That’s undoubtedly what readers are asking after seeing this strange and inaccurate phrase appear yet again in an article about the latest tax plan Speaker Boehner put forward. Of course it is inaccurate since it implies that debt and deficits have been out of control.

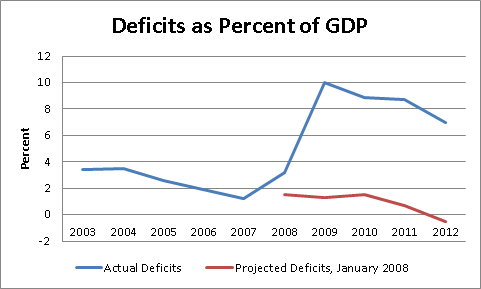

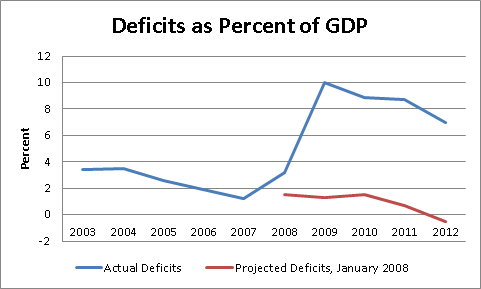

As every budget analyst knows, deficits were actually quite modest until the economy plummeted in 2008 following the collapse of the housing bubble. The deficit in 2007 was just 1.2 percent of GDP. The economy can run deficits of this size forever, since the debt to GDP ratio was actually falling. The deficit was projected to remain low for the next several years until the projected expiration of the Bush tax cuts pushed the budget into surplus in 2012.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

There have been no large unfunded increases in spending nor permanent tax cuts since these projections were made. The sole reason that the deficits came in much higher than projected was the impact of the recession on tax and spending and the stimulus measures taken to counter the downturn.

The Post has consistently misrepresented the nature of current deficits. This helps to promote its agenda of cutting Social Security and Medicare.

The Post also misrepresented the risks of missing the December 31 deadline of reaching a budget deal. It told readers:

“If no action is taken before the end of the year, taxes will rise for nearly 90 percent of taxpayers in January, potentially sparking a new recession, according to many economists.”

In fact it is not clear that any economists say that missing the deadline will cause a recession. The Congressional Budget Office and others have projected that if the higher tax rates and spending cuts remain in place all year that the economy will likely fall into a recession. They did not say that this would be the result of waiting one or two weeks into January to work out a deal.

Most analysts think that President Obama’s negotiating position will improve after the tax cuts expire. If this is the case then trying to maintain pressure on President Obama to reach a deal before the end of the year would also advance the Post’s agenda for cutting Social Security and Medicare.

That’s undoubtedly what readers are asking after seeing this strange and inaccurate phrase appear yet again in an article about the latest tax plan Speaker Boehner put forward. Of course it is inaccurate since it implies that debt and deficits have been out of control.

As every budget analyst knows, deficits were actually quite modest until the economy plummeted in 2008 following the collapse of the housing bubble. The deficit in 2007 was just 1.2 percent of GDP. The economy can run deficits of this size forever, since the debt to GDP ratio was actually falling. The deficit was projected to remain low for the next several years until the projected expiration of the Bush tax cuts pushed the budget into surplus in 2012.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

There have been no large unfunded increases in spending nor permanent tax cuts since these projections were made. The sole reason that the deficits came in much higher than projected was the impact of the recession on tax and spending and the stimulus measures taken to counter the downturn.

The Post has consistently misrepresented the nature of current deficits. This helps to promote its agenda of cutting Social Security and Medicare.

The Post also misrepresented the risks of missing the December 31 deadline of reaching a budget deal. It told readers:

“If no action is taken before the end of the year, taxes will rise for nearly 90 percent of taxpayers in January, potentially sparking a new recession, according to many economists.”

In fact it is not clear that any economists say that missing the deadline will cause a recession. The Congressional Budget Office and others have projected that if the higher tax rates and spending cuts remain in place all year that the economy will likely fall into a recession. They did not say that this would be the result of waiting one or two weeks into January to work out a deal.

Most analysts think that President Obama’s negotiating position will improve after the tax cuts expire. If this is the case then trying to maintain pressure on President Obama to reach a deal before the end of the year would also advance the Post’s agenda for cutting Social Security and Medicare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The top of the hour news segment on Morning Edition told listeners that forecasters have predicted that failing to meet the December 31st cutoff on budget negotiations would throw the economy back into recession (sorry, no link). This is not true. The projections for a recession assume that there is no deal on taxes and spending throughout 2013. They did not predict what would happen if it takes a few days or weeks in 2013 to come to an agreement that reversed most of the tax increases and spending cuts that go into effect at the end of the year.

This is a simple and important distinction. It is incredible that NPR could not find news writers who could get it right.

The top of the hour news segment on Morning Edition told listeners that forecasters have predicted that failing to meet the December 31st cutoff on budget negotiations would throw the economy back into recession (sorry, no link). This is not true. The projections for a recession assume that there is no deal on taxes and spending throughout 2013. They did not predict what would happen if it takes a few days or weeks in 2013 to come to an agreement that reversed most of the tax increases and spending cuts that go into effect at the end of the year.

This is a simple and important distinction. It is incredible that NPR could not find news writers who could get it right.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is having trouble with numbers again. It told readers that the bill passed by the Senate in the summer would restore the Clinton era tax rates on households with incomes over $1 million. Actually the bill would restore Clinton era tax rates on households with incomes over $250,000.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling this to my attention.

The Washington Post is having trouble with numbers again. It told readers that the bill passed by the Senate in the summer would restore the Clinton era tax rates on households with incomes over $1 million. Actually the bill would restore Clinton era tax rates on households with incomes over $250,000.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling this to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

For some reason the media routinely bring up philosophy in discussions of politicians’ actions. This is utterly bizarre. There is no one in national office who got their position based on their philosophical treatises. They gained their positions by appealing to important political constituencies.

The NYT again committed this sin, telling readers in an article on the budget standoff that:

“The two sides are now dickering over price, not philosophical differences, and the numbers are very close.”

Does anyone think that President Obama and Speaker Boehner had been debating points of philosophy in their discussions?

This piece also raises the possibility that the government will use different inflation indexes for different programs in order to accomplish political ends telling readers:

“The new inflation calculations, for instance, would probably not affect wounded veterans and disabled people on Supplemental Security Income.”

This sort of political manipulation of government statistics is unusual in the United States. It would have been worth highlighting this part of the tentative agreement.

For some reason the media routinely bring up philosophy in discussions of politicians’ actions. This is utterly bizarre. There is no one in national office who got their position based on their philosophical treatises. They gained their positions by appealing to important political constituencies.

The NYT again committed this sin, telling readers in an article on the budget standoff that:

“The two sides are now dickering over price, not philosophical differences, and the numbers are very close.”

Does anyone think that President Obama and Speaker Boehner had been debating points of philosophy in their discussions?

This piece also raises the possibility that the government will use different inflation indexes for different programs in order to accomplish political ends telling readers:

“The new inflation calculations, for instance, would probably not affect wounded veterans and disabled people on Supplemental Security Income.”

This sort of political manipulation of government statistics is unusual in the United States. It would have been worth highlighting this part of the tentative agreement.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post can’t seem to run a simple budget piece without editorializing at every opportunity. Today it referred to the high income people who would be subject to higher tax rates under a new budget deal as “successful.” This assertion is only true if the criterion of success is being rich, in which case it would be more appropriate to simply refer to them as “rich.” Being successful and being rich may be synonymous to the Post’s editors, but that is not necessarily the view of the general population.

It also refers to the goal of reducing the projected deficit by $4 trillion over the next decade which it tells readers is:

“a target that economists say would stabilize the soaring federal debt.”

It should have been possible to write the sentence without the word “soaring.” (It would save space.) It’s also worth noting that more serious economists (the type who are able to notice $8 trillion housing bubbles) point out that a deal reached on taxes and spending over the next decade will not bind Congresses and presidents elected in 2016, 2018, 2020 and 2022.

Therefore this is mostly a big fight over writing words on paper in a context where we have little idea of the future. This is similar to the heated debates in the 2000 elections over the year when we would pay off the federal debt. Meanwhile, both Congress and the president are ignoring the wreckage from an economy in which close to 25 million people are unemployed, underemployed or out of the workforce altogether.

The Post can’t seem to run a simple budget piece without editorializing at every opportunity. Today it referred to the high income people who would be subject to higher tax rates under a new budget deal as “successful.” This assertion is only true if the criterion of success is being rich, in which case it would be more appropriate to simply refer to them as “rich.” Being successful and being rich may be synonymous to the Post’s editors, but that is not necessarily the view of the general population.

It also refers to the goal of reducing the projected deficit by $4 trillion over the next decade which it tells readers is:

“a target that economists say would stabilize the soaring federal debt.”

It should have been possible to write the sentence without the word “soaring.” (It would save space.) It’s also worth noting that more serious economists (the type who are able to notice $8 trillion housing bubbles) point out that a deal reached on taxes and spending over the next decade will not bind Congresses and presidents elected in 2016, 2018, 2020 and 2022.

Therefore this is mostly a big fight over writing words on paper in a context where we have little idea of the future. This is similar to the heated debates in the 2000 elections over the year when we would pay off the federal debt. Meanwhile, both Congress and the president are ignoring the wreckage from an economy in which close to 25 million people are unemployed, underemployed or out of the workforce altogether.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

For some reason the Washington Post has a hard time accurately reporting the nature of the budget discussions between President Obama and Speaker Boehner. It told readers today:

“In exchange for the higher rates for millionaires, Boehner is demanding changes to federal health and retirement programs, which are projected to be the biggest drivers of future federal borrowing.”

Of course Boehner is not looking for random “changes” to these programs, he is looking for “cuts” in the programs. While the next sentence points out that Boehner is seeking “savings” from these programs, there is no reason to obscure what is at issue by using “changes.”

It is also worth noting that under the law, Social Security cannot contribute to the deficit. It was set up by Congress as a stand alone program that can only spend money from its designated revenue stream. All official budget documents show the “on-budget” deficit which excludes revenue and spending from Social Security.

For some reason the Washington Post has a hard time accurately reporting the nature of the budget discussions between President Obama and Speaker Boehner. It told readers today:

“In exchange for the higher rates for millionaires, Boehner is demanding changes to federal health and retirement programs, which are projected to be the biggest drivers of future federal borrowing.”

Of course Boehner is not looking for random “changes” to these programs, he is looking for “cuts” in the programs. While the next sentence points out that Boehner is seeking “savings” from these programs, there is no reason to obscure what is at issue by using “changes.”

It is also worth noting that under the law, Social Security cannot contribute to the deficit. It was set up by Congress as a stand alone program that can only spend money from its designated revenue stream. All official budget documents show the “on-budget” deficit which excludes revenue and spending from Social Security.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Washington Post article on the state of the United Kingdom’s economy, after it followed the path of austerity advocated by deficit hawks, implied that consumer spending there has been depressed. This is not true.

While the saving rate has risen from the lows hit at the peak of the UK’s highest bubble, at 5.3 percent it is still well below the levels that the UK saw before the wealth created by its stock and housing bubbles began to drive consumption in the late 1990s. As is the case with the United States, the UK is likely to suffer from inadequate demand until its trade gets closer to balance.

This means that, rather than fearing foreign investors fleeing the British pound, the government should be encouraging such flight. A lower valued pound is the only way that the UK’s trade deficit can move substantially closer to balance. Without more balanced trade the economy will need large government budget deficits to sustain full employment.

A Washington Post article on the state of the United Kingdom’s economy, after it followed the path of austerity advocated by deficit hawks, implied that consumer spending there has been depressed. This is not true.

While the saving rate has risen from the lows hit at the peak of the UK’s highest bubble, at 5.3 percent it is still well below the levels that the UK saw before the wealth created by its stock and housing bubbles began to drive consumption in the late 1990s. As is the case with the United States, the UK is likely to suffer from inadequate demand until its trade gets closer to balance.

This means that, rather than fearing foreign investors fleeing the British pound, the government should be encouraging such flight. A lower valued pound is the only way that the UK’s trade deficit can move substantially closer to balance. Without more balanced trade the economy will need large government budget deficits to sustain full employment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s getting harder and harder to figure out what the Washington Post wants us to be worried about as the budget standoff approaches some sort of resolution. A front page Post article today warned readers that some tax increases and spending cuts are still likely to take effect on January 1, even if there is an agreement to extend the Bush tax cuts for the bottom 98 percent of households and to fix the alternative minimum tax and some other expiring provisions. The Post accurately points out that these residual tax increases and spending cuts will have the effect of slowing the economy.

However, the residual tax increases and spending cuts can also be called “deficit reduction” of the sort that the Post has been demanding to combat the deficits that have been causing it to hyperventilate for years. It was possible to point to many of the tax increases and spending cuts that were associated with the “cliff” as accidents that no one actually wanted to see go into effect, but the residual tax increases and spending cuts are likely to be there in large part by design.

While this will be bad news for an economy that desperately needs more stimulus (i.e. larger deficits), and also for the people directly affected, this is exactly the policy that the Post and other Washington establishment figures from both parties have been demanding. It would have been worth pointing out that the resulting hit to the economy is exactly what most advocates of deficit reduction presumably want if they understand the impact of the policies they advocate.

At one point this article tells readers:

“Hovering over these negotiations are reminders of the summer of 2011, when Obama and Boehner tried in vain to craft a “grand bargain” that would have saved $4 trillion in spending over the next decade and allowed an increase in the federal debt limit.”

This is not true. Obama and Boehner were never close to a deal that involved $4 trillion in spending cuts. They had set this $4 trillion figure as a target for deficit reduction, which would include spending cuts, tax increases and interest savings.

It’s getting harder and harder to figure out what the Washington Post wants us to be worried about as the budget standoff approaches some sort of resolution. A front page Post article today warned readers that some tax increases and spending cuts are still likely to take effect on January 1, even if there is an agreement to extend the Bush tax cuts for the bottom 98 percent of households and to fix the alternative minimum tax and some other expiring provisions. The Post accurately points out that these residual tax increases and spending cuts will have the effect of slowing the economy.

However, the residual tax increases and spending cuts can also be called “deficit reduction” of the sort that the Post has been demanding to combat the deficits that have been causing it to hyperventilate for years. It was possible to point to many of the tax increases and spending cuts that were associated with the “cliff” as accidents that no one actually wanted to see go into effect, but the residual tax increases and spending cuts are likely to be there in large part by design.

While this will be bad news for an economy that desperately needs more stimulus (i.e. larger deficits), and also for the people directly affected, this is exactly the policy that the Post and other Washington establishment figures from both parties have been demanding. It would have been worth pointing out that the resulting hit to the economy is exactly what most advocates of deficit reduction presumably want if they understand the impact of the policies they advocate.

At one point this article tells readers:

“Hovering over these negotiations are reminders of the summer of 2011, when Obama and Boehner tried in vain to craft a “grand bargain” that would have saved $4 trillion in spending over the next decade and allowed an increase in the federal debt limit.”

This is not true. Obama and Boehner were never close to a deal that involved $4 trillion in spending cuts. They had set this $4 trillion figure as a target for deficit reduction, which would include spending cuts, tax increases and interest savings.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has been an unofficial partner in the corporate sponsored Campaign to Fix the Debt’s efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare, devoting much of its news and opinion sections to advancing its agenda. This political position explains an article that examined the prospects for the U.S. economy after the budget impasse (a.k.a. the “fiscal cliff”) is resolved. The piece relied extensively on assertions from David M. Cote, a prominent deficit hawk and the CEO of Honeywell.

The piece quotes Cote:

“There is the possibility of a robust economic recovery if we are smart here. .?.?. If all of a sudden we can demonstrate that we can govern ourselves, we could affect the world.”

In this context it probably would have been worth mentioning that the interest rate on long-term Treasury bonds is just 1.7 percent. This fact suggests that most actors in financial markets do not share Mr. Cote’s concern about the ability of the United States to govern itself.

The piece relies further on Cote:

“He said the United States needs a tax-and-spending package of at least $4 trillion to be judged ‘credible’ by investors and trigger renewed growth. As head of Honeywell, he has frozen most hiring and capital investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal cliff — a strategy other corporate heads have followed as well to hedge against a new downturn.”

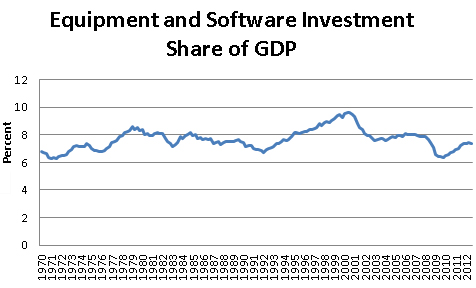

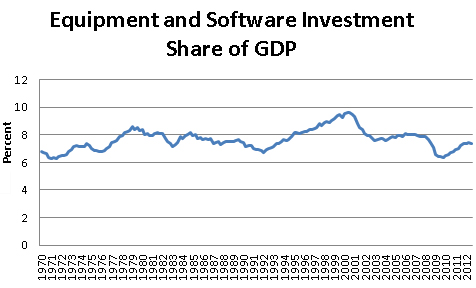

There is an easy way to evaluate this assertion. If what Cote is saying is true then we should be seeing unusually low levels of investment right now. In fact data from the Commerce Department show that, as a share of GDP, investment in equipment and software is only slightly below its pre-recession level. This is especially impressive given that large sectors of the economy are still operating well below their capacity.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

It is true that there has been some weakening of investment growth in the last half year or so, but even if investment returned to its growth rate in the first half of the year it would only have a modest impact on the pace of the recovery. In short, the data from the Commerce Department do not support what Mr. Cote is saying. If he in fact is delaying Honeywell investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal situation he is an exception among corporate decision makers.

This article also includes a bizarre comment in its discussion of the more rapid growth in the developing world in recent years, telling readers:

“But that could also sow the seeds of the next crisis if money floods into nations that are not equipped to manage it.”

The statement is of course true, but it is not clear what countries have demonstrated an ability to manage large inflows of money. Clearly the United States does not fit the bill.

Addendum:

A quick trip to Honeywell’s website indicates that the company does not appear to be putting its expansion plans on hold as Mr. Cote claimed. In the last two weeks it announced $20 million in new contracts to produce simulations for industrial companies, a new contract with Boeing, and the purchase of another company for $600 million.

The Washington Post has been an unofficial partner in the corporate sponsored Campaign to Fix the Debt’s efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare, devoting much of its news and opinion sections to advancing its agenda. This political position explains an article that examined the prospects for the U.S. economy after the budget impasse (a.k.a. the “fiscal cliff”) is resolved. The piece relied extensively on assertions from David M. Cote, a prominent deficit hawk and the CEO of Honeywell.

The piece quotes Cote:

“There is the possibility of a robust economic recovery if we are smart here. .?.?. If all of a sudden we can demonstrate that we can govern ourselves, we could affect the world.”

In this context it probably would have been worth mentioning that the interest rate on long-term Treasury bonds is just 1.7 percent. This fact suggests that most actors in financial markets do not share Mr. Cote’s concern about the ability of the United States to govern itself.

The piece relies further on Cote:

“He said the United States needs a tax-and-spending package of at least $4 trillion to be judged ‘credible’ by investors and trigger renewed growth. As head of Honeywell, he has frozen most hiring and capital investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal cliff — a strategy other corporate heads have followed as well to hedge against a new downturn.”

There is an easy way to evaluate this assertion. If what Cote is saying is true then we should be seeing unusually low levels of investment right now. In fact data from the Commerce Department show that, as a share of GDP, investment in equipment and software is only slightly below its pre-recession level. This is especially impressive given that large sectors of the economy are still operating well below their capacity.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

It is true that there has been some weakening of investment growth in the last half year or so, but even if investment returned to its growth rate in the first half of the year it would only have a modest impact on the pace of the recovery. In short, the data from the Commerce Department do not support what Mr. Cote is saying. If he in fact is delaying Honeywell investment because of uncertainty about the fiscal situation he is an exception among corporate decision makers.

This article also includes a bizarre comment in its discussion of the more rapid growth in the developing world in recent years, telling readers:

“But that could also sow the seeds of the next crisis if money floods into nations that are not equipped to manage it.”

The statement is of course true, but it is not clear what countries have demonstrated an ability to manage large inflows of money. Clearly the United States does not fit the bill.

Addendum:

A quick trip to Honeywell’s website indicates that the company does not appear to be putting its expansion plans on hold as Mr. Cote claimed. In the last two weeks it announced $20 million in new contracts to produce simulations for industrial companies, a new contract with Boeing, and the purchase of another company for $600 million.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión