tame” since the data do not support the case that the debt is somehow out of control. The ratio of debt to GDP has been rising only because the collapse of the housing bubble led to a severe downturn. Had it not been for this downturn, the ratio would have fallen through most of the decade. The ratio of interest to GDP is near a post-war low.

The piece also asserts that:

“there was more skepticism of Obama’s motives”

among many Republicans. Of course the Post does not know whether Republicans really were skeptical of President Obama’s motives, they just know that Republicans claimed to be skeptical. It is not good reporting to accept assertions from politicians at face value, since they are not always truthful.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I see that Brad has a post saying that the economy was adjusting nicely to the bursting of the housing bubble until the financial crisis set in. He notes that housing construction fell by 2.5 percentage points of GDP between 2005 and 2008. This was replaced by an increase in gross exports of 2.0 pp of GDP and increase in equipment investment of 0.5 pp. Everything was moving along nicely until the financial crisis in 2008.

I see things a bit differently. First, gross exports don’t create jobs, net exports do. When we move an auto assembly plant from Ohio to Mexico, we are not creating additional jobs with the car parts exported to Mexico. That’s intro textbook stuff. If we look at the net export picture, the gain is only about 1 pp of GDP. Furthermore, it is hard to see the improvement in the trade picture having gone very much further without a further decline in the dollar. (That was a possibility, but far from a certainty — it depends on policy decisions elsewhere.)

The rest of the gap was made up by a surge in non-residential construction (can you say bubble?), which rose by more than 33 percent as a share of GDP, or more than 1 pp of GDP. This boom led to considerable overbuilding in retail, office space and most other categories of non-residential construction. Assuming the burst of spending in non-residential construction was another bubble, then the portion of the demand gap filled through this channel was destined to be temporary. It was inevitable that this bubble would also burst and we would need something else to make up the hole in demand.

The other factor in the mix is the drop off in consumption. Savings rates had been driven to nearly zero by the wealth created by the housing bubble. It seems to me inevitable that consumption would fall in response to the disappearance of this wealth. The financial crisis gave us a Wily E. Coyote moment where everyone stopped spending at the same time, but I would argue that this just brought the decline in spending forward in time.

The savings rate remains much higher today than at the peak of the bubble, although still low by historic standards. (It’s currently around 4.0 percent, the pre-bubble average was over 8.0 percent.) We have two alternative hypotheses here. I gather Brad would say that people are spending at a lower rate because they are still freaked out by the financial crisis. I would argue that they are spending at a lower rate for the same reason that homeless people don’t spend, they don’t have the money.

Homeowners are down $8 trillion in housing equity as a result of the crash. I would expect that loss of wealth to have a substantial impact on their spending. I gather Brad does not.

[Correction: The earlier version said “net exports” in the first paragraph.]

I see that Brad has a post saying that the economy was adjusting nicely to the bursting of the housing bubble until the financial crisis set in. He notes that housing construction fell by 2.5 percentage points of GDP between 2005 and 2008. This was replaced by an increase in gross exports of 2.0 pp of GDP and increase in equipment investment of 0.5 pp. Everything was moving along nicely until the financial crisis in 2008.

I see things a bit differently. First, gross exports don’t create jobs, net exports do. When we move an auto assembly plant from Ohio to Mexico, we are not creating additional jobs with the car parts exported to Mexico. That’s intro textbook stuff. If we look at the net export picture, the gain is only about 1 pp of GDP. Furthermore, it is hard to see the improvement in the trade picture having gone very much further without a further decline in the dollar. (That was a possibility, but far from a certainty — it depends on policy decisions elsewhere.)

The rest of the gap was made up by a surge in non-residential construction (can you say bubble?), which rose by more than 33 percent as a share of GDP, or more than 1 pp of GDP. This boom led to considerable overbuilding in retail, office space and most other categories of non-residential construction. Assuming the burst of spending in non-residential construction was another bubble, then the portion of the demand gap filled through this channel was destined to be temporary. It was inevitable that this bubble would also burst and we would need something else to make up the hole in demand.

The other factor in the mix is the drop off in consumption. Savings rates had been driven to nearly zero by the wealth created by the housing bubble. It seems to me inevitable that consumption would fall in response to the disappearance of this wealth. The financial crisis gave us a Wily E. Coyote moment where everyone stopped spending at the same time, but I would argue that this just brought the decline in spending forward in time.

The savings rate remains much higher today than at the peak of the bubble, although still low by historic standards. (It’s currently around 4.0 percent, the pre-bubble average was over 8.0 percent.) We have two alternative hypotheses here. I gather Brad would say that people are spending at a lower rate because they are still freaked out by the financial crisis. I would argue that they are spending at a lower rate for the same reason that homeless people don’t spend, they don’t have the money.

Homeowners are down $8 trillion in housing equity as a result of the crash. I would expect that loss of wealth to have a substantial impact on their spending. I gather Brad does not.

[Correction: The earlier version said “net exports” in the first paragraph.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s extremely unfair that shoe salespeople have to pay taxes on their income at the same rate as other workers. After all, they must work with shoe buyers, achieve an alignment of interest, and then get them to buy the shoes. Clearly this means that they should be taxed at the lower capital gains rate rather than the ordinary earnings rate that factory workers and school teachers pay.

Yes, this is nuts, but because very rich people run pension and hedge funds, the NYT feels the need to treat this stuff seriously. Therefore it gave Steve Judge, the chief executive of the Private Equity Growth Capital Council the opportunity to say that shoes salespeople shouldn’t have to be taxed at the same rate as everyone else. (Sorry, I meant rich equity and hedge fund managers.)

This one does not come close to passing the laugh test. The point here is very simple. When you get paid for work, whether you are school teacher, a shoe salesperson, or a hedge fund manager, this is earned income and should be taxed as such.

If hedge and private equity fund managers want to invest in their funds they are free to do so and can have their subsequent income taxed at the lower capital gains rate. This is really simple — even a hedge fund or private equity fund manager should be able to understand this. It is not a complicated issue no matter how much people may get paid to make it complicated.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Tom.

It’s extremely unfair that shoe salespeople have to pay taxes on their income at the same rate as other workers. After all, they must work with shoe buyers, achieve an alignment of interest, and then get them to buy the shoes. Clearly this means that they should be taxed at the lower capital gains rate rather than the ordinary earnings rate that factory workers and school teachers pay.

Yes, this is nuts, but because very rich people run pension and hedge funds, the NYT feels the need to treat this stuff seriously. Therefore it gave Steve Judge, the chief executive of the Private Equity Growth Capital Council the opportunity to say that shoes salespeople shouldn’t have to be taxed at the same rate as everyone else. (Sorry, I meant rich equity and hedge fund managers.)

This one does not come close to passing the laugh test. The point here is very simple. When you get paid for work, whether you are school teacher, a shoe salesperson, or a hedge fund manager, this is earned income and should be taxed as such.

If hedge and private equity fund managers want to invest in their funds they are free to do so and can have their subsequent income taxed at the lower capital gains rate. This is really simple — even a hedge fund or private equity fund manager should be able to understand this. It is not a complicated issue no matter how much people may get paid to make it complicated.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Tom.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers of Marc Thiessen’s column on the sequester would conclude. Theissen repeatedly touts the report of the Bowles-Simpson commission. Of course there was no report issued by the commission because no report received the necessary majority. The Post’s fact checkers would have quickly caught Thiessen’s error and insist that he correct it, but such is the price of labor discord.

Thiessen’s piece is also striking for the lack of concern for the people will lose their jobs as a result of slower growth that is resulting from his preferred policy. Presumably he does not imagine himself or his friends to be among the people who will lose jobs because of the policies he advocates.

That’s what readers of Marc Thiessen’s column on the sequester would conclude. Theissen repeatedly touts the report of the Bowles-Simpson commission. Of course there was no report issued by the commission because no report received the necessary majority. The Post’s fact checkers would have quickly caught Thiessen’s error and insist that he correct it, but such is the price of labor discord.

Thiessen’s piece is also striking for the lack of concern for the people will lose their jobs as a result of slower growth that is resulting from his preferred policy. Presumably he does not imagine himself or his friends to be among the people who will lose jobs because of the policies he advocates.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post began an article on a meeting of the euro zone finance ministers by telling readers:

“European leaders demanded that euro members press on with budget cuts to end the debt crisis.”

At this point there is overwhelming evidence that the primary effect of the austerity being demanded by the finance ministers is to slow growth and increase unemployment. As a result of the negative impact on output, the budget cuts lead to little improvement in the financial situation of the affected countries.

Since the evidence shows that the ministers’ austerity agenda is not an effective way to deal with the debt crisis it is wrong of the Post to tell readers that this is the motive of the finance ministers. This assertion assumes that the finance ministers have no clue about the actual effect of the policies they advocate. While this may in fact be true, the Post certainly cannot claim to know that the euro zone’s finance ministers are completely clueless about economics.

It would have been more accurate to simply report what the ministers claim, for example writing:

“European leaders demanded that euro members press on with budget cuts ‘to end the debt crisis.'”

This would made have made it clear to readers that the rationale claimed by the finance ministers bears no obvious relation to reality.

The Washington Post began an article on a meeting of the euro zone finance ministers by telling readers:

“European leaders demanded that euro members press on with budget cuts to end the debt crisis.”

At this point there is overwhelming evidence that the primary effect of the austerity being demanded by the finance ministers is to slow growth and increase unemployment. As a result of the negative impact on output, the budget cuts lead to little improvement in the financial situation of the affected countries.

Since the evidence shows that the ministers’ austerity agenda is not an effective way to deal with the debt crisis it is wrong of the Post to tell readers that this is the motive of the finance ministers. This assertion assumes that the finance ministers have no clue about the actual effect of the policies they advocate. While this may in fact be true, the Post certainly cannot claim to know that the euro zone’s finance ministers are completely clueless about economics.

It would have been more accurate to simply report what the ministers claim, for example writing:

“European leaders demanded that euro members press on with budget cuts ‘to end the debt crisis.'”

This would made have made it clear to readers that the rationale claimed by the finance ministers bears no obvious relation to reality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT yet again referred to a report of the Bowles-Simpson Commission. There is no report from the Bowles-Simpson Commission because no report received the support of the necessary majority.

All of the sources for this article indicate that they want to see cuts in Social Security and Medicare. This is a position that is opposed by the vast majority of people regardless of their political party or ideology. It would be useful if the NYT did not exclusively present the views of the minority who want to see cuts in these programs in its budget articles.

The NYT yet again referred to a report of the Bowles-Simpson Commission. There is no report from the Bowles-Simpson Commission because no report received the support of the necessary majority.

All of the sources for this article indicate that they want to see cuts in Social Security and Medicare. This is a position that is opposed by the vast majority of people regardless of their political party or ideology. It would be useful if the NYT did not exclusively present the views of the minority who want to see cuts in these programs in its budget articles.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

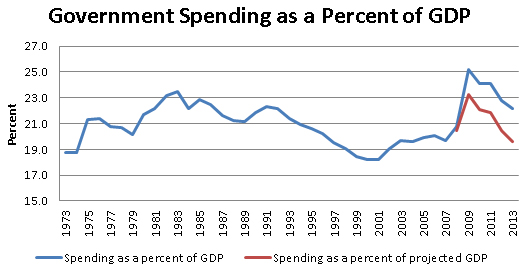

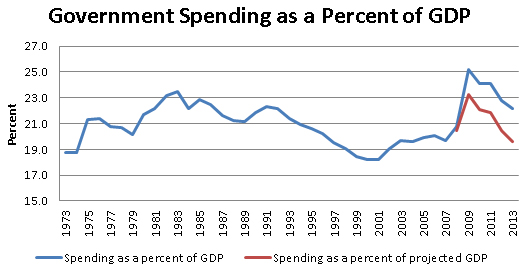

It would have been helpful if the NYT had pointed out this fact in an article that included assertions from House Speaker John Boehner that spending is out of control.

“The president got his tax hikes on January the First. The issue here is spending. Spending is out of control.”

In fact, spending as a share of potential GDP is near a 30-year low and is lower than at any point in the Reagan-Bush I administrations. The chart shows federal spending as a share of GDP and as a share of the GDP projected by the Congressional Budget Office in 2008 before it recognized the impact of the collapse of the housing bubble.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

It would have been helpful to remind readers of the actual path of government spending since many may not have not realized that Boehner was not being truthful.

It would have been helpful if the NYT had pointed out this fact in an article that included assertions from House Speaker John Boehner that spending is out of control.

“The president got his tax hikes on January the First. The issue here is spending. Spending is out of control.”

In fact, spending as a share of potential GDP is near a 30-year low and is lower than at any point in the Reagan-Bush I administrations. The chart shows federal spending as a share of GDP and as a share of the GDP projected by the Congressional Budget Office in 2008 before it recognized the impact of the collapse of the housing bubble.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

It would have been helpful to remind readers of the actual path of government spending since many may not have not realized that Boehner was not being truthful.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión