It seems that many people have been bothered by a Wall Street Journal column co-authored by Chris Cox and Bill Archer, the former Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. The column warns of an $86 trillion dollar deficit if we propoerly account for the liabilities of Social Security, Medicare and other government obligations. That’s scary.

Fortunately, we have been around the block with this argument before. If we go to the CEPR’s oldies section we find this 2003 classic on the $44 trillion deficit scare. The story’s the same, even if the numbers have been changed somewhat.

It seems that many people have been bothered by a Wall Street Journal column co-authored by Chris Cox and Bill Archer, the former Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. The column warns of an $86 trillion dollar deficit if we propoerly account for the liabilities of Social Security, Medicare and other government obligations. That’s scary.

Fortunately, we have been around the block with this argument before. If we go to the CEPR’s oldies section we find this 2003 classic on the $44 trillion deficit scare. The story’s the same, even if the numbers have been changed somewhat.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Both the NYT and Washington Post reported on a tax proposal from Republicans which could lead to a large tax increase on the slightly rich, while leaving the very rich little affected. The proposal would have the lower tax brackets (e.g. the 10 percent rate on the first $20,000 of income and the 15 percent rate on income between $20,000 and $70,000) phased out for households with incomes above $250,000.

Remarkably, neither paper pointed out to readers that this proposal would imply a substantial increase in marginal tax rates for those in income range where these lower tax rates were being phased out. This omission was striking both because of the policy and political implications of the proposal.

On the policy side it would mean that most of the people seeing higher tax rates would be subject to a higher marginal tax rate. (The phase out of the lower brackets is the same thing as a higher marginal tax rate.) While neither article mentioned the range over which the phase out would occur, the vast majority of the people over the $250,000 threshold earn an amount near this threshold. This means that if the phase out ended at $750,000, or even $500,000, most of the people facing tax increases would be in the bubble range facing the higher marginal tax rate.

Insofar as we are concerned about the disincentive of higher marginal tax rates, we should want to see as few people as possible subject to higher rates. This policy would cause a large number of the slightly wealthy to face a higher marginal tax rate.

The politics of this proposal are even more striking. The Republicans had highlighted the fate of small business owners who they like to call “job creators.” This policy would imply a higher tax rate on the vast majority of the job creators, while leaving the very rich little affected, since their income would place them well above the bubble cutoff. This proposal would seem to imply that the Republicans were willing to nail the job creators to benefit the very wealthy.

Readers of the NYT and Post might have missed this basic fact, but fortunately Nate Silver came to the rescue. He carefully explained the basic story to readers in his blog this morning.

Both the NYT and Washington Post reported on a tax proposal from Republicans which could lead to a large tax increase on the slightly rich, while leaving the very rich little affected. The proposal would have the lower tax brackets (e.g. the 10 percent rate on the first $20,000 of income and the 15 percent rate on income between $20,000 and $70,000) phased out for households with incomes above $250,000.

Remarkably, neither paper pointed out to readers that this proposal would imply a substantial increase in marginal tax rates for those in income range where these lower tax rates were being phased out. This omission was striking both because of the policy and political implications of the proposal.

On the policy side it would mean that most of the people seeing higher tax rates would be subject to a higher marginal tax rate. (The phase out of the lower brackets is the same thing as a higher marginal tax rate.) While neither article mentioned the range over which the phase out would occur, the vast majority of the people over the $250,000 threshold earn an amount near this threshold. This means that if the phase out ended at $750,000, or even $500,000, most of the people facing tax increases would be in the bubble range facing the higher marginal tax rate.

Insofar as we are concerned about the disincentive of higher marginal tax rates, we should want to see as few people as possible subject to higher rates. This policy would cause a large number of the slightly wealthy to face a higher marginal tax rate.

The politics of this proposal are even more striking. The Republicans had highlighted the fate of small business owners who they like to call “job creators.” This policy would imply a higher tax rate on the vast majority of the job creators, while leaving the very rich little affected, since their income would place them well above the bubble cutoff. This proposal would seem to imply that the Republicans were willing to nail the job creators to benefit the very wealthy.

Readers of the NYT and Post might have missed this basic fact, but fortunately Nate Silver came to the rescue. He carefully explained the basic story to readers in his blog this morning.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Folks who have been awake during the last six months recall that the Republicans opposed raising marginal tax rates on the wealthy as the highest principle of politics and economics. That is why it should have been a huge news story when they proposed a plan that would do exactly this, but only for the less wealthy who fall in that esteemed group they call “job creators.” Remarkably the Post article that reported on this change totally ignored this break with Republican theology.

The break comes in the form of what the Post describes as a “bubble tax” which it claims that Republicans are proposing. The bubble tax would phase out the lower tax brackets (e.g. the 10 percent tax bracket for income under $17,900 and the 15 percent bracket for income between $17,900 and $72,500). This phase out implies an increase in the marginal tax rate over the period of the phase out. For example, if the phase out for couples occurs between the income range of $250,000 and $750,000 it would be roughly equivalent to an increase of 5 percentage points in the marginal tax rate over this income interval. That would actually be a larger increase in the marginal tax rate for people in this income range than just letting the Bush tax cuts expire. (Of course the phase out could be more gradual, but then it would raise less money.)

The income levels that would be most affected by this sort of restructuring of the tax code includes the overwhelming majority of small business owners who the Republicans have blessed as “the job creators.” Given this change in positions by the Republicans, it might have been appropriate to headline this piece something like:

“Republicans throw “job creators” under the bus to limit taxes for the very rich.”

The article also refers to a proposal by Senator Susan Collins that would raise taxes on people earning more than $1 million, except for those who own a small business. It would have been worth pointing out to readers that this small business exemption would essentially make the tax increase optional for the very rich. It is unlikely that there are many people in this income category who either could not figure out how to make themselves a small business owner or hire an accountant to pull off this trick.

In keeping with the Post’s longstanding editorial policy of pushing for cuts in Social Security the third paragraph of the piece referred to the:

“skyrocketing cost of federal retirement programs such as Social Security and Medicare.”

Of course Social Security costs are not skyrocketing by most definitions of the term, with spending as a share of GDP projected to increase from 5 percent to 6 percent over the next two decades. Medicare costs are rising more rapidly, but this is due to projections that show U.S. health care costs in general rising rapidly.

The piece also used the term “fiscal cliff” in both the headline and first paragraph. This term, which is not an accurate description of the impact of the expiration of the tax cuts and the spending sequester that takes place in January, helps to imply an atmosphere of crisis over not reaching a budget deal by January 1. This also fits the Post’s agenda of pushing for a deal this year that is likely to be on more favorable terms to the Republicans than a deal that is made after the tax cuts expire.

Folks who have been awake during the last six months recall that the Republicans opposed raising marginal tax rates on the wealthy as the highest principle of politics and economics. That is why it should have been a huge news story when they proposed a plan that would do exactly this, but only for the less wealthy who fall in that esteemed group they call “job creators.” Remarkably the Post article that reported on this change totally ignored this break with Republican theology.

The break comes in the form of what the Post describes as a “bubble tax” which it claims that Republicans are proposing. The bubble tax would phase out the lower tax brackets (e.g. the 10 percent tax bracket for income under $17,900 and the 15 percent bracket for income between $17,900 and $72,500). This phase out implies an increase in the marginal tax rate over the period of the phase out. For example, if the phase out for couples occurs between the income range of $250,000 and $750,000 it would be roughly equivalent to an increase of 5 percentage points in the marginal tax rate over this income interval. That would actually be a larger increase in the marginal tax rate for people in this income range than just letting the Bush tax cuts expire. (Of course the phase out could be more gradual, but then it would raise less money.)

The income levels that would be most affected by this sort of restructuring of the tax code includes the overwhelming majority of small business owners who the Republicans have blessed as “the job creators.” Given this change in positions by the Republicans, it might have been appropriate to headline this piece something like:

“Republicans throw “job creators” under the bus to limit taxes for the very rich.”

The article also refers to a proposal by Senator Susan Collins that would raise taxes on people earning more than $1 million, except for those who own a small business. It would have been worth pointing out to readers that this small business exemption would essentially make the tax increase optional for the very rich. It is unlikely that there are many people in this income category who either could not figure out how to make themselves a small business owner or hire an accountant to pull off this trick.

In keeping with the Post’s longstanding editorial policy of pushing for cuts in Social Security the third paragraph of the piece referred to the:

“skyrocketing cost of federal retirement programs such as Social Security and Medicare.”

Of course Social Security costs are not skyrocketing by most definitions of the term, with spending as a share of GDP projected to increase from 5 percent to 6 percent over the next two decades. Medicare costs are rising more rapidly, but this is due to projections that show U.S. health care costs in general rising rapidly.

The piece also used the term “fiscal cliff” in both the headline and first paragraph. This term, which is not an accurate description of the impact of the expiration of the tax cuts and the spending sequester that takes place in January, helps to imply an atmosphere of crisis over not reaching a budget deal by January 1. This also fits the Post’s agenda of pushing for a deal this year that is likely to be on more favorable terms to the Republicans than a deal that is made after the tax cuts expire.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson is again perplexed by the failure of the economy to recover more rapidly. It is difficult for those of us who understand national income accounting (the stuff we teach in intro econ) to understand the confusion.

Prior to the economic collapse the economy was being driven by a housing bubble. When the bubble burst, we lost more than $600 billion in annual construction demand and more than $500 billion in annual consumption demand. There is no obvious mechanism in the economy to replace this demand.

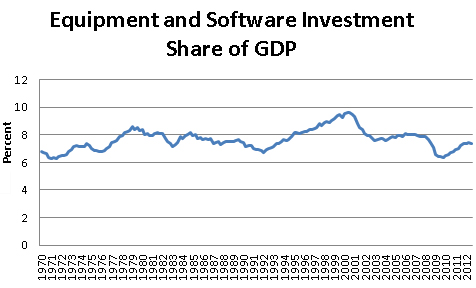

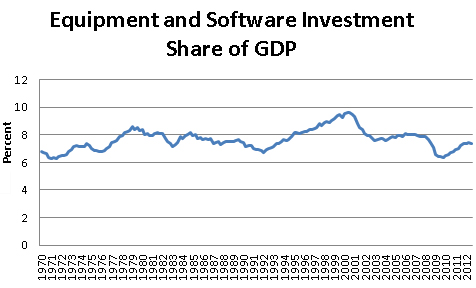

Samuelson tells us that companies are cautious and reluctant to invest due to the uncertain state of the economy. However the equipment and software share of investment is pretty much back to its pre-recession level. It’s not clear why we should expect the share to rise higher, especially at a time when there is so much excess capacity in many sectors.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

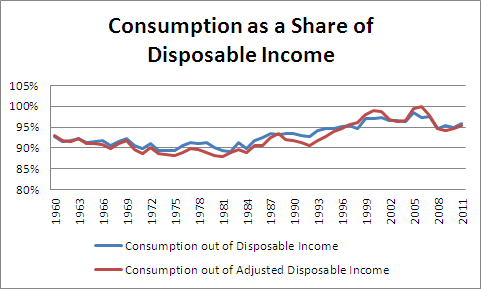

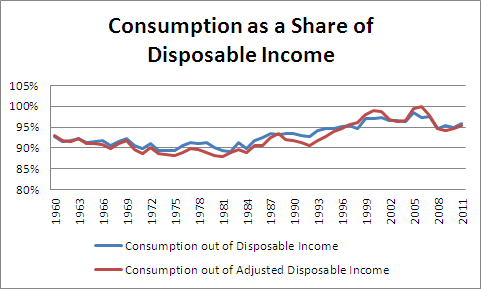

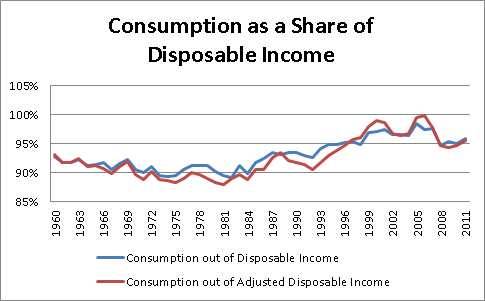

Consumption is also unusually high relative to disposable income, although below its bubble peak. This drop is also not surprising given the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Samuelson also expresses surprise that there has not been more of a rebound in housing, telling readers:

“The Fed’s low interest rates and plunging home prices (down about a third nationally) might have triggered a strong housing revival.”

Of course given that vacancy rates remain close to the record highs hit earlier in the downturn, it is not surprising that construction has not been stronger.

If more people engaged in policy debates learned national income accounting it would eliminate much of the confusion that dominates debates.

Robert Samuelson is again perplexed by the failure of the economy to recover more rapidly. It is difficult for those of us who understand national income accounting (the stuff we teach in intro econ) to understand the confusion.

Prior to the economic collapse the economy was being driven by a housing bubble. When the bubble burst, we lost more than $600 billion in annual construction demand and more than $500 billion in annual consumption demand. There is no obvious mechanism in the economy to replace this demand.

Samuelson tells us that companies are cautious and reluctant to invest due to the uncertain state of the economy. However the equipment and software share of investment is pretty much back to its pre-recession level. It’s not clear why we should expect the share to rise higher, especially at a time when there is so much excess capacity in many sectors.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Consumption is also unusually high relative to disposable income, although below its bubble peak. This drop is also not surprising given the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Samuelson also expresses surprise that there has not been more of a rebound in housing, telling readers:

“The Fed’s low interest rates and plunging home prices (down about a third nationally) might have triggered a strong housing revival.”

Of course given that vacancy rates remain close to the record highs hit earlier in the downturn, it is not surprising that construction has not been stronger.

If more people engaged in policy debates learned national income accounting it would eliminate much of the confusion that dominates debates.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It seems to really pain the Washington Post editors that retirees can collect Social Security checks that average just over $1,200 a month. The amount of ink that they have devoted in both their opinion and news pages to cutting benefits could probably fill the Great Lakes. They’re at it again today pushing a cut in the annual cost of living adjustment by adopting a chained CPI as the measure of inflation.

As expected, the piece uses more than a bit of sleight of hand to make its case. For example, it tells readers:

“Economists have developed a more realistic measure of inflation, known for obscure reasons as the “chained CPI” (consumer price index), which has averaged a little under 0.3 percentage points less per year than existing measures.”

Actually, economists do not know if this index is a more realistic measure of the rate of inflation experienced by the elderly. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has constructed an experimental elderly index that has typically shown a rate of inflation that is roughly 0.3 percentage points higher than the standard measure of inflation.

This is just an experimental index and it is not “chained,” which means that it does not pick up the effects of substitution among items by the elderly, however if the Post’s concern is to have a “more realistic” measure of inflation then it would join the call of more than 250 economists for having BLS construct a full chained CPI.

This index may end up showing a higher or lower rate of inflation than the current index, but it would give us a better measure of the inflation rate experienced by the elderly. Congress’ intent in establishing the cost of living adjustment in the first place was to have benefits keep pace with inflation. An elderly CPI would do that, switching to a chained CPI is simply an underhanded way to cut benefits.

The Post also tells us:

“Adjusting those annual increments merely reduces the rate of growth in seniors’ benefits; it does not actually cut them.”

Yes, save this one for the Post’s Kids section. The cut reduces the real value of benefits. This is not an argument for adults.

It then adds:

“The immediate impact is negligible — just $1 billion in the first year. That gives future retirees time to adjust.”

Huh? Did anyone say that the cut in benefits would only apply to future retirees?

Once again the Post wants to cut Social Security benefits but does not have the courage to be honest about what it’s proposing. It must really bother them that workers can get $1,200 a month in retirement.

It seems to really pain the Washington Post editors that retirees can collect Social Security checks that average just over $1,200 a month. The amount of ink that they have devoted in both their opinion and news pages to cutting benefits could probably fill the Great Lakes. They’re at it again today pushing a cut in the annual cost of living adjustment by adopting a chained CPI as the measure of inflation.

As expected, the piece uses more than a bit of sleight of hand to make its case. For example, it tells readers:

“Economists have developed a more realistic measure of inflation, known for obscure reasons as the “chained CPI” (consumer price index), which has averaged a little under 0.3 percentage points less per year than existing measures.”

Actually, economists do not know if this index is a more realistic measure of the rate of inflation experienced by the elderly. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has constructed an experimental elderly index that has typically shown a rate of inflation that is roughly 0.3 percentage points higher than the standard measure of inflation.

This is just an experimental index and it is not “chained,” which means that it does not pick up the effects of substitution among items by the elderly, however if the Post’s concern is to have a “more realistic” measure of inflation then it would join the call of more than 250 economists for having BLS construct a full chained CPI.

This index may end up showing a higher or lower rate of inflation than the current index, but it would give us a better measure of the inflation rate experienced by the elderly. Congress’ intent in establishing the cost of living adjustment in the first place was to have benefits keep pace with inflation. An elderly CPI would do that, switching to a chained CPI is simply an underhanded way to cut benefits.

The Post also tells us:

“Adjusting those annual increments merely reduces the rate of growth in seniors’ benefits; it does not actually cut them.”

Yes, save this one for the Post’s Kids section. The cut reduces the real value of benefits. This is not an argument for adults.

It then adds:

“The immediate impact is negligible — just $1 billion in the first year. That gives future retirees time to adjust.”

Huh? Did anyone say that the cut in benefits would only apply to future retirees?

Once again the Post wants to cut Social Security benefits but does not have the courage to be honest about what it’s proposing. It must really bother them that workers can get $1,200 a month in retirement.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ross Douthat argues convincingly that if we eliminated the link between contributions and benefits it would be much easier politically to cut Social Security. Of course he thinks ending the link would be a good idea for that reason, but his logic is certainly on the mark, people will more strongly protect benefits that they feel they have earned.

Douthat is off on a few other points. He tells readers:

“In an era of mass unemployment, mediocre wage growth and weak mobility from the bottom of the income ladder, it makes no sense to finance our retirement system with a tax that falls directly on wages and hiring and imposes particular burdens on small business and the working class.

“What’s more, the payroll tax as it exists today can’t cover the program’s projected liabilities anyway, and the pay-as-you-go myth stands in the way of the changes required to keep Social Security solvent.”

The problem here is that we are not condemned to an era of “mass unemployment, mediocre wage growth and weak mobility.” This has been the outcome of inept macroeconomic policy and trade and regulatory policies that were designed to redistribute income from those at the middle and bottom to the top. Most people would look to reverse these policies rather than eliminate social insurance.

The implication of this comment, that we would somehow be able to make up substantial funding shortfalls from cutting taxes on low and middle income people by taxing the wealthy more also is not very plausible. Given the enormous political power of the “job creators” (as demonstrated by the fact that people are not laughed out of town for using this term), it is unlikely that substantially more money will be raised from the wealthy to pay for Social Security. This means that in Douthat’s dream world we would be seeing large cuts in benefits.

He also is wrong with his arithmetic. The payroll tax certainly can cover the program’s expenses. In fact, had it not been for the upward redistribution of income over the last three decades, which nearly doubled the share of wage income going over the cap on taxable income, the projected 75-year shortfall would be about half of its current level.

Even with the current projected shortfall, if ordinary workers shared in projected productivity growth over the next three decades, a tax increase equal to 6 percent of their wage growth over this period would be sufficient to make the program fully solvent. The problem is clearly the policies that led to the upward redistribution of income (e.g. protectionist policies for higher paid professionals, stronger patent and copyright monopolies, subsidies for too big to fail banks etc.), not Social Security.

It is worth pointing out that when Douthat proposes “means-testing for wealthier beneficiaries,” his notion of wealthy means school teachers and firefighters, not Bill Gates and Mitt Romney. There are a small number of very rich people, cutting some or all of their benefits won’t make any difference to the program’s finances. In order to have any appreciable effect on Social Security’s finances it would be necessary to cut benefits for people who earned $40,000 a year or thereabout.

Finally, Douthat refers to “changing the way benefits adjust for inflation.” Douthat is not interested in “changing the way benefits adjust for inflation,” he is interested in reducing the way that benefits adjust for inflation. The most widely touted proposal would be equivalent to a 3.0 percent cut in lifetime benefits. This would have a larger impact of the income of most beneficiaries than the ending of the Bush tax cuts would on the after-tax income of most of those affected. For this reason, it is understandable that there would be resistance just as there is considerable resistance to “changing” the tax rate for high income taxpayers.

Ross Douthat argues convincingly that if we eliminated the link between contributions and benefits it would be much easier politically to cut Social Security. Of course he thinks ending the link would be a good idea for that reason, but his logic is certainly on the mark, people will more strongly protect benefits that they feel they have earned.

Douthat is off on a few other points. He tells readers:

“In an era of mass unemployment, mediocre wage growth and weak mobility from the bottom of the income ladder, it makes no sense to finance our retirement system with a tax that falls directly on wages and hiring and imposes particular burdens on small business and the working class.

“What’s more, the payroll tax as it exists today can’t cover the program’s projected liabilities anyway, and the pay-as-you-go myth stands in the way of the changes required to keep Social Security solvent.”

The problem here is that we are not condemned to an era of “mass unemployment, mediocre wage growth and weak mobility.” This has been the outcome of inept macroeconomic policy and trade and regulatory policies that were designed to redistribute income from those at the middle and bottom to the top. Most people would look to reverse these policies rather than eliminate social insurance.

The implication of this comment, that we would somehow be able to make up substantial funding shortfalls from cutting taxes on low and middle income people by taxing the wealthy more also is not very plausible. Given the enormous political power of the “job creators” (as demonstrated by the fact that people are not laughed out of town for using this term), it is unlikely that substantially more money will be raised from the wealthy to pay for Social Security. This means that in Douthat’s dream world we would be seeing large cuts in benefits.

He also is wrong with his arithmetic. The payroll tax certainly can cover the program’s expenses. In fact, had it not been for the upward redistribution of income over the last three decades, which nearly doubled the share of wage income going over the cap on taxable income, the projected 75-year shortfall would be about half of its current level.

Even with the current projected shortfall, if ordinary workers shared in projected productivity growth over the next three decades, a tax increase equal to 6 percent of their wage growth over this period would be sufficient to make the program fully solvent. The problem is clearly the policies that led to the upward redistribution of income (e.g. protectionist policies for higher paid professionals, stronger patent and copyright monopolies, subsidies for too big to fail banks etc.), not Social Security.

It is worth pointing out that when Douthat proposes “means-testing for wealthier beneficiaries,” his notion of wealthy means school teachers and firefighters, not Bill Gates and Mitt Romney. There are a small number of very rich people, cutting some or all of their benefits won’t make any difference to the program’s finances. In order to have any appreciable effect on Social Security’s finances it would be necessary to cut benefits for people who earned $40,000 a year or thereabout.

Finally, Douthat refers to “changing the way benefits adjust for inflation.” Douthat is not interested in “changing the way benefits adjust for inflation,” he is interested in reducing the way that benefits adjust for inflation. The most widely touted proposal would be equivalent to a 3.0 percent cut in lifetime benefits. This would have a larger impact of the income of most beneficiaries than the ending of the Bush tax cuts would on the after-tax income of most of those affected. For this reason, it is understandable that there would be resistance just as there is considerable resistance to “changing” the tax rate for high income taxpayers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There is a large economic literature that shows how trade protection, which might raise the price of products by 15-20 percent, leads to political corruption. The argument is that the beneficiaries of this protection will use their political power to try to maximize the rents they get from this protection.

For some reason economists have not shown the same concern over the granting of patent monopolies which can raises the price of the protected product many thousand percent above the free market price. This is especially an issue in the case of prescription drugs. Drugs that would sell for $5-$10 per prescription as generics in a chain drug store instead sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars per prescription because of the government granted patent monopoly. The matter is complicated further by the enormous asymmetry in knowledge: the drug company knows much more about their drugs than doctors or patients.

The Washington Post has an excellent front page story that documents how drug company abuses in the research process have been a growing problem over the years. Unfortunately when discussing solutions it does not consider the idea of just taking the financing of clinical trials out of the hands of the industry as proposed by Nobel Laureate Joe Stiglitz. This idea was introduced into legislation earlier this year by Senator Bernie Sanders.

There is a large economic literature that shows how trade protection, which might raise the price of products by 15-20 percent, leads to political corruption. The argument is that the beneficiaries of this protection will use their political power to try to maximize the rents they get from this protection.

For some reason economists have not shown the same concern over the granting of patent monopolies which can raises the price of the protected product many thousand percent above the free market price. This is especially an issue in the case of prescription drugs. Drugs that would sell for $5-$10 per prescription as generics in a chain drug store instead sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars per prescription because of the government granted patent monopoly. The matter is complicated further by the enormous asymmetry in knowledge: the drug company knows much more about their drugs than doctors or patients.

The Washington Post has an excellent front page story that documents how drug company abuses in the research process have been a growing problem over the years. Unfortunately when discussing solutions it does not consider the idea of just taking the financing of clinical trials out of the hands of the industry as proposed by Nobel Laureate Joe Stiglitz. This idea was introduced into legislation earlier this year by Senator Bernie Sanders.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

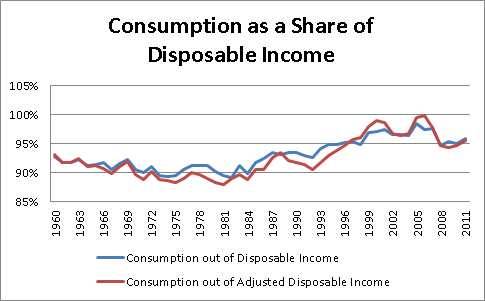

People who are familiar with the Commerce Department’s National Income and Product Accounts know that consumption as a share of disposable income is high by historic standards, not low, as shown in the beautiful graph below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, consumption as a share of disposable income is higher than at any point in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and even most of the 90s until the stock bubble generated a consumption boom. It is lower than at the peak of the housing bubble, but that’s what happens when you lose $8 trillion in housing wealth. (Adjusted disposable income has to do with the treatment of the statistical discrepancy in the national accounts.)

Given the actual path of consumption over the post-war years, readers of the Post editorial were undoubtedly shocked to see its conclusion:

“Housing is healing, albeit slowly, as are household balance sheets. Deutsche Bank economist Joseph LaVorgna estimates that households are on course to wipe out the excessive leverage of the bubble years within 15 months. This sets the stage for renewed consumer spending.”

The Post seems to be expecting bubble levels of consumption without bubble levels of wealth. That would truly be surprising, especially in a political environment in which all the serious people in Washington are openly plotting to cut Social Security and Medicare. What economic theory would tell us that we should see saving rates fall to levels that are far below normal in such an environment?

The other bizarre part of this story is that the Post seems to think that consumption is an on/off switch, telling us that households reaching some ill-described threshold of paying down of debt:

“sets the stage for renewed consumer spending.”

That makes no sense. The paying down of debt is a process in which tens of millions of households are paying down debt, while tens of millions are acquiring more. We reduce aggregate debt when the former exceeds the latter. We don’t hit some magic threshold and suddenly get a burst of consumption, rather we should be a seeing a continuing rise in the ratio of consumption to disposable income if the debt paydown is having the predicted effect (we haven’t).

Access to the Internet could help to address the Post’s misunderstanding about current consumption levels. I’m afraid that they will need some additional training in economics or logic to clear up the confusion about how debt could affect consumption.

People who are familiar with the Commerce Department’s National Income and Product Accounts know that consumption as a share of disposable income is high by historic standards, not low, as shown in the beautiful graph below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, consumption as a share of disposable income is higher than at any point in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and even most of the 90s until the stock bubble generated a consumption boom. It is lower than at the peak of the housing bubble, but that’s what happens when you lose $8 trillion in housing wealth. (Adjusted disposable income has to do with the treatment of the statistical discrepancy in the national accounts.)

Given the actual path of consumption over the post-war years, readers of the Post editorial were undoubtedly shocked to see its conclusion:

“Housing is healing, albeit slowly, as are household balance sheets. Deutsche Bank economist Joseph LaVorgna estimates that households are on course to wipe out the excessive leverage of the bubble years within 15 months. This sets the stage for renewed consumer spending.”

The Post seems to be expecting bubble levels of consumption without bubble levels of wealth. That would truly be surprising, especially in a political environment in which all the serious people in Washington are openly plotting to cut Social Security and Medicare. What economic theory would tell us that we should see saving rates fall to levels that are far below normal in such an environment?

The other bizarre part of this story is that the Post seems to think that consumption is an on/off switch, telling us that households reaching some ill-described threshold of paying down of debt:

“sets the stage for renewed consumer spending.”

That makes no sense. The paying down of debt is a process in which tens of millions of households are paying down debt, while tens of millions are acquiring more. We reduce aggregate debt when the former exceeds the latter. We don’t hit some magic threshold and suddenly get a burst of consumption, rather we should be a seeing a continuing rise in the ratio of consumption to disposable income if the debt paydown is having the predicted effect (we haven’t).

Access to the Internet could help to address the Post’s misunderstanding about current consumption levels. I’m afraid that they will need some additional training in economics or logic to clear up the confusion about how debt could affect consumption.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

News stories have been filled with reports of managers of manufacturing companies insisting that they have jobs open that they can’t fill because there are no qualified workers. Adam Davidson at the NYT looked at this more closely and found that the real problem is that the managers don’t seem to be interested in paying for the high level of skills that they claim they need.

Many of the positions that are going unfilled pay in the range of $15-$20 an hour. This is not a pay level that would be associated with a job that requires a high degree of skill. As Davidson points out, low level managers at a fast-food restaurant can make comparable pay.

It should not be surprising that the workers who have these skills expect higher pay and workers without the skills will not invest the time and money to acquire them for such a small reward. If these factories want to get highly skilled workers, they will have to offer a wage that is in line with the skill level that they expect.

News stories have been filled with reports of managers of manufacturing companies insisting that they have jobs open that they can’t fill because there are no qualified workers. Adam Davidson at the NYT looked at this more closely and found that the real problem is that the managers don’t seem to be interested in paying for the high level of skills that they claim they need.

Many of the positions that are going unfilled pay in the range of $15-$20 an hour. This is not a pay level that would be associated with a job that requires a high degree of skill. As Davidson points out, low level managers at a fast-food restaurant can make comparable pay.

It should not be surprising that the workers who have these skills expect higher pay and workers without the skills will not invest the time and money to acquire them for such a small reward. If these factories want to get highly skilled workers, they will have to offer a wage that is in line with the skill level that they expect.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión