Washington Post readers must be wondering after reading an article on a settlement by Abbott labs in a case brought by the Justice Department over promoting its drugs for off-label uses, in which Abbott agreed to pay $1.6 billion. The issue is that the Food and Drug Administration determines the acceptable uses for a drug. While doctors are allowed to prescribe drugs for other uses, the manufacturers are not allowed to promote their own drugs for “off-label” uses.

The Justice Department apparently had compelling evidence that Abbott had promoted off-label uses of its drug Depakote, a drug that was being improperly promoted as a sedative for elderly patients in nursing homes, according to the article. Such off-label promotions are a common, even if illegal, practice as the article notes.

The reason that drug companies violate the law and promote their drugs for unapproved uses is the huge patent rents that they are able to earn as a result of the patent monopolies granted by the government. Generic drug companies do not engage in the same sort of practices because they don’t have the incentive.

It would have been worth mentioning patent monopolies since they are central to the story. This sort of abuse is one reason that people are interested in promoting more efficient alternatives to patents for financing drug development.

Washington Post readers must be wondering after reading an article on a settlement by Abbott labs in a case brought by the Justice Department over promoting its drugs for off-label uses, in which Abbott agreed to pay $1.6 billion. The issue is that the Food and Drug Administration determines the acceptable uses for a drug. While doctors are allowed to prescribe drugs for other uses, the manufacturers are not allowed to promote their own drugs for “off-label” uses.

The Justice Department apparently had compelling evidence that Abbott had promoted off-label uses of its drug Depakote, a drug that was being improperly promoted as a sedative for elderly patients in nursing homes, according to the article. Such off-label promotions are a common, even if illegal, practice as the article notes.

The reason that drug companies violate the law and promote their drugs for unapproved uses is the huge patent rents that they are able to earn as a result of the patent monopolies granted by the government. Generic drug companies do not engage in the same sort of practices because they don’t have the incentive.

It would have been worth mentioning patent monopolies since they are central to the story. This sort of abuse is one reason that people are interested in promoting more efficient alternatives to patents for financing drug development.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson had a serious discussion of Paul Krugman’s idea (and in his professor days, Ben Bernanke‘s) that the Fed could boost demand by deliberately targeting a higher rate of inflation. The idea is that this would lead to a lower real interest rate.

If businesses expected inflation to be 4.0 percent over the next five years, rather than 2.0 percent, it would give them more incentive to invest. They would be able to sell everything for 20 percent more money in five years. Higher inflation would also erode the debt burden of homeowners and others with large debts. This could free up additional money for consumption.

While Samuelson acknowledges the potential benefits from higher inflation in boosting growth he still opposes the policy. He cites Bernanke’s own objection as Fed chair, that it could undermine the inflation-fighting credibility of the Fed in the future. He also adds his own objections:

1) wages might not keep pace with inflation, dampening purchasing power;

2) higher inflation may lead consumers to become fearful and therefore save rather than consume;

3) financial markets might over-react and demand higher real interest rates.

There is some validity to each of these, but it is likely that the negative effects would be dwarfed by the potential gains in a context of continued high unemployment. In the case of the Fed’s inflation fighting credibility, that might be nice, but we are losing over $1 trillion in output a year because of the continuing downturn. Millions of unemployed workers and their families are seeing their lives ruined. It is hard to imagine a loss of Fed credibility that can be remotely equal in cost.

As far as wages keeping up with inflation, we have a long history on this. In general they do, there is not a negative relationship between real wages and inflation. Of course, everyone’s wages will not keep pace with inflation. They will be losers in this story. But anyone who thinks they have a policy that will lead to large gains without hurting anyone has not studied their policy closely enough. (Many of the workers who would see real wage cuts with higher inflation would have lost their jobs if inflation had remained lower.)

Samuelson’s argument that consumers will become fearful seems unlikely in an environment of 4-5 percent inflation. This could happen if we see the sort of double-digit inflation that we saw in the 70s. Although even then consumers were not that fearful — economists like Martin Feldstein were still complaining about insufficient savings.

The same argument applies to the point about the interest rates demanded by investors, with the additional provision that the Fed can insure a supply of low interest loans to potential investors through its zero interest federal funds rate and its quantitative easing policies. While this may imply some greater risk premium associated with loans at some point in the future, that would again seem a minor concern in the current context.

Anyhow, it is refreshing to see Samuelson trying to engage seriously on this topic and to put his concerns on the table. I think he is mistaken, but this is the debate that we should be having.

Robert Samuelson had a serious discussion of Paul Krugman’s idea (and in his professor days, Ben Bernanke‘s) that the Fed could boost demand by deliberately targeting a higher rate of inflation. The idea is that this would lead to a lower real interest rate.

If businesses expected inflation to be 4.0 percent over the next five years, rather than 2.0 percent, it would give them more incentive to invest. They would be able to sell everything for 20 percent more money in five years. Higher inflation would also erode the debt burden of homeowners and others with large debts. This could free up additional money for consumption.

While Samuelson acknowledges the potential benefits from higher inflation in boosting growth he still opposes the policy. He cites Bernanke’s own objection as Fed chair, that it could undermine the inflation-fighting credibility of the Fed in the future. He also adds his own objections:

1) wages might not keep pace with inflation, dampening purchasing power;

2) higher inflation may lead consumers to become fearful and therefore save rather than consume;

3) financial markets might over-react and demand higher real interest rates.

There is some validity to each of these, but it is likely that the negative effects would be dwarfed by the potential gains in a context of continued high unemployment. In the case of the Fed’s inflation fighting credibility, that might be nice, but we are losing over $1 trillion in output a year because of the continuing downturn. Millions of unemployed workers and their families are seeing their lives ruined. It is hard to imagine a loss of Fed credibility that can be remotely equal in cost.

As far as wages keeping up with inflation, we have a long history on this. In general they do, there is not a negative relationship between real wages and inflation. Of course, everyone’s wages will not keep pace with inflation. They will be losers in this story. But anyone who thinks they have a policy that will lead to large gains without hurting anyone has not studied their policy closely enough. (Many of the workers who would see real wage cuts with higher inflation would have lost their jobs if inflation had remained lower.)

Samuelson’s argument that consumers will become fearful seems unlikely in an environment of 4-5 percent inflation. This could happen if we see the sort of double-digit inflation that we saw in the 70s. Although even then consumers were not that fearful — economists like Martin Feldstein were still complaining about insufficient savings.

The same argument applies to the point about the interest rates demanded by investors, with the additional provision that the Fed can insure a supply of low interest loans to potential investors through its zero interest federal funds rate and its quantitative easing policies. While this may imply some greater risk premium associated with loans at some point in the future, that would again seem a minor concern in the current context.

Anyhow, it is refreshing to see Samuelson trying to engage seriously on this topic and to put his concerns on the table. I think he is mistaken, but this is the debate that we should be having.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Just when you thought that the Washington Post could not go any further in bringing its readers off-the-wall statements from self-imagined great thinkers, it rises to the occasion. Today we have Ian Bremmer, the president of the Eurasia Group, giving us “five myths about America’s decline.”

This short piece contains heaping doses of silliness. For example, Bremmer thinks China will be suffering because:

“the ratio of Chinese workers to retirees is around 6 to 1 today, but by 2040, that number is expected to shrink to 2 to 1.” Fans of arithmetic know that this is not likely to pose a problem. Even with a substantial slowdown in the rate of productivity growth in China, the average worker is likely to be close to 4 times as productive in 2040 as they are today. This means that China will easily be able to accommodate substantial increases in living standards for both workers and retirees. In fact, the slowing of China’s population growth will provide enormous environmental benefits to China and the world long into the future.

There are other quirky comments and confused assertions which I’ll skip, but here’s the money quote:

“Finally, imagine a world in which a poorer country such as China becomes the world’s largest economy. The Chinese government’s willingness to lead on issues such as climate change and nuclear non-proliferation would probably pale in comparison with the leadership America provides today — yet one more reason Beijing will not supplant Washington anytime soon.”

Yes, that is an accurate quote. Bremmer thinks the world needs the United States’ leadership in dealing with global warming.

Just in case you have not been able to get news for the last 15 years (stranded in Antarctica or on some Pacific island without Internet access), the United States has been the most important force blocking any action to restrict greenhouse gas emissions. The most progress the world has ever made in this area was when George W. Bush explicitly said that the United States was not interested in taking part in the Kyoto Agreement. This allowed the other wealthy countries to move forward with a plan involving binding caps on emissions. The world would do much better without the sort of “leadership” that the United States has been showing in this area.

Just when you thought that the Washington Post could not go any further in bringing its readers off-the-wall statements from self-imagined great thinkers, it rises to the occasion. Today we have Ian Bremmer, the president of the Eurasia Group, giving us “five myths about America’s decline.”

This short piece contains heaping doses of silliness. For example, Bremmer thinks China will be suffering because:

“the ratio of Chinese workers to retirees is around 6 to 1 today, but by 2040, that number is expected to shrink to 2 to 1.” Fans of arithmetic know that this is not likely to pose a problem. Even with a substantial slowdown in the rate of productivity growth in China, the average worker is likely to be close to 4 times as productive in 2040 as they are today. This means that China will easily be able to accommodate substantial increases in living standards for both workers and retirees. In fact, the slowing of China’s population growth will provide enormous environmental benefits to China and the world long into the future.

There are other quirky comments and confused assertions which I’ll skip, but here’s the money quote:

“Finally, imagine a world in which a poorer country such as China becomes the world’s largest economy. The Chinese government’s willingness to lead on issues such as climate change and nuclear non-proliferation would probably pale in comparison with the leadership America provides today — yet one more reason Beijing will not supplant Washington anytime soon.”

Yes, that is an accurate quote. Bremmer thinks the world needs the United States’ leadership in dealing with global warming.

Just in case you have not been able to get news for the last 15 years (stranded in Antarctica or on some Pacific island without Internet access), the United States has been the most important force blocking any action to restrict greenhouse gas emissions. The most progress the world has ever made in this area was when George W. Bush explicitly said that the United States was not interested in taking part in the Kyoto Agreement. This allowed the other wealthy countries to move forward with a plan involving binding caps on emissions. The world would do much better without the sort of “leadership” that the United States has been showing in this area.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

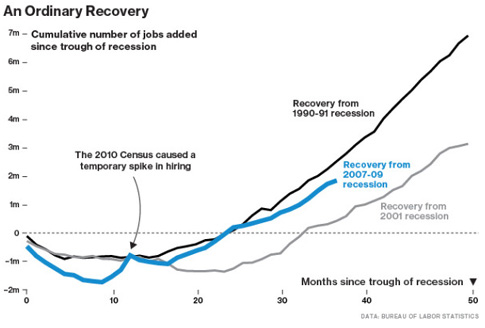

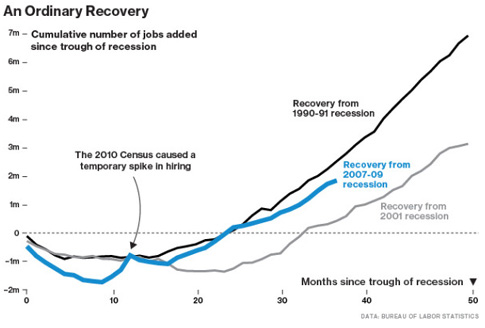

Peter Coy is ordinarily a pretty good reporter, but he really misses the boat with this chart, with the comment, “this jobs recovery is weak, all right, but right in line with the past two recoveries.”

When you evaluate the strength of a recovery, you also have to consider the depth of the downturn that preceded it. In the 1990-91 recession we lost 1.5 million jobs, in the 2001 recession we lost 1.6 million jobs. In the 2007-2009 recession we lost 7.5 million jobs.

The job loss in the downturn provides the room for job growth in the upturn. That is why the economy was able to generate 10.4 million jobs from June of 1975 to June of 1978 and 9.8 million jobs from December of 1982 to December of 1985. (Remember the labor force was less than 2/3rds the size of the current labor force.) In both cases, severe recessions left enormous room for job growth in the expansion. This is also true with the current downturn.

Several Obama supporters have picked up Coy’s graph and tried to make a political statement with it. They have. They don’t believe that Obama can make a serious economic case to support his re-election.

[Addendum: Apparently, this is not the first time they have tried this trick, as my colleague John Schmitt informs me.]

Peter Coy is ordinarily a pretty good reporter, but he really misses the boat with this chart, with the comment, “this jobs recovery is weak, all right, but right in line with the past two recoveries.”

When you evaluate the strength of a recovery, you also have to consider the depth of the downturn that preceded it. In the 1990-91 recession we lost 1.5 million jobs, in the 2001 recession we lost 1.6 million jobs. In the 2007-2009 recession we lost 7.5 million jobs.

The job loss in the downturn provides the room for job growth in the upturn. That is why the economy was able to generate 10.4 million jobs from June of 1975 to June of 1978 and 9.8 million jobs from December of 1982 to December of 1985. (Remember the labor force was less than 2/3rds the size of the current labor force.) In both cases, severe recessions left enormous room for job growth in the expansion. This is also true with the current downturn.

Several Obama supporters have picked up Coy’s graph and tried to make a political statement with it. They have. They don’t believe that Obama can make a serious economic case to support his re-election.

[Addendum: Apparently, this is not the first time they have tried this trick, as my colleague John Schmitt informs me.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition gave a Spanish economist, Pedro Videla, an opportunity to mislead listeners when he dismissed the idea of more public spending as a way out of the crisis by saying “overspending is what got Spaniards into this mess in the first place.”

This is wrong. Spain’s public sector was not overspending. In fact, Spain’s government was running large budget surpluses. NPR should try to find Spanish economists who are more familiar with Spain’s economy.

Morning Edition gave a Spanish economist, Pedro Videla, an opportunity to mislead listeners when he dismissed the idea of more public spending as a way out of the crisis by saying “overspending is what got Spaniards into this mess in the first place.”

This is wrong. Spain’s public sector was not overspending. In fact, Spain’s government was running large budget surpluses. NPR should try to find Spanish economists who are more familiar with Spain’s economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I really don’t like to beat up on Ben Bernanke. I don’t know him personally, but everyone I know who does says that he’s a really nice guy. And, there is no doubt he is a very smart economist. But he shares the blame for the downturn with his former boss, Alan Greenspan. Even worse, he still seems resistant to getting the story right.

He gave a speech last month in which he forgives himself and others in policy positions for being surprised by the dangers posed by the collapse of the housing bubble. He noted that we lost $10 trillion in wealth when the stock bubble collapsed and that was no big deal. Why should we have expected it to be a big deal when we lost $10 trillion in wealth when the housing bubble collapsed? He then goes on to comment on the wonders of bank leverage and financial crises.

Bernanke should know that both sides of his assertion are seriously misleading. First, the wealth lost in the stock crash was stock wealth. The wealth effect from consumer spending on stock wealth is generally estimated to be much lower than the wealth effect from housing wealth. The range from the former is typically estimated at 3-4 cents on the dollar, as opposed to 5-7 cents on the dollar from housing wealth.

Also, housing wealth has a much more direct effect on stimulating demand through construction than stock wealth has in boosting investment. Residential construction was more than 2.0-3.0 percentage points of GDP ($300-$450 billion a year in today’s economy) above its trend level at the peak of the bubble. By contrast, the investment generated by the stock bubble was no more than 1-2 percentage points of GDP.

More importantly, the loss of wealth from the stock bubble was temporary. If Bernanke consulted the data (Table L.213) that his organization publishes, he would notice that by March of 2004, the stock market had already recovered more than half of the value it had lost. Its valuation at that point was only a bit more than $4 trillion off its 2000 peak and was actually above the 1998 year-end level. Since no one spends based on daily movements in the stock market (i.e. there is a lag between when stock prices rise and when people adjust their spending), the negative wealth effect at that point would have been limited.

By contrast, housing wealth has continued to decline. We have now lost close to $8 trillion in real housing wealth compared to the bubble peak in 2006. And, there is no plausible story whereby housing wealth will come back quickly.

The other part of Bernanke’s story that is wrong is that the collapse of the stock bubble was no big deal for the economy. While the official recession was short and mild, lasting from March of 2001 to November of 2001, the economy continued to lose jobs through 2002 and didn’t start to create jobs again until September of 2003. This is shown clearly in the employment to population rate; data that I recall Bernanke citing in a talk in January of 2004 when he was explaining why it was necessary for the Fed to still keep the federal funds rate at the extraordinarily low level of 1.0 percent.

Employment-to-Population Ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The reason why this argument is important is that financial crisis can be complicated and mysterious. They are hidden in complex financial assets on balance sheets that almost no one sees.

By contrast, bubbles are simple. They sit there expanding in broad daylight. Could any sentient being miss the stock bubble or the housing bubble?

And, the demand gap created by their collapse is really straightforward. Residential construction is off by 4.0 percentage points of GDP as we deal with a badly overbuilt housing market. That’s $600 billion a year in lost demand. Consumption has also plunged, with the saving rate going from near zero at the peak of the bubble to 4-5 percent at present. That implies a loss in annual consumption demand of $400-500 billion. Add in another $200-$300 billion in lost demand due to the collapse of the bubble in non-residential real estate and the contraction of the state and local government sector in response to lost tax revenue and you have a gap in annual demand of $1.2-$1.4 trillion.

This is all very simple. The arithmetic we learn in third grade should cut it.

By contrast, what are the financial crisis promulgators talking about? I enjoyed the crisis as much as anyone, but what demand should we be seeing right now that we are not seeing because we had the financial crisis?

That is a real simple question that I would like to hear answered. Consumption is actually still unusually high relative to disposable income. The financial crisis cult thinks it should be higher, why?

Investment in equipment and software is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. That is very impressive given the large amounts of excess capacity in most sectors. Even non-residential construction has bounced back, in spite of the overbuilding in many sector due to the bubble.

In short, if the crisis cult has a story let’s hear it. If they don’t have a story, then Bernanke and his followers should look for another line of work.

I really don’t like to beat up on Ben Bernanke. I don’t know him personally, but everyone I know who does says that he’s a really nice guy. And, there is no doubt he is a very smart economist. But he shares the blame for the downturn with his former boss, Alan Greenspan. Even worse, he still seems resistant to getting the story right.

He gave a speech last month in which he forgives himself and others in policy positions for being surprised by the dangers posed by the collapse of the housing bubble. He noted that we lost $10 trillion in wealth when the stock bubble collapsed and that was no big deal. Why should we have expected it to be a big deal when we lost $10 trillion in wealth when the housing bubble collapsed? He then goes on to comment on the wonders of bank leverage and financial crises.

Bernanke should know that both sides of his assertion are seriously misleading. First, the wealth lost in the stock crash was stock wealth. The wealth effect from consumer spending on stock wealth is generally estimated to be much lower than the wealth effect from housing wealth. The range from the former is typically estimated at 3-4 cents on the dollar, as opposed to 5-7 cents on the dollar from housing wealth.

Also, housing wealth has a much more direct effect on stimulating demand through construction than stock wealth has in boosting investment. Residential construction was more than 2.0-3.0 percentage points of GDP ($300-$450 billion a year in today’s economy) above its trend level at the peak of the bubble. By contrast, the investment generated by the stock bubble was no more than 1-2 percentage points of GDP.

More importantly, the loss of wealth from the stock bubble was temporary. If Bernanke consulted the data (Table L.213) that his organization publishes, he would notice that by March of 2004, the stock market had already recovered more than half of the value it had lost. Its valuation at that point was only a bit more than $4 trillion off its 2000 peak and was actually above the 1998 year-end level. Since no one spends based on daily movements in the stock market (i.e. there is a lag between when stock prices rise and when people adjust their spending), the negative wealth effect at that point would have been limited.

By contrast, housing wealth has continued to decline. We have now lost close to $8 trillion in real housing wealth compared to the bubble peak in 2006. And, there is no plausible story whereby housing wealth will come back quickly.

The other part of Bernanke’s story that is wrong is that the collapse of the stock bubble was no big deal for the economy. While the official recession was short and mild, lasting from March of 2001 to November of 2001, the economy continued to lose jobs through 2002 and didn’t start to create jobs again until September of 2003. This is shown clearly in the employment to population rate; data that I recall Bernanke citing in a talk in January of 2004 when he was explaining why it was necessary for the Fed to still keep the federal funds rate at the extraordinarily low level of 1.0 percent.

Employment-to-Population Ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The reason why this argument is important is that financial crisis can be complicated and mysterious. They are hidden in complex financial assets on balance sheets that almost no one sees.

By contrast, bubbles are simple. They sit there expanding in broad daylight. Could any sentient being miss the stock bubble or the housing bubble?

And, the demand gap created by their collapse is really straightforward. Residential construction is off by 4.0 percentage points of GDP as we deal with a badly overbuilt housing market. That’s $600 billion a year in lost demand. Consumption has also plunged, with the saving rate going from near zero at the peak of the bubble to 4-5 percent at present. That implies a loss in annual consumption demand of $400-500 billion. Add in another $200-$300 billion in lost demand due to the collapse of the bubble in non-residential real estate and the contraction of the state and local government sector in response to lost tax revenue and you have a gap in annual demand of $1.2-$1.4 trillion.

This is all very simple. The arithmetic we learn in third grade should cut it.

By contrast, what are the financial crisis promulgators talking about? I enjoyed the crisis as much as anyone, but what demand should we be seeing right now that we are not seeing because we had the financial crisis?

That is a real simple question that I would like to hear answered. Consumption is actually still unusually high relative to disposable income. The financial crisis cult thinks it should be higher, why?

Investment in equipment and software is almost back to its pre-recession share of GDP. That is very impressive given the large amounts of excess capacity in most sectors. Even non-residential construction has bounced back, in spite of the overbuilding in many sector due to the bubble.

In short, if the crisis cult has a story let’s hear it. If they don’t have a story, then Bernanke and his followers should look for another line of work.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Outsourced to Mark Weisbrot.

The Economist’s editorial opinion on the second round of the French election is a bit unsubtle. The title “The rather dangerous Monsieur Hollande” and sub-head “The Socialist who is likely to be the next French president would be bad for his country and Europe” tell you all you might need to know about how the editors of this dull magazine really feel about the prospect of a left-of-center government in France.

To scare the readers, the editorial notes of this dangerous man that “By his own calculations, his proposals would splurge an extra €20 billion over five years. The state would grow even bigger.”

I asked our friend, Mr. Arithmetic, what he thought about this “splurge”. His answer was that “€20 billion is between one tenth and two tenths of one percent of France’s GDP over the next five years, according to the latest IMF projections.”

Mr. Arithmetic says that this isn’t much of a “splurge,” and that it will be hard for anyone to notice that the state is “even bigger.”

(Thanks to Anita Kirpalani for flagging the editorial).

Outsourced to Mark Weisbrot.

The Economist’s editorial opinion on the second round of the French election is a bit unsubtle. The title “The rather dangerous Monsieur Hollande” and sub-head “The Socialist who is likely to be the next French president would be bad for his country and Europe” tell you all you might need to know about how the editors of this dull magazine really feel about the prospect of a left-of-center government in France.

To scare the readers, the editorial notes of this dangerous man that “By his own calculations, his proposals would splurge an extra €20 billion over five years. The state would grow even bigger.”

I asked our friend, Mr. Arithmetic, what he thought about this “splurge”. His answer was that “€20 billion is between one tenth and two tenths of one percent of France’s GDP over the next five years, according to the latest IMF projections.”

Mr. Arithmetic says that this isn’t much of a “splurge,” and that it will be hard for anyone to notice that the state is “even bigger.”

(Thanks to Anita Kirpalani for flagging the editorial).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Adam Davidson has a piece in the Sunday NYT magazine on Mitt Romney’s former business partner, Edward Conard and his new book, Unintended Consequences. At one point, the piece cites me as saying that for each dollar earned by investors (corporations), the rest of society gets five dollars.

This should not sound surprising. This is simply the division of national income between capital and labor. The after-tax capital share of corporate income is roughly one-sixth of total income. This means that if GDP increases by $1 billion, then capital will typically get around $160 million, with the rest going to labor and corporate taxes.

Note that this does not mean that investors are responsible for this $1 billion increase in output. Their actions contributed to the growth of output in the same way as did the actions of workers and the government. The misleading part of the picture is Conard’s implication that if not for the heroic investor, none of this wealth would have been created.

In standard economic theory if one investor had not put money to use, then another one would have. The difference in output would have been trivial.

(I have a review of Conard’s book on Huffington Post.)

[Thanks to Arthur Munisteri for spelling correction.]

Adam Davidson has a piece in the Sunday NYT magazine on Mitt Romney’s former business partner, Edward Conard and his new book, Unintended Consequences. At one point, the piece cites me as saying that for each dollar earned by investors (corporations), the rest of society gets five dollars.

This should not sound surprising. This is simply the division of national income between capital and labor. The after-tax capital share of corporate income is roughly one-sixth of total income. This means that if GDP increases by $1 billion, then capital will typically get around $160 million, with the rest going to labor and corporate taxes.

Note that this does not mean that investors are responsible for this $1 billion increase in output. Their actions contributed to the growth of output in the same way as did the actions of workers and the government. The misleading part of the picture is Conard’s implication that if not for the heroic investor, none of this wealth would have been created.

In standard economic theory if one investor had not put money to use, then another one would have. The difference in output would have been trivial.

(I have a review of Conard’s book on Huffington Post.)

[Thanks to Arthur Munisteri for spelling correction.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eduardo Porter told readers in his Economic Scene column that because China’s trade surplus overall has fallen, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner:

“will have a harder time making the case that America’s trade deficit is somehow China’s fault.”

Actually, he will have no problem at all making the case that the U.S. trade deficit is the result of an over-valued dollar, which China helps to sustain by buying hundreds of billions of dollars of government bonds.

In a system of floating exchange rates, like the one we are supposed to have, trade imbalances are corrected through a decline in the value of the currencies of deficit nations, like the United States. The mechanism is that more dollars are being supplied to buy imports than are needed to purchase imports from the United States. This leads to an excess supply of dollars, which then causes the dollar to fall in value against other currencies. In a system of floating exchange rates an excess supply of dollars is supposed lead the dollar to fall in the same way that an excess supply of shoes is expected to cause the price of shoes to fall.

A lower valued dollar makes imports more expensive for people in the United States leading people to buy fewer imports. It also makes exports cheaper for people living in other countries, leading them to buy more U.S. exports. This process then continues until the trade balance adjusts.

By explicit policy China is preventing this process of adjustment. It has an explicit policy of pegging its currency against the dollar. This means that it buys as many dollars as necessary to maintain the peg. (This is done in broad daylight, it is not a mysterious process of “manipulation” that is done in secret.)

Therefore Geithner would have no problem at all making the case that America’s trade deficit is China’s fault, this is exactly what textbook economics maintains. (He likely will not want to make this case, since many media accounts have suggested that Geithner is more interested in directly pressing issues that will help businesses in the United States rather than addressing the trade imbalance, which would benefit millions of workers.)

It is also worth noting that standard economic theory predicts that fast growing developing countries like China will have a trade deficit, while slower growing wealthy countries like the United States will have a trade surplus. The argument is that capital is relatively scarce and gets a better return in China than in the United States. This means that the U.S. should be lending vast amounts of money to China, not the other way around.

Eduardo Porter told readers in his Economic Scene column that because China’s trade surplus overall has fallen, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner:

“will have a harder time making the case that America’s trade deficit is somehow China’s fault.”

Actually, he will have no problem at all making the case that the U.S. trade deficit is the result of an over-valued dollar, which China helps to sustain by buying hundreds of billions of dollars of government bonds.

In a system of floating exchange rates, like the one we are supposed to have, trade imbalances are corrected through a decline in the value of the currencies of deficit nations, like the United States. The mechanism is that more dollars are being supplied to buy imports than are needed to purchase imports from the United States. This leads to an excess supply of dollars, which then causes the dollar to fall in value against other currencies. In a system of floating exchange rates an excess supply of dollars is supposed lead the dollar to fall in the same way that an excess supply of shoes is expected to cause the price of shoes to fall.

A lower valued dollar makes imports more expensive for people in the United States leading people to buy fewer imports. It also makes exports cheaper for people living in other countries, leading them to buy more U.S. exports. This process then continues until the trade balance adjusts.

By explicit policy China is preventing this process of adjustment. It has an explicit policy of pegging its currency against the dollar. This means that it buys as many dollars as necessary to maintain the peg. (This is done in broad daylight, it is not a mysterious process of “manipulation” that is done in secret.)

Therefore Geithner would have no problem at all making the case that America’s trade deficit is China’s fault, this is exactly what textbook economics maintains. (He likely will not want to make this case, since many media accounts have suggested that Geithner is more interested in directly pressing issues that will help businesses in the United States rather than addressing the trade imbalance, which would benefit millions of workers.)

It is also worth noting that standard economic theory predicts that fast growing developing countries like China will have a trade deficit, while slower growing wealthy countries like the United States will have a trade surplus. The argument is that capital is relatively scarce and gets a better return in China than in the United States. This means that the U.S. should be lending vast amounts of money to China, not the other way around.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In reference to the high unemployment rate in Spain the Post told readers:

“The recession also is expected to force down wages and prices and, over time, make Spanish exports more competitive and the country more attractive to investors and tourists.”

Actually there are few, if any, examples of countries where high unemployment led to this process of falling wages and prices that in turn restored competitiveness. Wages tend to be very sticky downward, which is why prices in countries across the euro zone, even those with double-digit unemployment, continue to rise.

It’s also not clear these economies would benefit even if they did have deflation. This would make real interest rates higher (borrowers would have to repay loans in money that is worth more than what they borrowed) and also increase the interest burden for homeowners with mortgages and other debtors.

Many economists have made these points. It is therefore misleading readers to imply that there is a simple story whereby Spain’s high unemployment is a step in a process toward restoring prosperity.

In reference to the high unemployment rate in Spain the Post told readers:

“The recession also is expected to force down wages and prices and, over time, make Spanish exports more competitive and the country more attractive to investors and tourists.”

Actually there are few, if any, examples of countries where high unemployment led to this process of falling wages and prices that in turn restored competitiveness. Wages tend to be very sticky downward, which is why prices in countries across the euro zone, even those with double-digit unemployment, continue to rise.

It’s also not clear these economies would benefit even if they did have deflation. This would make real interest rates higher (borrowers would have to repay loans in money that is worth more than what they borrowed) and also increase the interest burden for homeowners with mortgages and other debtors.

Many economists have made these points. It is therefore misleading readers to imply that there is a simple story whereby Spain’s high unemployment is a step in a process toward restoring prosperity.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión