Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The paper has a huge front page story showing the hit to the economy from each of the components of the showdown (e.g. the specific tax cuts that are ending and the various spending cuts). The problem is that what the article shows as the hit to the economy is the hit if nothing is done all year, it has zero, nothing, nada, to do with the impact of letting the December 31st deadline pass, with the tax increases and spending cuts reversed early in 2013. It is unlikely that many USA Today readers will recognize this fact and therefore will be badly misled by this front page article. (Given this fact, it is difficult to see why USA Today would devote so much space to this graph.)

The Republicans are working hard to try to build up fears around this deadline because they know that President Obama will be in a much better negotiating position after the end of the year. The USA Today piece fits with this agenda.

The paper has a huge front page story showing the hit to the economy from each of the components of the showdown (e.g. the specific tax cuts that are ending and the various spending cuts). The problem is that what the article shows as the hit to the economy is the hit if nothing is done all year, it has zero, nothing, nada, to do with the impact of letting the December 31st deadline pass, with the tax increases and spending cuts reversed early in 2013. It is unlikely that many USA Today readers will recognize this fact and therefore will be badly misled by this front page article. (Given this fact, it is difficult to see why USA Today would devote so much space to this graph.)

The Republicans are working hard to try to build up fears around this deadline because they know that President Obama will be in a much better negotiating position after the end of the year. The USA Today piece fits with this agenda.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It seems that WonkBlog is picking up some of the Washington Post’s bad habits. The Post was a strong supporter of NAFTA when the trade agreement was being debated, virtually closing its news and opinion pages to critics of the deal. In the almost two decades since NAFTA passed the Post has run numerous pieces touting the benefits of the agreement for both Mexico and the United States.

The praise has been especially off the mark in the case of Mexico. In spite of having the lowest per capita growth of any country in Latin America over the last decade, the Post has routinely run pieces highlighting the boom in Mexico and the country’s growing middle class (e.g. see here and here). The Post even claimed in a 2007 editorial that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1988. (The actual growth number was 83 percent.)

WonkBlog has a piece that cites a new paper and claims that NAFTA has been good for all involved, showing GDP and wage gains for Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. While this is in fact the conclusion of the study, it would have been worth including some qualifying remarks.

For example, the study explicitly assumes that there is only one type of labor. (The bottom of page 26 explains that in the modeling exercise there is “one wage per

country.”) This simplifying assumption can be useful for some purposes, but if the question is whether NAFTA might have hurt less-educated workers (e.g. autoworkers and steelworkers) to the benefit of more highly educated workers (e.g. doctors and lawyers), it cannot be answered with a model where there is one type of labor.

This upward redistribution is exactly what fans of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem would expect from a trade agreement like NAFTA. Therefore this model can not be used to tell us whether NAFTA would have had one of the negative effects predicted by economic theory.

The other big item missing from this model is the impact of stronger patent and copyright protections. NAFTA required Mexico to develop a U.S. style patent system which substantially raised the cost of prescription drugs and other products in Mexico. This model makes no effort to measure the impact of this increased protectionism on the Mexican economy directly, or indirectly on the other two economies. Insofar as this interference with the free market led to higher prices and increased distortions, it would be expected to slow growth, but obviously that effect cannot be picked up in this model.

In short, the model highlighted in this post can be useful for some purposes but it cannot possibly provide a basis for telling us whether NAFTA was on net good or bad for the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

Correction:

An earlier verison referred to “Wongblog.”

It seems that WonkBlog is picking up some of the Washington Post’s bad habits. The Post was a strong supporter of NAFTA when the trade agreement was being debated, virtually closing its news and opinion pages to critics of the deal. In the almost two decades since NAFTA passed the Post has run numerous pieces touting the benefits of the agreement for both Mexico and the United States.

The praise has been especially off the mark in the case of Mexico. In spite of having the lowest per capita growth of any country in Latin America over the last decade, the Post has routinely run pieces highlighting the boom in Mexico and the country’s growing middle class (e.g. see here and here). The Post even claimed in a 2007 editorial that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1988. (The actual growth number was 83 percent.)

WonkBlog has a piece that cites a new paper and claims that NAFTA has been good for all involved, showing GDP and wage gains for Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. While this is in fact the conclusion of the study, it would have been worth including some qualifying remarks.

For example, the study explicitly assumes that there is only one type of labor. (The bottom of page 26 explains that in the modeling exercise there is “one wage per

country.”) This simplifying assumption can be useful for some purposes, but if the question is whether NAFTA might have hurt less-educated workers (e.g. autoworkers and steelworkers) to the benefit of more highly educated workers (e.g. doctors and lawyers), it cannot be answered with a model where there is one type of labor.

This upward redistribution is exactly what fans of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem would expect from a trade agreement like NAFTA. Therefore this model can not be used to tell us whether NAFTA would have had one of the negative effects predicted by economic theory.

The other big item missing from this model is the impact of stronger patent and copyright protections. NAFTA required Mexico to develop a U.S. style patent system which substantially raised the cost of prescription drugs and other products in Mexico. This model makes no effort to measure the impact of this increased protectionism on the Mexican economy directly, or indirectly on the other two economies. Insofar as this interference with the free market led to higher prices and increased distortions, it would be expected to slow growth, but obviously that effect cannot be picked up in this model.

In short, the model highlighted in this post can be useful for some purposes but it cannot possibly provide a basis for telling us whether NAFTA was on net good or bad for the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

Correction:

An earlier verison referred to “Wongblog.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

What is wrong with these people who keep talking about a Bowles-Simpson Commission report? This one is not a debatable point. There was no Bowles-Simpson Commission report. That’s a fact, just like the fact that Governor Romney lost the election.

Look it up. The by-laws of the commission say:

“The Commission shall vote on the approval of a final report containing a set of recommendations to achieve the objectives set forth in the Charter no later than December 1, 2010. The issuance of a final report of the Commission shall require the approval of not less than 14 of the 18 members of the Commission.”

There was no vote on anything by December 1, 2010 and there was no report that had the approval of 14 of the 18 members of the commission. Therefore there was no commission report. The correct way to refer to the document in question is the report of the co-chairs.

Today’s guilty parties are David Leonhardt at the NYT and Steve Pearlstein at the Post. Come on folks, a lot of Republicans really wanted Romney to get elected, but that doesn’t make him president. And, no matter how much you guys like the Bowles-Simpson report, there was no report from the commission. Let’s get back to reality.

What is wrong with these people who keep talking about a Bowles-Simpson Commission report? This one is not a debatable point. There was no Bowles-Simpson Commission report. That’s a fact, just like the fact that Governor Romney lost the election.

Look it up. The by-laws of the commission say:

“The Commission shall vote on the approval of a final report containing a set of recommendations to achieve the objectives set forth in the Charter no later than December 1, 2010. The issuance of a final report of the Commission shall require the approval of not less than 14 of the 18 members of the Commission.”

There was no vote on anything by December 1, 2010 and there was no report that had the approval of 14 of the 18 members of the commission. Therefore there was no commission report. The correct way to refer to the document in question is the report of the co-chairs.

Today’s guilty parties are David Leonhardt at the NYT and Steve Pearlstein at the Post. Come on folks, a lot of Republicans really wanted Romney to get elected, but that doesn’t make him president. And, no matter how much you guys like the Bowles-Simpson report, there was no report from the commission. Let’s get back to reality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker is a hero to the inside Washington crowd for having brought down inflation from its double-digit levels of the late 1970s. Never mind that this drop in the inflation rate occurred in every other country in the world also. We still must praise Volcker.

We also should not be bothered by the fact that his policy pushed the unemployment rate to almost 11 percent. This was necessary pain that those outside the elite just had to endure for the good of the country as a whole. We also are not supposed to be bothered by what his high interest policies did to heavily indebted developing countries.

But putting all this aside, the Volcker worshippers should at least be able to get the basic facts right. Steven Pearlstein flunks the test in a WAPO book review when he tells readers:

“By the time he stepped down as Fed chairman in 1987, Volcker had managed to wring inflation out of the American psyche and bring the country’s trade account and the government’s budget much closer toward balance.”

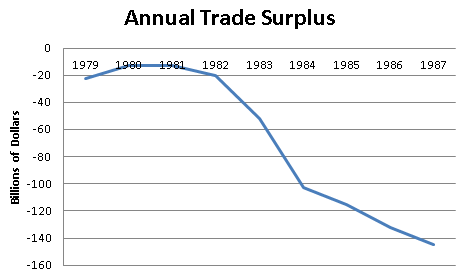

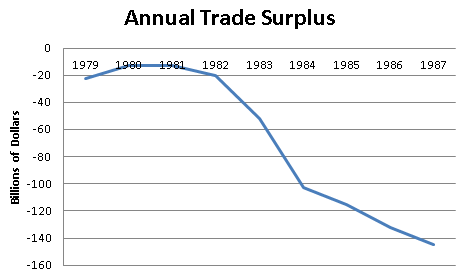

This is not true, the trade deficit in fact soared during the Volcker years as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Expressed as a share of GDP, the trade deficit went from 0.8 percent in 1979 to 3.0 percent in 1987. It really shouldn’t be hard to get this one right.

Addendum:

In response to several comments below I have corrected the graph to show the “surplus” not deficit becoming more negative under Volcker. This was arguably the direct result of his Fed policy, since a predicted result of higher interest rates is a rise in the value of the dollar which makes U.S. goods less competitive internationally.

Former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker is a hero to the inside Washington crowd for having brought down inflation from its double-digit levels of the late 1970s. Never mind that this drop in the inflation rate occurred in every other country in the world also. We still must praise Volcker.

We also should not be bothered by the fact that his policy pushed the unemployment rate to almost 11 percent. This was necessary pain that those outside the elite just had to endure for the good of the country as a whole. We also are not supposed to be bothered by what his high interest policies did to heavily indebted developing countries.

But putting all this aside, the Volcker worshippers should at least be able to get the basic facts right. Steven Pearlstein flunks the test in a WAPO book review when he tells readers:

“By the time he stepped down as Fed chairman in 1987, Volcker had managed to wring inflation out of the American psyche and bring the country’s trade account and the government’s budget much closer toward balance.”

This is not true, the trade deficit in fact soared during the Volcker years as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Expressed as a share of GDP, the trade deficit went from 0.8 percent in 1979 to 3.0 percent in 1987. It really shouldn’t be hard to get this one right.

Addendum:

In response to several comments below I have corrected the graph to show the “surplus” not deficit becoming more negative under Volcker. This was arguably the direct result of his Fed policy, since a predicted result of higher interest rates is a rise in the value of the dollar which makes U.S. goods less competitive internationally.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post is intensifying its push for cuts to Social Security and Medicare apparently hoping for action in the lame duck Congressional session. Today a story in the news section told readers:

“On entitlements, Obama has offered significant changes to Medicare, including letting the eligibility age to rise from 65 to 67.”

The passive tense in this sentence might confuse readers. President Obama proposed raising the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 67. This is not something that happens absent his effort to stop it, like the rise of the oceans due to global warming. Obama would be the agent of this increase in the age of eligibility. Experienced reporters and editors usually would not make this sort of mistake.

The next sentence tells readers:

“He has also supported applying a less generous measure of inflation to Social Security benefits.”

Okay, does everyone know what this means? I suspect that only a small minority of Post readers understands that “applying a less generous measure of inflation” implies a cut in the annual cost of living adjustment of 0.3 percentage points. This cut would be cumulative so that after being retired 10 years a beneficiary would see a cut of approximately 3 percent, after 20 years the cut would 6 percent and after 30 years it would be 9 percent.

Newspapers are supposed to be trying to inform their readers. It is difficult to believe that the Post’s terminology in this sentence was its best effort at informing readers of the meaning of this proposal. It is perhaps worth noting that this proposed cut in benefits is hugely unpopular.

At another point the Post discussed the contours of the budget dispute and told readers:

“one of the sticking points remains relevant: Although Democrats wanted to increase the tab [revenue increases] for taxpayers by $800 billion, Republicans wanted at least some of the money to come from economic growth, ….”

A real newspaper would write the second part of this sentence:

“Republicans wanted to claim at least some of the money would come from economic growth”

Undoubtedly both Republicans and Democrats would be happy if the government got additional revenue as a result of more rapid economic growth. The difference is that the Republicans want to score the additional revenue as part of the budget agreement, making assumptions about the impact of lower tax rates on growth that may not be warranted by the evidence. Most Post readers probably would not understand this fact.

The Washington Post is intensifying its push for cuts to Social Security and Medicare apparently hoping for action in the lame duck Congressional session. Today a story in the news section told readers:

“On entitlements, Obama has offered significant changes to Medicare, including letting the eligibility age to rise from 65 to 67.”

The passive tense in this sentence might confuse readers. President Obama proposed raising the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 67. This is not something that happens absent his effort to stop it, like the rise of the oceans due to global warming. Obama would be the agent of this increase in the age of eligibility. Experienced reporters and editors usually would not make this sort of mistake.

The next sentence tells readers:

“He has also supported applying a less generous measure of inflation to Social Security benefits.”

Okay, does everyone know what this means? I suspect that only a small minority of Post readers understands that “applying a less generous measure of inflation” implies a cut in the annual cost of living adjustment of 0.3 percentage points. This cut would be cumulative so that after being retired 10 years a beneficiary would see a cut of approximately 3 percent, after 20 years the cut would 6 percent and after 30 years it would be 9 percent.

Newspapers are supposed to be trying to inform their readers. It is difficult to believe that the Post’s terminology in this sentence was its best effort at informing readers of the meaning of this proposal. It is perhaps worth noting that this proposed cut in benefits is hugely unpopular.

At another point the Post discussed the contours of the budget dispute and told readers:

“one of the sticking points remains relevant: Although Democrats wanted to increase the tab [revenue increases] for taxpayers by $800 billion, Republicans wanted at least some of the money to come from economic growth, ….”

A real newspaper would write the second part of this sentence:

“Republicans wanted to claim at least some of the money would come from economic growth”

Undoubtedly both Republicans and Democrats would be happy if the government got additional revenue as a result of more rapid economic growth. The difference is that the Republicans want to score the additional revenue as part of the budget agreement, making assumptions about the impact of lower tax rates on growth that may not be warranted by the evidence. Most Post readers probably would not understand this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión