Steven Davidoff used a Dealbook column to defend the investment banks behavior in selling collaterized debt obligations (CDOs) filled with bad mortgages. While he does make an important point, he glides over some clearly improper and possibly illegal behavior on the part of the banks.

Davidoff notes that the CDOs in question were sold to people who certainly should have been sophisticated investors and who were clearly warned that Goldman Sachs and other banks were not acting as investment advisers in the deal. In other words, the buyers were people managing hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in assets, who were given explicit warnings that the sellers were not recommending the assets as a good investment.

Given that these people were paid six or even seven figure salaries, it was reasonable to expect that they would do their homework and independently seek to evaluate the quality of the assets they were buying. If they did not independently assess the quality of the assets then they are the ones most immediately to blame, not the sellers.

However, Davidoff does glide over a key misrepresentation in at least one case. The synthetic CDO Abacus, that Goldman Sachs sold to its clients, was put together by John Paulson who was shorting the CDO. In this case, Goldman presented itself to its clients as a neutral party not, as was actually the case, an agent for the person shorting the CDO. This was a fundamental misrepresentation.

If there were similar misrepresentations in the other cases Davidoff notes, then the banks deserve to be held at least partially responsible for the losses incurred. Sophisticated buyers should do the homework for which they are being paid very generous salaries. However this failure does not excuse misrepresentations that border on fraud by the sellers.

There is one other important point in this story worth noting. All the bad news from the housing bubble was already baked in at the point where these deals were made. The bubble peaked in the summer of 2006 and was headed down by the start of 2007. The economic collapse would have occurred regardless of whether or not these CDO deals took place. These deals simply affected the distribution of the losses among the big players. They did not cause the losses to occur.

Steven Davidoff used a Dealbook column to defend the investment banks behavior in selling collaterized debt obligations (CDOs) filled with bad mortgages. While he does make an important point, he glides over some clearly improper and possibly illegal behavior on the part of the banks.

Davidoff notes that the CDOs in question were sold to people who certainly should have been sophisticated investors and who were clearly warned that Goldman Sachs and other banks were not acting as investment advisers in the deal. In other words, the buyers were people managing hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in assets, who were given explicit warnings that the sellers were not recommending the assets as a good investment.

Given that these people were paid six or even seven figure salaries, it was reasonable to expect that they would do their homework and independently seek to evaluate the quality of the assets they were buying. If they did not independently assess the quality of the assets then they are the ones most immediately to blame, not the sellers.

However, Davidoff does glide over a key misrepresentation in at least one case. The synthetic CDO Abacus, that Goldman Sachs sold to its clients, was put together by John Paulson who was shorting the CDO. In this case, Goldman presented itself to its clients as a neutral party not, as was actually the case, an agent for the person shorting the CDO. This was a fundamental misrepresentation.

If there were similar misrepresentations in the other cases Davidoff notes, then the banks deserve to be held at least partially responsible for the losses incurred. Sophisticated buyers should do the homework for which they are being paid very generous salaries. However this failure does not excuse misrepresentations that border on fraud by the sellers.

There is one other important point in this story worth noting. All the bad news from the housing bubble was already baked in at the point where these deals were made. The bubble peaked in the summer of 2006 and was headed down by the start of 2007. The economic collapse would have occurred regardless of whether or not these CDO deals took place. These deals simply affected the distribution of the losses among the big players. They did not cause the losses to occur.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m not kidding. If you get through the excess verbiage in his column, the main point is that President Obama hasn’t moved to cut Social Security and Medicare in his first term. This is what Brooks means when he says:

“get our long-term entitlement burdens under control, get our political system working, shift government resources from the affluent elderly to struggling young families and future growth,”

and by his later call for “sacrifice.” Of course Brooks doesn’t really mean “affluent” elderly. We know that Brooks and his political allies question whether even people earning above $250,000 a year are affluent when it comes to tax cuts. If the cuts in Social Security and Medicare were restricted to this group then we would barely need to change the projections for these programs. There are so few seniors with incomes above this cutoff that whether or not they get Medicare and Social Security makes almost no difference to the financial health of these programs.

Brooks wants to see Obama cut benefits for retired nurses, school teachers, truck drivers and other middle class workers. That is the only way to produce real savings in these programs. And, in spite of indicating a willingness to make cuts in these programs, Obama has not delivered in his first term. So just as many Democrats were disappointed that President Bush hadn’t provided universal health care or taken steps to curb global warming in his first term, David Brooks is upset that President Obama has not cut Social Security and Medicare.

(Btw, just in case anyone was wondering, more pain for the middle class is not necessary as Brooks asserts. As every budget wonk knows, the problem is simply fixing our broken health care system. If our per person health care costs were anywhere close to costs in other wealthy countries, we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficits.)

I’m not kidding. If you get through the excess verbiage in his column, the main point is that President Obama hasn’t moved to cut Social Security and Medicare in his first term. This is what Brooks means when he says:

“get our long-term entitlement burdens under control, get our political system working, shift government resources from the affluent elderly to struggling young families and future growth,”

and by his later call for “sacrifice.” Of course Brooks doesn’t really mean “affluent” elderly. We know that Brooks and his political allies question whether even people earning above $250,000 a year are affluent when it comes to tax cuts. If the cuts in Social Security and Medicare were restricted to this group then we would barely need to change the projections for these programs. There are so few seniors with incomes above this cutoff that whether or not they get Medicare and Social Security makes almost no difference to the financial health of these programs.

Brooks wants to see Obama cut benefits for retired nurses, school teachers, truck drivers and other middle class workers. That is the only way to produce real savings in these programs. And, in spite of indicating a willingness to make cuts in these programs, Obama has not delivered in his first term. So just as many Democrats were disappointed that President Bush hadn’t provided universal health care or taken steps to curb global warming in his first term, David Brooks is upset that President Obama has not cut Social Security and Medicare.

(Btw, just in case anyone was wondering, more pain for the middle class is not necessary as Brooks asserts. As every budget wonk knows, the problem is simply fixing our broken health care system. If our per person health care costs were anywhere close to costs in other wealthy countries, we would be looking at long-term budget surpluses, not deficits.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post told readers that:

“the sharp improvement visible in the survey of households in the September jobs numbers may turn out to be a overly positive statistical aberration. An additional 872,000 people reported having a job in September’s household survey, which does not square with the amount of hiring that employers reported.”

While this is true for the September numbers, the data look less anomalous if we take into account that the household survey reported a fall in employment of 314,000 jobs in the prior two months. The total employment growth of 559,000 reported over the last three months is not very different from the 437,000 job growth reported over this period in the establishment survey. (It is still likely the unemployment rate will rise this month — this rate of job growth is not consistent with a sharp drop in the unemployment rate.)

The Washington Post told readers that:

“the sharp improvement visible in the survey of households in the September jobs numbers may turn out to be a overly positive statistical aberration. An additional 872,000 people reported having a job in September’s household survey, which does not square with the amount of hiring that employers reported.”

While this is true for the September numbers, the data look less anomalous if we take into account that the household survey reported a fall in employment of 314,000 jobs in the prior two months. The total employment growth of 559,000 reported over the last three months is not very different from the 437,000 job growth reported over this period in the establishment survey. (It is still likely the unemployment rate will rise this month — this rate of job growth is not consistent with a sharp drop in the unemployment rate.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Census Bureau reported this week that housing vacancy rates in the third quarter were substantially lower than their year ago level. The vacancy rates for rental units fell from 9.8 percent in the third quarter of 2011 to 8.6 percent this year. The vacancy rate for ownership units from 2.4 percent to 1.9 percent. (There are roughly twice as many ownership units as rental units.) The third data quarter data indicates that the housing market is substantially tighter than it was 2-3 years ago, even though vacancy rates are still well above pre-bubble levels.

It is remarkable that the vacancy data receive so little attention. These data were one of the ways that economists could have recognized the housing bubble. While house prices were going through the roof in the years 2002-2006, the vacancy rate was continually hitting new records. Concepts taught in advanced economics classes indicate that the price of items in excess supply are not supposed to be rising. It was therefore not reasonable to expect the run-up in house prices to be sustained given the large amounts of vacant housing available. The reduction in the excess supply is consistent with other data showing a recovering housing market.

The Census Bureau reported this week that housing vacancy rates in the third quarter were substantially lower than their year ago level. The vacancy rates for rental units fell from 9.8 percent in the third quarter of 2011 to 8.6 percent this year. The vacancy rate for ownership units from 2.4 percent to 1.9 percent. (There are roughly twice as many ownership units as rental units.) The third data quarter data indicates that the housing market is substantially tighter than it was 2-3 years ago, even though vacancy rates are still well above pre-bubble levels.

It is remarkable that the vacancy data receive so little attention. These data were one of the ways that economists could have recognized the housing bubble. While house prices were going through the roof in the years 2002-2006, the vacancy rate was continually hitting new records. Concepts taught in advanced economics classes indicate that the price of items in excess supply are not supposed to be rising. It was therefore not reasonable to expect the run-up in house prices to be sustained given the large amounts of vacant housing available. The reduction in the excess supply is consistent with other data showing a recovering housing market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would be the conclusion of folks who played with its interactive calculator on ways to have President Obama reach his deficit reduction target. The calculator includes several possible taxes which it identifies as “the most popular proposals for wholly new sources of revenue.” A financial speculation tax is not included on the list. It does include a value-added tax (VAT), which would effectively be a national sales tax.

A bill calling for a financial speculation tax was sponsored last year by Tom Harkin in the Senate and Peter DeFazio in the House. According to the Joint Tax Committee, the tax would raise almost $40 billion a year in revenue. It has a number of co-sponsors in both chambers. By contrast, there is no current bill calling for a VAT and if any members of Congress support one, they are keeping pretty quiet.

Perhaps there are some poll results showing a great desire for a VAT. Otherwise, we can assume that the decision to include a VAT on the calculator and to exclude a financial speculation tax reflects the relative popularity of the two taxes at the Washington Post.

That would be the conclusion of folks who played with its interactive calculator on ways to have President Obama reach his deficit reduction target. The calculator includes several possible taxes which it identifies as “the most popular proposals for wholly new sources of revenue.” A financial speculation tax is not included on the list. It does include a value-added tax (VAT), which would effectively be a national sales tax.

A bill calling for a financial speculation tax was sponsored last year by Tom Harkin in the Senate and Peter DeFazio in the House. According to the Joint Tax Committee, the tax would raise almost $40 billion a year in revenue. It has a number of co-sponsors in both chambers. By contrast, there is no current bill calling for a VAT and if any members of Congress support one, they are keeping pretty quiet.

Perhaps there are some poll results showing a great desire for a VAT. Otherwise, we can assume that the decision to include a VAT on the calculator and to exclude a financial speculation tax reflects the relative popularity of the two taxes at the Washington Post.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article on the problems facing France’s president Francoise Hollande included several peculiar assertions. At one point it noted Hollande’s efforts to meet a deficit target of 3 percent of GDP (strangely labeled as “economic rigor”) and then tells readers:

“Others complained that Mr. Hollande’s decision to meet the target by raising taxes and freezing spending, rather than cutting it, would throw France into recession, even as growth, so far elusive, would by itself provide more tax receipts and jobs.”

There is no obvious economic theory whereby spending cuts would be less contractionary in the short term than tax increases on the wealthy. If Hollande cut spending by 30 billion euros rather than raising taxes by the same amount, the spending cuts would almost certainly do more to cut jobs and reduce growth. (It might have been useful to disclose the identity of the “others.”)

The piece later tells readers:

“He [Hollande] has also sent mixed messages — vowing that France will not undergo austerity while raising taxes on companies and the rich, and at the same time trying to show that he is fiscally responsible to the markets and his euro zone allies.”

It’s not clear what the mixed message is here. It seems that Hollande is trying to reduce France’s budget deficit by imposing taxes on people who have money rather than hitting ordinary workers and retirees. There is nothing obviously contradictory in this picture.

A NYT article on the problems facing France’s president Francoise Hollande included several peculiar assertions. At one point it noted Hollande’s efforts to meet a deficit target of 3 percent of GDP (strangely labeled as “economic rigor”) and then tells readers:

“Others complained that Mr. Hollande’s decision to meet the target by raising taxes and freezing spending, rather than cutting it, would throw France into recession, even as growth, so far elusive, would by itself provide more tax receipts and jobs.”

There is no obvious economic theory whereby spending cuts would be less contractionary in the short term than tax increases on the wealthy. If Hollande cut spending by 30 billion euros rather than raising taxes by the same amount, the spending cuts would almost certainly do more to cut jobs and reduce growth. (It might have been useful to disclose the identity of the “others.”)

The piece later tells readers:

“He [Hollande] has also sent mixed messages — vowing that France will not undergo austerity while raising taxes on companies and the rich, and at the same time trying to show that he is fiscally responsible to the markets and his euro zone allies.”

It’s not clear what the mixed message is here. It seems that Hollande is trying to reduce France’s budget deficit by imposing taxes on people who have money rather than hitting ordinary workers and retirees. There is nothing obviously contradictory in this picture.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is common for news reports on efforts to limit global warming with carbon taxes to mention the negative impact that such taxes can have on growth and jobs. In the same vein it is worth pointing out that the costs associated with damage caused by global warming related storms, like Sandy, also will in the long-run slow growth and reduce the number of jobs.

For example, this Washington Post article that noted estimates of the damage from Sandy are in the range of $30-$50 billion could have pointed out to readers that this will have an economic impact similar to a gas tax in the range of 25-40 cents a gallon. This tax will mostly be paid in the form of higher insurance premiums in future years.

It is important to point out the economic costs of failing to control global warming since many politicians are trying to deceive the public into believing that global warming has no costs.

It is common for news reports on efforts to limit global warming with carbon taxes to mention the negative impact that such taxes can have on growth and jobs. In the same vein it is worth pointing out that the costs associated with damage caused by global warming related storms, like Sandy, also will in the long-run slow growth and reduce the number of jobs.

For example, this Washington Post article that noted estimates of the damage from Sandy are in the range of $30-$50 billion could have pointed out to readers that this will have an economic impact similar to a gas tax in the range of 25-40 cents a gallon. This tax will mostly be paid in the form of higher insurance premiums in future years.

It is important to point out the economic costs of failing to control global warming since many politicians are trying to deceive the public into believing that global warming has no costs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

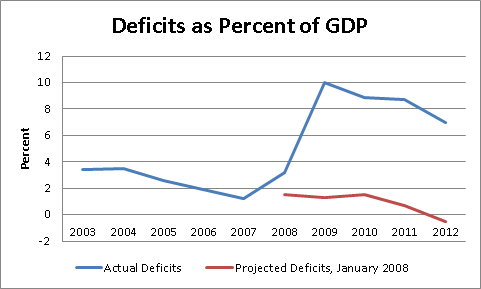

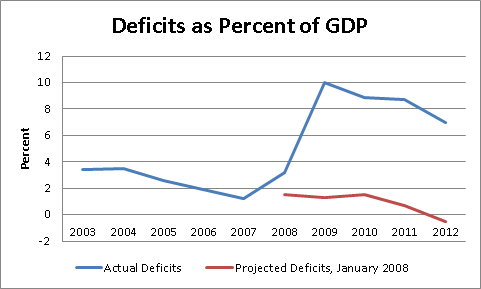

When NYT columnists make absurd assertions they deserve ridicule. In his NYT column today, David Brooks make the absurd assertion that, “the mounting debt is ruinous.” Right, and we know this because the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is less than 1.8 percent? (That compares to rates of more than 5.0 percent when we had budget surpluses in the late 1990s.) Do we know that the mounting debt is “ruinous” because the ratio of interest on the debt to GDP is near a post-war low?

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

The real story is that the debt is not ruinous except in David Brooks’ head. He has no basis for this whatsoever. He is using fears of the debt to try to scare people to support his agenda in the way that others have appealed to racial or ethnic fears.

We have a large deficit because the economy plunged when the housing bubble collapsed. That is the story. The deficits are supporting the economy because the this collapse led to a massive loss of private sector demand. Without the deficit we would simply have lower GDP and higher unemployment, as all the “fiscal cliff” whiners are implicitly acknowledging. This fact is easily demonstrated by looking at the Congressional Budget Office projections from January of 2008 before it recognized the impact of the bubble’s collapse.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

There were no big new permanent government spending programs or tax cuts put in place in 2008 or 2009, the deficit exploded because of the economic collapse, end of story. Anyone who says otherwise is trying to mislead people deserves nothing but ridicule and derision.

When NYT columnists make absurd assertions they deserve ridicule. In his NYT column today, David Brooks make the absurd assertion that, “the mounting debt is ruinous.” Right, and we know this because the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is less than 1.8 percent? (That compares to rates of more than 5.0 percent when we had budget surpluses in the late 1990s.) Do we know that the mounting debt is “ruinous” because the ratio of interest on the debt to GDP is near a post-war low?

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

The real story is that the debt is not ruinous except in David Brooks’ head. He has no basis for this whatsoever. He is using fears of the debt to try to scare people to support his agenda in the way that others have appealed to racial or ethnic fears.

We have a large deficit because the economy plunged when the housing bubble collapsed. That is the story. The deficits are supporting the economy because the this collapse led to a massive loss of private sector demand. Without the deficit we would simply have lower GDP and higher unemployment, as all the “fiscal cliff” whiners are implicitly acknowledging. This fact is easily demonstrated by looking at the Congressional Budget Office projections from January of 2008 before it recognized the impact of the bubble’s collapse.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

There were no big new permanent government spending programs or tax cuts put in place in 2008 or 2009, the deficit exploded because of the economic collapse, end of story. Anyone who says otherwise is trying to mislead people deserves nothing but ridicule and derision.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT has apparently designed to join the crusade against the European welfare state. A profile of German Chancellor Angela Merkel noted that Europe accounts for 25 percent of world GDP, but a “staggering” 50 percent of social spending.

There is nothing obviously out of line in this story. Poor countries don’t have much by way of social spending. In the United States, benefits like health care and pension coverage are largely provided through employers. Europe has adopted a much more efficient route of providing these benefits through the government. There is no obvious problem with going this route from an economic standpoint.

The NYT should have found a reporter who could discuss such issues without being staggered by them.

The NYT has apparently designed to join the crusade against the European welfare state. A profile of German Chancellor Angela Merkel noted that Europe accounts for 25 percent of world GDP, but a “staggering” 50 percent of social spending.

There is nothing obviously out of line in this story. Poor countries don’t have much by way of social spending. In the United States, benefits like health care and pension coverage are largely provided through employers. Europe has adopted a much more efficient route of providing these benefits through the government. There is no obvious problem with going this route from an economic standpoint.

The NYT should have found a reporter who could discuss such issues without being staggered by them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión