In his year-end report Chief Justice John Roberts bizarrely complained about the “fiscal cliff” and the national debt, wrongly asserting that:

““No one seriously doubts that the country’s fiscal ledger has gone awry.”

Of course everyone familiar with budget data knows that the reason that deficit exploded was the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble. It would have been appropriate for the NYT to present the views of an economic expert who could have pointed out that Justice Roberts clearly does not understand the economy or the budget.

In his year-end report Chief Justice John Roberts bizarrely complained about the “fiscal cliff” and the national debt, wrongly asserting that:

““No one seriously doubts that the country’s fiscal ledger has gone awry.”

Of course everyone familiar with budget data knows that the reason that deficit exploded was the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble. It would have been appropriate for the NYT to present the views of an economic expert who could have pointed out that Justice Roberts clearly does not understand the economy or the budget.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is the gist of his column today. He presents some evidence that the gap in costs between the United States and the developing world, most importantly China, has been reduced and therefore jobs are coming back to the United States. It’s very hard to understand the negative in this story. It could mean that a trade deficit that was leading to ever more foreign indebtedness is beginning to moderate. It’s not clear why this would be bad.

The complaint is especially ironic coming from Samuelson, who has long been very upset about government budget defiits in the United States.It is difficult to imagine a scenario where the budget deficit moves closer to balance that does not also involve the trade deficit moving closer to balance. The only alternative way to make up for the demand lost to the trade deficit would be with negative private sector savings.

That is the gist of his column today. He presents some evidence that the gap in costs between the United States and the developing world, most importantly China, has been reduced and therefore jobs are coming back to the United States. It’s very hard to understand the negative in this story. It could mean that a trade deficit that was leading to ever more foreign indebtedness is beginning to moderate. It’s not clear why this would be bad.

The complaint is especially ironic coming from Samuelson, who has long been very upset about government budget defiits in the United States.It is difficult to imagine a scenario where the budget deficit moves closer to balance that does not also involve the trade deficit moving closer to balance. The only alternative way to make up for the demand lost to the trade deficit would be with negative private sector savings.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT doesn’t seem to keep up to date with writings on the budget deficit even in its own paper. As I have often pointed out, the large budget deficits of recent years are entirely attributable to the plunge in the economy caused by the collapse of the housing bubble. Paul Krugman has recently been harping on this point in his NYT column and blog. For this reason, its news story claiming that:

“Years of increased spending on everything from wars to expanded entitlement programs — combined with protracted, stubborn unemployment and a nation of workers whose earning power and home values have plummeted in recent years — have persuaded lawmakers in both parties that fiscal policy is the most pressing domestic concern.”

Of course the “years of increased spending” would be beside the point if it were not for the economic downturn. The NYT badly misled its readers in making this assertion.

The article also misled readers in the next sentence which asserts:

“But a fundamental ideological chasm between the majority of lawmakers and an empowered group of Congressional Republicans — fueled by some Tea Party victories in both chambers in 2010 — has made it more difficult than ever to reach fiscal and budgetary compromises.”

Actually, the vast majority of Tea Party backers agree with the vast majority of Democrats in their opposition to cuts in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The main difference is that the Tea Party backers seem to believe that there is some other area of government spending, other than defense, that can be cut back to reduce or eliminate the budget deficit. Of course this is not true. However the nature of the gap between most Democrats and Tea Party backers is informational, not ideological.

This makes the position of Republicans in Congress especially difficult. They need to produce spending cuts, but not in the programs that the Tea Party backers support and often depend upon. Since this is not possible, it makes the politics very hard for them.

The NYT doesn’t seem to keep up to date with writings on the budget deficit even in its own paper. As I have often pointed out, the large budget deficits of recent years are entirely attributable to the plunge in the economy caused by the collapse of the housing bubble. Paul Krugman has recently been harping on this point in his NYT column and blog. For this reason, its news story claiming that:

“Years of increased spending on everything from wars to expanded entitlement programs — combined with protracted, stubborn unemployment and a nation of workers whose earning power and home values have plummeted in recent years — have persuaded lawmakers in both parties that fiscal policy is the most pressing domestic concern.”

Of course the “years of increased spending” would be beside the point if it were not for the economic downturn. The NYT badly misled its readers in making this assertion.

The article also misled readers in the next sentence which asserts:

“But a fundamental ideological chasm between the majority of lawmakers and an empowered group of Congressional Republicans — fueled by some Tea Party victories in both chambers in 2010 — has made it more difficult than ever to reach fiscal and budgetary compromises.”

Actually, the vast majority of Tea Party backers agree with the vast majority of Democrats in their opposition to cuts in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The main difference is that the Tea Party backers seem to believe that there is some other area of government spending, other than defense, that can be cut back to reduce or eliminate the budget deficit. Of course this is not true. However the nature of the gap between most Democrats and Tea Party backers is informational, not ideological.

This makes the position of Republicans in Congress especially difficult. They need to produce spending cuts, but not in the programs that the Tea Party backers support and often depend upon. Since this is not possible, it makes the politics very hard for them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A WSJ article told readers that the “fiscal cliff” has already caused damage to the economy. The piece began:

“The damage may already be done.

“Even if lawmakers manage to avoid most of the $500 billion in tax increases and spending cuts set to take effect this week, the risks to the U.S. economy have risen as consumers and investors recoil from Washington’s latest budget spectacle.”

That ain’t what the data show. The piece trumpets the plunge in consumer confidence in December, while noting in passing:

“The research group (the Conference Board) said Americans’ outlook for the economy ‘plummeted’ despite a positive view about current economic conditions.”

Of course it is only the current conditions index that bears any relation to consumer spending. The expectations index is driven primarily by news reporting, like hysterical accounts of the implications of the fiscal cliff. It has virtually no relationship to spending.

Contrary to the implication of this piece, the Commerce Department reported that investment in capital goods, excluding aircraft, was up 2.7 percent in December and 3.2 percent in November, suggesting little concern about the fiscal cliff. While the stock market has been down somewhat in recent weeks, short-term fluctuations in the market have almost no meaning for the economy.

In short, we should all appreciate the WSJ’s efforts to hype the fiscal cliff, but they should place them on the fiction page.

A WSJ article told readers that the “fiscal cliff” has already caused damage to the economy. The piece began:

“The damage may already be done.

“Even if lawmakers manage to avoid most of the $500 billion in tax increases and spending cuts set to take effect this week, the risks to the U.S. economy have risen as consumers and investors recoil from Washington’s latest budget spectacle.”

That ain’t what the data show. The piece trumpets the plunge in consumer confidence in December, while noting in passing:

“The research group (the Conference Board) said Americans’ outlook for the economy ‘plummeted’ despite a positive view about current economic conditions.”

Of course it is only the current conditions index that bears any relation to consumer spending. The expectations index is driven primarily by news reporting, like hysterical accounts of the implications of the fiscal cliff. It has virtually no relationship to spending.

Contrary to the implication of this piece, the Commerce Department reported that investment in capital goods, excluding aircraft, was up 2.7 percent in December and 3.2 percent in November, suggesting little concern about the fiscal cliff. While the stock market has been down somewhat in recent weeks, short-term fluctuations in the market have almost no meaning for the economy.

In short, we should all appreciate the WSJ’s efforts to hype the fiscal cliff, but they should place them on the fiction page.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, it’s the season of the whopper here in DC as the dreaded Mayan apocalypse (a.k.a. “fiscal cliff) approaches. According to the Washington Post, unnamed Pentagon officials warned that it may have to furlough up to 800,000 civilian employees if the budget sequester goes into effect this week. That sounds really scary since the Labor Department says that the Defense Department has less than 560,000 civilian employees. How is this supposed to work exactly?

[Note: Typos corrected, thanks Elizabeth.]

Yes, it’s the season of the whopper here in DC as the dreaded Mayan apocalypse (a.k.a. “fiscal cliff) approaches. According to the Washington Post, unnamed Pentagon officials warned that it may have to furlough up to 800,000 civilian employees if the budget sequester goes into effect this week. That sounds really scary since the Labor Department says that the Defense Department has less than 560,000 civilian employees. How is this supposed to work exactly?

[Note: Typos corrected, thanks Elizabeth.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post had a major business section article promising that 2013 could be the year of a “rip-roaring” recovery, if nothing bad gets in the way. While there are reasons to think that 2013 could be better than the prior two years, it’s not clear that “rip-roaring” would be the right term to apply.

The high-end of growth forecasts is around 3.0 percent. This assumes that the budget standoff is resolved relatively quickly on terms that do little damage to the recovery. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) the economy is currently operating about 6 percent below potential GDP. CBO puts potential growth at 2.4 percent, which means that if the economy does grow at a 3.0 percent rate we would be reducing the output gap by 0.6 percentage points.

At this pace it would take us 10 years to get back to potential GDP. When the economy has suffered severe downturns in the past, for example in 1974-75 and 1981-82, the economy had stretches of growth in the range of 7-8 percent. That sort of growth could reasonably be described as “rip-roaring,” 3.0 percent doesn’t really fit the bill.

There are a few other items that are not exactly right in this piece. It rightly notes the improvement in the housing sector, which is likely to continue into 2013, but neglects to mention the vacancy rate. While there has been a considerable decline in the vacancy rate from the record levels reached in 2010, the vacancy rate is still far above its pre-bubble level. This will be a drag on construction as many people forming their own household can turn to units that are currently vacant rather than newly constructed units.

The piece also holds out the hope that consumer spending will rebound based on the fact that consumers have paid down much of their debt from the bubble years. This claim is bizarre for two reasons. First, it is not just debt that affects spending. It is also wealth. A debt of $1 million would leave most of us struggling to meet our payments. By contrast, if Bill Gates had $1 million in debt it would not affect his consumption at all, because he also has $50 billion in assets. The story of the downturn in consumption is that households have lost close to $8 trillion in housing equity. This explains the downturn in consumption from its bubble peaks. The role of debt is very much secondary.

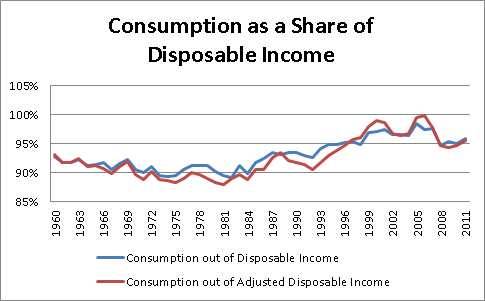

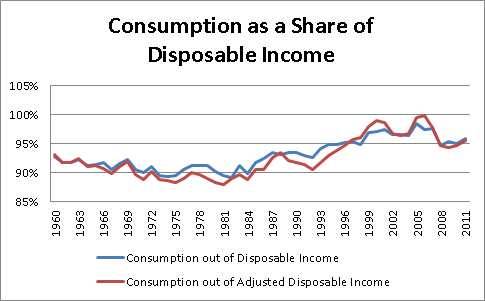

The other reason why the prediction of an upswing in consumption is bizarre is that consumption is already at an unusually high level relative to disposable income. If anything, it should be surprising that consumption is so high, given the loss of so much housing wealth.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Finally, the piece seems to have reversed the relative impact on growth and unemployment associated with the ending of the payroll tax cut, telling readers:

“The CBO estimates that the end of the payroll tax holiday, combined with an extension of unemployment benefits, could cost the economy 0.7 percentage points of growth and increase the jobless rate by 0.8 percentage points over what it otherwise would have been.”

Usually the impact on growth is roughly twice the size of the impact on the unemployment rate. While it is plausible that CBO projected that the end of the payroll tax cut would slow growth by 0.7 percentage points, it is not plausible that this would be associated with a 0.8 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate.

The Post had a major business section article promising that 2013 could be the year of a “rip-roaring” recovery, if nothing bad gets in the way. While there are reasons to think that 2013 could be better than the prior two years, it’s not clear that “rip-roaring” would be the right term to apply.

The high-end of growth forecasts is around 3.0 percent. This assumes that the budget standoff is resolved relatively quickly on terms that do little damage to the recovery. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) the economy is currently operating about 6 percent below potential GDP. CBO puts potential growth at 2.4 percent, which means that if the economy does grow at a 3.0 percent rate we would be reducing the output gap by 0.6 percentage points.

At this pace it would take us 10 years to get back to potential GDP. When the economy has suffered severe downturns in the past, for example in 1974-75 and 1981-82, the economy had stretches of growth in the range of 7-8 percent. That sort of growth could reasonably be described as “rip-roaring,” 3.0 percent doesn’t really fit the bill.

There are a few other items that are not exactly right in this piece. It rightly notes the improvement in the housing sector, which is likely to continue into 2013, but neglects to mention the vacancy rate. While there has been a considerable decline in the vacancy rate from the record levels reached in 2010, the vacancy rate is still far above its pre-bubble level. This will be a drag on construction as many people forming their own household can turn to units that are currently vacant rather than newly constructed units.

The piece also holds out the hope that consumer spending will rebound based on the fact that consumers have paid down much of their debt from the bubble years. This claim is bizarre for two reasons. First, it is not just debt that affects spending. It is also wealth. A debt of $1 million would leave most of us struggling to meet our payments. By contrast, if Bill Gates had $1 million in debt it would not affect his consumption at all, because he also has $50 billion in assets. The story of the downturn in consumption is that households have lost close to $8 trillion in housing equity. This explains the downturn in consumption from its bubble peaks. The role of debt is very much secondary.

The other reason why the prediction of an upswing in consumption is bizarre is that consumption is already at an unusually high level relative to disposable income. If anything, it should be surprising that consumption is so high, given the loss of so much housing wealth.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Finally, the piece seems to have reversed the relative impact on growth and unemployment associated with the ending of the payroll tax cut, telling readers:

“The CBO estimates that the end of the payroll tax holiday, combined with an extension of unemployment benefits, could cost the economy 0.7 percentage points of growth and increase the jobless rate by 0.8 percentage points over what it otherwise would have been.”

Usually the impact on growth is roughly twice the size of the impact on the unemployment rate. While it is plausible that CBO projected that the end of the payroll tax cut would slow growth by 0.7 percentage points, it is not plausible that this would be associated with a 0.8 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Readers of the NYT article on the latest developments in the budget negotiations may have not realized that the Republican demands for changing the indexation formula for the Social Security cost of living adjustment is equivalent to a 3 percent cut in benefits for a typical retiree. The new formula would lower the adjustment by approximately 0.3 percentage points each year. This means that a retiree would be receiving 3 percent lower benefits after 10 years, 6 percent lower benefits after 20 years and 9 percent lower benefits after 30 years. If a typical retiree collects benefits for 20 years then the average reduction in benefits would be about 3.0 percent.

The piece also claims that:

“Both sides worry that the confrontational tone that the president took on “Meet the Press” was not helpful.”

It only included comments from Republicans who didn’t like President Obama’s tone. There were no Democrats cited who had this attitude, even off the record.

Readers of the NYT article on the latest developments in the budget negotiations may have not realized that the Republican demands for changing the indexation formula for the Social Security cost of living adjustment is equivalent to a 3 percent cut in benefits for a typical retiree. The new formula would lower the adjustment by approximately 0.3 percentage points each year. This means that a retiree would be receiving 3 percent lower benefits after 10 years, 6 percent lower benefits after 20 years and 9 percent lower benefits after 30 years. If a typical retiree collects benefits for 20 years then the average reduction in benefits would be about 3.0 percent.

The piece also claims that:

“Both sides worry that the confrontational tone that the president took on “Meet the Press” was not helpful.”

It only included comments from Republicans who didn’t like President Obama’s tone. There were no Democrats cited who had this attitude, even off the record.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a fascinating piece on how Questcor raised the price of its drug Acthar to $28,000 per prescription. Since it raised its price it has begun pushing the drug for a number of uses for which it may not be suited. It is able to do this because the drug was initially approved by the FDA in 1952, before restrictions on off-label marketing applied.

Until recently the drug sold for less than $2,000 per prescription. (Apparently, the manufacturing process is complicated and expensive.) At this price the drug company had little incentive to try to promote its drug for different uses. It is only the high price which provides the incentive for mis-marketing the drug.

The NYT had a fascinating piece on how Questcor raised the price of its drug Acthar to $28,000 per prescription. Since it raised its price it has begun pushing the drug for a number of uses for which it may not be suited. It is able to do this because the drug was initially approved by the FDA in 1952, before restrictions on off-label marketing applied.

Until recently the drug sold for less than $2,000 per prescription. (Apparently, the manufacturing process is complicated and expensive.) At this price the drug company had little incentive to try to promote its drug for different uses. It is only the high price which provides the incentive for mis-marketing the drug.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

William D. Cohan had a bizarre opinion piece in the Sunday Post claiming that the Fed’s low interest rate policy was hurting savers and helping hedge funds. The gist of the story is that low interest rates hurt small savers with bank deposits while they make it easier for hedge funds to borrow money to speculate. Both sides seem more than a bit off the mark.

On the small savers story, it’s not clear how much anyone could be hurt. It’s not clear what interest rate Cohan would expect the Fed to run in a badly depressed economy (he complains about an “artificially” low rate, which seems to imply that there is a natural rate out there somewhere), but let’s assume that 2 percent would be Cohan’s preferred rate. If a saver has $40,000 in the bank (this would put them way above the bulk of the population in terms of their holdings of financial assets), Bernanke’s zero interest policy is costing them $800 a year. That’s not trivial, but hardly a disaster either.

Even this loss assumes that all of their savings are in short term deposits. If they hold long-term bonds they have seen their price soar, at least in part because of Bernanke’s policy. Also the low interest rate policy has almost certainly given a boost to the stock market as well.

On the hedge fund side, investors have benefited from lower interest rates, but this is hardly necessary for them to profit. Hedge funds made plenty of money in the higher interest rate environment of 2006-2007 as well as the late 90s. The zero interest rate policy is certainly not necessary for them to earn hefty profits.

The biggest gainers from the low interest rate policy are probably the millions of homeowners who have been able to refinance at interest rates that are 1-2 percentage points lower than their previous mortgage. A 1.5 percentage point drop in interest rates on a $200,000 mortgage would save a homeowner $3,000 a year in interest payments. For this reason it is very difficult to see Bernanke’s low interest rate policy as one designed to primarily benefit the wealthy.

William D. Cohan had a bizarre opinion piece in the Sunday Post claiming that the Fed’s low interest rate policy was hurting savers and helping hedge funds. The gist of the story is that low interest rates hurt small savers with bank deposits while they make it easier for hedge funds to borrow money to speculate. Both sides seem more than a bit off the mark.

On the small savers story, it’s not clear how much anyone could be hurt. It’s not clear what interest rate Cohan would expect the Fed to run in a badly depressed economy (he complains about an “artificially” low rate, which seems to imply that there is a natural rate out there somewhere), but let’s assume that 2 percent would be Cohan’s preferred rate. If a saver has $40,000 in the bank (this would put them way above the bulk of the population in terms of their holdings of financial assets), Bernanke’s zero interest policy is costing them $800 a year. That’s not trivial, but hardly a disaster either.

Even this loss assumes that all of their savings are in short term deposits. If they hold long-term bonds they have seen their price soar, at least in part because of Bernanke’s policy. Also the low interest rate policy has almost certainly given a boost to the stock market as well.

On the hedge fund side, investors have benefited from lower interest rates, but this is hardly necessary for them to profit. Hedge funds made plenty of money in the higher interest rate environment of 2006-2007 as well as the late 90s. The zero interest rate policy is certainly not necessary for them to earn hefty profits.

The biggest gainers from the low interest rate policy are probably the millions of homeowners who have been able to refinance at interest rates that are 1-2 percentage points lower than their previous mortgage. A 1.5 percentage point drop in interest rates on a $200,000 mortgage would save a homeowner $3,000 a year in interest payments. For this reason it is very difficult to see Bernanke’s low interest rate policy as one designed to primarily benefit the wealthy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Those of us old-timers who think that news reporting is about conveying information were seriously bothered by an NYT article on a plan for a one-year extension of the current farm bill. These bills usually run for 5 years. There had been plans to reduce the subsidies from the level in the previous bill in order to reduce the budget deficit. A one-year extension will not allow these savings to be realized.

However readers of this article would be unlikely to have any idea of the budgetary impact of this extension. The piece told readers;

“An extension would most likely wipe out billions of dollars in savings that lawmakers in both the Senate and House had achieved by cutting some farm and nutrition programs. The Senate bill would have saved about $23 billion. About $4.5 billion in savings would have come from cuts to the food stamp program.”

Okay, most people don’t have a clue how large or small these numbers are. If the point is informing readers why not express the numbers as a share of the budget. NYT readers understand percentages.

But this complaint can be directed at most budget reporting. What makes this piece stand out is that it gives readers no idea of the time frame. Would the savings of $23 billion come in the first year or is this over 5 years? The article provides no clue as to the answer. (I’m pretty sure it’s the latter.)

Anyhow, it should not have been too difficult to explicitly indicate the time-frame over which these savings are expected to take place. As it reads, this article provides almost no useful information to readers about the implication of the proposed extension on the farm bill.

Those of us old-timers who think that news reporting is about conveying information were seriously bothered by an NYT article on a plan for a one-year extension of the current farm bill. These bills usually run for 5 years. There had been plans to reduce the subsidies from the level in the previous bill in order to reduce the budget deficit. A one-year extension will not allow these savings to be realized.

However readers of this article would be unlikely to have any idea of the budgetary impact of this extension. The piece told readers;

“An extension would most likely wipe out billions of dollars in savings that lawmakers in both the Senate and House had achieved by cutting some farm and nutrition programs. The Senate bill would have saved about $23 billion. About $4.5 billion in savings would have come from cuts to the food stamp program.”

Okay, most people don’t have a clue how large or small these numbers are. If the point is informing readers why not express the numbers as a share of the budget. NYT readers understand percentages.

But this complaint can be directed at most budget reporting. What makes this piece stand out is that it gives readers no idea of the time frame. Would the savings of $23 billion come in the first year or is this over 5 years? The article provides no clue as to the answer. (I’m pretty sure it’s the latter.)

Anyhow, it should not have been too difficult to explicitly indicate the time-frame over which these savings are expected to take place. As it reads, this article provides almost no useful information to readers about the implication of the proposed extension on the farm bill.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión