David Brooks is playing the “it’s all so confusing, we just can’t really know anything about economic policy” game. The point is to try to make it intellectually respectable to question whether stimulus spending can boost the economy.

This is important for the right, because the evidence from the austerity induced double-dip in the UK and euro zone is making it ever harder to deny that government spending can and does stimulate the economy just as the old textbook models predict. In the wake of this evidence, it is incredibly valuable that someone like Brooks, who can claim credibility by virtue of his perch on the NYT oped page, muddy the waters with this sort of “it’s all so confusing” piece.

The way to understand Brooks’ column, which is ostensibly about the difficulty of sorting out whether government policies work, but which is really about confusing the issue on stimulus, is to imagine that the topic was evolution or the orbit of the earth around the sun. If a person was committed to denying evolution they could easily point to all the mistakes that biologists had made over the years in constructing evolutionary paths. Similarly, one could deny that the earth orbits the sun by pointing to all the difficulties that astronomers encountered over the years in properly calculating its orbit. As Brooks would say, it’s all so confusing, it’s too bad that we don’t have some way to determine these issues.

Of course honest people know that we have ways to determine these issues and it has long been a settled issue that evolution explains the structure of the biological world and that the earth orbits the sun. Similarly, it is simply not true, as Brooks claims:

“Nearly 80 years later, it’s hard to know if the New Deal did much to end the Great Depression.”

Nor is it Brooks being honest in saying:

“Many esteemed and/or Nobel Prize-winning economists like Joseph Stiglitz, Larry Summers and Christina Romer argued that it would help lift the economy out of recession. ….

We went ahead and spent the roughly $800 billion. What have we learned?

For certain, nothing. The economists who supported the stimulus now argue the economy would have been worse off without it.”

At the time, Stiglitz, like most prominent progressive economists outside the administration, said as loudly as possible that the stimulus would not be large enough to lift the economy out of recession. (Here’s one of my pieces on the topic.) Romer also argued for the need for a much bigger stimulus in a private memo, which has been documented in memos that have since been made public. (Summers claims that he agreed with Romer’s position.)

To imply, as Brooks does, that events have somehow shown the advocates of stimulus as being wrong, or that there is even much grounds for questioning the argument for stimulus as its proponents laid it out at the time is an effort to muddy the waters pure and simple. There any number of studies that have shown the stimulus has worked pretty much as predicted, such as this one by the Congressional Budget Office and this one, using an entirely different methodology by two Dartmouth economists.

Of course there can be economists who are opposed to the idea that stimulus can work as an article of religious faith. Economic theory also predicts that for a large enough sum of money there will be economists who will say that the stimulus did not work regardless of what they actually believe to be true.

But the evidence on stimulus, like the evidence on evolution and the orbit of the earth, is not ambiguous. It is unfortunate that some people get paychecks for trying to mislead the public into thinking it is.

[btw, Brooks deserves a heaping dose of ridicule for this section:

“Businesses conduct hundreds of thousands of randomized trials each year. Pharmaceutical companies conduct thousands more. But government? Hardly any.”

If Brooks ever read the paper he writes for, he would know that the pharmaceutical industry routinely misrepresents the results of its studies to exaggerate the effectiveness of its drugs and conceal evidence of harmful side effects. Given its track record it is hard to difficult to believe that anyone could hold up the pharmaceutical industry as a model with a straight face.]

David Brooks is playing the “it’s all so confusing, we just can’t really know anything about economic policy” game. The point is to try to make it intellectually respectable to question whether stimulus spending can boost the economy.

This is important for the right, because the evidence from the austerity induced double-dip in the UK and euro zone is making it ever harder to deny that government spending can and does stimulate the economy just as the old textbook models predict. In the wake of this evidence, it is incredibly valuable that someone like Brooks, who can claim credibility by virtue of his perch on the NYT oped page, muddy the waters with this sort of “it’s all so confusing” piece.

The way to understand Brooks’ column, which is ostensibly about the difficulty of sorting out whether government policies work, but which is really about confusing the issue on stimulus, is to imagine that the topic was evolution or the orbit of the earth around the sun. If a person was committed to denying evolution they could easily point to all the mistakes that biologists had made over the years in constructing evolutionary paths. Similarly, one could deny that the earth orbits the sun by pointing to all the difficulties that astronomers encountered over the years in properly calculating its orbit. As Brooks would say, it’s all so confusing, it’s too bad that we don’t have some way to determine these issues.

Of course honest people know that we have ways to determine these issues and it has long been a settled issue that evolution explains the structure of the biological world and that the earth orbits the sun. Similarly, it is simply not true, as Brooks claims:

“Nearly 80 years later, it’s hard to know if the New Deal did much to end the Great Depression.”

Nor is it Brooks being honest in saying:

“Many esteemed and/or Nobel Prize-winning economists like Joseph Stiglitz, Larry Summers and Christina Romer argued that it would help lift the economy out of recession. ….

We went ahead and spent the roughly $800 billion. What have we learned?

For certain, nothing. The economists who supported the stimulus now argue the economy would have been worse off without it.”

At the time, Stiglitz, like most prominent progressive economists outside the administration, said as loudly as possible that the stimulus would not be large enough to lift the economy out of recession. (Here’s one of my pieces on the topic.) Romer also argued for the need for a much bigger stimulus in a private memo, which has been documented in memos that have since been made public. (Summers claims that he agreed with Romer’s position.)

To imply, as Brooks does, that events have somehow shown the advocates of stimulus as being wrong, or that there is even much grounds for questioning the argument for stimulus as its proponents laid it out at the time is an effort to muddy the waters pure and simple. There any number of studies that have shown the stimulus has worked pretty much as predicted, such as this one by the Congressional Budget Office and this one, using an entirely different methodology by two Dartmouth economists.

Of course there can be economists who are opposed to the idea that stimulus can work as an article of religious faith. Economic theory also predicts that for a large enough sum of money there will be economists who will say that the stimulus did not work regardless of what they actually believe to be true.

But the evidence on stimulus, like the evidence on evolution and the orbit of the earth, is not ambiguous. It is unfortunate that some people get paychecks for trying to mislead the public into thinking it is.

[btw, Brooks deserves a heaping dose of ridicule for this section:

“Businesses conduct hundreds of thousands of randomized trials each year. Pharmaceutical companies conduct thousands more. But government? Hardly any.”

If Brooks ever read the paper he writes for, he would know that the pharmaceutical industry routinely misrepresents the results of its studies to exaggerate the effectiveness of its drugs and conceal evidence of harmful side effects. Given its track record it is hard to difficult to believe that anyone could hold up the pharmaceutical industry as a model with a straight face.]

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Since folks have asked my thoughts (you had to ask?) on the Krugman-Bernanke debate, I will throw in my two cents. The question at hand is whether the Fed can plausible generate more inflation, and thereby lower real interest rates and reduce the unemployment rate by announcing a commitment to higher inflation rate over the near future. This could mean, for example, committing itself to 4 percent inflation over the next 5 years.

If this policy was successful, it would lead to lower real interest rates, which would in turn lead to more consumption and investment. Ideally we would also see a decline in th real value of the dollar, leading to more net exports, the essential long-term path to full employment.

My view is that this path would likely be successful, if the Fed were really committed to it. That means continually buying up vast amounts of assets if the inflation rate did not appear to be rising. This should ultimately freak enough investor types into thinking that Bernanke was sufficiently nuts that he could cause inflation. They would then hedge themselves against this risk by buying up all sorts of commodities to protect against inflation, which would then lead to inflation.

That looks like a pretty compelling story to me, but perhaps at least as important, I don’t see the downside. Bernanke’s obsession with the Fed’s inflation fighting credibility (like the ECB’s) is really pathetic. How much is this worth when you just wrecked an economy with your incompetence in protecting against asset bubbles?

Other things equal, it is better to have central banks that have some credibility in fighting inflation, but how does this compare against tens of millions of people in the U.S. and euro zone being unemployed? If the latter is such a small matter, would the inflation fighters volunteer to surrender their jobs so that some of the unemployed can work?

Finally, if buying up tons of assets will not cause inflation, then there is definitely no excuse not to do it. The Fed can hold $10 trillion in assets and pay the interest to the Treasury each year. Currently it is refunding about $80 billion a year to the Treasury from its interest in assets.

Suppose this was instead $400 billion a year or $4 trillion over a decade? That should make even the most ardent deficit hawk happy. There would be no deficit problem in that story, which would mean that we can freely spend on all sorts of things that can boost growth and help people. Tell me again that story about Fed credibility?

Since folks have asked my thoughts (you had to ask?) on the Krugman-Bernanke debate, I will throw in my two cents. The question at hand is whether the Fed can plausible generate more inflation, and thereby lower real interest rates and reduce the unemployment rate by announcing a commitment to higher inflation rate over the near future. This could mean, for example, committing itself to 4 percent inflation over the next 5 years.

If this policy was successful, it would lead to lower real interest rates, which would in turn lead to more consumption and investment. Ideally we would also see a decline in th real value of the dollar, leading to more net exports, the essential long-term path to full employment.

My view is that this path would likely be successful, if the Fed were really committed to it. That means continually buying up vast amounts of assets if the inflation rate did not appear to be rising. This should ultimately freak enough investor types into thinking that Bernanke was sufficiently nuts that he could cause inflation. They would then hedge themselves against this risk by buying up all sorts of commodities to protect against inflation, which would then lead to inflation.

That looks like a pretty compelling story to me, but perhaps at least as important, I don’t see the downside. Bernanke’s obsession with the Fed’s inflation fighting credibility (like the ECB’s) is really pathetic. How much is this worth when you just wrecked an economy with your incompetence in protecting against asset bubbles?

Other things equal, it is better to have central banks that have some credibility in fighting inflation, but how does this compare against tens of millions of people in the U.S. and euro zone being unemployed? If the latter is such a small matter, would the inflation fighters volunteer to surrender their jobs so that some of the unemployed can work?

Finally, if buying up tons of assets will not cause inflation, then there is definitely no excuse not to do it. The Fed can hold $10 trillion in assets and pay the interest to the Treasury each year. Currently it is refunding about $80 billion a year to the Treasury from its interest in assets.

Suppose this was instead $400 billion a year or $4 trillion over a decade? That should make even the most ardent deficit hawk happy. There would be no deficit problem in that story, which would mean that we can freely spend on all sorts of things that can boost growth and help people. Tell me again that story about Fed credibility?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m shorting Morgan Stanley after reading the NYT column on China by Ruchir Sharma, the head of emerging market equities at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. The piece begins by telling readers:

“more than half of Americans think China is already the world’s leading economy — an astonishing misperception, given that China’s gross domestic product is still less than half of America’s.”

That is not what our friends at the IMF say. On a purchasing power parity basis, which assigns the same set of prices to goods and services produced in both countries, China is already almost 80 percent of the size of the U.S. economy. There is also some serious research suggesting that because of mis-measurement of prices in rural areas, China’s economy is already larger than the U.S. economy.

The piece then goes on to tell us:

“It is well known that developing nations hit a “middle-income trap,” and stop catching up to rich nations, when per-capita income reaches about $5,000 to $15,000 (in current dollars). The examples (Brazil, Mexico, Malaysia) are numerous.”

Huh? This is well-known to whom? This is a huge range (imagine per capita GDP in the U.S. tripled to $150,000 per person) that includes almost 70 countries. It makes a huge difference whether a country’s growth slows near the bottom of this range, where they are still relatively poor, as opposed to the top, where they are decidedly middle class.

Furthermore, countries enter this range with radically different growth paths. The speedy growers like China are the exception. More typically countries edge up into this range with modest growth rates. In the more typical case, there is not much room for a slowdown. Of course in some of the fast growers, like Malaysia, one of Sharma’s examples of a slowdown country, there is little evidence of a slowdown as they maintain rapid growth right through this range.

Then Sharma tells us that China passed his $5,000 mark last year. Actually the IMF says it was 2007, and if the understatement view is right, China hit this mark as early as 2005.

Next we get my favorite:

“In recent years China has accounted for nearly half of global growth in oil demand, and every 1 percent of G.D.P. growth in China added 10 to 30 percent to the price of oil.”

I’m still trying to figure this one out. China consumes a bit more than half as much oil as the U.S., but somehow if its GDP increases by 1 percent, the price of oil rises by 10-30 percent. How exactly does that work? If U.S. GDP rises by 1 percent, does the price of oil rise 20-60 percent.

Finally, we are told that:

“China’s slowdown is also opening the door to a revival in American manufacturing. China is suffering many symptoms typical of a maturing miracle economy, from a strengthening currency to rising wages, land prices and transport costs, while the United States has a weak currency, stagnant wages and a moribund property market. The dollar is near record lows (in inflation-adjusted terms) against many of its trading partners, including China.”

I understand the point about relative prices, but don’t we have a better export market if China is growing rapidly? What did I learn in my econ 101 class that was wrong, don’t fast-growing countries have more rapid import growth than slow-growing countries?

Perhaps there is something that made sense in this piece, but it’s not easy to find. It’s hard to understand how a piece so chock full of errors finds its way into the NYT oped page.

I’m shorting Morgan Stanley after reading the NYT column on China by Ruchir Sharma, the head of emerging market equities at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. The piece begins by telling readers:

“more than half of Americans think China is already the world’s leading economy — an astonishing misperception, given that China’s gross domestic product is still less than half of America’s.”

That is not what our friends at the IMF say. On a purchasing power parity basis, which assigns the same set of prices to goods and services produced in both countries, China is already almost 80 percent of the size of the U.S. economy. There is also some serious research suggesting that because of mis-measurement of prices in rural areas, China’s economy is already larger than the U.S. economy.

The piece then goes on to tell us:

“It is well known that developing nations hit a “middle-income trap,” and stop catching up to rich nations, when per-capita income reaches about $5,000 to $15,000 (in current dollars). The examples (Brazil, Mexico, Malaysia) are numerous.”

Huh? This is well-known to whom? This is a huge range (imagine per capita GDP in the U.S. tripled to $150,000 per person) that includes almost 70 countries. It makes a huge difference whether a country’s growth slows near the bottom of this range, where they are still relatively poor, as opposed to the top, where they are decidedly middle class.

Furthermore, countries enter this range with radically different growth paths. The speedy growers like China are the exception. More typically countries edge up into this range with modest growth rates. In the more typical case, there is not much room for a slowdown. Of course in some of the fast growers, like Malaysia, one of Sharma’s examples of a slowdown country, there is little evidence of a slowdown as they maintain rapid growth right through this range.

Then Sharma tells us that China passed his $5,000 mark last year. Actually the IMF says it was 2007, and if the understatement view is right, China hit this mark as early as 2005.

Next we get my favorite:

“In recent years China has accounted for nearly half of global growth in oil demand, and every 1 percent of G.D.P. growth in China added 10 to 30 percent to the price of oil.”

I’m still trying to figure this one out. China consumes a bit more than half as much oil as the U.S., but somehow if its GDP increases by 1 percent, the price of oil rises by 10-30 percent. How exactly does that work? If U.S. GDP rises by 1 percent, does the price of oil rise 20-60 percent.

Finally, we are told that:

“China’s slowdown is also opening the door to a revival in American manufacturing. China is suffering many symptoms typical of a maturing miracle economy, from a strengthening currency to rising wages, land prices and transport costs, while the United States has a weak currency, stagnant wages and a moribund property market. The dollar is near record lows (in inflation-adjusted terms) against many of its trading partners, including China.”

I understand the point about relative prices, but don’t we have a better export market if China is growing rapidly? What did I learn in my econ 101 class that was wrong, don’t fast-growing countries have more rapid import growth than slow-growing countries?

Perhaps there is something that made sense in this piece, but it’s not easy to find. It’s hard to understand how a piece so chock full of errors finds its way into the NYT oped page.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay, I know that picking on George Will might seem like cheap fun, but as an oped columnist for the Washington Post we are supposed to take him seriously. Today Will is beating up on states that don’t follow his pro-rich prescriptions focusing on California and my home state of Illinois.

Let me start with my favorite Will line:

“From September through December 2008, the premium that investors demanded before they would buy California debt rather than U.S. Treasurys jumped from 24 to 271 basis points (100 points equals 1 percent). The bond market, the only remaining reality check for state politicians, must be allowed to work.”

Okay, boys and girls, can anyone think of anything that might have affected spreads in the bond market in the fall of 2008? (Hint: Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke and then Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson were running around screaming that the world was about to end.)

That’s right, we had the collapse of Lehman Brothers and a financial freeze-up. The yield on anything that wasn’t U.S. Treasury bonds soared in this period. In other words, Will’s statement here means absolutely nothing — but it is good enough for the Washington Post editorial page.

As far as the Illinois bashing, Will tells us that:

“The Illinois Policy Institute, a limited-government think tank, in a report cheekily titled “Another $54 Billion!?” argues that in addition to the $83 billion in pension underfunding the state acknowledges, there is $54 billion in unfunded retiree health liabilities over the next 30 years.”

Hmmm, $83 billion in unfunded liabilities? That sounds scaaaary. If the oped page imposed any standards on its writers it might have asked Will to express this number as a share of state income over this period, since no one (I mean no one) has any clue how large an expenditure $83 billion is for Illinois over the next 30 years. The answer is that it would be equal to around 0.7 percent of the state’s projected income over this period. That is not trivial, but not exactly the sort of expenditure that implies the immiseration of the population.

Projections of health care costs are highly uncertain. The one thing that we can say is that if protectionists like Will didn’t have such control over policy, we could save an incredible amount of money by purchasing more of our health care from the more efficient systems in other countries. The private health care system is a cesspool of waste and corruption. This raises costs for everyone, including public sector employers.

Will also tells us that it is unrealistic for Illinois to expect any segment of its pension fund investments to produce 8.5 percent yields. Obviously arithmetic was never Will’s strong suit.

Finally Will tells us:

“Illinois’ unemployment rate increased faster than any other state’s in 2011.”

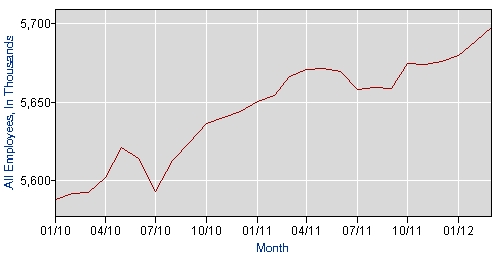

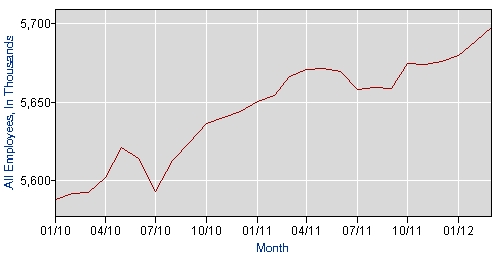

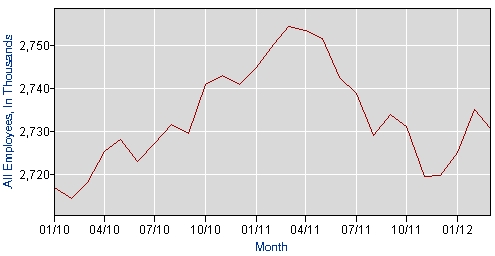

That’s interesting. Let’s compare employment growth in Illinois in 2011 to employment growth in neighboring Wisconsin, which is run by a right-wing favorite: public sector union busting Scott Walker. Since January of 2011 Illinois has created 47,400 jobs, an increase in employment of a bit more than 0.8 percent. That’s not great, but not awful either.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

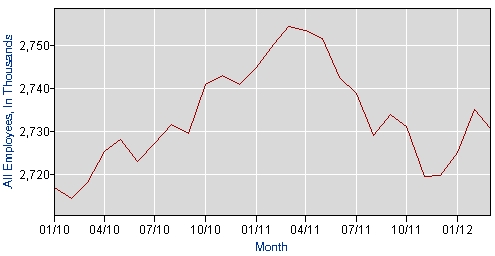

By contrast, Wisconsin lost 14,200 jobs over this period, or neary 0.5 percent of total employment.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

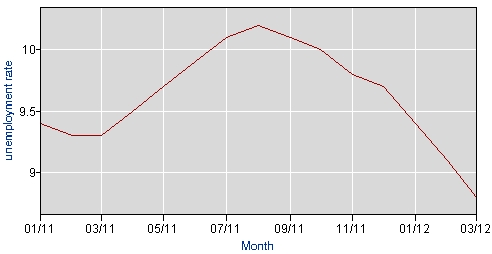

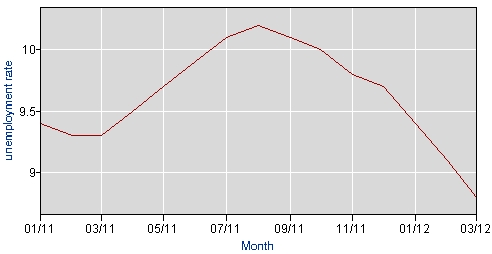

If the unemployment rate rose more in this period in Illinois than in Wisconsin than presumably it is because people in Illinois were out looking for work because the state was creating new jobs. By contrast, in Wisconsin workers probably gave up looking, knowing that there were no jobs available.

But the really fun part of the story is that Will had to be careful to specify that he was only talking about the unemployment rate in 2011. The reason is that Illinois’ unemployment rate has fallen by 0.9 percentage points since December of 2011 and is now 0.6 percentage points below its January 2011 level. Including this fact would be the honest thing to do, but hey, this is George Will and the Washington Post oped page.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Okay, I know that picking on George Will might seem like cheap fun, but as an oped columnist for the Washington Post we are supposed to take him seriously. Today Will is beating up on states that don’t follow his pro-rich prescriptions focusing on California and my home state of Illinois.

Let me start with my favorite Will line:

“From September through December 2008, the premium that investors demanded before they would buy California debt rather than U.S. Treasurys jumped from 24 to 271 basis points (100 points equals 1 percent). The bond market, the only remaining reality check for state politicians, must be allowed to work.”

Okay, boys and girls, can anyone think of anything that might have affected spreads in the bond market in the fall of 2008? (Hint: Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke and then Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson were running around screaming that the world was about to end.)

That’s right, we had the collapse of Lehman Brothers and a financial freeze-up. The yield on anything that wasn’t U.S. Treasury bonds soared in this period. In other words, Will’s statement here means absolutely nothing — but it is good enough for the Washington Post editorial page.

As far as the Illinois bashing, Will tells us that:

“The Illinois Policy Institute, a limited-government think tank, in a report cheekily titled “Another $54 Billion!?” argues that in addition to the $83 billion in pension underfunding the state acknowledges, there is $54 billion in unfunded retiree health liabilities over the next 30 years.”

Hmmm, $83 billion in unfunded liabilities? That sounds scaaaary. If the oped page imposed any standards on its writers it might have asked Will to express this number as a share of state income over this period, since no one (I mean no one) has any clue how large an expenditure $83 billion is for Illinois over the next 30 years. The answer is that it would be equal to around 0.7 percent of the state’s projected income over this period. That is not trivial, but not exactly the sort of expenditure that implies the immiseration of the population.

Projections of health care costs are highly uncertain. The one thing that we can say is that if protectionists like Will didn’t have such control over policy, we could save an incredible amount of money by purchasing more of our health care from the more efficient systems in other countries. The private health care system is a cesspool of waste and corruption. This raises costs for everyone, including public sector employers.

Will also tells us that it is unrealistic for Illinois to expect any segment of its pension fund investments to produce 8.5 percent yields. Obviously arithmetic was never Will’s strong suit.

Finally Will tells us:

“Illinois’ unemployment rate increased faster than any other state’s in 2011.”

That’s interesting. Let’s compare employment growth in Illinois in 2011 to employment growth in neighboring Wisconsin, which is run by a right-wing favorite: public sector union busting Scott Walker. Since January of 2011 Illinois has created 47,400 jobs, an increase in employment of a bit more than 0.8 percent. That’s not great, but not awful either.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

By contrast, Wisconsin lost 14,200 jobs over this period, or neary 0.5 percent of total employment.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If the unemployment rate rose more in this period in Illinois than in Wisconsin than presumably it is because people in Illinois were out looking for work because the state was creating new jobs. By contrast, in Wisconsin workers probably gave up looking, knowing that there were no jobs available.

But the really fun part of the story is that Will had to be careful to specify that he was only talking about the unemployment rate in 2011. The reason is that Illinois’ unemployment rate has fallen by 0.9 percentage points since December of 2011 and is now 0.6 percentage points below its January 2011 level. Including this fact would be the honest thing to do, but hey, this is George Will and the Washington Post oped page.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In reporting on the victory of in the first round of the French presidential elections the NYT noted Mr. Hollande’s opposition to further austerity measures. It then told readers:

“But while Mr. Sarkozy puts his emphasis more on spending cuts, reducing the tax burden on companies and liberalizing the labor market, Mr. Hollande has charted a traditional socialist path of public spending and job creation. That, some economists say, is likely to make matters worse, possibly sending financial markets into a tailspin that invites further chaos.

‘The real problem is the preference for public spending,’ said Nicolas Baverez, an economist and author. ‘The main candidates continue to believe that it is the state that creates jobs and that will innovate, and this is wrong. Public spending is 56.6 percent of gross domestic product, which is huge. And the increase in public spending and taxes is downsizing the private sector and private jobs.'”

While “some economists” do say things like this, other economists, including folks like Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, say that austerity as a way to control budget deficits is self defeating in the current economic situation. It reduces GDP, which in turn lowers tax collections and raises expenditures on items like unemployment benefits.

Rather than just telling readers what “some” economists say on the virtues of austerity, it would have been helpful to include the views of what some other economists say.

(Thanks to Josh Greenstein for calling this one to my attention.)

In reporting on the victory of in the first round of the French presidential elections the NYT noted Mr. Hollande’s opposition to further austerity measures. It then told readers:

“But while Mr. Sarkozy puts his emphasis more on spending cuts, reducing the tax burden on companies and liberalizing the labor market, Mr. Hollande has charted a traditional socialist path of public spending and job creation. That, some economists say, is likely to make matters worse, possibly sending financial markets into a tailspin that invites further chaos.

‘The real problem is the preference for public spending,’ said Nicolas Baverez, an economist and author. ‘The main candidates continue to believe that it is the state that creates jobs and that will innovate, and this is wrong. Public spending is 56.6 percent of gross domestic product, which is huge. And the increase in public spending and taxes is downsizing the private sector and private jobs.'”

While “some economists” do say things like this, other economists, including folks like Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, say that austerity as a way to control budget deficits is self defeating in the current economic situation. It reduces GDP, which in turn lowers tax collections and raises expenditures on items like unemployment benefits.

Rather than just telling readers what “some” economists say on the virtues of austerity, it would have been helpful to include the views of what some other economists say.

(Thanks to Josh Greenstein for calling this one to my attention.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

With the release of the latest Social Security trustees report the scare stories have been coming fast and furious. In this vein, Marketplace radio had an interview with Olivia Mitchell, the head of the Pension Research Council. In this interview, Mitchell commented on the bonds held by the Social Security trust fund:

“If you take a narrow view, what you understand is that there’s a trust fund, which is supposed to be the piggy bank whereby if the funds run short, the Social Security Administration can go and claim these bonds. But if you take the broad view — which I do take — you have to understand that the money actually has been spent. And so what it means is we’ll either have to raise taxes, or cut expenditures, or issue more debt to be able to pay the scheduled benefits.”

Of course Professor Mitchell’s “broad view” would apply to any bonds issued by the federal government. For example, if Peter Peterson were to decide to cash in $1 billion in U.S. government bonds on their due date, the government would have to “raise taxes, or cut expenditures, or issue more debt” to be able to pay off Mr. Peterson’s bonds.

Ordinarily we would not say that this fact means that Peter Peterson does not actually have the $1 billion in wealth implied by his bonds. In fact, the government’s financial situation would probably never enter a discussion of Peter Peterson’s wealth. In the same vein, since Social Security has a separate account under the law, it is hard to see what relevance Professor Mitchell’s broad view has to the system’s finances.

With the release of the latest Social Security trustees report the scare stories have been coming fast and furious. In this vein, Marketplace radio had an interview with Olivia Mitchell, the head of the Pension Research Council. In this interview, Mitchell commented on the bonds held by the Social Security trust fund:

“If you take a narrow view, what you understand is that there’s a trust fund, which is supposed to be the piggy bank whereby if the funds run short, the Social Security Administration can go and claim these bonds. But if you take the broad view — which I do take — you have to understand that the money actually has been spent. And so what it means is we’ll either have to raise taxes, or cut expenditures, or issue more debt to be able to pay the scheduled benefits.”

Of course Professor Mitchell’s “broad view” would apply to any bonds issued by the federal government. For example, if Peter Peterson were to decide to cash in $1 billion in U.S. government bonds on their due date, the government would have to “raise taxes, or cut expenditures, or issue more debt” to be able to pay off Mr. Peterson’s bonds.

Ordinarily we would not say that this fact means that Peter Peterson does not actually have the $1 billion in wealth implied by his bonds. In fact, the government’s financial situation would probably never enter a discussion of Peter Peterson’s wealth. In the same vein, since Social Security has a separate account under the law, it is hard to see what relevance Professor Mitchell’s broad view has to the system’s finances.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It seems like just yesterday when Mexico was being held up as a paragon of free enterprise, in contrast to Argentina, which was nationalizing its oil company. (Okay, it was two days ago.) Anyhow, it seems that Mexico’s government is preparing to impose new restrictions on its state-owned oil company.

It seems like just yesterday when Mexico was being held up as a paragon of free enterprise, in contrast to Argentina, which was nationalizing its oil company. (Okay, it was two days ago.) Anyhow, it seems that Mexico’s government is preparing to impose new restrictions on its state-owned oil company.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an article on the release of the 2012 Social Security trustees report the Washington Post told readers that:

“Social Security’s bleak outlook is primarily driven by the ever-larger numbers of people in the baby boom generation entering retirement.”

Actually the fact that baby boomers would enter retirement is not news. Back in 1983, the Greenspan Commission knew that the baby boomers would retire, yet they still projected that the program would be able to pay all promised benefits into the 2050s.

The main reason that the program’s finances have deteriorated relative to the projected path is that wage growth has not kept pace with the path projected. This is in part due to the fact that productivity growth slowed in the 80s, before accelerating again in the mid-90s and in part due to the fact that much more wage income now goes to people earning above the taxable cap.

In 1983 only 10 percent of wage income fell above the cap and escaped taxation. Now more than 18 percent of wage income is above the cap.

In an article on the release of the 2012 Social Security trustees report the Washington Post told readers that:

“Social Security’s bleak outlook is primarily driven by the ever-larger numbers of people in the baby boom generation entering retirement.”

Actually the fact that baby boomers would enter retirement is not news. Back in 1983, the Greenspan Commission knew that the baby boomers would retire, yet they still projected that the program would be able to pay all promised benefits into the 2050s.

The main reason that the program’s finances have deteriorated relative to the projected path is that wage growth has not kept pace with the path projected. This is in part due to the fact that productivity growth slowed in the 80s, before accelerating again in the mid-90s and in part due to the fact that much more wage income now goes to people earning above the taxable cap.

In 1983 only 10 percent of wage income fell above the cap and escaped taxation. Now more than 18 percent of wage income is above the cap.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s always a good idea to look at the data that you present to readers when you write about it. It appears that CNNMoney forgot to do this in an article whose first sentence warned of the, “the burgeoning costs of Medicare and Social Security.”

The chart shows a modest uptick in the cost of Social Security, measured as a share of GDP, over the next two decades, then a line that is essentially flat over the remaining 55 years of the projection period. Medicare does have costs that could be called “burgeoning,” but that is the story of our broken private health care system.

It’s always a good idea to look at the data that you present to readers when you write about it. It appears that CNNMoney forgot to do this in an article whose first sentence warned of the, “the burgeoning costs of Medicare and Social Security.”

The chart shows a modest uptick in the cost of Social Security, measured as a share of GDP, over the next two decades, then a line that is essentially flat over the remaining 55 years of the projection period. Medicare does have costs that could be called “burgeoning,” but that is the story of our broken private health care system.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article on the financial difficulties of the Postal Service concluded with a comment from Art Sackler, the chairman of the Coalition for a 21st Century Postal Service:

“They haven’t had a good track record when it comes to developing new lines of business.”

This organization is identified as “a mailing industry group that includes companies like FedEx.”

It might have been worth reminding readers that FedEx and UPS have in the past used their political power to limit the ability of the Postal Service to compete with them. A few years back the Postal Service had a successful ad campaign that highlighted the fact that its express service was much cheaper than FedEx or UPS.

These companies then went to court to try to stop the campaign. After they lost their court case, they then went to Congress, which helped to persuade the Postal Service to end this particular ad campaign. At least in this particular case the Postal Service’s main problem was a lack of political clout, not a bad business model.

A NYT article on the financial difficulties of the Postal Service concluded with a comment from Art Sackler, the chairman of the Coalition for a 21st Century Postal Service:

“They haven’t had a good track record when it comes to developing new lines of business.”

This organization is identified as “a mailing industry group that includes companies like FedEx.”

It might have been worth reminding readers that FedEx and UPS have in the past used their political power to limit the ability of the Postal Service to compete with them. A few years back the Postal Service had a successful ad campaign that highlighted the fact that its express service was much cheaper than FedEx or UPS.

These companies then went to court to try to stop the campaign. After they lost their court case, they then went to Congress, which helped to persuade the Postal Service to end this particular ad campaign. At least in this particular case the Postal Service’s main problem was a lack of political clout, not a bad business model.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión