Just wondering, since Thomas Friedman says there are 400 million bloggers in China.

Just wondering, since Thomas Friedman says there are 400 million bloggers in China.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Tyler Cowan argues in his column today that we should let the sequester cuts go into effect but his argument is a bit hard to follow. He tells readers:

“One common argument against letting this process run its course is a Keynesian claim — namely, that cuts or slowdowns in government spending can throw an economy into recession by lowering total demand for goods and services. Nonetheless, spending cuts of the right kind can help an economy.”

He then goes on to point out that we can have cuts in military spending, farm subsidies and other areas that could benefit the economy.

This is where the story gets confusing. If we are looking to Keynes then the argument is straightforward, if we make cuts to the budget in a period of high unemployment like the present, then we are throwing more people out of work. These people will not be re-employed elsewhere, or if they are, they will be displacing other workers. (Btw, it’s not clear why the word “recession” appears in the paragraph. The point is simply that we would have slower growth and fewer jobs, there is no magic recession threshold in any Keynesian text I have seen.)

This Keynesian argument that cuts leads to unemployment in a depressed economy applies regardless of whether the spending is for good or bad purposes. In other words, even if we cut $100 billion from the government Department of Waste, Fraud, and Abuse, which does nothing but write reports and throw them in the garbage, it would still slow growth and raise unemployment. The problem facing the economy right now is demand, demand, and demand. If you reduce demand, you hurt the economy.

In the longer term, when the economy does get back to something resembling full employment, it will be helpful if we can eliminate wasteful areas of government spending. Of course it would also help the economy if we can expand useful areas of government spending. But that is not particularly a Keynesian story. I assume that almost anyone would agree with these propositions even if they might draw the lines differently between wasteful and useful.

Anyhow, the reference to Keynes is a bit peculiar here. If Cowan thinks he has argued for cuts that are consistent with the Keynesian view, he is mistaken. The idea that cuts in areas of relatively strong demand like health care will have less effect on employment is at best true in only a trivial sense. Wages are not rising especially rapidly in this sector, it is not as though we have any reason to believe that there would be large numbers of additional hires to replace workers who lose their jobs due to government cutbacks, even if the impact might be marginally less than cutbacks in other sectors.

Of course Cowan also brings in the reference to investor sentiment and refers to the bond-rating agencies. This is a strange argument for a strong believer in markets. The markets are yelling at us as loudly as they can that they have no fears about the health of the U.S. government and its ability to pay its debts, hence the 2.0 percent nominal interest rates on 10-year Treasury bonds. Why would Cowan take the word of bond-rating agencies who thought subpime mortgage backed securities were Aaa over the view of financial markets?

Anyhow, it is hard to know from this column whether Cowan thinks his preferred list of cuts won’t slow growth and add to unemployment or whether the additional unemployment is a price worth paying to make the bond-rating agencies happy.

Tyler Cowan argues in his column today that we should let the sequester cuts go into effect but his argument is a bit hard to follow. He tells readers:

“One common argument against letting this process run its course is a Keynesian claim — namely, that cuts or slowdowns in government spending can throw an economy into recession by lowering total demand for goods and services. Nonetheless, spending cuts of the right kind can help an economy.”

He then goes on to point out that we can have cuts in military spending, farm subsidies and other areas that could benefit the economy.

This is where the story gets confusing. If we are looking to Keynes then the argument is straightforward, if we make cuts to the budget in a period of high unemployment like the present, then we are throwing more people out of work. These people will not be re-employed elsewhere, or if they are, they will be displacing other workers. (Btw, it’s not clear why the word “recession” appears in the paragraph. The point is simply that we would have slower growth and fewer jobs, there is no magic recession threshold in any Keynesian text I have seen.)

This Keynesian argument that cuts leads to unemployment in a depressed economy applies regardless of whether the spending is for good or bad purposes. In other words, even if we cut $100 billion from the government Department of Waste, Fraud, and Abuse, which does nothing but write reports and throw them in the garbage, it would still slow growth and raise unemployment. The problem facing the economy right now is demand, demand, and demand. If you reduce demand, you hurt the economy.

In the longer term, when the economy does get back to something resembling full employment, it will be helpful if we can eliminate wasteful areas of government spending. Of course it would also help the economy if we can expand useful areas of government spending. But that is not particularly a Keynesian story. I assume that almost anyone would agree with these propositions even if they might draw the lines differently between wasteful and useful.

Anyhow, the reference to Keynes is a bit peculiar here. If Cowan thinks he has argued for cuts that are consistent with the Keynesian view, he is mistaken. The idea that cuts in areas of relatively strong demand like health care will have less effect on employment is at best true in only a trivial sense. Wages are not rising especially rapidly in this sector, it is not as though we have any reason to believe that there would be large numbers of additional hires to replace workers who lose their jobs due to government cutbacks, even if the impact might be marginally less than cutbacks in other sectors.

Of course Cowan also brings in the reference to investor sentiment and refers to the bond-rating agencies. This is a strange argument for a strong believer in markets. The markets are yelling at us as loudly as they can that they have no fears about the health of the U.S. government and its ability to pay its debts, hence the 2.0 percent nominal interest rates on 10-year Treasury bonds. Why would Cowan take the word of bond-rating agencies who thought subpime mortgage backed securities were Aaa over the view of financial markets?

Anyhow, it is hard to know from this column whether Cowan thinks his preferred list of cuts won’t slow growth and add to unemployment or whether the additional unemployment is a price worth paying to make the bond-rating agencies happy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT is still pushing the line that, “uncertainty over fiscal policy and the fragility of the economy still seem to be holding back employers.” There is no evidence in this or prior job reports to support this contention. If employers are seeing a level of demand that would otherwise justify hiring, but are reluctant to do so because of uncertainty, they would look to fill this demand through alternative channels.

The two obvious alternatives are increasing the length of the average workweek and hiring temporary employees. The average workweek has been stable or even gotten slightly shorter in recent months. Temp hiring has been extremely weak. These facts suggest that the reason for lack of hiring is simply that employers are not seeing adequate demand, not uncertainty.

The piece also told readers:

“Economists are forecasting job growth of around 170,000 a month for the rest of 2013, comparable to job growth over the last year.”

That would probably be the view of economists who could not see an $8 trillion housing bubble. Economists with a better understanding of the economy would probably project a slower rate of job growth. The economy had been growing at just a 1.5 percent annual rate in the second half of 2012. There will be downward pressure on growth from the ending of the tax cuts and the sequester or other budget cuts. In this context it is more likely that growth will be around 120,000 a month, a pace closer to the underlying rate of growth of the labor force.

The NYT is still pushing the line that, “uncertainty over fiscal policy and the fragility of the economy still seem to be holding back employers.” There is no evidence in this or prior job reports to support this contention. If employers are seeing a level of demand that would otherwise justify hiring, but are reluctant to do so because of uncertainty, they would look to fill this demand through alternative channels.

The two obvious alternatives are increasing the length of the average workweek and hiring temporary employees. The average workweek has been stable or even gotten slightly shorter in recent months. Temp hiring has been extremely weak. These facts suggest that the reason for lack of hiring is simply that employers are not seeing adequate demand, not uncertainty.

The piece also told readers:

“Economists are forecasting job growth of around 170,000 a month for the rest of 2013, comparable to job growth over the last year.”

That would probably be the view of economists who could not see an $8 trillion housing bubble. Economists with a better understanding of the economy would probably project a slower rate of job growth. The economy had been growing at just a 1.5 percent annual rate in the second half of 2012. There will be downward pressure on growth from the ending of the tax cuts and the sequester or other budget cuts. In this context it is more likely that growth will be around 120,000 a month, a pace closer to the underlying rate of growth of the labor force.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It looks like relocation is a possibility.

It looks like relocation is a possibility.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Most people know that the deficit whiners live largely in a fact free zone, but every now and then it is worth trying to throw a few in their direction in the quest for intelligent life. The immediate motivation is Joe Scarborough’s latest tirade after having Paul Krugman as a guest on his show.

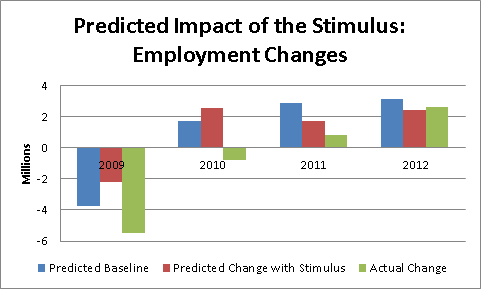

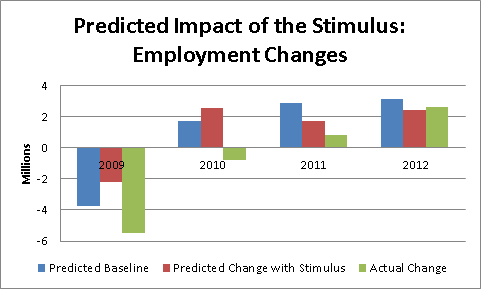

Scarborough is of the view that if stimulus was the answer the economy would have already recovered by now. In this context, we might ask what the stimulus was designed to do relative to the size of the problem.

The best evidence here is the assessment of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) from March of 2009. The reason this analysis is useful is that it is a look at what the economy was expected to do and the impact of stimulus at the time it was passed. CBO was looking at the actual stimulus as passed. It also in an independent agency with no motive to cook the books.

Here’s the picture that CBO drew compared to what actually happened.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

There are two points which should jump out at anyone. First, even as late as March of 2009 CBO hugely underestimated the severity of the downturn. The actual drop in employment from 2008 to 2009 was 5.5 million. The predicted drop was just 3.8 million. In other words, CBO underestimated the initial hit from the downturn by 1.7 million jobs, even after it was already well underway.

If anyone wants to blame the greater severity of the downturn on the stimulus they would have a hard story to tell. Most of the hit was before a dollar of the stimulus was spent. Employment in March of 2009 was 5.4 million before its year ago level.

Of course CBO was overly optimistic about the pace of the turnaround. It predicted that employment would rise by 1.7 million in 2010 even if we did nothing. Someone may have a story about how this increase would have happened had it not been for the stimulus (lower interest rates?), but it is difficult to envision what that story would look like.

The other point that this chart makes nicely is that the predicted gains from the stimulus were small relative to the size of the downturn. CBO predicted that the maximum benefit from the stimulus would be in 2010 when employment would be 2.4 million higher than without the stimulus. This needs to be repeated a few hundred thousand times the stimulus was only projected to create 2.4 million jobs.

That is not rewriting history or making it up as we go along. This is a projection from an independent agency made at the time the stimulus was passed. The economy ended up losing over 7 million jobs. At its peak impact, the stimulus was only projected to replace 2.4 million of these jobs. And after 2010 the stimulus’ impact quickly went to zero as the spending and tax cuts came to an end.

How can anyone be surprised that the stimulus did not bring the economy back to full employment? No one expected it to be large enough to reverse the impact of a slump of this magnitude.

President Obama and his team deserve lots of criticism for failing to recognize the severity of the downturn. They deserve even more blame for not acknowledging this fact, and that their stimulus was inadequate for the task at hand.

But their errors do not change the reality. The stimulus was not designed to create 7 million jobs. Why would Joe Scarborough or anyone else be surprised to see that it didn’t?

Most people know that the deficit whiners live largely in a fact free zone, but every now and then it is worth trying to throw a few in their direction in the quest for intelligent life. The immediate motivation is Joe Scarborough’s latest tirade after having Paul Krugman as a guest on his show.

Scarborough is of the view that if stimulus was the answer the economy would have already recovered by now. In this context, we might ask what the stimulus was designed to do relative to the size of the problem.

The best evidence here is the assessment of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) from March of 2009. The reason this analysis is useful is that it is a look at what the economy was expected to do and the impact of stimulus at the time it was passed. CBO was looking at the actual stimulus as passed. It also in an independent agency with no motive to cook the books.

Here’s the picture that CBO drew compared to what actually happened.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

There are two points which should jump out at anyone. First, even as late as March of 2009 CBO hugely underestimated the severity of the downturn. The actual drop in employment from 2008 to 2009 was 5.5 million. The predicted drop was just 3.8 million. In other words, CBO underestimated the initial hit from the downturn by 1.7 million jobs, even after it was already well underway.

If anyone wants to blame the greater severity of the downturn on the stimulus they would have a hard story to tell. Most of the hit was before a dollar of the stimulus was spent. Employment in March of 2009 was 5.4 million before its year ago level.

Of course CBO was overly optimistic about the pace of the turnaround. It predicted that employment would rise by 1.7 million in 2010 even if we did nothing. Someone may have a story about how this increase would have happened had it not been for the stimulus (lower interest rates?), but it is difficult to envision what that story would look like.

The other point that this chart makes nicely is that the predicted gains from the stimulus were small relative to the size of the downturn. CBO predicted that the maximum benefit from the stimulus would be in 2010 when employment would be 2.4 million higher than without the stimulus. This needs to be repeated a few hundred thousand times the stimulus was only projected to create 2.4 million jobs.

That is not rewriting history or making it up as we go along. This is a projection from an independent agency made at the time the stimulus was passed. The economy ended up losing over 7 million jobs. At its peak impact, the stimulus was only projected to replace 2.4 million of these jobs. And after 2010 the stimulus’ impact quickly went to zero as the spending and tax cuts came to an end.

How can anyone be surprised that the stimulus did not bring the economy back to full employment? No one expected it to be large enough to reverse the impact of a slump of this magnitude.

President Obama and his team deserve lots of criticism for failing to recognize the severity of the downturn. They deserve even more blame for not acknowledging this fact, and that their stimulus was inadequate for the task at hand.

But their errors do not change the reality. The stimulus was not designed to create 7 million jobs. Why would Joe Scarborough or anyone else be surprised to see that it didn’t?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks makes the case for immigration reform in his column today. Surprisingly, there is not much to dispute here. However, the story of more immigration is not quite the picture where everyone wins that he implies.

Brooks cites research by my friend Heidi Shierholz showing that wages of native born workers of all education levels increased as a result of the immigration from 1994 to 2007. The essential story here is that it models a situation where immigrants and native born workers largely fill different jobs. In this way, immigrants are not seen as competing with native born workers, but in effect providing a lower cost input into production in the same way that lower energy prices provide a lower cost input.

One can certainly point to industries and occupations where this story would seem to hold. Cab drivers in Washington, DC are almost exclusively immigrants, as are many of the people working in restaurant kitchens, as are custodians in offices and hotels. In these sectors, more immigrants would not have much impact on the wages of native born workers. (The impact of these sectors coming to be dominated by immigrants initially is another question.)

However more immigrants would be expected to have an impact on the immigrant workers in these sectors. Imagine the impact on the earnings of immigrant cab drivers in DC if we doubled the number of people driving cabs.

Sheirholz’s mid-point estimate of the effect of the 1994-2007 immigration on the wages of immigrant workers is -4.6 percent. For a worker earning $30,000 a year this is a hit of $1,380. Her high-end estimate is 6.0 percent, implying a hit of $1,800. (Interestingly, by education group she finds that college educated immigrants would be most adversely affected by more immigrants.)

Anyhow, these numbers are worth keeping in mind in designing the shape of immigration reform. It may be the case that more immigration will in general be a positive (albeit a small positive) for the wages of most native born workers, but if we want to see recent immigrants have an opportunity to quickly improve their living standards and earn wages that are closer to those of native born workers, then more immigration is not always better. (See John Schmitt’s paper on this topic.)

David Brooks makes the case for immigration reform in his column today. Surprisingly, there is not much to dispute here. However, the story of more immigration is not quite the picture where everyone wins that he implies.

Brooks cites research by my friend Heidi Shierholz showing that wages of native born workers of all education levels increased as a result of the immigration from 1994 to 2007. The essential story here is that it models a situation where immigrants and native born workers largely fill different jobs. In this way, immigrants are not seen as competing with native born workers, but in effect providing a lower cost input into production in the same way that lower energy prices provide a lower cost input.

One can certainly point to industries and occupations where this story would seem to hold. Cab drivers in Washington, DC are almost exclusively immigrants, as are many of the people working in restaurant kitchens, as are custodians in offices and hotels. In these sectors, more immigrants would not have much impact on the wages of native born workers. (The impact of these sectors coming to be dominated by immigrants initially is another question.)

However more immigrants would be expected to have an impact on the immigrant workers in these sectors. Imagine the impact on the earnings of immigrant cab drivers in DC if we doubled the number of people driving cabs.

Sheirholz’s mid-point estimate of the effect of the 1994-2007 immigration on the wages of immigrant workers is -4.6 percent. For a worker earning $30,000 a year this is a hit of $1,380. Her high-end estimate is 6.0 percent, implying a hit of $1,800. (Interestingly, by education group she finds that college educated immigrants would be most adversely affected by more immigrants.)

Anyhow, these numbers are worth keeping in mind in designing the shape of immigration reform. It may be the case that more immigration will in general be a positive (albeit a small positive) for the wages of most native born workers, but if we want to see recent immigrants have an opportunity to quickly improve their living standards and earn wages that are closer to those of native born workers, then more immigration is not always better. (See John Schmitt’s paper on this topic.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The data has not been kind to the economists and reporters who were hyping the line that uncertainties over the fiscal cliff were slowing growth last year. Strong consumption data, capped by a jump in retail sales in December seemed to dispel the idea that consumers were being cautious due to cliff concerns. Durable goods orders, led by a big jump in capital goods orders in November, suggested that businesses were acting as though the outcome of the standoff would not have a big impact on the economy.

Yesterday’s release of data on 4th quarter GDP should have been the final death knell for the fiscal cliff economic drag story. There was strong growth in both equipment and software investment by businesses and purchases of durable goods by consumers. Obviously these folks didn’t get the memo about being cautious.

But Joel Naroff, an economist with his own consulting firm, was not giving up so easily. On the PBS NewsHour last night he told viewers:

“Well, I think really what happened was that businesses were really cautious, uncertain about whether or not we’d wind up going off the fiscal cliff.

“And they made some very short-term decisions. It’s easy just to keep the warehouses essentially empty. If we don’t go off the cliff, they can refill them quickly. And so I think what happened during the end of the year was they just ran things very, very close to the vest, and now I think we will see in the first part of this year that they will have to rebuild it, and that will add to growth.”

If Naroff is looking for empty warehouses he better look at the data again. Businesses did not “keep the warehouses essentially empty” in the 4th quarter. Businesses increased non-farm inventories at a $43.8 billion annual rate in the fourth quarter, a pretty health rate. This was a drag on growth because they reportedly increased inventories at an extraordinary $88.2 billion annual rate in the third quarter. In other words, businesses went from adding inventories at a very rapid pace to adding them at a more normal pace. They were not letting their warehouses sit empty. Since GDP is measuring the change in the rate of change, a slower rate of accumulation is a drag on growth.

Call that one strike three for the fiscal cliff fearmongers.

Addendum:

Morning Edition committed the same sin: intro econ textbooks all around. Is our economists learning?

The data has not been kind to the economists and reporters who were hyping the line that uncertainties over the fiscal cliff were slowing growth last year. Strong consumption data, capped by a jump in retail sales in December seemed to dispel the idea that consumers were being cautious due to cliff concerns. Durable goods orders, led by a big jump in capital goods orders in November, suggested that businesses were acting as though the outcome of the standoff would not have a big impact on the economy.

Yesterday’s release of data on 4th quarter GDP should have been the final death knell for the fiscal cliff economic drag story. There was strong growth in both equipment and software investment by businesses and purchases of durable goods by consumers. Obviously these folks didn’t get the memo about being cautious.

But Joel Naroff, an economist with his own consulting firm, was not giving up so easily. On the PBS NewsHour last night he told viewers:

“Well, I think really what happened was that businesses were really cautious, uncertain about whether or not we’d wind up going off the fiscal cliff.

“And they made some very short-term decisions. It’s easy just to keep the warehouses essentially empty. If we don’t go off the cliff, they can refill them quickly. And so I think what happened during the end of the year was they just ran things very, very close to the vest, and now I think we will see in the first part of this year that they will have to rebuild it, and that will add to growth.”

If Naroff is looking for empty warehouses he better look at the data again. Businesses did not “keep the warehouses essentially empty” in the 4th quarter. Businesses increased non-farm inventories at a $43.8 billion annual rate in the fourth quarter, a pretty health rate. This was a drag on growth because they reportedly increased inventories at an extraordinary $88.2 billion annual rate in the third quarter. In other words, businesses went from adding inventories at a very rapid pace to adding them at a more normal pace. They were not letting their warehouses sit empty. Since GDP is measuring the change in the rate of change, a slower rate of accumulation is a drag on growth.

Call that one strike three for the fiscal cliff fearmongers.

Addendum:

Morning Edition committed the same sin: intro econ textbooks all around. Is our economists learning?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s a cheap shot derived from the information that the NYT gave us at the end of Thomas Friedman’s column: “Maureen Dowd is off today.” Nonetheless it seems an appropriate response to a piece that tells real wages for most workers are stagnating because:

“In 2004, I wrote a book, called ‘The World Is Flat,’ about how the world was getting digitally connected so more people could compete, connect and collaborate from anywhere. When I wrote that book, Facebook, Twitter, cloud computing, LinkedIn, 4G wireless, ultra-high-speed bandwidth, big data, Skype, system-on-a-chip (SOC) circuits, iPhones, iPods, iPads and cellphone apps didn’t exist, or were in their infancy.

Today, not only do all these things exist, but, in combination, they’ve taken us from connected to hyperconnected.”

So Facebook and Twitter are the cause of wage inequality? I knew there was some reason Mark Zuckerberg rubbed me the wrong way.

Friedman also tells us:

“we have record productivity, wealth and innovation, yet median incomes are falling, inequality is rising and high unemployment remains persistent.”

Well the first part of this statement is almost always true. Except for short periods at the start of recessions, productivity always rises, implying greater wealth and presumably record innovation (not sure how that is measured).

Anyhow, it is not clear why Friedman finds anything surprising about this coinciding with high unemployment. Those of us who follow the economy would point to the fact that nothing has replaced the $1.2 trillion in annual construction and consumption demand that we lost when the housing bubble collapsed. And when we get more demand employment would grow, labor markets would tighten and we would see most workers in a position to get higher wages. There is no mystery here to folks who know basic economics and a bit of arithmetic.

Friedman wants people to have:

“more P.Q. (passion quotient) and C.Q. (curiosity quotient) to leverage all the new digital tools to not just find a job, but to invent one or reinvent one, and to not just learn but to relearn for a lifetime.”

Yeah, it would be great if people had more passion, curiousity and learned more, but it’s not clear that this would affect wages much for the 14.9 million people working in retail, the 10 million people employed in restauarants and the 1.8 million employed in hotels. In other words, even in Friedman’s hyperconnected world, a very high percentage of jobs still do not offer many opportunities for passion, curiousity, and learning.

The reason that these people are not sharing in the benefits of productivity growth, as they did in the period from 1945 to 1973 is that the folks controlling economic policy lack passion, curiousity and an interest in learning. They think it’s just fine that we waste $1 trillion a year due to an economy that is below full employment and that 15 million people are unemployed and underemployed.

Anyhow, maybe we can get the NYT to fix that line about Maureen Dowd.

That’s a cheap shot derived from the information that the NYT gave us at the end of Thomas Friedman’s column: “Maureen Dowd is off today.” Nonetheless it seems an appropriate response to a piece that tells real wages for most workers are stagnating because:

“In 2004, I wrote a book, called ‘The World Is Flat,’ about how the world was getting digitally connected so more people could compete, connect and collaborate from anywhere. When I wrote that book, Facebook, Twitter, cloud computing, LinkedIn, 4G wireless, ultra-high-speed bandwidth, big data, Skype, system-on-a-chip (SOC) circuits, iPhones, iPods, iPads and cellphone apps didn’t exist, or were in their infancy.

Today, not only do all these things exist, but, in combination, they’ve taken us from connected to hyperconnected.”

So Facebook and Twitter are the cause of wage inequality? I knew there was some reason Mark Zuckerberg rubbed me the wrong way.

Friedman also tells us:

“we have record productivity, wealth and innovation, yet median incomes are falling, inequality is rising and high unemployment remains persistent.”

Well the first part of this statement is almost always true. Except for short periods at the start of recessions, productivity always rises, implying greater wealth and presumably record innovation (not sure how that is measured).

Anyhow, it is not clear why Friedman finds anything surprising about this coinciding with high unemployment. Those of us who follow the economy would point to the fact that nothing has replaced the $1.2 trillion in annual construction and consumption demand that we lost when the housing bubble collapsed. And when we get more demand employment would grow, labor markets would tighten and we would see most workers in a position to get higher wages. There is no mystery here to folks who know basic economics and a bit of arithmetic.

Friedman wants people to have:

“more P.Q. (passion quotient) and C.Q. (curiosity quotient) to leverage all the new digital tools to not just find a job, but to invent one or reinvent one, and to not just learn but to relearn for a lifetime.”

Yeah, it would be great if people had more passion, curiousity and learned more, but it’s not clear that this would affect wages much for the 14.9 million people working in retail, the 10 million people employed in restauarants and the 1.8 million employed in hotels. In other words, even in Friedman’s hyperconnected world, a very high percentage of jobs still do not offer many opportunities for passion, curiousity, and learning.

The reason that these people are not sharing in the benefits of productivity growth, as they did in the period from 1945 to 1973 is that the folks controlling economic policy lack passion, curiousity and an interest in learning. They think it’s just fine that we waste $1 trillion a year due to an economy that is below full employment and that 15 million people are unemployed and underemployed.

Anyhow, maybe we can get the NYT to fix that line about Maureen Dowd.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión