It seems pretty obvious to most of us that politicians get elected by appealing to powerful interest groups. They spend enormous amounts of time calling up rich people to ask for campaign donations and speaking to individuals who can help to deliver large numbers of votes. This is hardly a secret.

Yet, the New York Times again tries to tell us that these people are really philosophers, telling readers in a headline:

“Deep philosophical divide underlies the impasse”

in reference to the budget sequester.

The piece explains to readers:

“a step back illuminates roots deeper than the prevailing notion that Washington politicians are simply fools acting for electoral advantage or partisan spite. Republicans don’t seek to grind government to a halt. But they do aim to shrink its size by an amount currently beyond their institutional power in Washington, or popular support in the country, to achieve.

“Democrats don’t seek to cripple the nation with debt. But they do aim to preserve existing government programs without the ability, so far, to set levels of taxation commensurate with their cost.

“At bottom, it is the oldest philosophic battle of the American party system — pitting Democrats’ desire to use government to cushion market outcomes and equalize opportunity against Republicans’ desire to limit government and maximize individual liberty.”

Really, this is a battle of philosophy?

Let’s try an alternative explanation. Let’s assume that Republicans answer to rich people who don’t want to pay a dime more in taxes and would actually prefer to pay many dimes less. Let’s imagine that these people are not stupid and that they understand completely what conservative economists like Greg Mankiw, Martin Feldstein and Alan Greenspan have been telling them for years, tax expenditures are a form of spending. In other words, if we give someone a housing subsidy of $5,000 a year by cutting their taxes by this amount if they buy a home, it is the same thing as if the government sends them a check that says “housing subsidy.”

If we take the philosophy view of this debate then Republicans would be all for eliminating the tax expenditures that mostly go to line the pockets of rich people. On the other hand, if we think this is a debate about whose pockets get lined then Republicans who are opposed to spending would be opposed to eliminating tax expenditures for rich people.

Neither we nor the NYT know which explanation is true. But the NYT explanation requires that the politicians who oppose cuts in tax expenditures and/or their backers are stupid. They may be, or the NYT may just be wrong and badly misinforming its readers.

Thanks to Keane Bhatt for calling this one to my attention.

It seems pretty obvious to most of us that politicians get elected by appealing to powerful interest groups. They spend enormous amounts of time calling up rich people to ask for campaign donations and speaking to individuals who can help to deliver large numbers of votes. This is hardly a secret.

Yet, the New York Times again tries to tell us that these people are really philosophers, telling readers in a headline:

“Deep philosophical divide underlies the impasse”

in reference to the budget sequester.

The piece explains to readers:

“a step back illuminates roots deeper than the prevailing notion that Washington politicians are simply fools acting for electoral advantage or partisan spite. Republicans don’t seek to grind government to a halt. But they do aim to shrink its size by an amount currently beyond their institutional power in Washington, or popular support in the country, to achieve.

“Democrats don’t seek to cripple the nation with debt. But they do aim to preserve existing government programs without the ability, so far, to set levels of taxation commensurate with their cost.

“At bottom, it is the oldest philosophic battle of the American party system — pitting Democrats’ desire to use government to cushion market outcomes and equalize opportunity against Republicans’ desire to limit government and maximize individual liberty.”

Really, this is a battle of philosophy?

Let’s try an alternative explanation. Let’s assume that Republicans answer to rich people who don’t want to pay a dime more in taxes and would actually prefer to pay many dimes less. Let’s imagine that these people are not stupid and that they understand completely what conservative economists like Greg Mankiw, Martin Feldstein and Alan Greenspan have been telling them for years, tax expenditures are a form of spending. In other words, if we give someone a housing subsidy of $5,000 a year by cutting their taxes by this amount if they buy a home, it is the same thing as if the government sends them a check that says “housing subsidy.”

If we take the philosophy view of this debate then Republicans would be all for eliminating the tax expenditures that mostly go to line the pockets of rich people. On the other hand, if we think this is a debate about whose pockets get lined then Republicans who are opposed to spending would be opposed to eliminating tax expenditures for rich people.

Neither we nor the NYT know which explanation is true. But the NYT explanation requires that the politicians who oppose cuts in tax expenditures and/or their backers are stupid. They may be, or the NYT may just be wrong and badly misinforming its readers.

Thanks to Keane Bhatt for calling this one to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A fortune teller who is constantly adjusting his predictions for the future when they are repeatedly falsified by events is likely to lose credibility after a while. Unfortunately the same does not hold true among economists. That is why a Washington Post article on the prospects for future growth treats the varying perspectives among economists as carrying equal weight.

Some of the economists have had their predictions for the economy repeatedly falsified by events, starting with the initial crash which they never thought possible. Some in this camp now insist that we are on a permanently slower growth path. This prediction is a sequel to their earlier prediction that the economy would bounce back quickly even without any special boost from fiscal or monetary policy. There were also many orthodox mainstream economists who, like those at the Congressional Budget Office, also expected the economy to bounce back quickly whether or not there was a boost from government stimulus.

On the other hand, at least some of us Keynesian types saw the housing bubble and yelled at the top of our lungs that it would collapse and bring about a severe recession. We also warned that demand would not bounce back quickly since there was nothing to replace the construction and consumption demand generated by the bubble. And we pointed out that we would not be likely to see deflation since wages are sticky downward.

In all of these predications were we shown right, but in Washington policy debates being shown right counts for little as the Washington Post tells us today.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for corrected typos.

A fortune teller who is constantly adjusting his predictions for the future when they are repeatedly falsified by events is likely to lose credibility after a while. Unfortunately the same does not hold true among economists. That is why a Washington Post article on the prospects for future growth treats the varying perspectives among economists as carrying equal weight.

Some of the economists have had their predictions for the economy repeatedly falsified by events, starting with the initial crash which they never thought possible. Some in this camp now insist that we are on a permanently slower growth path. This prediction is a sequel to their earlier prediction that the economy would bounce back quickly even without any special boost from fiscal or monetary policy. There were also many orthodox mainstream economists who, like those at the Congressional Budget Office, also expected the economy to bounce back quickly whether or not there was a boost from government stimulus.

On the other hand, at least some of us Keynesian types saw the housing bubble and yelled at the top of our lungs that it would collapse and bring about a severe recession. We also warned that demand would not bounce back quickly since there was nothing to replace the construction and consumption demand generated by the bubble. And we pointed out that we would not be likely to see deflation since wages are sticky downward.

In all of these predications were we shown right, but in Washington policy debates being shown right counts for little as the Washington Post tells us today.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for corrected typos.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Michael Gerson is upset that Democrats didn’t want to have a debt clock shown at a hearing of the Senate Finance Committee. He huffs:

“numbers, it turns out, have an offensive ideological bias.”

I’m sympathetic. Right alongside the debt clock we could have the lost output clock. If we use the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) measure of potential GDP, this would be rising at the rate of about $3 billion a day or $1 trillion a year. If we used CBO’s 2008 economic projections as the basis for measuring lost output, then the clock would be rising at a rate of more than $5 billion a day, more than $1.6 trillion a year. This of course is a huge understatement since it doesn’t pick up costs like alcoholism, suicides, and family break-ups that are indirect outcomes of unemployment.

Presumably Gerson supports having this lost output clock, right? After all, numbers can’t have an ideological bias.

Gerson’s real complaint is that we haven’t solved problems that may occur in the decade of the 2020s, if it turns out that health care costs are still out of control. If health care costs are under control (as recent data suggest may be the case), then these problems will not exist. Of course the answer to out of control health care costs is to fix the health care system, not run around yelling about budget deficits.

Maybe we can give Gerson a clock measuring the number of ants that have crossed national boundaries anywhere in the world. It wouldn’t really have much to do with anything, but then neither does his beloved debt clock.

Michael Gerson is upset that Democrats didn’t want to have a debt clock shown at a hearing of the Senate Finance Committee. He huffs:

“numbers, it turns out, have an offensive ideological bias.”

I’m sympathetic. Right alongside the debt clock we could have the lost output clock. If we use the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) measure of potential GDP, this would be rising at the rate of about $3 billion a day or $1 trillion a year. If we used CBO’s 2008 economic projections as the basis for measuring lost output, then the clock would be rising at a rate of more than $5 billion a day, more than $1.6 trillion a year. This of course is a huge understatement since it doesn’t pick up costs like alcoholism, suicides, and family break-ups that are indirect outcomes of unemployment.

Presumably Gerson supports having this lost output clock, right? After all, numbers can’t have an ideological bias.

Gerson’s real complaint is that we haven’t solved problems that may occur in the decade of the 2020s, if it turns out that health care costs are still out of control. If health care costs are under control (as recent data suggest may be the case), then these problems will not exist. Of course the answer to out of control health care costs is to fix the health care system, not run around yelling about budget deficits.

Maybe we can give Gerson a clock measuring the number of ants that have crossed national boundaries anywhere in the world. It wouldn’t really have much to do with anything, but then neither does his beloved debt clock.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is worth reading (that’s true of almost all of Johnson’s posts). It highlights growing recognition of the too big to fail subsidy enjoyed by large banks and evidence of bipartisan efforts to end it. Just to remind folks that may have forgotten, a bloated financial sector is a drain on the economy in the same way as that huge government department of waste, fraud, and abuse that everyone in Washington is looking for. It also is a source of instability and a major generator of inequality. And, by the way, when it comes to estimating the size of big bank subsidies, CEPR got there first.

This is worth reading (that’s true of almost all of Johnson’s posts). It highlights growing recognition of the too big to fail subsidy enjoyed by large banks and evidence of bipartisan efforts to end it. Just to remind folks that may have forgotten, a bloated financial sector is a drain on the economy in the same way as that huge government department of waste, fraud, and abuse that everyone in Washington is looking for. It also is a source of instability and a major generator of inequality. And, by the way, when it comes to estimating the size of big bank subsidies, CEPR got there first.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece discussing views in the Czech Republic on joining the euro. It left the issue very much as a he said, she said, providing little information that could provide readers with a basis for assessing the merits of the policy. While the piece did report the Czech Republic’s unemployment rate as 7.5 percent, indicating it has not escaped the effects of the euro crisis, it would have been a simple matter to compare the change in unemployment from the pre-crisis years.

In the Czech case, the rise was 3.1 percentage points from a 2008 unemployment rate of 4.4 percent. The rise in the euro zone as a whole was 4.1 percentage points to 11.7 percent. The rise in the unemployment rate in the peripheral countries like Spain and Greece, which may provide a more appropriate comparison, was in the double digits. This may suggest that the Czech Republic benefited substantially as a result of the fact that it was not tied to the euro and the European Central Bank.

Addendum:

Okay folks, here’s the data. According to the IMF, the Czech Republic had a per capita GDP in 2007 of $25,300. In Greece it was $28,600 and Spain $30,200. By comparison, per capita GDP in Austria was $38,600 and in Germany it was $34,600. If you think the Czech economy is more like Austria and Germany’s than Greece’s and Spain’s then you better go straighten out the folks who compile the data at the IMF.

The NYT had a piece discussing views in the Czech Republic on joining the euro. It left the issue very much as a he said, she said, providing little information that could provide readers with a basis for assessing the merits of the policy. While the piece did report the Czech Republic’s unemployment rate as 7.5 percent, indicating it has not escaped the effects of the euro crisis, it would have been a simple matter to compare the change in unemployment from the pre-crisis years.

In the Czech case, the rise was 3.1 percentage points from a 2008 unemployment rate of 4.4 percent. The rise in the euro zone as a whole was 4.1 percentage points to 11.7 percent. The rise in the unemployment rate in the peripheral countries like Spain and Greece, which may provide a more appropriate comparison, was in the double digits. This may suggest that the Czech Republic benefited substantially as a result of the fact that it was not tied to the euro and the European Central Bank.

Addendum:

Okay folks, here’s the data. According to the IMF, the Czech Republic had a per capita GDP in 2007 of $25,300. In Greece it was $28,600 and Spain $30,200. By comparison, per capita GDP in Austria was $38,600 and in Germany it was $34,600. If you think the Czech economy is more like Austria and Germany’s than Greece’s and Spain’s then you better go straighten out the folks who compile the data at the IMF.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I hate to have to correct Nobel prize winners (okay, that’s not true), but Robert Solow does get one item somewhat wrong in an otherwise useful column on the government’s debt. Solow notes that close to half of the publicly held debt is owned by foreigners. He then tells readers:

“This part of the debt is a direct burden on ourselves and future generations. Foreigners are entitled to receive interest and principal and can use those dollars to acquire goods and services produced here. If our government had used borrowed money to improve infrastructure or to improve the skills of workers, the resulting extra production would have made repayment easier. Instead, over the last decade, it used the money for wars and tax cuts.”

This is somewhat misleading. Suppose that the United States had been running balanced budgets for the last three decades, so there was little or no public debt for foreigners to buy, but we had run the same trade deficits over this period. In this case, foreigners would own the same amount of U.S. assets, except they would be private assets like stocks, bonds, and real estate. The income from these assets would be:

“a direct burden on ourselves and future generations. Foreigners are entitled to receive interest and principal and can use those dollars to acquire goods and services produced here.”

In other words, the fact that we have given foreigners a substantial claim to our future income is the result of our trade deficits, not our budget deficits.

There is an argument that the budget deficit has contributed to the trade deficit, but it is not as simple as many people in policy debates seem to believe. If a budget deficit provides a boost to the economy, as the stimulus did in 2009-2010, then it will increase the trade deficit. The logic here is simple. If the economy is bigger, then we buy more of everything, including more imports.

In this argument, if we cut our budget deficit, we can reduce our borrowing from abroad by shrinking the economy. This is true, but it seems like a rather dubious argument. Do we really want to have millions more people out of work just so that we can deny foreigners a share of our future income? It is also worth noting that an increase in private sector investment or consumption would have the same impact in increasing the trade deficit.

When the economy is below full employment, anything that raises GDP will lead us to purchase more imports. This includes budget deficits.

The other way in which the budget deficit can lead to a higher trade deficit is by causing the dollar to rise. The logic here is usually that larger budget deficits mean higher interest rates, which in turn will raise the value of the dollar. However the exact mechanism does not matter, the point is that the proximate cause of the larger trade deficit is a higher valued dollar, not the budget deficit. If the deficit does not cause the dollar to rise, then it would not have an impact on the trade deficit.

The other implication of this line of reasoning is that if we are concerned about our growing indebtedness to foreigners then we should be concerned about the over-valuation of the dollar. Whatever steps we take to reduce the value of the dollar will increase the competitiveness of U.S. goods, reducing imports and increasing exports. This means that those who are troubled by the extent to which foreigners will have a claim on future income should be concerned about the value of the dollar, not the budget deficit.

If we lower the budget deficit without lowering the value of the dollar, then it will not improve our trade deficit (except to the extent that the lower deficit reduces GDP). On the other hand, if we can lower the value of the dollar without reducing the budget deficit then we will have addressed the concern about foreigners buying up U.S. assets and thereby getting claims to future income.

Note: Typo corrected — thanks John.

I hate to have to correct Nobel prize winners (okay, that’s not true), but Robert Solow does get one item somewhat wrong in an otherwise useful column on the government’s debt. Solow notes that close to half of the publicly held debt is owned by foreigners. He then tells readers:

“This part of the debt is a direct burden on ourselves and future generations. Foreigners are entitled to receive interest and principal and can use those dollars to acquire goods and services produced here. If our government had used borrowed money to improve infrastructure or to improve the skills of workers, the resulting extra production would have made repayment easier. Instead, over the last decade, it used the money for wars and tax cuts.”

This is somewhat misleading. Suppose that the United States had been running balanced budgets for the last three decades, so there was little or no public debt for foreigners to buy, but we had run the same trade deficits over this period. In this case, foreigners would own the same amount of U.S. assets, except they would be private assets like stocks, bonds, and real estate. The income from these assets would be:

“a direct burden on ourselves and future generations. Foreigners are entitled to receive interest and principal and can use those dollars to acquire goods and services produced here.”

In other words, the fact that we have given foreigners a substantial claim to our future income is the result of our trade deficits, not our budget deficits.

There is an argument that the budget deficit has contributed to the trade deficit, but it is not as simple as many people in policy debates seem to believe. If a budget deficit provides a boost to the economy, as the stimulus did in 2009-2010, then it will increase the trade deficit. The logic here is simple. If the economy is bigger, then we buy more of everything, including more imports.

In this argument, if we cut our budget deficit, we can reduce our borrowing from abroad by shrinking the economy. This is true, but it seems like a rather dubious argument. Do we really want to have millions more people out of work just so that we can deny foreigners a share of our future income? It is also worth noting that an increase in private sector investment or consumption would have the same impact in increasing the trade deficit.

When the economy is below full employment, anything that raises GDP will lead us to purchase more imports. This includes budget deficits.

The other way in which the budget deficit can lead to a higher trade deficit is by causing the dollar to rise. The logic here is usually that larger budget deficits mean higher interest rates, which in turn will raise the value of the dollar. However the exact mechanism does not matter, the point is that the proximate cause of the larger trade deficit is a higher valued dollar, not the budget deficit. If the deficit does not cause the dollar to rise, then it would not have an impact on the trade deficit.

The other implication of this line of reasoning is that if we are concerned about our growing indebtedness to foreigners then we should be concerned about the over-valuation of the dollar. Whatever steps we take to reduce the value of the dollar will increase the competitiveness of U.S. goods, reducing imports and increasing exports. This means that those who are troubled by the extent to which foreigners will have a claim on future income should be concerned about the value of the dollar, not the budget deficit.

If we lower the budget deficit without lowering the value of the dollar, then it will not improve our trade deficit (except to the extent that the lower deficit reduces GDP). On the other hand, if we can lower the value of the dollar without reducing the budget deficit then we will have addressed the concern about foreigners buying up U.S. assets and thereby getting claims to future income.

Note: Typo corrected — thanks John.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

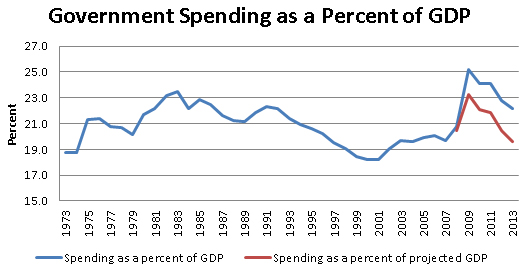

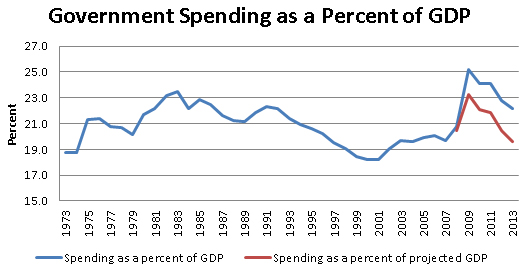

I know it’s rude to bring numbers to DC policy debates, but some of us uncouth types just can’t control ourselves. Just for fun, I thought I would see what government spending measured as a share of GDP would look like if the economy had grown as had been projected before the 2008 collapse.

This is similar to taking the deficits as a share of potential GDP, but not exactly the same. Potential GDP is based on the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) estimate of the economy’s potential level of output. I am looking at the levels of GDP that CBO projected back in January of 2008 (Table 2-1), before it recognized the impact that the collapse of the housing bubble would have on the economy.

The estimate of potential GDP will differ for three reasons. First CBO may just be wrong about the economy’s potential, it could be higher or lower than the level they estimate. Second, potential GDP may be lower as a result of economic developments over the last five years. For example, the large number of workers who have experienced long periods of unemployment may have effectively reduced the size of our potential labor force as some have lost skills. Third, CBO may just have been out to lunch when they made their projections in 2008.

In any case, this is still a useful exercise. It gives a chance to see the extent to which the ratio of spending to GDP has increased as a result of the fact that we are spending more than we had in 2007 relative to the size of the economy as opposed to the fact that the economy did not grow as much as we expected. Here’s the picture:

Source: CBO and author’s calculations.

CBO projects that spending will be 22.8 percent of GDP in fiscal 2013 (this includes the effects of the sequester). That puts spending above the average of the last four decades, but below the peaks reached in the Reagan years. However, if the economy had grown at the rate that was projected in 2008, the current year’s spending would be just 19.6 percent of GDP. That puts 2013 spending well below the 20.7 percent of GDP average for the years from 1973-2007. That is especially striking since we know that Medicare and Social Security have grown substantially as a share GDP due to the aging of the population.

So where is the runaway spending? Oh well, this is Washington. Let’s get back to the sequester.

I know it’s rude to bring numbers to DC policy debates, but some of us uncouth types just can’t control ourselves. Just for fun, I thought I would see what government spending measured as a share of GDP would look like if the economy had grown as had been projected before the 2008 collapse.

This is similar to taking the deficits as a share of potential GDP, but not exactly the same. Potential GDP is based on the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) estimate of the economy’s potential level of output. I am looking at the levels of GDP that CBO projected back in January of 2008 (Table 2-1), before it recognized the impact that the collapse of the housing bubble would have on the economy.

The estimate of potential GDP will differ for three reasons. First CBO may just be wrong about the economy’s potential, it could be higher or lower than the level they estimate. Second, potential GDP may be lower as a result of economic developments over the last five years. For example, the large number of workers who have experienced long periods of unemployment may have effectively reduced the size of our potential labor force as some have lost skills. Third, CBO may just have been out to lunch when they made their projections in 2008.

In any case, this is still a useful exercise. It gives a chance to see the extent to which the ratio of spending to GDP has increased as a result of the fact that we are spending more than we had in 2007 relative to the size of the economy as opposed to the fact that the economy did not grow as much as we expected. Here’s the picture:

Source: CBO and author’s calculations.

CBO projects that spending will be 22.8 percent of GDP in fiscal 2013 (this includes the effects of the sequester). That puts spending above the average of the last four decades, but below the peaks reached in the Reagan years. However, if the economy had grown at the rate that was projected in 2008, the current year’s spending would be just 19.6 percent of GDP. That puts 2013 spending well below the 20.7 percent of GDP average for the years from 1973-2007. That is especially striking since we know that Medicare and Social Security have grown substantially as a share GDP due to the aging of the population.

So where is the runaway spending? Oh well, this is Washington. Let’s get back to the sequester.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión