At a time where the most obvious conflict over resources has been the enormous upward redistribution to the top 1 percent, the Los Angeles Times is working to promote conflict based on age. A piece on the budget battle was centered around the claim that the Republicans base of support is disproportionately older people who depend on Social Security and Medicare whose interests are pitted against those of younger voters who support the Democrats:

“At its core, the debate over the size of government and how to pay for it pits the interests of the huge baby boom generation, now mostly in their 50s and 60s, against the needs of the even larger cohort in their teens and 20s. With limited government money to spend, how much should go to paying medical bills for retirees versus subsidizing college loans, job training and healthcare for young families with children?”

In fact, the government is not up against any resource limits as the markets keep trying to tell people by lending the government vast amounts of money at extremely low interest rates. If the economy were near full employment, then the deficit would be less than 2.0 percent of GDP, a level that can be sustained forever.

Over the longer term deficits are projected to be a problem, but this is because of the projected explosion in health care costs, not the aging of the population. If U.S. per person health care costs were comparable to those in any other wealthy country we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficits. This suggests that there is a conflict between the interests of the public at large and the health care providers (e.g. the drug, insurance and medical supply companies and high paid medical specialists), but not between generations.

Finally, it is important to note that the cuts that have been proposed for Social Security and Medicare, such as raising the normal retirement age or the age of eligibility for Medicare would primarily hit the young, not people currently receiving benefits from these programs. Polls have shown that seniors often support these programs because they want to ensure that their children and grandchildren get the same benefits that they enjoy, not out of a selfish impulse to protect what they have.

At a time where the most obvious conflict over resources has been the enormous upward redistribution to the top 1 percent, the Los Angeles Times is working to promote conflict based on age. A piece on the budget battle was centered around the claim that the Republicans base of support is disproportionately older people who depend on Social Security and Medicare whose interests are pitted against those of younger voters who support the Democrats:

“At its core, the debate over the size of government and how to pay for it pits the interests of the huge baby boom generation, now mostly in their 50s and 60s, against the needs of the even larger cohort in their teens and 20s. With limited government money to spend, how much should go to paying medical bills for retirees versus subsidizing college loans, job training and healthcare for young families with children?”

In fact, the government is not up against any resource limits as the markets keep trying to tell people by lending the government vast amounts of money at extremely low interest rates. If the economy were near full employment, then the deficit would be less than 2.0 percent of GDP, a level that can be sustained forever.

Over the longer term deficits are projected to be a problem, but this is because of the projected explosion in health care costs, not the aging of the population. If U.S. per person health care costs were comparable to those in any other wealthy country we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficits. This suggests that there is a conflict between the interests of the public at large and the health care providers (e.g. the drug, insurance and medical supply companies and high paid medical specialists), but not between generations.

Finally, it is important to note that the cuts that have been proposed for Social Security and Medicare, such as raising the normal retirement age or the age of eligibility for Medicare would primarily hit the young, not people currently receiving benefits from these programs. Polls have shown that seniors often support these programs because they want to ensure that their children and grandchildren get the same benefits that they enjoy, not out of a selfish impulse to protect what they have.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

For some reason no one appears to be asking this obvious question in the context of Al Jazeera’s purchase of the Current TV station. According to the news reports, Al Jazeera does not intend to keep much, if any, of Current TV’s programming. That means it is willing to pay $500 million simply to be carried by the large cable providers. That implies that these providers have extraordinary market power. This should be raising lots of questions at the Federal Communications Commission.

For some reason no one appears to be asking this obvious question in the context of Al Jazeera’s purchase of the Current TV station. According to the news reports, Al Jazeera does not intend to keep much, if any, of Current TV’s programming. That means it is willing to pay $500 million simply to be carried by the large cable providers. That implies that these providers have extraordinary market power. This should be raising lots of questions at the Federal Communications Commission.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

What the hell is wrong with the NYT, are they working for the Campaign to Fix the Debt? The plan for Social Security and Medicare is for cuts, as in reduce spending, as in pay out fewer dollars, not random “changes” that could lead to either more or less spending. How does the term “changes” appear in this paragraph:

“That opening bid [in further budget negotiations] should restart talks with Congress on an overarching agreement that would lock in deficit reduction through additional revenue, changes to entitlement programs and more spending cuts, to be worked out by the relevant committees in Congress.”

Newspapers are supposed to be informing their readers, not trying to make their friends’ agenda more palatable. There is no excuse for the word “changes” to appear in this article.

What the hell is wrong with the NYT, are they working for the Campaign to Fix the Debt? The plan for Social Security and Medicare is for cuts, as in reduce spending, as in pay out fewer dollars, not random “changes” that could lead to either more or less spending. How does the term “changes” appear in this paragraph:

“That opening bid [in further budget negotiations] should restart talks with Congress on an overarching agreement that would lock in deficit reduction through additional revenue, changes to entitlement programs and more spending cuts, to be worked out by the relevant committees in Congress.”

Newspapers are supposed to be informing their readers, not trying to make their friends’ agenda more palatable. There is no excuse for the word “changes” to appear in this article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is continuing its drumbeat for deficit reduction devoting an entire article to the views of the business lobby without ever presenting the possibility that their claims may not be accurate. In fact the piece explicitly endorsed the business perspective wrongly warning readers in the first sentence that the deficit deal “won’t unlock investment.”

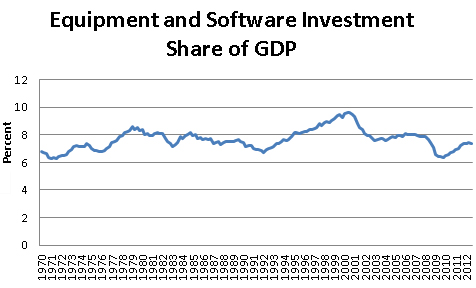

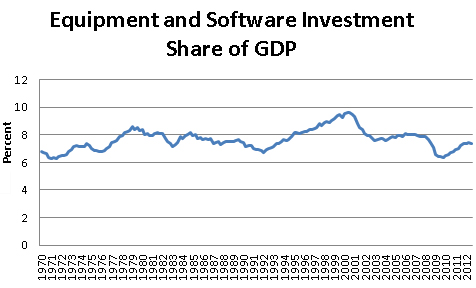

This assertion can easily be shown to be wrong since fans of Commerce Department data know that investment is not “locked.” In fact, equipment and software investment is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. This is quite impressive since many sectors of the economy still have large amounts of excess capacity.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The relatively strong pace of investment suggests that there is nothing to be “unlocked” by the sort of budget agreement the Post would like to see. It is of course advantageous to proponents of such a deal to have the public believe that there would be a flood of investment if Congress pushed the spending cuts they wanted.

The Washington Post is continuing its drumbeat for deficit reduction devoting an entire article to the views of the business lobby without ever presenting the possibility that their claims may not be accurate. In fact the piece explicitly endorsed the business perspective wrongly warning readers in the first sentence that the deficit deal “won’t unlock investment.”

This assertion can easily be shown to be wrong since fans of Commerce Department data know that investment is not “locked.” In fact, equipment and software investment is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. This is quite impressive since many sectors of the economy still have large amounts of excess capacity.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The relatively strong pace of investment suggests that there is nothing to be “unlocked” by the sort of budget agreement the Post would like to see. It is of course advantageous to proponents of such a deal to have the public believe that there would be a flood of investment if Congress pushed the spending cuts they wanted.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an analysis of the fiscal cliff deal David Leonhardt told readers that:

“Having won this round, Democrats still have compromises to offer Republicans in the next one, like changes to Social Security.”

Actually Democrats, or at least progressive Democrats, are not concerned about “changes” to Social Security, they would be very happy with an increase in benefits, especially for lower income retirees. Democrats are worried about “cuts” to Social Security. It is amazing that the NYT refuses to make this fact clear to its readers.

This piece also inaccurately asserts that:

“In the 2008 campaign, Mr. Obama said that his top priority as president would be to “create bottom-up economic growth” and reduce inequality. He has governed as such.”

This is at best debatable. President Obama bailed out the big Wall Street banks, allowing them to get trillions of dollars in loans at below market interest rates. This massive subsidy allowed many of the richest people in the country to preserve their wealth when market forces left to themselves almost certainly would have put most of the major banks out of business.

Obama has also refused to make a reduction in the value of the dollar a top goal in trade policy. A lower valued dollar would create millions of new manufacturing jobs by making U.S. goods more competitive in the world economy. This would provide a strong boost to labor demand and wages.

Obama has also pushed trade agreements that have a main goal of increasing patent and copyright protections. This will lead to more rents going to drug companies, software companies and the entertainment industry, raising prices for consumers. He also has done nothing to reduce the protectionist barriers that allow doctors in the United States to earn twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries, pushing up health care costs to consumers by $80 billion a year.

Of course President Obama has also embraced the absurd claim that reducing the deficit is a top priority, abandoning the route of economic stimulus, even though he knows that the large current deficits are entirely the result of the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble.

Looking at a longer list of Obama administration policies, it is very difficult to support the claim that he has governed in a way that promotes the middle class.

In an analysis of the fiscal cliff deal David Leonhardt told readers that:

“Having won this round, Democrats still have compromises to offer Republicans in the next one, like changes to Social Security.”

Actually Democrats, or at least progressive Democrats, are not concerned about “changes” to Social Security, they would be very happy with an increase in benefits, especially for lower income retirees. Democrats are worried about “cuts” to Social Security. It is amazing that the NYT refuses to make this fact clear to its readers.

This piece also inaccurately asserts that:

“In the 2008 campaign, Mr. Obama said that his top priority as president would be to “create bottom-up economic growth” and reduce inequality. He has governed as such.”

This is at best debatable. President Obama bailed out the big Wall Street banks, allowing them to get trillions of dollars in loans at below market interest rates. This massive subsidy allowed many of the richest people in the country to preserve their wealth when market forces left to themselves almost certainly would have put most of the major banks out of business.

Obama has also refused to make a reduction in the value of the dollar a top goal in trade policy. A lower valued dollar would create millions of new manufacturing jobs by making U.S. goods more competitive in the world economy. This would provide a strong boost to labor demand and wages.

Obama has also pushed trade agreements that have a main goal of increasing patent and copyright protections. This will lead to more rents going to drug companies, software companies and the entertainment industry, raising prices for consumers. He also has done nothing to reduce the protectionist barriers that allow doctors in the United States to earn twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries, pushing up health care costs to consumers by $80 billion a year.

Of course President Obama has also embraced the absurd claim that reducing the deficit is a top priority, abandoning the route of economic stimulus, even though he knows that the large current deficits are entirely the result of the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble.

Looking at a longer list of Obama administration policies, it is very difficult to support the claim that he has governed in a way that promotes the middle class.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, it is so frustrating that President Obama keeps missing the opportunity to whack the elderly. Of course fans of arithmetic know that the story of projected long-term budget deficits is the broken U.S. health care system. If we paid the same amount per person for our care as people in other wealthy countries we would be looking at long-term surpluses, not deficits. And, if we can’t fix our health care system because groups like the pharmaceutical industry and the doctors are too powerful, we could always go the route of trade to take advantage of lower costs elsewhere. Unfortunately, public policy is dominated by protectionists like Samuelson, who obstruct such trade. But these political obstacles do not change the truth. The budget problem is health care, health care and health care.

Yes, it is so frustrating that President Obama keeps missing the opportunity to whack the elderly. Of course fans of arithmetic know that the story of projected long-term budget deficits is the broken U.S. health care system. If we paid the same amount per person for our care as people in other wealthy countries we would be looking at long-term surpluses, not deficits. And, if we can’t fix our health care system because groups like the pharmaceutical industry and the doctors are too powerful, we could always go the route of trade to take advantage of lower costs elsewhere. Unfortunately, public policy is dominated by protectionists like Samuelson, who obstruct such trade. But these political obstacles do not change the truth. The budget problem is health care, health care and health care.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Those who hoped that one of the new year’s resolutions at the Post would be more honest budget reporting would be disappointed by today’s paper. While this budget piece starts off well with a headline about taming the threat from the debt ceiling and high unemployment, the expression “tame the debt” appears twice on the second page. While it does note that the projected rise in health care costs is a major cause of the projected deficits, it does not note that it is really the only cause. It also would have been helpful to point out that the only reason for the large deficits that we are now seeing is the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble.

Those who hoped that one of the new year’s resolutions at the Post would be more honest budget reporting would be disappointed by today’s paper. While this budget piece starts off well with a headline about taming the threat from the debt ceiling and high unemployment, the expression “tame the debt” appears twice on the second page. While it does note that the projected rise in health care costs is a major cause of the projected deficits, it does not note that it is really the only cause. It also would have been helpful to point out that the only reason for the large deficits that we are now seeing is the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Some of us didn’t take the skills deficit seriously, but David Brooks shows us that it is a real problem. Apparently the New York Times cannot find a conservative columnist who can deal with basic issues of logic and arithmetic. Brooks is very upset because the budget deal apparently does not include any cuts in Medicare.

He also is very angry that so many people insist on relying on arithmetic and pointing out that the “$1 trillion” deficits are almost entirely due to the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble and not some fundamental imbalance of taxes and spending. He scoffs:

“They have found that the original Keynesian rationale for these deficits provides a perfect cover for permanent deficit-living.”

Wow, those damn math nerds!

On the more fundamental question of the long-term deficit projections that have Brooks so excited, fans of arithmetic keep pointing out, to Brooks’ frustration and anger, that it is all due to our broken health care system. If our per person health care costs were comparable to those in Germany, Canada, or any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses in the future, not the enormous deficits that have Brooks so excited.

Serious people therefore talk about fixing our health care system. (Trade is one possible route, although committed protectionists like Brooks apparently never even consider it.) In fact, recent cost numbers suggest that we may already be on the right track. But Brooks doesn’t look at numbers. He is really angry because the public doesn’t want to suffer and politicians who want to keep their jobs are not anxious to make them suffer.

It’s best to let Brooks tell the story himself:

“Ultimately, we should blame the American voters. …

“Most members of Congress are responding efficiently to the popular will. A large number of reactionary Democrats reject any measure to touch Medicare or other entitlement programs. A large number of impotent Republicans talk about reducing the debt, but are incapable of forging a deal that balances tax increases with spending cuts.”

Some of us didn’t take the skills deficit seriously, but David Brooks shows us that it is a real problem. Apparently the New York Times cannot find a conservative columnist who can deal with basic issues of logic and arithmetic. Brooks is very upset because the budget deal apparently does not include any cuts in Medicare.

He also is very angry that so many people insist on relying on arithmetic and pointing out that the “$1 trillion” deficits are almost entirely due to the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble and not some fundamental imbalance of taxes and spending. He scoffs:

“They have found that the original Keynesian rationale for these deficits provides a perfect cover for permanent deficit-living.”

Wow, those damn math nerds!

On the more fundamental question of the long-term deficit projections that have Brooks so excited, fans of arithmetic keep pointing out, to Brooks’ frustration and anger, that it is all due to our broken health care system. If our per person health care costs were comparable to those in Germany, Canada, or any other wealthy country we would be looking at huge budget surpluses in the future, not the enormous deficits that have Brooks so excited.

Serious people therefore talk about fixing our health care system. (Trade is one possible route, although committed protectionists like Brooks apparently never even consider it.) In fact, recent cost numbers suggest that we may already be on the right track. But Brooks doesn’t look at numbers. He is really angry because the public doesn’t want to suffer and politicians who want to keep their jobs are not anxious to make them suffer.

It’s best to let Brooks tell the story himself:

“Ultimately, we should blame the American voters. …

“Most members of Congress are responding efficiently to the popular will. A large number of reactionary Democrats reject any measure to touch Medicare or other entitlement programs. A large number of impotent Republicans talk about reducing the debt, but are incapable of forging a deal that balances tax increases with spending cuts.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steve Rattner had a series of mostly useful charts in the NYT this morning describing the state of the economy. The major exception is the one on Social Security shown below.

It is not clear what information this chart is supposed to convey. The average annual benefit in 2012 for a retired worker was $14,760 according to the Social Security Administration. It’s not clear where Rattner got $23,135. The chart also shows adopting a chained CPI, presumably for adjusting the annual cost of living adjustment, would have led to a 4.0 percent cut in benefits by 2011. This is a considerably larger cut than is usually estimated, since the change would only apply to benefits after retirement.

It is also not clear why anyone would use median income (not defined) as a reference point. The point of Social Security is to protect retirees from economic fluctuations like the severe downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble. While more competent economic policy would have provided more protection to workers also, we have Social Security because we recognize that retirees have fewer options to boost their income (i.e. work more) than the working age population. Also, since the chart purports to show averarge benefits it would be more reasonable to at least include average income.

This piece also inaccurately refers to the report from the Bowles-Simpson commission. There was no report from the Bowles-Simpson commission since no plan received the necessary majority support.

Steve Rattner had a series of mostly useful charts in the NYT this morning describing the state of the economy. The major exception is the one on Social Security shown below.

It is not clear what information this chart is supposed to convey. The average annual benefit in 2012 for a retired worker was $14,760 according to the Social Security Administration. It’s not clear where Rattner got $23,135. The chart also shows adopting a chained CPI, presumably for adjusting the annual cost of living adjustment, would have led to a 4.0 percent cut in benefits by 2011. This is a considerably larger cut than is usually estimated, since the change would only apply to benefits after retirement.

It is also not clear why anyone would use median income (not defined) as a reference point. The point of Social Security is to protect retirees from economic fluctuations like the severe downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble. While more competent economic policy would have provided more protection to workers also, we have Social Security because we recognize that retirees have fewer options to boost their income (i.e. work more) than the working age population. Also, since the chart purports to show averarge benefits it would be more reasonable to at least include average income.

This piece also inaccurately refers to the report from the Bowles-Simpson commission. There was no report from the Bowles-Simpson commission since no plan received the necessary majority support.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión