Casey Mulligan misrepresented President Obama’s claims on unemployment insurance, making his plans to have deficit spending analogous to Governor Romney’s trickle down economics. Mulligan claims the two plans are analogous in the sense that Romney argues that ordinary workers can be made better off by redistributing income upwards, while Obama argues that business owners can be made better off by giving unemployed workers more generous unemployment benefits.

There is a fundamental difference in these arguments that Mulligan’s discussion conceals. Romney is claiming that he does not want to increase the deficit. His tax cuts for the wealthy would come at the expense of higher taxes on middle income workers.

By contrast, President Obama is proposing to keep higher levels of unemployment benefits that will be financed by larger budget deficits. This does not amount to a claim that a redistribution from one group to another will make the loser in this story better off, it depends on the idea that deficits in a downturn can boost economic growth.

It is possible to make an argument that deficits imply higher future tax burdens and that people will recognize this fact and reduce their spending accordingly, but that is a very strong assumption that seems to be implicit in Mulligan’s argument. For people who do not believe that most households factor the government’s debt into their spending and saving decisions, Obama’s argument is simply that putting more money into the hands of unemployed workers will lead to more spending and therefore more growth.

Casey Mulligan misrepresented President Obama’s claims on unemployment insurance, making his plans to have deficit spending analogous to Governor Romney’s trickle down economics. Mulligan claims the two plans are analogous in the sense that Romney argues that ordinary workers can be made better off by redistributing income upwards, while Obama argues that business owners can be made better off by giving unemployed workers more generous unemployment benefits.

There is a fundamental difference in these arguments that Mulligan’s discussion conceals. Romney is claiming that he does not want to increase the deficit. His tax cuts for the wealthy would come at the expense of higher taxes on middle income workers.

By contrast, President Obama is proposing to keep higher levels of unemployment benefits that will be financed by larger budget deficits. This does not amount to a claim that a redistribution from one group to another will make the loser in this story better off, it depends on the idea that deficits in a downturn can boost economic growth.

It is possible to make an argument that deficits imply higher future tax burdens and that people will recognize this fact and reduce their spending accordingly, but that is a very strong assumption that seems to be implicit in Mulligan’s argument. For people who do not believe that most households factor the government’s debt into their spending and saving decisions, Obama’s argument is simply that putting more money into the hands of unemployed workers will lead to more spending and therefore more growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post long ago ended the separation of its news and editorial departments, therefore it was not surprising to see the page three article complaining that “experts” are worried that the rhetoric of the presidential campaign will make it harder to find a “solution” for Medicare. As is standard practice, the Post’s corral of experts were exclusively people who largely agree with its editorial position on Medicare: that there have to be large cuts to the program.

The three people presented as experts in the piece are Robert Bixby, the executive director of the Peter Peterson funded Concord Coalition, Steve Bell, economic policy director at the Peter Peterson funded Bipartisan Policy Center and a former Republican congressional staffer, Dougas Holtz-Eakin, a former director of the Congressional Budget Office and the top economic advisor to John McCain in his 2008 campaign. All three present views of Medicare and budget deficits that are very similar to the views expressed in the Post editorials.

It would have been easy to find experts presenting a broader range of views if the Post had wanted to write this piece as a real news story. For example, they could have spoken to Henry Aaron at the Brookings Institution who has written extensively on health care policy for decades. Or, they could have talked to M.I.T. economist Jon Gruber who played a central role in designing both Governor Romney’s health care plan for Massachusetts and President Obama’s health care plan.

A broader group of experts could have explained to readers that most of Medicare’s projected shortfall has already been eliminated by the cost control measures that President Obama put in place in the Affordable Care Act. The projected shortfall over 75 years fell from 3.88 percent of taxable payroll in the 2009 Medicare Trustees Report to 1.35 percent of taxable payroll in the 2012 Medicare Trustees Report. The experts the Post relied upon apparently neglected to mention the sharp reduction in the projected deficit as a result of President Obama’s policies.

A broader group of experts might also have reminded Post readers that the underlying problem is not the cost of Medicare but rather the cost of health care more generally in the United States. If we paid the same amount per person as people in any other wealthy country, there would be no Medicare problem whatsoever and the long-term projections would show huge surpluses rather than deficits. Readers of an article that purports to give the view of experts should know this information.

The Washington Post long ago ended the separation of its news and editorial departments, therefore it was not surprising to see the page three article complaining that “experts” are worried that the rhetoric of the presidential campaign will make it harder to find a “solution” for Medicare. As is standard practice, the Post’s corral of experts were exclusively people who largely agree with its editorial position on Medicare: that there have to be large cuts to the program.

The three people presented as experts in the piece are Robert Bixby, the executive director of the Peter Peterson funded Concord Coalition, Steve Bell, economic policy director at the Peter Peterson funded Bipartisan Policy Center and a former Republican congressional staffer, Dougas Holtz-Eakin, a former director of the Congressional Budget Office and the top economic advisor to John McCain in his 2008 campaign. All three present views of Medicare and budget deficits that are very similar to the views expressed in the Post editorials.

It would have been easy to find experts presenting a broader range of views if the Post had wanted to write this piece as a real news story. For example, they could have spoken to Henry Aaron at the Brookings Institution who has written extensively on health care policy for decades. Or, they could have talked to M.I.T. economist Jon Gruber who played a central role in designing both Governor Romney’s health care plan for Massachusetts and President Obama’s health care plan.

A broader group of experts could have explained to readers that most of Medicare’s projected shortfall has already been eliminated by the cost control measures that President Obama put in place in the Affordable Care Act. The projected shortfall over 75 years fell from 3.88 percent of taxable payroll in the 2009 Medicare Trustees Report to 1.35 percent of taxable payroll in the 2012 Medicare Trustees Report. The experts the Post relied upon apparently neglected to mention the sharp reduction in the projected deficit as a result of President Obama’s policies.

A broader group of experts might also have reminded Post readers that the underlying problem is not the cost of Medicare but rather the cost of health care more generally in the United States. If we paid the same amount per person as people in any other wealthy country, there would be no Medicare problem whatsoever and the long-term projections would show huge surpluses rather than deficits. Readers of an article that purports to give the view of experts should know this information.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a Washington Post column today, Kevin Hassett and Glenn Hubbard, two of the top economists on Governor Romney’s economic team, rightly take President Obama to task for blaming the weakness of the economy since the downturn on the financial crisis. They cite a recent study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland as showing that recoveries following financial crises tend to be stronger not weaker than other recoveries.

While there are some questions that can be raised about this study (was the financial crisis in the 1990 recession really comparable to what we saw in the fall of 2008?) the basic point seems right. After all, we do know how to set an economy in motion again following a financial crisis. Argentina managed to regain all the ground lost after a complete financial meltdown in December of 2001 in just 1.5 years. Our financial policy crew can’t be that much less competent than the folks calling the shots in Argentina. The idea that a financial crisis puts a mysterious curse on an economy was always more than a bit suspect.

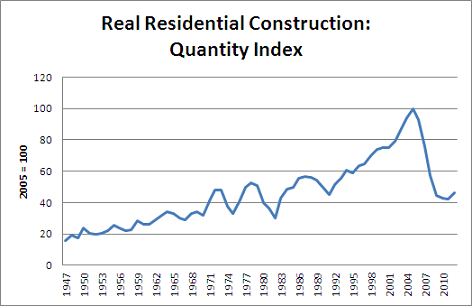

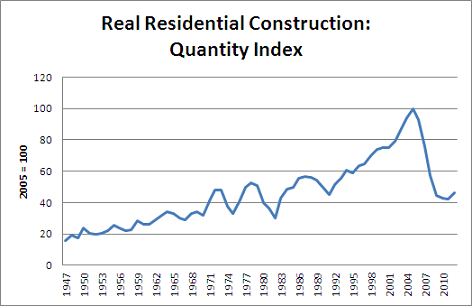

However the Cleveland Fed study doesn’t quite say that this recovery should be like any other recovery, as Hassett and Hubbard imply. The study goes on to note the extraordinary weakness in housing in this recovery and point out that this weakness could explain much of the weakness of the recovery.

While the study notes that there are questions of causation (a weak recovery could lead to weakness in housing), there can be little doubt that if residential construction had returned to its pre-recession level, as had been the case by this point in all prior post-war recoveries, the economy would be back near full employment.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Of course it is not hard to understand why housing has not recovered. The massive over-building of housing during the bubble years lead to an enormous over-supply of housing, which shows up in the data as a record vacancy rate in the years 2006-10. In the last couple of years the vacancy rate has begun to decline which can explain the recent uptick in housing over the last few quarters.

This housing story explains why we should have expected a long and drawn out recovery. There is no easy way to replace the massive loss in demand associated with the collapse of the housing sector. And, it is hard to blame the collapse on President Obama, since the overbuilding took place in the years 2000-2006 and the collapse was already well underway at the point where he took office.

The housing story also puts a kink in the three phases of stimulus story that Hassett and Hubbard outline, where the stimulus becomes contractionary when it is withdrawn after a short initial boost, and then slows the economy further after recovery as a result of a higher future tax burdens. The implication of the housing crash story is that we didn’t want a short initial boost, but rather needed a longer term stimulus that could sustain demand until some other component of consumption could fill the gap.

Obviously Hassett and Hubbard want us to believe that additional investment from the tax cuts proposed by Governor Romney would do the trick, however there is little evidence to believe that they would make much difference. With investment in equipment and software already pretty much back to its pre-recession share of GDP, we would have to see an unprecedented explosion in this category of investment to come close to making up the gap created by the falloff in residential construction. That doesn’t seem likely.

Ultimately we will need an increase in foreign demand, meaning a lower trade deficit, to fill the gap. This will require a lower valued dollar which will make U.S. goods more competitive internationally. Unfortunately, neither candidate seems willing to make the case for a lower valued dollar, which means that we can probably expect a weak economy for many years into the future, regardless of who gets elected.

In a Washington Post column today, Kevin Hassett and Glenn Hubbard, two of the top economists on Governor Romney’s economic team, rightly take President Obama to task for blaming the weakness of the economy since the downturn on the financial crisis. They cite a recent study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland as showing that recoveries following financial crises tend to be stronger not weaker than other recoveries.

While there are some questions that can be raised about this study (was the financial crisis in the 1990 recession really comparable to what we saw in the fall of 2008?) the basic point seems right. After all, we do know how to set an economy in motion again following a financial crisis. Argentina managed to regain all the ground lost after a complete financial meltdown in December of 2001 in just 1.5 years. Our financial policy crew can’t be that much less competent than the folks calling the shots in Argentina. The idea that a financial crisis puts a mysterious curse on an economy was always more than a bit suspect.

However the Cleveland Fed study doesn’t quite say that this recovery should be like any other recovery, as Hassett and Hubbard imply. The study goes on to note the extraordinary weakness in housing in this recovery and point out that this weakness could explain much of the weakness of the recovery.

While the study notes that there are questions of causation (a weak recovery could lead to weakness in housing), there can be little doubt that if residential construction had returned to its pre-recession level, as had been the case by this point in all prior post-war recoveries, the economy would be back near full employment.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Of course it is not hard to understand why housing has not recovered. The massive over-building of housing during the bubble years lead to an enormous over-supply of housing, which shows up in the data as a record vacancy rate in the years 2006-10. In the last couple of years the vacancy rate has begun to decline which can explain the recent uptick in housing over the last few quarters.

This housing story explains why we should have expected a long and drawn out recovery. There is no easy way to replace the massive loss in demand associated with the collapse of the housing sector. And, it is hard to blame the collapse on President Obama, since the overbuilding took place in the years 2000-2006 and the collapse was already well underway at the point where he took office.

The housing story also puts a kink in the three phases of stimulus story that Hassett and Hubbard outline, where the stimulus becomes contractionary when it is withdrawn after a short initial boost, and then slows the economy further after recovery as a result of a higher future tax burdens. The implication of the housing crash story is that we didn’t want a short initial boost, but rather needed a longer term stimulus that could sustain demand until some other component of consumption could fill the gap.

Obviously Hassett and Hubbard want us to believe that additional investment from the tax cuts proposed by Governor Romney would do the trick, however there is little evidence to believe that they would make much difference. With investment in equipment and software already pretty much back to its pre-recession share of GDP, we would have to see an unprecedented explosion in this category of investment to come close to making up the gap created by the falloff in residential construction. That doesn’t seem likely.

Ultimately we will need an increase in foreign demand, meaning a lower trade deficit, to fill the gap. This will require a lower valued dollar which will make U.S. goods more competitive internationally. Unfortunately, neither candidate seems willing to make the case for a lower valued dollar, which means that we can probably expect a weak economy for many years into the future, regardless of who gets elected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is popular among Washington elite types to tut-tut criticisms of the plan put forward by Representative Ryan and the Republicans to replace Medicare with a voucher program by claiming that “at least he has a plan.” This is supposed to be in contrast to President Obama and the Democrats who have no plan to deal with Medicare’s projected shortfall.

It’s possible that these Washington insiders missed it, but President Obama and the Democrats pushed through a piece of legislation called the “Affordable Care Act.” This bill proposes a number of mechanisms for containing costs within the Medicare program. As a result the projected shortfall has fallen by almost two-thirds, from 3.88 percent of taxable payroll in the 2009 Medicare Trustees Report to 1.35 percent of taxable payroll in the 2012 Medicare Trustees Report.

People can criticize the mechanisms the ACA put in place or complain that they did not go far enough, but to claim that President Obama and the Democrats did nothing to address the projected shortfall in Medicare is not true.

It is popular among Washington elite types to tut-tut criticisms of the plan put forward by Representative Ryan and the Republicans to replace Medicare with a voucher program by claiming that “at least he has a plan.” This is supposed to be in contrast to President Obama and the Democrats who have no plan to deal with Medicare’s projected shortfall.

It’s possible that these Washington insiders missed it, but President Obama and the Democrats pushed through a piece of legislation called the “Affordable Care Act.” This bill proposes a number of mechanisms for containing costs within the Medicare program. As a result the projected shortfall has fallen by almost two-thirds, from 3.88 percent of taxable payroll in the 2009 Medicare Trustees Report to 1.35 percent of taxable payroll in the 2012 Medicare Trustees Report.

People can criticize the mechanisms the ACA put in place or complain that they did not go far enough, but to claim that President Obama and the Democrats did nothing to address the projected shortfall in Medicare is not true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting article on the growth of high-speed trading on U.S. stock exchanges. While the piece notes the risks that these trading system can pose to long-term investor by taking profitable opportunities ahead of them, it reports the industry’s claim that it benefits long-term investors:

“The new trading sites and high-speed trading firms have managed to fend off critics by pointing to benefits that long-term investors have derived from the sophisticated markets.

One of the most popular ways to gauge how investors are doing is the difference between the price at which a stock can be bought and sold at a given moment — the so-called bid-ask spread. When this goes down, day traders, mutual funds and other institutional investors pay less to move in and out of stocks.”

While long-term investors in principle benefit from lower transactions costs, if these costs are offset by increased trading then there may be little or no gain to the investor. For example, if the average price of selling a share of stock falls by 50 percent, but fund managers respond to the price decline by doubling the amount of trading they do, total trading costs to investors will be unchanged.

There is research on the response of trading volume to prices that suggests the ratio is close to 1, meaning that trading volume will typically rise by an amount that will roughly offset any decline in the cost of trading. This means that ordinary investors are likely to see little benefit from any decline in trading costs associated with high-speed trading.

The NYT had an interesting article on the growth of high-speed trading on U.S. stock exchanges. While the piece notes the risks that these trading system can pose to long-term investor by taking profitable opportunities ahead of them, it reports the industry’s claim that it benefits long-term investors:

“The new trading sites and high-speed trading firms have managed to fend off critics by pointing to benefits that long-term investors have derived from the sophisticated markets.

One of the most popular ways to gauge how investors are doing is the difference between the price at which a stock can be bought and sold at a given moment — the so-called bid-ask spread. When this goes down, day traders, mutual funds and other institutional investors pay less to move in and out of stocks.”

While long-term investors in principle benefit from lower transactions costs, if these costs are offset by increased trading then there may be little or no gain to the investor. For example, if the average price of selling a share of stock falls by 50 percent, but fund managers respond to the price decline by doubling the amount of trading they do, total trading costs to investors will be unchanged.

There is research on the response of trading volume to prices that suggests the ratio is close to 1, meaning that trading volume will typically rise by an amount that will roughly offset any decline in the cost of trading. This means that ordinary investors are likely to see little benefit from any decline in trading costs associated with high-speed trading.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article reporting on how the presidential campaigns plan to make Medicare an issue in Florida as they compete for older voters. At one point it quotes Ed Gillespie, a senior adviser to the Romney campaign:

“The fact is, we’re going to go on offense here. Because the president has raided the Medicare trust fund to the tune of $716 billion to pay for a massive expansion of government known as Obamacare.”

It would have been helpful to point out to readers that President Obama did not “raid” the Medicare trust fund. This concept literally has not meaning. The trust fund holds U.S. government bonds that correspond to the surplus it has accumulated over the years. President Obama did not default on these bonds, which means that he has not pulled any money out of the Medicare system.

The claim that President Obama “raided” the trust fund because he has proposed additional health care spending in other areas (including the elimination of the doughnut hole in the Medicare prescription drug benefit) is like claiming that a person’s checking account had been raided because the bank lent the money to a small business. This is the way a modern economy works.

Either Mr. Romney’s senior advisor is completely clueless about the way the economy works or he is deliberately misrepresenting President Obama’s actions. Either case would make an interesting news story.

The NYT had an article reporting on how the presidential campaigns plan to make Medicare an issue in Florida as they compete for older voters. At one point it quotes Ed Gillespie, a senior adviser to the Romney campaign:

“The fact is, we’re going to go on offense here. Because the president has raided the Medicare trust fund to the tune of $716 billion to pay for a massive expansion of government known as Obamacare.”

It would have been helpful to point out to readers that President Obama did not “raid” the Medicare trust fund. This concept literally has not meaning. The trust fund holds U.S. government bonds that correspond to the surplus it has accumulated over the years. President Obama did not default on these bonds, which means that he has not pulled any money out of the Medicare system.

The claim that President Obama “raided” the trust fund because he has proposed additional health care spending in other areas (including the elimination of the doughnut hole in the Medicare prescription drug benefit) is like claiming that a person’s checking account had been raided because the bank lent the money to a small business. This is the way a modern economy works.

Either Mr. Romney’s senior advisor is completely clueless about the way the economy works or he is deliberately misrepresenting President Obama’s actions. Either case would make an interesting news story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his NYT column this morning, Roger Cohen repeated a theme about the presidential race that the punditry is anxious to shove down the public’s throat:

“Saving Private Romney is going to involve an ideological battle — over the size of government, the extent of Americans’ obligations to one another, even the soul of the country — that is no less than the United States deserves.”

This is utter nonsense. In fact on the vast majority of issues affecting the well-being of typical Americans Governor Romney and President Obama agree. They both strongly support the policies that have shifted a vast amount of income and wealth from ordinary workers to the richest 1.0 percent over the last three decades. The difference is that President Obama has committed himself to policies where the arithmetic adds up; Governor Romney refuses to be bound in the same way.

The vast majority of the upward redistribution over the last three decades has been in before-tax income, not after-tax. This has come about through a coddled and bloated financial sector that relies on massive government subsidies in the form of “too-big-to-fail” insurance. It has been the result of a system of corporate governance in which directors get 6-figure payoffs to look the other way as the CEOs and other top management pilfer the company.

The upward redistribution was also the result of a trade policy that deliberately sought to put manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world while largely protecting highly paid doctors and lawyers from similar competition. And it is the result of a Federal Reserve Board policy that deliberately throws millions of workers out of work to put downward pressure on their wages, thereby keeping inflation below its target rate.

These and other policies are the real story about “the extent of Americans’ obligations to one another, even the soul of the country.” Unfortunately, there is no real choice offered to the public in this area since the position of the candidates on these issues is largely indistinguishable.

There is a difference in that President Obama has laid out tax and budget plans that add up, whereas Governor Romney and Representative Ryan have refused to do so. Romney and Ryan have promised reductions in tax rates that will be offset by the elimination of loopholes, but have not identified any loopholes for elimination. Since they have taken the special treatment of capital gains and dividends off the table, it is not even possible to make up for the revenue they would lose their tax cuts as was recently shown by the Tax Policy Center’s analysis. (Cohen wrongly implies that Ryan’s plan might leave the wealthy paying higher taxes by eliminating loopholes. Actually, most would be paying close to zero tax since he proposes eliminating the tax on capital gains and dividends.)

The other place in which Romney-Ryan show their disdain for arithmetic is with their long-term budget plan. The Congressional Budget Office shows that the Ryan plan, which Romney has embraced, would zero out everything in the federal budget except Social Security, health care and defense after 2040. Presumably, Romney and Ryan don’t really intend to shut down the State Department, the border patrol, the federal court system and all the other areas that would get zero funding under their plan, but that is the implication of their budget.

In short, the real choice in this election is not about values, those are pretty much the same between the candidates. They both favor the rigging of the rules to the benefit of the wealthy. The difference is that President Obama is prepared to accept that laws of arithmetic are binding whereas Romney-Ryan refused to be similarly restricted in their policy proposals.

In his NYT column this morning, Roger Cohen repeated a theme about the presidential race that the punditry is anxious to shove down the public’s throat:

“Saving Private Romney is going to involve an ideological battle — over the size of government, the extent of Americans’ obligations to one another, even the soul of the country — that is no less than the United States deserves.”

This is utter nonsense. In fact on the vast majority of issues affecting the well-being of typical Americans Governor Romney and President Obama agree. They both strongly support the policies that have shifted a vast amount of income and wealth from ordinary workers to the richest 1.0 percent over the last three decades. The difference is that President Obama has committed himself to policies where the arithmetic adds up; Governor Romney refuses to be bound in the same way.

The vast majority of the upward redistribution over the last three decades has been in before-tax income, not after-tax. This has come about through a coddled and bloated financial sector that relies on massive government subsidies in the form of “too-big-to-fail” insurance. It has been the result of a system of corporate governance in which directors get 6-figure payoffs to look the other way as the CEOs and other top management pilfer the company.

The upward redistribution was also the result of a trade policy that deliberately sought to put manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world while largely protecting highly paid doctors and lawyers from similar competition. And it is the result of a Federal Reserve Board policy that deliberately throws millions of workers out of work to put downward pressure on their wages, thereby keeping inflation below its target rate.

These and other policies are the real story about “the extent of Americans’ obligations to one another, even the soul of the country.” Unfortunately, there is no real choice offered to the public in this area since the position of the candidates on these issues is largely indistinguishable.

There is a difference in that President Obama has laid out tax and budget plans that add up, whereas Governor Romney and Representative Ryan have refused to do so. Romney and Ryan have promised reductions in tax rates that will be offset by the elimination of loopholes, but have not identified any loopholes for elimination. Since they have taken the special treatment of capital gains and dividends off the table, it is not even possible to make up for the revenue they would lose their tax cuts as was recently shown by the Tax Policy Center’s analysis. (Cohen wrongly implies that Ryan’s plan might leave the wealthy paying higher taxes by eliminating loopholes. Actually, most would be paying close to zero tax since he proposes eliminating the tax on capital gains and dividends.)

The other place in which Romney-Ryan show their disdain for arithmetic is with their long-term budget plan. The Congressional Budget Office shows that the Ryan plan, which Romney has embraced, would zero out everything in the federal budget except Social Security, health care and defense after 2040. Presumably, Romney and Ryan don’t really intend to shut down the State Department, the border patrol, the federal court system and all the other areas that would get zero funding under their plan, but that is the implication of their budget.

In short, the real choice in this election is not about values, those are pretty much the same between the candidates. They both favor the rigging of the rules to the benefit of the wealthy. The difference is that President Obama is prepared to accept that laws of arithmetic are binding whereas Romney-Ryan refused to be similarly restricted in their policy proposals.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post continued its war on Social Security and Medicare today with a column by Charles Lane that told readers that seniors are wealthy because they have enough money (almost) to pay off their mortgage. No, I’m not kidding.

Lane wrote:

“Last year, the Pew Charitable Trusts reported that the median net worth of households headed by an adult 65 or older rose 42 percent in real terms between 1984 and 2009, to $170,494. During the same period, median net worth for households headed by an adult younger than 35 shrank 68 percent, to $3,662.”

Okay boys and girls, get out your pencil and paper. Net worth counts all the assets that seniors have. This means whatever money they have in 401(k)s or other retirement accounts, savings accounts, the value of their car and the equity in their home. The most recent data on existing home sales show that the price of the median home is now $189,400. This means that if the typical senior household cashed in their 401(k), emptied their saving and checking account and sold their car they would have almost enough money to pay off their mortgage. They would then be able to live rent and mortgage free, but would be entirely dependent on a Social Security check that averages a bit more than $1,200 a month. Yep, that’s the good life. Oh yeah, this is the median, half of seniors have less money than this.

In case you’re wondering about the big gain in wealth since 1984, seniors were far more likely to have defined benefit pensions in 1984 than in 2009. Defined benefit pensions are not factored into this wealth figure.

In his crusade against Medicare and Social Security Lane even gets the poverty data that he cites in his piece wrong. He told readers:

“The elderly poverty rate is higher under a different statistical definition designed to reflect seniors’ greater out-of-pocket medical costs, but it still remains slightly below that of the general population.”

There are no fact-checkers when the Washington Post decides to bash the elderly. The Census Bureau data show (Table 1) that the poverty rate for seniors under its alternative measure is 15.9 percent. That compares to 15.2 percent for the 18-64 population.

Just for fun, let’s look at the other side of Lane’s wealth story, the 68 percent drop in wealth among people under age 35. This number implies that the median wealth for the under 35 group was around $11,400 in 1984, before the old-timers started stealing all their money. Let’s see, suppose that the average person under age 35 could expect to live another 55 years. This means that their stock of wealth in 1984 would give them about $200 a year to support themselves. Today they can just get a bit less than $70 a year from their $3,662.

Okay, the point of this is that wealth for people under age 35 doesn’t mean anything. What matters for people under age 35 are their career prospects. Do they have a decent job with health care and a pension, can they expect to see a rising income over time? In fact, this picture does not look good right now, but the villains here are people with names like Alan Greenspan and Robert Rubin, not retirees scraping by on their Social Security and Medicare.

Serious people do not use wealth as a measure of the well-being of young people, but Lane is not engaged in a serious discussion. This is about cutting Social Security and Medicare and facts and logic are not going to be allowed to stand in the way.

Correction: Charles Lane points out to me that the Census alternative measure of the poverty rate for all people (including children) is 16.0 percent, which is in fact slightly above the 15.9 percent rate for people over age 65.

The Washington Post continued its war on Social Security and Medicare today with a column by Charles Lane that told readers that seniors are wealthy because they have enough money (almost) to pay off their mortgage. No, I’m not kidding.

Lane wrote:

“Last year, the Pew Charitable Trusts reported that the median net worth of households headed by an adult 65 or older rose 42 percent in real terms between 1984 and 2009, to $170,494. During the same period, median net worth for households headed by an adult younger than 35 shrank 68 percent, to $3,662.”

Okay boys and girls, get out your pencil and paper. Net worth counts all the assets that seniors have. This means whatever money they have in 401(k)s or other retirement accounts, savings accounts, the value of their car and the equity in their home. The most recent data on existing home sales show that the price of the median home is now $189,400. This means that if the typical senior household cashed in their 401(k), emptied their saving and checking account and sold their car they would have almost enough money to pay off their mortgage. They would then be able to live rent and mortgage free, but would be entirely dependent on a Social Security check that averages a bit more than $1,200 a month. Yep, that’s the good life. Oh yeah, this is the median, half of seniors have less money than this.

In case you’re wondering about the big gain in wealth since 1984, seniors were far more likely to have defined benefit pensions in 1984 than in 2009. Defined benefit pensions are not factored into this wealth figure.

In his crusade against Medicare and Social Security Lane even gets the poverty data that he cites in his piece wrong. He told readers:

“The elderly poverty rate is higher under a different statistical definition designed to reflect seniors’ greater out-of-pocket medical costs, but it still remains slightly below that of the general population.”

There are no fact-checkers when the Washington Post decides to bash the elderly. The Census Bureau data show (Table 1) that the poverty rate for seniors under its alternative measure is 15.9 percent. That compares to 15.2 percent for the 18-64 population.

Just for fun, let’s look at the other side of Lane’s wealth story, the 68 percent drop in wealth among people under age 35. This number implies that the median wealth for the under 35 group was around $11,400 in 1984, before the old-timers started stealing all their money. Let’s see, suppose that the average person under age 35 could expect to live another 55 years. This means that their stock of wealth in 1984 would give them about $200 a year to support themselves. Today they can just get a bit less than $70 a year from their $3,662.

Okay, the point of this is that wealth for people under age 35 doesn’t mean anything. What matters for people under age 35 are their career prospects. Do they have a decent job with health care and a pension, can they expect to see a rising income over time? In fact, this picture does not look good right now, but the villains here are people with names like Alan Greenspan and Robert Rubin, not retirees scraping by on their Social Security and Medicare.

Serious people do not use wealth as a measure of the well-being of young people, but Lane is not engaged in a serious discussion. This is about cutting Social Security and Medicare and facts and logic are not going to be allowed to stand in the way.

Correction: Charles Lane points out to me that the Census alternative measure of the poverty rate for all people (including children) is 16.0 percent, which is in fact slightly above the 15.9 percent rate for people over age 65.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Associated Press decided to use a “Fact Check” to wrongly tell readers that Social Security adds to the budget deficit. The piece acts as though Social Security’s impact on the budget is somewhat mysterious, with supporters of the program, like Representative Xavier Becerra and Senator Bernie Sanders, being confused into thinking that the program doesn’t add to the deficit, even though it really does.

There actually is not much mystery here to those familiar with government budget documents. There are two different measures of the deficit. There is the unified budget deficit, which adds in the payroll taxes collected for Social Security, just like any other source of revenue, and treats the benefits paid out by Social Security just like any other expenditure. In this measure, Social Security will add to the deficit in any year in which its benefit payments exceed its tax collections. (This is the case, even if the fund still has a surplus due to the interest it collects on the government bonds it holds, although it means that Social Security is contributing to the deficit because it is spending some of the interest it has earned.)

However there is also the on-budget deficit, which reflects the fact that Social Security is not supposed to be counted as part of the budget. This mysterious budget can be found in just about every single budget document the government publishes (e.g. here, Summary Table 1), saving arithmetically challenged reporters the need to subtract out Social Security taxes and spending from the unified budget. (The on-budget deficit also corresponds to the debt subject to the legal limit, which has played such a prominent role recently.)

Under the law, Social Security cannot possibly contribute to the on-budget deficit. It can only spend money that has been collected from the designated payroll tax or from the investment of past surpluses. (The money from general revenue to make up for the temporary payroll tax cut the last two years is an exception to this rule.) If benefit payments exceed current revenue and the money available in the trust fund, as the Congressional Budget Office projects will happen in 2038, then Social Security would not be able to pay full scheduled benefits. It could not force the government to increase its deficit.

It is incredible that a “fact check” failed to note the on-budget budget. This is obviously what Becerra and Sanders were referring to when they said that Social Security does not contribute to the deficit. Reporters who write on Social Security should be familiar with it.

This fact check also included some gratuitous editorializing on the deficit. It told readers:

“The issue [whether Social Security contributes to the deficit] is important because the federal government’s annual deficit already exceeds $1 trillion, making any more borrowing tough to swallow.”

It is not clear why the article considers more borrowing difficult to swallow. The financial markets have a very different view since investors are willing to lend the U.S. government money at extremely low interest rates. The reason why the government is running large deficits is because private sector spending plunged following the collapse of the housing bubble. Those who want to see the economy grow more rapidly are likely to prefer more government spending and larger deficits, since there is no other way to make up the shortfall in demand. Associated Press should leave editorializing like this in its opinion pieces.

Associated Press decided to use a “Fact Check” to wrongly tell readers that Social Security adds to the budget deficit. The piece acts as though Social Security’s impact on the budget is somewhat mysterious, with supporters of the program, like Representative Xavier Becerra and Senator Bernie Sanders, being confused into thinking that the program doesn’t add to the deficit, even though it really does.

There actually is not much mystery here to those familiar with government budget documents. There are two different measures of the deficit. There is the unified budget deficit, which adds in the payroll taxes collected for Social Security, just like any other source of revenue, and treats the benefits paid out by Social Security just like any other expenditure. In this measure, Social Security will add to the deficit in any year in which its benefit payments exceed its tax collections. (This is the case, even if the fund still has a surplus due to the interest it collects on the government bonds it holds, although it means that Social Security is contributing to the deficit because it is spending some of the interest it has earned.)

However there is also the on-budget deficit, which reflects the fact that Social Security is not supposed to be counted as part of the budget. This mysterious budget can be found in just about every single budget document the government publishes (e.g. here, Summary Table 1), saving arithmetically challenged reporters the need to subtract out Social Security taxes and spending from the unified budget. (The on-budget deficit also corresponds to the debt subject to the legal limit, which has played such a prominent role recently.)

Under the law, Social Security cannot possibly contribute to the on-budget deficit. It can only spend money that has been collected from the designated payroll tax or from the investment of past surpluses. (The money from general revenue to make up for the temporary payroll tax cut the last two years is an exception to this rule.) If benefit payments exceed current revenue and the money available in the trust fund, as the Congressional Budget Office projects will happen in 2038, then Social Security would not be able to pay full scheduled benefits. It could not force the government to increase its deficit.

It is incredible that a “fact check” failed to note the on-budget budget. This is obviously what Becerra and Sanders were referring to when they said that Social Security does not contribute to the deficit. Reporters who write on Social Security should be familiar with it.

This fact check also included some gratuitous editorializing on the deficit. It told readers:

“The issue [whether Social Security contributes to the deficit] is important because the federal government’s annual deficit already exceeds $1 trillion, making any more borrowing tough to swallow.”

It is not clear why the article considers more borrowing difficult to swallow. The financial markets have a very different view since investors are willing to lend the U.S. government money at extremely low interest rates. The reason why the government is running large deficits is because private sector spending plunged following the collapse of the housing bubble. Those who want to see the economy grow more rapidly are likely to prefer more government spending and larger deficits, since there is no other way to make up the shortfall in demand. Associated Press should leave editorializing like this in its opinion pieces.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión