The NYT had an interesting blog post on the increase in the number of jobs that require college degrees told readers that, “the wage gap between the typical college graduate and those who have completed no more than high school has been growing for the last few decades.”

This is somewhat misleading, as shown in the charts in the source linked to in the piece. The premium for people with just a college degree, compared to those without a college degree, has been almost flat for two decades. Almost all of the increase in the gap during this period has been due to wage growth for those with advanced degrees.

The NYT had an interesting blog post on the increase in the number of jobs that require college degrees told readers that, “the wage gap between the typical college graduate and those who have completed no more than high school has been growing for the last few decades.”

This is somewhat misleading, as shown in the charts in the source linked to in the piece. The premium for people with just a college degree, compared to those without a college degree, has been almost flat for two decades. Almost all of the increase in the gap during this period has been due to wage growth for those with advanced degrees.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s fascinating to read David Brooks’ column today. He boldly argues that Republicans:

“have to acknowledge how badly things are stacked against them. Polls show that large majorities of Americans are inclined to blame Republicans if the country goes off the ‘fiscal cliff.’ The business community, which needs a deal to boost confidence, will turn against them. The national security types and the defense contractors, who hate the prospect of sequestration, will turn against them.

“Moreover a budget stalemate on these terms will confirm every bad Republican stereotype. Republicans will be raising middle-class taxes in order to serve the rich — shafting Sam’s Club to benefit the country club. If Republicans do this, they might as well get Mitt Romney’s “47 percent” comments printed on T-shirts and wear them for the rest of their lives.”

Recognizing their weak position, he says that Republicans should be prepared to allow the top tax rate to rise to 36 or even 37 percent, but in exchange:

“Republicans should also ask for some medium-size entitlement cuts as part of the fiscal cliff down payment. These could fit within the framework Speaker John Boehner sketched out Monday afternoon: chaining Social Security cost-of-living increases to price inflation and increasing the Medicare Part B premium to 35 percent of costs.”

Excuse me, but what planet is David Brooks on? This would be comparable to Japan asking for Hawaii and parts of California as it was negotiating its surrender in World War II.

If nothing happens right now, the top tax rate goes to 39.6 percent on January 1, 2013. Let’s say that again just in case David Brooks is reading. If nothing happens right now, the top tax rate goes to 39.6 percent on January 1, 2013. There is nothing that John Boehner and the Republicans can do to stop this.

Furthermore, President Obama has a mandate to raise the top tax rate to 39.6 percent. Brooks probably missed this, but we just had a lengthy election campaign where taxes on the rich were the central issue. President Obama won.

Incredibly, Brooks’ proposal for “medium size entitlement cuts” would take a much bigger bite out of the income of retirees than his bold concessions on taxes would take out of the income of the rich. The cut to the cost of living adjustment would reduce lifetime benefits of seniors by around 3 percent. For the third of retirees that rely on Social Security for more than 90 percent of their income, this would be a cut in their income more than 2.5 percent.

In addition, Brooks wants to raise Medicare Part B premiums by 10 percentage points of the total cost from 25 percent to 35 percent. With the per person cost projected to average almost $6,000 a year over the next decade, this “medium size entitlement reform” would raise the cost to seniors by $600 a year. This is equal to 3 percent of the income of a senior with an income of $20,000, a figure that is somewhat higher than the median for people over the age of 65.

So Brooks is looking to cut the income net of Medicare expenses for the bottom half of Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries by almost 6 percent. And, his tax increases?

We don’t know exactly how Brooks would change the tax schedules, but let’s assume that the 35 percent bracket goes to 37 percent, Brooks’ higher number. And we’ll raise the 33 percent bracket to 35 percent. For a couple earning $500,000 a year, this would imply an increase in taxes of roughly $7,600 a year or 1.5 percent of their income.

So Brooks is proposing that as a starting offer (he wants bigger cuts on the table in the year ahead) moderate income seniors will see their income drop by 6 percent due to cuts in Social Security and Medicare, while the wealthy will see their income fall by 1.5 percent from tax increases. It’s interesting to think about what he would suggest putting on the table if the Republicans had won the election.

It’s fascinating to read David Brooks’ column today. He boldly argues that Republicans:

“have to acknowledge how badly things are stacked against them. Polls show that large majorities of Americans are inclined to blame Republicans if the country goes off the ‘fiscal cliff.’ The business community, which needs a deal to boost confidence, will turn against them. The national security types and the defense contractors, who hate the prospect of sequestration, will turn against them.

“Moreover a budget stalemate on these terms will confirm every bad Republican stereotype. Republicans will be raising middle-class taxes in order to serve the rich — shafting Sam’s Club to benefit the country club. If Republicans do this, they might as well get Mitt Romney’s “47 percent” comments printed on T-shirts and wear them for the rest of their lives.”

Recognizing their weak position, he says that Republicans should be prepared to allow the top tax rate to rise to 36 or even 37 percent, but in exchange:

“Republicans should also ask for some medium-size entitlement cuts as part of the fiscal cliff down payment. These could fit within the framework Speaker John Boehner sketched out Monday afternoon: chaining Social Security cost-of-living increases to price inflation and increasing the Medicare Part B premium to 35 percent of costs.”

Excuse me, but what planet is David Brooks on? This would be comparable to Japan asking for Hawaii and parts of California as it was negotiating its surrender in World War II.

If nothing happens right now, the top tax rate goes to 39.6 percent on January 1, 2013. Let’s say that again just in case David Brooks is reading. If nothing happens right now, the top tax rate goes to 39.6 percent on January 1, 2013. There is nothing that John Boehner and the Republicans can do to stop this.

Furthermore, President Obama has a mandate to raise the top tax rate to 39.6 percent. Brooks probably missed this, but we just had a lengthy election campaign where taxes on the rich were the central issue. President Obama won.

Incredibly, Brooks’ proposal for “medium size entitlement cuts” would take a much bigger bite out of the income of retirees than his bold concessions on taxes would take out of the income of the rich. The cut to the cost of living adjustment would reduce lifetime benefits of seniors by around 3 percent. For the third of retirees that rely on Social Security for more than 90 percent of their income, this would be a cut in their income more than 2.5 percent.

In addition, Brooks wants to raise Medicare Part B premiums by 10 percentage points of the total cost from 25 percent to 35 percent. With the per person cost projected to average almost $6,000 a year over the next decade, this “medium size entitlement reform” would raise the cost to seniors by $600 a year. This is equal to 3 percent of the income of a senior with an income of $20,000, a figure that is somewhat higher than the median for people over the age of 65.

So Brooks is looking to cut the income net of Medicare expenses for the bottom half of Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries by almost 6 percent. And, his tax increases?

We don’t know exactly how Brooks would change the tax schedules, but let’s assume that the 35 percent bracket goes to 37 percent, Brooks’ higher number. And we’ll raise the 33 percent bracket to 35 percent. For a couple earning $500,000 a year, this would imply an increase in taxes of roughly $7,600 a year or 1.5 percent of their income.

So Brooks is proposing that as a starting offer (he wants bigger cuts on the table in the year ahead) moderate income seniors will see their income drop by 6 percent due to cuts in Social Security and Medicare, while the wealthy will see their income fall by 1.5 percent from tax increases. It’s interesting to think about what he would suggest putting on the table if the Republicans had won the election.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

While it apparently is news to the Washington Post, those who follow politics realize that politicians are not always completely honest in their public statements. That is why it is important never to take what they say entirely face value.

For this reason the Washington Post erred when it reported in a front page story that:

“Republicans were outraged by the president’s proposal [on the budget], calling it a step backward.”

In fact, the Post has no way of knowing whether the Republicans were in fact outraged. It of course helps the Republican’s position enormously to imply that President Obama’s proposal was in fact outrageous. The Post simply should have reported the Republicans claim that they were outraged (e.g. “Republicans claimed to have been outraged by the president’s proposal).

The piece then continues its reporting from the Republican perspective:

“On Monday, Boehner referred to it as the president’s ‘la-la-land offer.’

‘We could have responded in kind, but we decided not to do that,’ Boehner told reporters.

“Instead, Boehner began last week rallying top Republicans around the Bowles framework, which was presented in November 2011 to a special deficit- reduction “supercommittee” of Congress.”

The Post’s discussion implies the Boehner responded to President Obama’s proposal with a compromise position that was reasonable, in contrast to the unreasonable proposal that the president had put on the table. This sort of editorializing is supposed to be left to the opinion sections.

While it apparently is news to the Washington Post, those who follow politics realize that politicians are not always completely honest in their public statements. That is why it is important never to take what they say entirely face value.

For this reason the Washington Post erred when it reported in a front page story that:

“Republicans were outraged by the president’s proposal [on the budget], calling it a step backward.”

In fact, the Post has no way of knowing whether the Republicans were in fact outraged. It of course helps the Republican’s position enormously to imply that President Obama’s proposal was in fact outrageous. The Post simply should have reported the Republicans claim that they were outraged (e.g. “Republicans claimed to have been outraged by the president’s proposal).

The piece then continues its reporting from the Republican perspective:

“On Monday, Boehner referred to it as the president’s ‘la-la-land offer.’

‘We could have responded in kind, but we decided not to do that,’ Boehner told reporters.

“Instead, Boehner began last week rallying top Republicans around the Bowles framework, which was presented in November 2011 to a special deficit- reduction “supercommittee” of Congress.”

The Post’s discussion implies the Boehner responded to President Obama’s proposal with a compromise position that was reasonable, in contrast to the unreasonable proposal that the president had put on the table. This sort of editorializing is supposed to be left to the opinion sections.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post, along with the other Serious People in Washington, is engaged in a full court press to cut Social Security and Medicare. It is prepared to use all the resources of the newspaper to accomplish this end, even if this means ignoring normal journalistic standards.

This explains its front page attack on AARP over its opposition to cuts to Medicare and Social Security. The piece tells readers that AARP, because of its marketing of Medigap insurance, has a conflict of interest in this debate. The argument is that if the age of eligibility for Medicare is raised from 65 to 67, fewer people would qualify for Medicare and therefore fewer people would be able to purchase AARP’s Medigap insurance.

The idea that this presents a conflict of interest for an organization that first and foremost is supposed to be committed to protecting the interest of older people is absurd on its face. Polls consistently show that raising the age of eligibility for Medicare is enormously unpopular. It is especially unpopular for the age groups that comprise AARP’s membership. This is clearly a phony scandal concocted by the Post to punish AARP for opposing its efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare.

It is striking that the financial interests of others involved in this debate are never mentioned in news stories. For example, the Post never mentions that Erskine Bowles has received hundreds of thousands of dollars as a director of Morgan Stanley, the Wall Street investment bank. This could help to explain why proposals to impose a financial speculation tax have never been included in any of the deficit reduction packages that he has put forward.

The Washington Post, along with the other Serious People in Washington, is engaged in a full court press to cut Social Security and Medicare. It is prepared to use all the resources of the newspaper to accomplish this end, even if this means ignoring normal journalistic standards.

This explains its front page attack on AARP over its opposition to cuts to Medicare and Social Security. The piece tells readers that AARP, because of its marketing of Medigap insurance, has a conflict of interest in this debate. The argument is that if the age of eligibility for Medicare is raised from 65 to 67, fewer people would qualify for Medicare and therefore fewer people would be able to purchase AARP’s Medigap insurance.

The idea that this presents a conflict of interest for an organization that first and foremost is supposed to be committed to protecting the interest of older people is absurd on its face. Polls consistently show that raising the age of eligibility for Medicare is enormously unpopular. It is especially unpopular for the age groups that comprise AARP’s membership. This is clearly a phony scandal concocted by the Post to punish AARP for opposing its efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare.

It is striking that the financial interests of others involved in this debate are never mentioned in news stories. For example, the Post never mentions that Erskine Bowles has received hundreds of thousands of dollars as a director of Morgan Stanley, the Wall Street investment bank. This could help to explain why proposals to impose a financial speculation tax have never been included in any of the deficit reduction packages that he has put forward.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

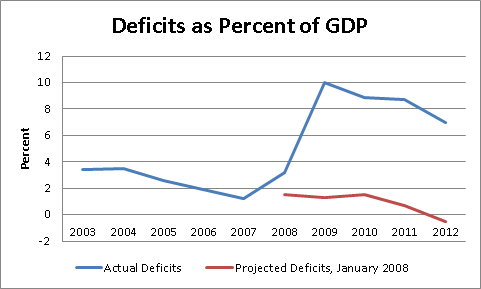

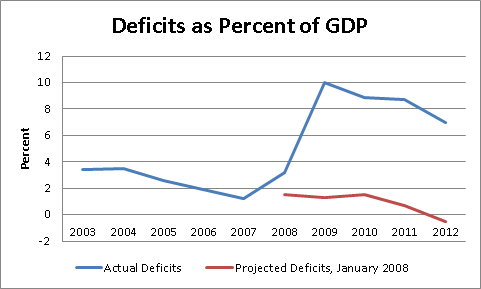

Paul Krugman’s columns and blogs are a great source of insight on the economy and the budget, but he does occasionally make mistakes. He is guilty of one today, when he used a very misleading graph on the sources of the budget deficits in his blog.

There are two major problems with the graph. First, it begins in 2009. This might lead readers to believe that large budget deficits had been an ongoing problem. That is not true. The deficit was just 1.2 percent of GDP in 2007 and was projected to remain low until the collapse of the housing market sent the economy plummeting in 2008.

The other problem is that it shows the deficit in nominal dollars rather than as a share of GDP. This conceals the fact that the deficit was projected to be about half as large as a share of GDP in 2019 as it was in 2009. While the deficit projected for 2019 would still be too large to sustain indefinitely, by not expressing the deficit relative to the size of the economy, readers are likely to exaggerate the extent of the problem it would pose.

A graph that gives a better picture of the problem of the budget deficit in relation to the economy would look like the one below. The point is that the collapse of the economy gave us large deficits. Even with the wars and the Bush tax cuts to the rich, the deficits would still have been manageable had the economy not collapsed.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Paul Krugman’s columns and blogs are a great source of insight on the economy and the budget, but he does occasionally make mistakes. He is guilty of one today, when he used a very misleading graph on the sources of the budget deficits in his blog.

There are two major problems with the graph. First, it begins in 2009. This might lead readers to believe that large budget deficits had been an ongoing problem. That is not true. The deficit was just 1.2 percent of GDP in 2007 and was projected to remain low until the collapse of the housing market sent the economy plummeting in 2008.

The other problem is that it shows the deficit in nominal dollars rather than as a share of GDP. This conceals the fact that the deficit was projected to be about half as large as a share of GDP in 2019 as it was in 2009. While the deficit projected for 2019 would still be too large to sustain indefinitely, by not expressing the deficit relative to the size of the economy, readers are likely to exaggerate the extent of the problem it would pose.

A graph that gives a better picture of the problem of the budget deficit in relation to the economy would look like the one below. The point is that the collapse of the economy gave us large deficits. Even with the wars and the Bush tax cuts to the rich, the deficits would still have been manageable had the economy not collapsed.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane is angry with Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve Board. He is upset because the Fed is not working to advance his agenda of cutting Social Security and Medicare by raising interest rates and putting more pressure on Congress.

Lane tells readers:

“With the U.S. economy still reeling from the Great Recession, the Fed has been trying to stimulate economic growth by holding down interest rates, and it has pledged to keep doing so through mid-2015. It does this in large part by buying up government debt. Partly as a result, the United States was able to issue $4 trillion in new debt from 2009 through 2011, while keeping net interest costs at or below 1.5 percent of gross domestic product.

“It’s perfectly consistent with the Fed’s mandate. And it sounds like a great deal for the government, too. According to more than a few economists, pundits and politicians, Congress should seize the opportunity to borrow and spend on growth-enhancing investments such as infrastructure.

“However, in a properly functioning economy, rising government borrowing costs can play a useful role: Specifically, they are the market’s way of warning government that its debts are unsustainable.

Muffle that signal, as the Fed’s policy is doing now, and politicians are less able to guess right about how much time they really have to fix fiscal policy and to feel less pressure to do so.”

Actually the market is doing exactly what it is supposed to be doing. Interest rates are extraordinarily low now because of the massive amount of excess resources in the economy. The low interest rates are a way to encourage spending. In fact, if anything the goal would be to have lower real interest rates, but this can only be done by having a higher rate of inflation.

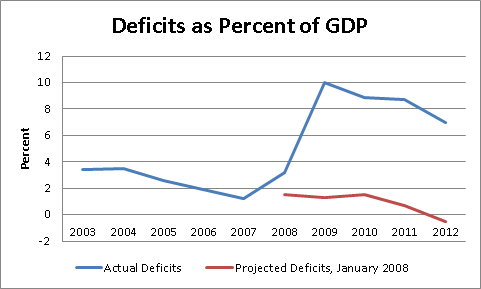

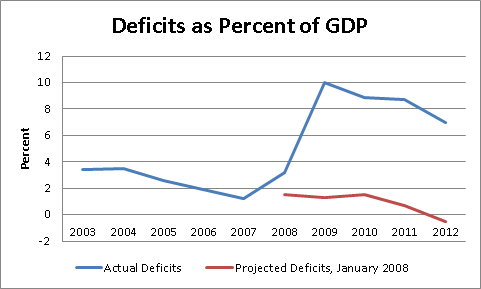

Lane is upset that the markets don’t seem to accept his view that budget deficits are unsustainable. Of course the only reason that budget deficits are large today is because the economy collapsed. In 2008, before it recognized the hit to the economy caused by the collapse of the housing bubble, the Congressional Budget Office projected that deficits would be less than 2.0 percent of GDP through the middle of the decade even without the expiration of the Bush tax cuts.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

In short, the real story here is that Charles Lane is unhappy that the financial markets and the Fed won’t join in his drive to cut Social Security and Medicare.

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane is angry with Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve Board. He is upset because the Fed is not working to advance his agenda of cutting Social Security and Medicare by raising interest rates and putting more pressure on Congress.

Lane tells readers:

“With the U.S. economy still reeling from the Great Recession, the Fed has been trying to stimulate economic growth by holding down interest rates, and it has pledged to keep doing so through mid-2015. It does this in large part by buying up government debt. Partly as a result, the United States was able to issue $4 trillion in new debt from 2009 through 2011, while keeping net interest costs at or below 1.5 percent of gross domestic product.

“It’s perfectly consistent with the Fed’s mandate. And it sounds like a great deal for the government, too. According to more than a few economists, pundits and politicians, Congress should seize the opportunity to borrow and spend on growth-enhancing investments such as infrastructure.

“However, in a properly functioning economy, rising government borrowing costs can play a useful role: Specifically, they are the market’s way of warning government that its debts are unsustainable.

Muffle that signal, as the Fed’s policy is doing now, and politicians are less able to guess right about how much time they really have to fix fiscal policy and to feel less pressure to do so.”

Actually the market is doing exactly what it is supposed to be doing. Interest rates are extraordinarily low now because of the massive amount of excess resources in the economy. The low interest rates are a way to encourage spending. In fact, if anything the goal would be to have lower real interest rates, but this can only be done by having a higher rate of inflation.

Lane is upset that the markets don’t seem to accept his view that budget deficits are unsustainable. Of course the only reason that budget deficits are large today is because the economy collapsed. In 2008, before it recognized the hit to the economy caused by the collapse of the housing bubble, the Congressional Budget Office projected that deficits would be less than 2.0 percent of GDP through the middle of the decade even without the expiration of the Bush tax cuts.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

In short, the real story here is that Charles Lane is unhappy that the financial markets and the Fed won’t join in his drive to cut Social Security and Medicare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Europe has an enormous problem of youth unemployment, this is not really disputable. The NYT ran a major article on the topic that focused on the situation in France. It told readers:

“This is a ‘floating generation,’ made worse by the euro crisis, and its plight is widely seen as a failure of the system: an elitist educational tradition that does not integrate graduates into the work force, a rigid labor market that is hard to enter, and a tax system that makes it expensive for companies to hire full-time employees and both difficult and expensive to lay them off.”

When facts about the world are “widely seen,” readers should get nervous. People see these facts, we want names.

The point is a serious one. This piece highlights the problems of the education system in France and other countries and blames them for high youth unemployment and underemployment. While there are undoubtedly serious problems with these educational systems (as with most systems), these problems did not suddenly get much worse in the last 5 years. The reason for the scary youth employment/unemployment data cited in this piece is the economic collapse in 2008 and the decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) to push austerity as a response. The policies of the ECB bear far more responsibility for the dire state of the labor market for youth in France and the rest of Europe than problems with the education system.

It is also worth noting that the French unemployment data tend to overstate youth unemployment. College students are given stipends, so most do not work, unlike in the United States. Therefore the youth labor force is much smaller in France. This means that if the same share of youth are unemployed it would translate into a much higher unemployment rate in France.

Europe has an enormous problem of youth unemployment, this is not really disputable. The NYT ran a major article on the topic that focused on the situation in France. It told readers:

“This is a ‘floating generation,’ made worse by the euro crisis, and its plight is widely seen as a failure of the system: an elitist educational tradition that does not integrate graduates into the work force, a rigid labor market that is hard to enter, and a tax system that makes it expensive for companies to hire full-time employees and both difficult and expensive to lay them off.”

When facts about the world are “widely seen,” readers should get nervous. People see these facts, we want names.

The point is a serious one. This piece highlights the problems of the education system in France and other countries and blames them for high youth unemployment and underemployment. While there are undoubtedly serious problems with these educational systems (as with most systems), these problems did not suddenly get much worse in the last 5 years. The reason for the scary youth employment/unemployment data cited in this piece is the economic collapse in 2008 and the decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) to push austerity as a response. The policies of the ECB bear far more responsibility for the dire state of the labor market for youth in France and the rest of Europe than problems with the education system.

It is also worth noting that the French unemployment data tend to overstate youth unemployment. College students are given stipends, so most do not work, unlike in the United States. Therefore the youth labor force is much smaller in France. This means that if the same share of youth are unemployed it would translate into a much higher unemployment rate in France.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an excellent piece detailing the process whereby corporate subsidies are dished out in Texas. It reports that the subsidies come to around $19 billion a year. This is approximately $2,200 per household. As the piece points out, the incentives have been handed out with little apparent regard to the number or quality of jobs created. As a result, there is little evidence that the incentives have had benefits for most Texans.

The piece is part of a series on state subsidies for corporations. The first piece ran yesterday.

The NYT had an excellent piece detailing the process whereby corporate subsidies are dished out in Texas. It reports that the subsidies come to around $19 billion a year. This is approximately $2,200 per household. As the piece points out, the incentives have been handed out with little apparent regard to the number or quality of jobs created. As a result, there is little evidence that the incentives have had benefits for most Texans.

The piece is part of a series on state subsidies for corporations. The first piece ran yesterday.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post neglected to point out that Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican often cited on budget issues, is apparently badly confused about the basics of the budget. A Post piece quoted Graham as saying:

“This offer doesn’t remotely deal with entitlement reform in a way to save Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security from imminent bankruptcy.”

This statement is absurd on its face. Medicaid is paid out of general revenue, it makes no more sense to say that Medicaid faces bankruptcy than to say that the Commerce Department faces bankruptcy. While the same is true of Medicare Part B and Part D, the Hospital Insurance portion of the program (Part A) is funded by a trust fund with a designated revenue source that is first projected to face a shortfall in 2024. If the projections prove correct, at that point it would lack sufficient revenue to pay full benefits.

While this would be a problem, it is worth noting that, contrary to the criticisms made by Graham in the piece, President Obama’s reforms have extended the projected solvency of the program from 2016 to 2024. They have also eliminated more than two-thirds of the projected 75-year shortfall.

In the case of Social Security, the projections from the Congressional Budget Office show that the program can pay all scheduled benefits through the year 2035 with no changes whatsoever. Even after that date it would be able to pay close to 80 percent of scheduled benefits for the rest of the century, leaving future beneficiaries with benefits that considerably exceed those of current retirees.

The Post should have pointed out that what Graham asserted was nonsense, since many readers may not have recognized this fact. Actually, this astounding gaffe should have been the focus of the piece, since Graham is often treated by the media as an expert on the budget. It is probably worth noting that Graham typically presents views on the budget that are similar to the Post’s editors.

The Post neglected to point out that Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican often cited on budget issues, is apparently badly confused about the basics of the budget. A Post piece quoted Graham as saying:

“This offer doesn’t remotely deal with entitlement reform in a way to save Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security from imminent bankruptcy.”

This statement is absurd on its face. Medicaid is paid out of general revenue, it makes no more sense to say that Medicaid faces bankruptcy than to say that the Commerce Department faces bankruptcy. While the same is true of Medicare Part B and Part D, the Hospital Insurance portion of the program (Part A) is funded by a trust fund with a designated revenue source that is first projected to face a shortfall in 2024. If the projections prove correct, at that point it would lack sufficient revenue to pay full benefits.

While this would be a problem, it is worth noting that, contrary to the criticisms made by Graham in the piece, President Obama’s reforms have extended the projected solvency of the program from 2016 to 2024. They have also eliminated more than two-thirds of the projected 75-year shortfall.

In the case of Social Security, the projections from the Congressional Budget Office show that the program can pay all scheduled benefits through the year 2035 with no changes whatsoever. Even after that date it would be able to pay close to 80 percent of scheduled benefits for the rest of the century, leaving future beneficiaries with benefits that considerably exceed those of current retirees.

The Post should have pointed out that what Graham asserted was nonsense, since many readers may not have recognized this fact. Actually, this astounding gaffe should have been the focus of the piece, since Graham is often treated by the media as an expert on the budget. It is probably worth noting that Graham typically presents views on the budget that are similar to the Post’s editors.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión