The Fed reported a sharp jump in manufacturing output in December, demonstrating that factory owners were too dumb to realize that they were supposed to be cutting back production because of worries over the fiscal cliff. Earlier in the week the Commerce Department reported that consumers were also too stupid to realize that they were supposed to be cutting back their purchases over such concerns. Clearly the economy has serious problems when manufacturers and consumers refuse to act in the way that leading economists say they should be acting.

The Fed reported a sharp jump in manufacturing output in December, demonstrating that factory owners were too dumb to realize that they were supposed to be cutting back production because of worries over the fiscal cliff. Earlier in the week the Commerce Department reported that consumers were also too stupid to realize that they were supposed to be cutting back their purchases over such concerns. Clearly the economy has serious problems when manufacturers and consumers refuse to act in the way that leading economists say they should be acting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

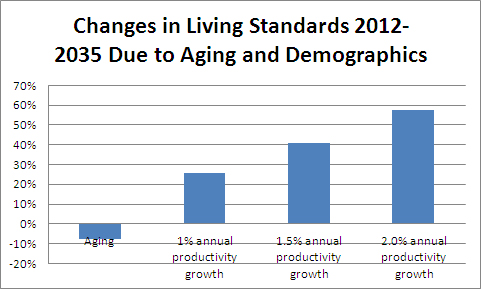

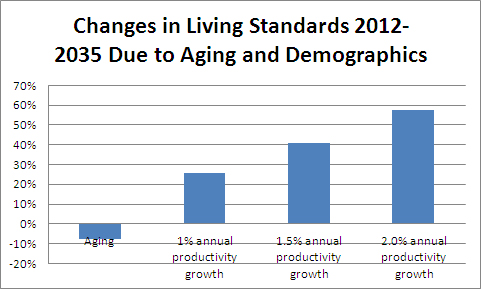

Thomas Edsall devotes his blog post this week to Walter Russell Mead and a number of others who tell him that demographic change is going to wipe out the welfare state. The problem is that the projections don’t support this story. The impact of projected future demographic change on the budget is actually fairly limited.

In 2001 Social Security cost 4.1 percent of GDP (Table F-5). It current costs 5.1 percent of GDP (Table 3-1). Over the next two decades the cost is projected to increase by roughly the same amount as it did in the last dozen years. That doesn’t seem like an insurmountable burden. In fact, if the projected shortfall in Social Security funding for the rest of the century were filled entirely through an increase in the payroll tax, the necessary tax increase would amount to 7 percent of projected wage growth over the next two decades and just 4.0 percent of the wage growth over the next 40 years. (This assumes that workers get their share of productivity gains, which is a key issue that has little to do with demographics.) The tax burden would be lessened insofar as part of the projected shortfall was filled by making the tax more progressive (e.g. raising the cap) or cutting benefits.

The rise in Medicare costs is projected to be larger, but this is due to the projected rise in per person health care costs, not demographics. (People don’t age any more rapidly in the Medicare program than in Social Security.) This emphasizes the need to control health care costs, which are already more than twice as much per person in the United States as the average for other wealthy countries. This ratio is projected to grow to 3 or 4 to 1 in the decades ahead.

It is wrong to refer to the projected explosion of health care costs as a demographic issue. It stems from an inability to confront the powerful lobbies (drug companies, medical equipment companies and doctors) who profit from the waste in the U.S. health care system. The actual impact of demographic change is swamped by productivity growth. It is probably also worth noting in the context of this piece that the ratio of interest on the government debt to GDP is near a post-World War II low.

Source: Social Security Trustees Reports and Author’s Calculations.

This blogpost also refers to the projected shortfall in state and local pension funds, telling readers:

“Dozens of city and state public employee pension plans are on the verge of bankruptcy – or are actually bankrupt – from Rhode Island to California; in 2010, a survey of 126 state and local plans showed assets of $2.7 trillion and liabilities of $3.5 trillion, an $800 billion shortfall.”

This $800 billion shortfall is less than 0.4 percent of projected GDP over the next 30 years, the time horizon in which most of these benefits are projected to be paid. That is less than one fourth of the increase in military spending associated with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan or the additional money projected to flow to the pharmaceutical industry as a result of government granted patent monopolies.

Thomas Edsall devotes his blog post this week to Walter Russell Mead and a number of others who tell him that demographic change is going to wipe out the welfare state. The problem is that the projections don’t support this story. The impact of projected future demographic change on the budget is actually fairly limited.

In 2001 Social Security cost 4.1 percent of GDP (Table F-5). It current costs 5.1 percent of GDP (Table 3-1). Over the next two decades the cost is projected to increase by roughly the same amount as it did in the last dozen years. That doesn’t seem like an insurmountable burden. In fact, if the projected shortfall in Social Security funding for the rest of the century were filled entirely through an increase in the payroll tax, the necessary tax increase would amount to 7 percent of projected wage growth over the next two decades and just 4.0 percent of the wage growth over the next 40 years. (This assumes that workers get their share of productivity gains, which is a key issue that has little to do with demographics.) The tax burden would be lessened insofar as part of the projected shortfall was filled by making the tax more progressive (e.g. raising the cap) or cutting benefits.

The rise in Medicare costs is projected to be larger, but this is due to the projected rise in per person health care costs, not demographics. (People don’t age any more rapidly in the Medicare program than in Social Security.) This emphasizes the need to control health care costs, which are already more than twice as much per person in the United States as the average for other wealthy countries. This ratio is projected to grow to 3 or 4 to 1 in the decades ahead.

It is wrong to refer to the projected explosion of health care costs as a demographic issue. It stems from an inability to confront the powerful lobbies (drug companies, medical equipment companies and doctors) who profit from the waste in the U.S. health care system. The actual impact of demographic change is swamped by productivity growth. It is probably also worth noting in the context of this piece that the ratio of interest on the government debt to GDP is near a post-World War II low.

Source: Social Security Trustees Reports and Author’s Calculations.

This blogpost also refers to the projected shortfall in state and local pension funds, telling readers:

“Dozens of city and state public employee pension plans are on the verge of bankruptcy – or are actually bankrupt – from Rhode Island to California; in 2010, a survey of 126 state and local plans showed assets of $2.7 trillion and liabilities of $3.5 trillion, an $800 billion shortfall.”

This $800 billion shortfall is less than 0.4 percent of projected GDP over the next 30 years, the time horizon in which most of these benefits are projected to be paid. That is less than one fourth of the increase in military spending associated with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan or the additional money projected to flow to the pharmaceutical industry as a result of government granted patent monopolies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article that reported on the surge in college education in China told readers, “Japan’s experience shows that having more graduates does not guarantee entrepreneurial creativity,” referring to the growth slowdown of the last two decades. While it is possible that a lack of innovation is a factor in this slowdown, it is far from obvious that this is the case. Japan does still have a large trade surplus with the United States, suggesting that U.S. consumers like the things produced in Japan more than Japanese consumers like the things produced in the United States.

It is also very plausible that Japan’s weak growth is attributable to inept economic policy. Deficit scolds of the sort that dominate U.S. policy debate have restrained the government from running larger deficits even though its ratio of interest payments to GDP is less than 1.0 percent and it remains plagued by deflation. It is rather presumptuous to assert that a failure of innovation is a major problem in this context when no evidence is presented to support this contention.

A NYT article that reported on the surge in college education in China told readers, “Japan’s experience shows that having more graduates does not guarantee entrepreneurial creativity,” referring to the growth slowdown of the last two decades. While it is possible that a lack of innovation is a factor in this slowdown, it is far from obvious that this is the case. Japan does still have a large trade surplus with the United States, suggesting that U.S. consumers like the things produced in Japan more than Japanese consumers like the things produced in the United States.

It is also very plausible that Japan’s weak growth is attributable to inept economic policy. Deficit scolds of the sort that dominate U.S. policy debate have restrained the government from running larger deficits even though its ratio of interest payments to GDP is less than 1.0 percent and it remains plagued by deflation. It is rather presumptuous to assert that a failure of innovation is a major problem in this context when no evidence is presented to support this contention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what readers of an article on the state of the French economy must have concluded. The piece paints a very dire picture of France’s economy, comparing it unfavorable with Spain, which is praised for instituting severe austerity measures.

While Spain’s austerity measures have succeeded in raising its unemployment rate to more than 25 percent, the highest in Europe, they have not brought about growth. Its economy shrank this year and is projected by the IMF to shrink by another 1.3 percent next year. France’s economy is projected to grow by 0.4 percent. In fact, the IMF projects that France’s growth will modestly outpace Spain’s through the remainder of its forecast period (2014-2017) as well.

In short, given the evidence on their relative economic performances it is unlikely that anyone in France would envy Spain, unless of course they viewed unemployment as an end in itself.

That is what readers of an article on the state of the French economy must have concluded. The piece paints a very dire picture of France’s economy, comparing it unfavorable with Spain, which is praised for instituting severe austerity measures.

While Spain’s austerity measures have succeeded in raising its unemployment rate to more than 25 percent, the highest in Europe, they have not brought about growth. Its economy shrank this year and is projected by the IMF to shrink by another 1.3 percent next year. France’s economy is projected to grow by 0.4 percent. In fact, the IMF projects that France’s growth will modestly outpace Spain’s through the remainder of its forecast period (2014-2017) as well.

In short, given the evidence on their relative economic performances it is unlikely that anyone in France would envy Spain, unless of course they viewed unemployment as an end in itself.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a piece telling readers that business leaders do not have the same influence with Republicans in Congress that they had in the past, noting in particular their differences on using the debt ceiling as a bargaining chip in budget negotiations. It is important to note that the fact that politicians are willing to say that they would be prepared to push the government to a default doesn’t mean that they actually would push the government to default.

It is relatively costless for a politician to publicly say that he/she feels so strongly about excessive spending that she would let the government default when the country is at least a month away from any deadline. Such appeals are popular with many voters. However this does not mean that these politicians would vote against raising the debt ceiling when the government actually faced default. The history has been that the Republican leadership has been able to get the necessary support on votes that were deemed important for business, such as the TARP. This article presents no reason to believe that situation has changed.

The NYT ran a piece telling readers that business leaders do not have the same influence with Republicans in Congress that they had in the past, noting in particular their differences on using the debt ceiling as a bargaining chip in budget negotiations. It is important to note that the fact that politicians are willing to say that they would be prepared to push the government to a default doesn’t mean that they actually would push the government to default.

It is relatively costless for a politician to publicly say that he/she feels so strongly about excessive spending that she would let the government default when the country is at least a month away from any deadline. Such appeals are popular with many voters. However this does not mean that these politicians would vote against raising the debt ceiling when the government actually faced default. The history has been that the Republican leadership has been able to get the necessary support on votes that were deemed important for business, such as the TARP. This article presents no reason to believe that situation has changed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eduardo Porter had a nice piece in the NYT making the point that privatized services will often be less efficient than publicly provided services. Porter notes research that argues that when the service in question is not well-defined and easily measured it is likely to better provided directly by the public sector. This would be the case with education, health care and other major services that are largely provided by the government.

Eduardo Porter had a nice piece in the NYT making the point that privatized services will often be less efficient than publicly provided services. Porter notes research that argues that when the service in question is not well-defined and easily measured it is likely to better provided directly by the public sector. This would be the case with education, health care and other major services that are largely provided by the government.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The answer is $11.5 million, at least if you work at J.P. Morgan. That is what Jamie Dimon took home last year according to the WSJ. This was half of his prior year’s take, apparently this is the punishment for allowing his London Whale crew to engage in risky trading that cost the bank $6.2 billion.

The answer is $11.5 million, at least if you work at J.P. Morgan. That is what Jamie Dimon took home last year according to the WSJ. This was half of his prior year’s take, apparently this is the punishment for allowing his London Whale crew to engage in risky trading that cost the bank $6.2 billion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

For some reason it was hard to find news about December retail sales in the papers. The Census Department reported they were up a healthy 0.5 percent. Remember all those stories from worried economists that told us how the fiscal cliff was already taking a toll. They told us about plunging confidence levels and consumers who were putting off purchases because of uncertainty about the resolution of the standoff.

Yes, some of us did ridicule the cliff mongers at the time. Consumers are used to the boys and girls in Washington getting silly. They will adjust their spending when they actually feel the impact in their paycheck.

Anyhow, some of us were right. Get out a heaping helping of ridicule for everyone else.

For some reason it was hard to find news about December retail sales in the papers. The Census Department reported they were up a healthy 0.5 percent. Remember all those stories from worried economists that told us how the fiscal cliff was already taking a toll. They told us about plunging confidence levels and consumers who were putting off purchases because of uncertainty about the resolution of the standoff.

Yes, some of us did ridicule the cliff mongers at the time. Consumers are used to the boys and girls in Washington getting silly. They will adjust their spending when they actually feel the impact in their paycheck.

Anyhow, some of us were right. Get out a heaping helping of ridicule for everyone else.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Those of you who didn’t know the cause of Japan’s debt problems, or perhaps that it even had debt problems, will be happy to know that the NYT has the answers for you. In an article on the new prime minister Shinzo Abe’s plans for economic stimulus and expansionary monetary policy it told readers:

“At the root of Japan’s debt problems was a similar attempt in the 1990s by Mr. Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party to stimulate economic growth through government spending on extensive public works projects across the country.”

That’s good to know. Those of us who look at data on Japan’s debt might have thought that the main reason for the growth of the debt in Japan was the collapse of the stock and housing bubbles in 1990-1991. The economic downturn and deflation caused by this collapse had already raised the debt to GDP ratio by 10 percentage points by 1993 (@$1.6 trillion in the United States), a point at which deficits were still minimal.

We also might not have known that Japan has debt problems. The interest burden of its debt is now roughly 1.0 percent of GDP, lower than the interest burden in United States at any point in the post-World War II era and less than one-third of the peak burden hit in the early 90s. The interest rate on 10-year Japanese government bonds has been hovering near 1.0 percent. This isn’t the sort of interest rate that is ordinarily associated with a debt problem.

That’s why readers are thankful for the information the NYT gave us in this article. If they had just relied on the data, they wouldn’t know these things about Japan’s economic situation.

Those of you who didn’t know the cause of Japan’s debt problems, or perhaps that it even had debt problems, will be happy to know that the NYT has the answers for you. In an article on the new prime minister Shinzo Abe’s plans for economic stimulus and expansionary monetary policy it told readers:

“At the root of Japan’s debt problems was a similar attempt in the 1990s by Mr. Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party to stimulate economic growth through government spending on extensive public works projects across the country.”

That’s good to know. Those of us who look at data on Japan’s debt might have thought that the main reason for the growth of the debt in Japan was the collapse of the stock and housing bubbles in 1990-1991. The economic downturn and deflation caused by this collapse had already raised the debt to GDP ratio by 10 percentage points by 1993 (@$1.6 trillion in the United States), a point at which deficits were still minimal.

We also might not have known that Japan has debt problems. The interest burden of its debt is now roughly 1.0 percent of GDP, lower than the interest burden in United States at any point in the post-World War II era and less than one-third of the peak burden hit in the early 90s. The interest rate on 10-year Japanese government bonds has been hovering near 1.0 percent. This isn’t the sort of interest rate that is ordinarily associated with a debt problem.

That’s why readers are thankful for the information the NYT gave us in this article. If they had just relied on the data, they wouldn’t know these things about Japan’s economic situation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a news article promoting a trade agreement between the United States and the European Union. The article wrongly referred to the trade deal as a “free trade” agreement three times. The agreement is almost certain to include greater restrictions on intellectual property. These restrictions are forms of protection, they are the opposite of free trade. It would have been possible to both make the piece more accurate and save space by leaving out the word “free.”

It also told readers that European leaders:

“have argued that a free-trade deal would be both a cheap and a relatively painless way to stimulate growth. …

“Richard Bruton, the Irish minister for jobs, enterprise and innovation, said in a statement that a trade deal could lift the E.U. economy by €120 billion, or $160 billion, per year and the U.S. economy by $100 billion.”

The piece provides no clear context for these numbers, nor does it make it clear that these are one time gains that are projected to be realized over a substantial period of time. (Most of the terms in any agreement will be phased in over time.) These gains come to about 0.7 percent of GDP for the U.S. and 0.9 percent of GDP for the EU. Assuming it takes ten years to achieve them, the projections imply that the deal will increase growth in the U.S. by roughly 0.07 percentage points and in the EU by 0.09 percentage points.

This increment to growth will barely be noticeable and will have a minimal impact on employment. If the EU leaders are looking to this deal as a source of stimulus, as the article asserts, then they have a very poor understanding of economics.

The NYT ran a news article promoting a trade agreement between the United States and the European Union. The article wrongly referred to the trade deal as a “free trade” agreement three times. The agreement is almost certain to include greater restrictions on intellectual property. These restrictions are forms of protection, they are the opposite of free trade. It would have been possible to both make the piece more accurate and save space by leaving out the word “free.”

It also told readers that European leaders:

“have argued that a free-trade deal would be both a cheap and a relatively painless way to stimulate growth. …

“Richard Bruton, the Irish minister for jobs, enterprise and innovation, said in a statement that a trade deal could lift the E.U. economy by €120 billion, or $160 billion, per year and the U.S. economy by $100 billion.”

The piece provides no clear context for these numbers, nor does it make it clear that these are one time gains that are projected to be realized over a substantial period of time. (Most of the terms in any agreement will be phased in over time.) These gains come to about 0.7 percent of GDP for the U.S. and 0.9 percent of GDP for the EU. Assuming it takes ten years to achieve them, the projections imply that the deal will increase growth in the U.S. by roughly 0.07 percentage points and in the EU by 0.09 percentage points.

This increment to growth will barely be noticeable and will have a minimal impact on employment. If the EU leaders are looking to this deal as a source of stimulus, as the article asserts, then they have a very poor understanding of economics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión