Floyd Norris is worried about a sharp drop in consumer confidence. He shouldn’t be.

The cause of the drop is a fall in consumer expectations about the future. Expectations jump around because most people aren’t in the business of sitting down and thinking about where the economy will be in 6 months. For the most part, people answer this question based on what they hear in the news. Since news reporting on the economy is very fickle, people’s views about the future are very fickle.

Fortunately, expectations have very little impact on people’s consumption decisions. Their consumption is far more stable, indicating that people rely on their current economic situation — wages, job security, housing equity — in making their consumption decisions and they largely ignore the folks seen and heard pontificating in the media.

Floyd Norris is worried about a sharp drop in consumer confidence. He shouldn’t be.

The cause of the drop is a fall in consumer expectations about the future. Expectations jump around because most people aren’t in the business of sitting down and thinking about where the economy will be in 6 months. For the most part, people answer this question based on what they hear in the news. Since news reporting on the economy is very fickle, people’s views about the future are very fickle.

Fortunately, expectations have very little impact on people’s consumption decisions. Their consumption is far more stable, indicating that people rely on their current economic situation — wages, job security, housing equity — in making their consumption decisions and they largely ignore the folks seen and heard pontificating in the media.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is yet another case where the free market fundamentalists are using big government to fatten their profits. Associated Press has a nice piece on how several states are paying their unemployment insurance benefits through electronic cards issued by banks rather than checks or direct deposits. The banks place various fees on these cards that people with bank accounts, who are most of the unemployed, would not otherwise see. Needless to say, these banks are very happy with big government and would be very much opposed to an efficient more market based mechanism for paying benefits.

This is yet another case where the free market fundamentalists are using big government to fatten their profits. Associated Press has a nice piece on how several states are paying their unemployment insurance benefits through electronic cards issued by banks rather than checks or direct deposits. The banks place various fees on these cards that people with bank accounts, who are most of the unemployed, would not otherwise see. Needless to say, these banks are very happy with big government and would be very much opposed to an efficient more market based mechanism for paying benefits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When the Post ran a piece on the lessons that Harley-Davidson teaches us about the economy readers naturally assumed that it would mention it as an example of successful protectionism. In 1982, in the middle of a steep recession, President Reagan imposed tariffs on imported motorcycles. This gave Harley-Davidson the breathing room it needed to survive the recession and modernize its operations. It continues to be a healthy profitable company.

Anyhow, this history didn’t make the Post’s list, but the other items are nonetheless interesting.

When the Post ran a piece on the lessons that Harley-Davidson teaches us about the economy readers naturally assumed that it would mention it as an example of successful protectionism. In 1982, in the middle of a steep recession, President Reagan imposed tariffs on imported motorcycles. This gave Harley-Davidson the breathing room it needed to survive the recession and modernize its operations. It continues to be a healthy profitable company.

Anyhow, this history didn’t make the Post’s list, but the other items are nonetheless interesting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what listeners to a segment this morning on households’ lack of adequate savings probably concluded. The piece noted that many households lack the savings needed to support themselves through a period of unemployment or illness. It then talked about various efforts to promote savings.

While it would be beneficial for most people to save more (although it would hurt the economy in the short-run), a major problem is the large fees charged by financial institutions. Fees can eat up as much as one-third of the money in 401(k)-type accounts. It would have been worth at least mentioning the problem of high bank fees as an issue in this discussion.

That’s what listeners to a segment this morning on households’ lack of adequate savings probably concluded. The piece noted that many households lack the savings needed to support themselves through a period of unemployment or illness. It then talked about various efforts to promote savings.

While it would be beneficial for most people to save more (although it would hurt the economy in the short-run), a major problem is the large fees charged by financial institutions. Fees can eat up as much as one-third of the money in 401(k)-type accounts. It would have been worth at least mentioning the problem of high bank fees as an issue in this discussion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Can we get a heaping helping of ridicule for all the reporters and their favorite economic experts who told us that uncertainty over the fiscal cliff was a drag on the economy in the second half of 2012? The data just refuse to comply with this assessment.

Yesterday the Commerce Department reported a big jump in durable goods orders for the month of December. This was right when we stood at the precipice waiting to see if we would slide over the cliff. Orders jumped 4.6 percent for the month. Non-defense capital good orders (excluding aircraft) were up also, although by just 0.2 percent. However, this followed a 3.0 percent rise in November. If uncertainty was supposed to be discouraging investment, the folks making the orders apparently didn’t get the memo.

This also seems to have been the case with employers, since employment increased by 155,000 in December, the same as its average over the last year. Retail sales also rose by a strong 0.5 percent, indicating that consumers were also too dumb to recognize the uncertainty caused by the fiscal cliff.

In short, it seems that the folks who make the relevant economic decisions did not agree with the economic experts. They ignored the uncertainty surrounding the fiscal cliff and just acted as though the boys and girls in Washington would get things worked out without seriously disrupting the economy. And they were right.

Addendum:

Big congrats to Neil Irwin at the Post for nailing this one exactly right today and fessing up to his past mistakes in covering the cliff.

Can we get a heaping helping of ridicule for all the reporters and their favorite economic experts who told us that uncertainty over the fiscal cliff was a drag on the economy in the second half of 2012? The data just refuse to comply with this assessment.

Yesterday the Commerce Department reported a big jump in durable goods orders for the month of December. This was right when we stood at the precipice waiting to see if we would slide over the cliff. Orders jumped 4.6 percent for the month. Non-defense capital good orders (excluding aircraft) were up also, although by just 0.2 percent. However, this followed a 3.0 percent rise in November. If uncertainty was supposed to be discouraging investment, the folks making the orders apparently didn’t get the memo.

This also seems to have been the case with employers, since employment increased by 155,000 in December, the same as its average over the last year. Retail sales also rose by a strong 0.5 percent, indicating that consumers were also too dumb to recognize the uncertainty caused by the fiscal cliff.

In short, it seems that the folks who make the relevant economic decisions did not agree with the economic experts. They ignored the uncertainty surrounding the fiscal cliff and just acted as though the boys and girls in Washington would get things worked out without seriously disrupting the economy. And they were right.

Addendum:

Big congrats to Neil Irwin at the Post for nailing this one exactly right today and fessing up to his past mistakes in covering the cliff.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT tells us that biotech firms want the government to prohibit pharmacists from giving patients generic substitutes for biological drugs. This is a great story for a couple of reasons.

First it is a great example of the sort of abuses that economic theory predicts would result from having the government grant patent monopolies. When companies call sell drugs for prices that are a hundred or even a thousand times their cost of production, we should expect that they will lie, cheat, and steal to expand their market. And the drug companies largely act exactly as economic theory, if not economists, predicts.

The other reason this is a great story is that it shows the complete indifference to free market principles held by big business. Are the folks who want to arrest pharmacists for substituting generics “market fundamentalists?”

Note that the sums of money involved in the industry swamp the chump change that many liberals fight over. The article cites data showing drug industry sales at $320 billion a year. They would be around one-tenth this amount without patent and other protections provided by the government, a difference of $290 billion. By comparison, the entire food stamp program cost $87 billion in 2012, less than one-third this amount. Federal spending on TANF is around $17 billion, less than one-tenth of this amount.

This is a great example of how the rich rig rules to get all the money. Then they let the loser liberals run around saying that we need the government to help the poor.

Addendum: Zev Arnold pointed out in his comment that I orginally had the number of beneficiaries (47 million) rather than the amount of spending for Food Stamps.

The NYT tells us that biotech firms want the government to prohibit pharmacists from giving patients generic substitutes for biological drugs. This is a great story for a couple of reasons.

First it is a great example of the sort of abuses that economic theory predicts would result from having the government grant patent monopolies. When companies call sell drugs for prices that are a hundred or even a thousand times their cost of production, we should expect that they will lie, cheat, and steal to expand their market. And the drug companies largely act exactly as economic theory, if not economists, predicts.

The other reason this is a great story is that it shows the complete indifference to free market principles held by big business. Are the folks who want to arrest pharmacists for substituting generics “market fundamentalists?”

Note that the sums of money involved in the industry swamp the chump change that many liberals fight over. The article cites data showing drug industry sales at $320 billion a year. They would be around one-tenth this amount without patent and other protections provided by the government, a difference of $290 billion. By comparison, the entire food stamp program cost $87 billion in 2012, less than one-third this amount. Federal spending on TANF is around $17 billion, less than one-tenth of this amount.

This is a great example of how the rich rig rules to get all the money. Then they let the loser liberals run around saying that we need the government to help the poor.

Addendum: Zev Arnold pointed out in his comment that I orginally had the number of beneficiaries (47 million) rather than the amount of spending for Food Stamps.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It probably would have been useful to remind readers that Representative Paul Ryan’s claim that country is facing a fiscal crisis is sharply at odds with the views of market participants in a NYT article reporting on his latest interview. The article quotes Ryan:

“I don’t think that the president thinks that we actually have a fiscal crisis, … He’s been reportedly saying to our leaders that we don’t have a spending problem, we have a health care problem. That just leads me to conclude that he actually thinks we just need more government-run health care.”

Of course the fact that investors are willing to lend the U.S. government trillions of dollars for long periods of time for interest rates of less than 2.0 percent indicates that the markets do not believe the United States has a fiscal crisis. Also, it is a fact that if the United States had per person health care costs that were at all comparable to those in other wealthy countries that it would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficits.

It would have been worth reminding readers that Mr. Ryan has no evidence to support his assertions that the United States somehow has a fiscal crisis or that fixing our health care system would not address its projected long-term deficit problem. Readers might be mistakenly led to believe that Ryan’s position has a basis in reality.

It probably would have been useful to remind readers that Representative Paul Ryan’s claim that country is facing a fiscal crisis is sharply at odds with the views of market participants in a NYT article reporting on his latest interview. The article quotes Ryan:

“I don’t think that the president thinks that we actually have a fiscal crisis, … He’s been reportedly saying to our leaders that we don’t have a spending problem, we have a health care problem. That just leads me to conclude that he actually thinks we just need more government-run health care.”

Of course the fact that investors are willing to lend the U.S. government trillions of dollars for long periods of time for interest rates of less than 2.0 percent indicates that the markets do not believe the United States has a fiscal crisis. Also, it is a fact that if the United States had per person health care costs that were at all comparable to those in other wealthy countries that it would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficits.

It would have been worth reminding readers that Mr. Ryan has no evidence to support his assertions that the United States somehow has a fiscal crisis or that fixing our health care system would not address its projected long-term deficit problem. Readers might be mistakenly led to believe that Ryan’s position has a basis in reality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, that is not exactly what he said, but if Chrystia Freeland’s account of Summers’ comments at Davos is to be believed Summers is badly misinformed about the state of the U.S. economy in 1993, when he was one of the top advisers in the Clinton administration. According to Freeland Summers said:

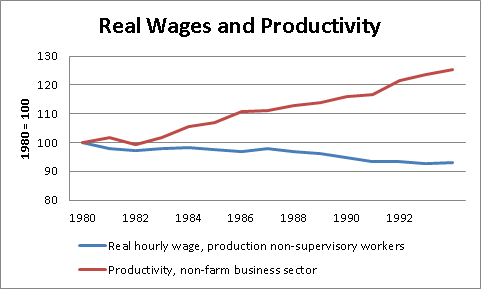

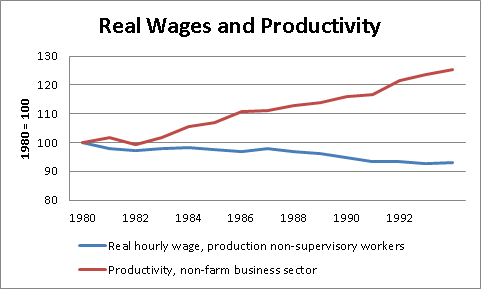

“In 1993, here’s what the situation was: Capital costs were really high, the trade deficit was really big, and if you looked at a graph of average wages and the productivity of American workers, those two graphs lay on top of each other. So, bringing down the deficit, reducing capital costs, raising investment, spurring productivity growth, was the right and natural central strategy for spurring growth. That was what Bob Rubin advised Bill Clinton, that was the advice Bill Clinton followed, and they were right.”

This is not what the data say. Here’s the story on real wages and productivity.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There are some measurement issues that would reduce the gap somewhat, but anyone who could see these two as laying “on top of each other” needs some new glasses. The sharp divergence between productivity and wages began in the 1980s. It would be really scary if Larry Summers, Robert Rubin and the rest did not know this in 1993.

The other parts of Summers’ story are also wrong. The trade deficit was less than 1.0 percent of GDP in 1993. By comparison it was almost 4.0 percent of GDP when Clinton left office in 2000. The interest rate on ten-year Treasury bonds was 6.6 percent in January of 1993. Coupled with an inflation rate of around 3.0-3.5 percent, this gave a real interest rate in the neighborhood of 3.1-3.6 percent. This is perhaps a bit higher than desirable, but actually not much different than what we saw through most of the Clinton years.

In short, Summers is describing a history that does not exist. He either has a very poor memory or is just making things up.

Okay, that is not exactly what he said, but if Chrystia Freeland’s account of Summers’ comments at Davos is to be believed Summers is badly misinformed about the state of the U.S. economy in 1993, when he was one of the top advisers in the Clinton administration. According to Freeland Summers said:

“In 1993, here’s what the situation was: Capital costs were really high, the trade deficit was really big, and if you looked at a graph of average wages and the productivity of American workers, those two graphs lay on top of each other. So, bringing down the deficit, reducing capital costs, raising investment, spurring productivity growth, was the right and natural central strategy for spurring growth. That was what Bob Rubin advised Bill Clinton, that was the advice Bill Clinton followed, and they were right.”

This is not what the data say. Here’s the story on real wages and productivity.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There are some measurement issues that would reduce the gap somewhat, but anyone who could see these two as laying “on top of each other” needs some new glasses. The sharp divergence between productivity and wages began in the 1980s. It would be really scary if Larry Summers, Robert Rubin and the rest did not know this in 1993.

The other parts of Summers’ story are also wrong. The trade deficit was less than 1.0 percent of GDP in 1993. By comparison it was almost 4.0 percent of GDP when Clinton left office in 2000. The interest rate on ten-year Treasury bonds was 6.6 percent in January of 1993. Coupled with an inflation rate of around 3.0-3.5 percent, this gave a real interest rate in the neighborhood of 3.1-3.6 percent. This is perhaps a bit higher than desirable, but actually not much different than what we saw through most of the Clinton years.

In short, Summers is describing a history that does not exist. He either has a very poor memory or is just making things up.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT told us that Bank of America made $5.7 billion from “trading” last year. It then added:

“For the sake of clarity and consistency, it makes sense to relabel this type of revenue “market-making.” That’s because it mainly represents the gain Bank of America makes when it buys securities and sells them on to clients at a higher price.”

Really? The NYT knows that it just turned out that the price of assets rose by $5.7 billion between the time when Bank of America acquired them and when they passed them on to their clients? That sounds like some pretty good luck for BoA. After all, we would expect that roughly half of the time when BoA buys an asset for a client and when it actually passes the asset on to the client the price would fall. If the net in this story came to a plus $5.7 billion that would seem like a remarkable streak of good luck for BoA.

Let’s try an alternative hypothesis. Let’s imagine that BoA was trading on its account, deliberately trying to find assets that would rise in price. If BoA has well-informed people doing its buying and selling, then it might not be too hard to believe that it could clear $5.7 billion on this sort of trading.

Of course trading on its own account would likely violate the law. This is exactly what the Volcker Rule intended to prevent. So it would be very helpful if people thought that BoA made this $5.7 billion from market-making.

Addendum:

In response to a question below, let me clarify the meaning of “trading on its own account.” A market maker must be prepared to take positions on assets for at least short periods of time in order to service its clients. This means, for example, if a client wants to sell shares of stock or some other asset, then the market maker has to be prepared to buy and hold the asset until another buyer comes along. In principle, they will pay somewhat below the market price at the time to cover the risk that the price will fall before they can offload the stock and to cover the cost of their services.

By contrast, if a bank is trading on its account it is deliberately taking a directional bet on the asset. It is not always easy to distinguish between a trade where a bank is simply acting as a market maker and a trade where it is consciously making a bet that an asset will rise or fall in price. When the Volcker Rule is firmly in place the latter will not be legal for banks like Bank of America that have government guaranteed deposits.

It is entirely possible that BoA’s $5.7 billion in trading profits were entirely due to market making activities, however that does seem unlikely since it is a substantial amount of profit on what would be a relatively small portion of the bank’s revenue. In any case, rather than assuring readers that BoA is acting in a manner that would be in full compliance with the Volcker Rule, it would seem more appropriate to simply report its claims and let the readers make this assessment, unless the NYT has actually investigated the bank’s trading practices and feels comfortable making this assurance to readers.

The NYT told us that Bank of America made $5.7 billion from “trading” last year. It then added:

“For the sake of clarity and consistency, it makes sense to relabel this type of revenue “market-making.” That’s because it mainly represents the gain Bank of America makes when it buys securities and sells them on to clients at a higher price.”

Really? The NYT knows that it just turned out that the price of assets rose by $5.7 billion between the time when Bank of America acquired them and when they passed them on to their clients? That sounds like some pretty good luck for BoA. After all, we would expect that roughly half of the time when BoA buys an asset for a client and when it actually passes the asset on to the client the price would fall. If the net in this story came to a plus $5.7 billion that would seem like a remarkable streak of good luck for BoA.

Let’s try an alternative hypothesis. Let’s imagine that BoA was trading on its account, deliberately trying to find assets that would rise in price. If BoA has well-informed people doing its buying and selling, then it might not be too hard to believe that it could clear $5.7 billion on this sort of trading.

Of course trading on its own account would likely violate the law. This is exactly what the Volcker Rule intended to prevent. So it would be very helpful if people thought that BoA made this $5.7 billion from market-making.

Addendum:

In response to a question below, let me clarify the meaning of “trading on its own account.” A market maker must be prepared to take positions on assets for at least short periods of time in order to service its clients. This means, for example, if a client wants to sell shares of stock or some other asset, then the market maker has to be prepared to buy and hold the asset until another buyer comes along. In principle, they will pay somewhat below the market price at the time to cover the risk that the price will fall before they can offload the stock and to cover the cost of their services.

By contrast, if a bank is trading on its account it is deliberately taking a directional bet on the asset. It is not always easy to distinguish between a trade where a bank is simply acting as a market maker and a trade where it is consciously making a bet that an asset will rise or fall in price. When the Volcker Rule is firmly in place the latter will not be legal for banks like Bank of America that have government guaranteed deposits.

It is entirely possible that BoA’s $5.7 billion in trading profits were entirely due to market making activities, however that does seem unlikely since it is a substantial amount of profit on what would be a relatively small portion of the bank’s revenue. In any case, rather than assuring readers that BoA is acting in a manner that would be in full compliance with the Volcker Rule, it would seem more appropriate to simply report its claims and let the readers make this assessment, unless the NYT has actually investigated the bank’s trading practices and feels comfortable making this assurance to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión