Many pundits have been telling us that the reason that workers are not getting jobs is that employers cannot find workers with the skills needed for the positions available. I have regularly ridiculed this position, since if it were true we would see sharply rising wages in some sectors as employers competed for the limited group of workers who have the necessary skills. Of course we don’t see any major sector of the labor market with rapidly rising wages.

However, I must now reconsider this view. David Brooks presented compelling evidence that employers cannot find workers with the necessary skills in his column today. In this column he criticizes Obama for attacking the budget proposed by Paul Ryan (and endorsed by the House Republicans and Governor Romney), which, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), would eliminate the federal government except for health care programs, Social Security, and defense by 2050.

Brooks focuses on the more near-term story. He tells readers:

“In 2013, according to Veronique de Rugy of George Mason University, the Ryan budget would be about 5 percent smaller than the Obama budget, and it would grow a percent or two more slowly each year. After 10 years, government would be smaller under Ryan, but, as Daniel Mitchell of the Cato Institute complains, it would still take up a larger share of national output than when Bill Clinton left office.”

Yeah in 2023 the budget will be larger than the last Clinton budget, what could Obama possibly be complaining about?

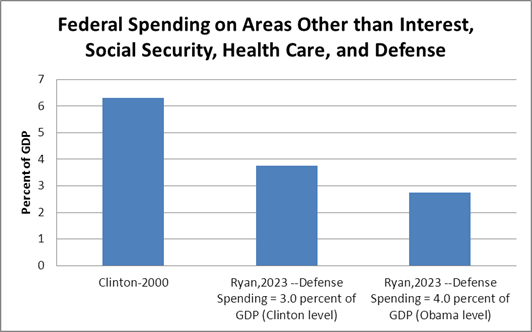

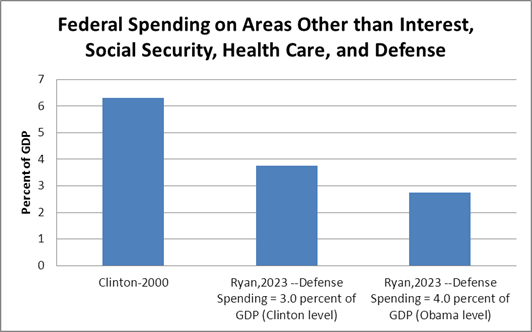

Okay, now if David Brooks knew arithmetic, he would be able to look at the CBO projections and see that in 2023, it projects that spending on items other than interest, health care spending, and Social Security is projected to be equal to 6.75 percent of GDP in 2023. He would also look back and see that this spending was equal to roughly 9.3 percent of spending in 2000.

Currently, military spending (excluding the war in Afghanistan) is approximately 4.0 percent of GDP. If Representative Ryan left military spending at this level, as he has suggested in his criticisms of President Obama’s proposed cuts, his 2023 budget would leave an amount equal to 2.75 percent of GDP for everything else. If he allowed the defense budget to fall back to 3.0 percent of GDP, its 2000 level and also the low point for the last 60 years, he would leave 3.75 percent of GDP for everything else.

Since President Clinton’s 2000 budget allotted 6.3 percent of GDP for this everything else category (e.g. roads and bridges, education, medical research, the Justice Department and the federal prison system, and the national park system) the Ryan-Romney budget implies a cut of between 40 and 56 percent in most categories of government spending. If David Brooks knew arithmetic, he would realize that cuts of this magnitude are a big deal and that Obama is absolutely right to make a big issue of them.

Source: Congressional Budget Office and author’s calculations, see text.

Unfortunately, the NYT is unable to find columnists who know arithmetic. Therefore, they have to print David Brooks making silly assertions about the Ryan budget and President Obama’s criticisms of it.

Many pundits have been telling us that the reason that workers are not getting jobs is that employers cannot find workers with the skills needed for the positions available. I have regularly ridiculed this position, since if it were true we would see sharply rising wages in some sectors as employers competed for the limited group of workers who have the necessary skills. Of course we don’t see any major sector of the labor market with rapidly rising wages.

However, I must now reconsider this view. David Brooks presented compelling evidence that employers cannot find workers with the necessary skills in his column today. In this column he criticizes Obama for attacking the budget proposed by Paul Ryan (and endorsed by the House Republicans and Governor Romney), which, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), would eliminate the federal government except for health care programs, Social Security, and defense by 2050.

Brooks focuses on the more near-term story. He tells readers:

“In 2013, according to Veronique de Rugy of George Mason University, the Ryan budget would be about 5 percent smaller than the Obama budget, and it would grow a percent or two more slowly each year. After 10 years, government would be smaller under Ryan, but, as Daniel Mitchell of the Cato Institute complains, it would still take up a larger share of national output than when Bill Clinton left office.”

Yeah in 2023 the budget will be larger than the last Clinton budget, what could Obama possibly be complaining about?

Okay, now if David Brooks knew arithmetic, he would be able to look at the CBO projections and see that in 2023, it projects that spending on items other than interest, health care spending, and Social Security is projected to be equal to 6.75 percent of GDP in 2023. He would also look back and see that this spending was equal to roughly 9.3 percent of spending in 2000.

Currently, military spending (excluding the war in Afghanistan) is approximately 4.0 percent of GDP. If Representative Ryan left military spending at this level, as he has suggested in his criticisms of President Obama’s proposed cuts, his 2023 budget would leave an amount equal to 2.75 percent of GDP for everything else. If he allowed the defense budget to fall back to 3.0 percent of GDP, its 2000 level and also the low point for the last 60 years, he would leave 3.75 percent of GDP for everything else.

Since President Clinton’s 2000 budget allotted 6.3 percent of GDP for this everything else category (e.g. roads and bridges, education, medical research, the Justice Department and the federal prison system, and the national park system) the Ryan-Romney budget implies a cut of between 40 and 56 percent in most categories of government spending. If David Brooks knew arithmetic, he would realize that cuts of this magnitude are a big deal and that Obama is absolutely right to make a big issue of them.

Source: Congressional Budget Office and author’s calculations, see text.

Unfortunately, the NYT is unable to find columnists who know arithmetic. Therefore, they have to print David Brooks making silly assertions about the Ryan budget and President Obama’s criticisms of it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would have been worth mentioning in a piece that reported that profit growth is expected to slow in the first quarter of 2012 and may stagnate for the year as a whole. With profits already near post-war highs as a share of income, they can’t grow any more rapidly than GDP unless the profit share goes still higher. Since it is unreasonable to expect the share of GDP going to profits to continue to rise indefinitely, a slowdown in profit growth was virtually inevitable.

That would have been worth mentioning in a piece that reported that profit growth is expected to slow in the first quarter of 2012 and may stagnate for the year as a whole. With profits already near post-war highs as a share of income, they can’t grow any more rapidly than GDP unless the profit share goes still higher. Since it is unreasonable to expect the share of GDP going to profits to continue to rise indefinitely, a slowdown in profit growth was virtually inevitable.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

At least it thinks that this is a reasonable position deserving some of the paper’s scarce column space. The Post printed a column today by Michael W. Hodin warning about the “inexorable” aging of the population. At one point Hodin asks:

“What if we reimagined and redefined what it means to age? What if, in light of our longer lifespans, ‘middle age’ were 55 to 75?”

While the piece implies that aging poses some radically new problem for the world, the fact is that populations have been aging for well over a hundred years due to both increases in life expectancy and also declining birth rates. In other words, this is just a continuation of a long trend, not a departure from it.

Furthermore, just as aging of the population in the past has been associated with a rise in the standard of living there is no reason to believe that this will not be the case in the future. If economies can sustain a 2.0 percent rate of productivity growth (slightly less than the average in the U.S. over the last 60 years) then output per worker hour will be almost 120 percent higher in 2050 than it is today.

This increase in productivity would swamp the effect of even the most rapid growth of a population of aged dependent. For example, if we have 3 workers for every retiree today and expect to have 2 workers for every retiree in 2050 (roughly the projected numbers), if retirees have a standard of living that is 75 percent as high as workers then workers and retirees would be still be able to enjoy standards of living that are close to twice their current level in this story. This does not even count the savings from the lower share of young dependents that would be the result of lower birth rates.

The piece also mistakenly implies that fiscal crises facing several European countries and state governments in the United States are due to the aging of the population. Actually, we had a huge economic crisis as a result of the collapse of housing bubbles in the United States and Europe. The resulting downturn is the cause of these fiscal crises. Mr. Hodin was apparently unaware of the economic crisis.

At least it thinks that this is a reasonable position deserving some of the paper’s scarce column space. The Post printed a column today by Michael W. Hodin warning about the “inexorable” aging of the population. At one point Hodin asks:

“What if we reimagined and redefined what it means to age? What if, in light of our longer lifespans, ‘middle age’ were 55 to 75?”

While the piece implies that aging poses some radically new problem for the world, the fact is that populations have been aging for well over a hundred years due to both increases in life expectancy and also declining birth rates. In other words, this is just a continuation of a long trend, not a departure from it.

Furthermore, just as aging of the population in the past has been associated with a rise in the standard of living there is no reason to believe that this will not be the case in the future. If economies can sustain a 2.0 percent rate of productivity growth (slightly less than the average in the U.S. over the last 60 years) then output per worker hour will be almost 120 percent higher in 2050 than it is today.

This increase in productivity would swamp the effect of even the most rapid growth of a population of aged dependent. For example, if we have 3 workers for every retiree today and expect to have 2 workers for every retiree in 2050 (roughly the projected numbers), if retirees have a standard of living that is 75 percent as high as workers then workers and retirees would be still be able to enjoy standards of living that are close to twice their current level in this story. This does not even count the savings from the lower share of young dependents that would be the result of lower birth rates.

The piece also mistakenly implies that fiscal crises facing several European countries and state governments in the United States are due to the aging of the population. Actually, we had a huge economic crisis as a result of the collapse of housing bubbles in the United States and Europe. The resulting downturn is the cause of these fiscal crises. Mr. Hodin was apparently unaware of the economic crisis.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is well-known that the Washington Post is obsessed with the budget deficit and that it feels little need to restrict this obsession to the opinion pages (hence its nickname, “Fox on 15th Street”). It once again ran an editorial in its news section as it told readers about the country’s “rocketing debt.”

The editorial then asked:

“Why can’t America’s leaders, at the helm of such a wealthy country, find a solution that both puts the nation on a long-term path to financial security and preserves the vast array of vital services government provides?”

Of course the obvious answer is that there is no obvious reason that the country should be worried right now about writing down numbers on paper that show the nation will be on a “long-term path to financial security and preserves the vast array of vital services government provides.”

The immediate problem facing the country are the tens of millions of workers who are unemployed or underemployed due to economic mismanagement by people like Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke. The question that all reasonable people should be asking is why America’s leaders can’t find a solution that will put these people back to work? After all, Keynes showed us how to restore an economy to full employment more than 70 years ago. The only reason that the country currently faces a large budget deficit and rising debt to GDP ratio is the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble.

It is also worth reminding readers that the horror stories of exploding health care costs are entirely the result of the broken health care system in the United States. We spend more than twice as much per person on health care in the United States than in other wealthy countries. If we had the same per person health care costs as in other countries then we would be looking at enormous budget surpluses, not deficits. That is why serious people focus on the problem of health care costs, not budget deficits.

The piece also includes the assertion that:

“Economists say high debt levels can increase the risk of financial crises.”

To make this more accurate the statement should say that:

“Economists who failed to see the last economic crisis say high debt levels can increase the risk of financial crises.”

It is well-known that the Washington Post is obsessed with the budget deficit and that it feels little need to restrict this obsession to the opinion pages (hence its nickname, “Fox on 15th Street”). It once again ran an editorial in its news section as it told readers about the country’s “rocketing debt.”

The editorial then asked:

“Why can’t America’s leaders, at the helm of such a wealthy country, find a solution that both puts the nation on a long-term path to financial security and preserves the vast array of vital services government provides?”

Of course the obvious answer is that there is no obvious reason that the country should be worried right now about writing down numbers on paper that show the nation will be on a “long-term path to financial security and preserves the vast array of vital services government provides.”

The immediate problem facing the country are the tens of millions of workers who are unemployed or underemployed due to economic mismanagement by people like Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke. The question that all reasonable people should be asking is why America’s leaders can’t find a solution that will put these people back to work? After all, Keynes showed us how to restore an economy to full employment more than 70 years ago. The only reason that the country currently faces a large budget deficit and rising debt to GDP ratio is the economic downturn caused by the collapse of the housing bubble.

It is also worth reminding readers that the horror stories of exploding health care costs are entirely the result of the broken health care system in the United States. We spend more than twice as much per person on health care in the United States than in other wealthy countries. If we had the same per person health care costs as in other countries then we would be looking at enormous budget surpluses, not deficits. That is why serious people focus on the problem of health care costs, not budget deficits.

The piece also includes the assertion that:

“Economists say high debt levels can increase the risk of financial crises.”

To make this more accurate the statement should say that:

“Economists who failed to see the last economic crisis say high debt levels can increase the risk of financial crises.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT did some really serious he said/she said budget reporting in a front page article on the House Republican budget proposed by Representative Paul Ryan, which also has been endorsed by Governor Romney. The article reports what both Democrats and Republicans say about the Ryan budget without making any effort to verify the extent to which the statements are true. In several cases, this could be quite easily done.

For example, the article tells readers in reference to the Ryan budget and the budget proposed by Mitt Romney:

“Both budgets, the Obama campaign asserts, would cut taxes sharply for the wealthy; gut public education, medical research, and other government programs; and increase the burden on the elderly to pay for their own health care.”

This is not just something that “the Obama campaign asserts,” it happens to be true. Both plans call for sharp reductions in the tax rates paid by high income earners. Both have explicitly ruled out eliminating the tax breaks that most directly affect high income taxpayers: the special lower tax rate on capital gains and dividend income.

In terms of the cuts to public education, medical research and other government programs, it is possible to go to the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the Ryan budget, which was done under his direction. This analysis shows that all discretionary spending (the category which includes these items), plus non-health mandatory spending, is projected to shrink to 3.75 percent of GDP by 2050.

This 3.75 percent of GDP includes defense spending. Currently defense spending is close to 4.0 percent of GDP, not including the cost of the war in Afghanistan. It has never been below 3.0 percent of GDP since the start of the Cold War. In other words, it is an objective fact that the Ryan plan would:

“gut public education, medical research, and other government programs; and increase the burden on the elderly to pay for their own health care,”

not just something that the Obama campaign asserts. The NYT should have pointed this out to readers. The NYT’s reporters have the time to examine CBO’s analysis of the Ryan budget, most readers do not.

At one point the article also wrongly refers to “parts of the [budget] plan intended to spur economic growth.” It is not clear that any parts of the budget plan are “intended” to spur growth. There are parts of the plan, such as the tax cuts for the wealthy, which Romney and Ryan claim are intended to spur growth, but the NYT has no idea whether this is really the intent of these cuts.

It is entirely possible that the reason that Romney and Ryan propose cuts in tax rates for the wealthy is to give more money to wealthy people, many of whom are supporting their political efforts. Since there is no evidence that these tax cuts will actually lead to more growth, it is at least as plausible that the intention is to give money to the wealthy (something we know that tax cuts will do), as it is that they are intended to promote growth.

The NYT did some really serious he said/she said budget reporting in a front page article on the House Republican budget proposed by Representative Paul Ryan, which also has been endorsed by Governor Romney. The article reports what both Democrats and Republicans say about the Ryan budget without making any effort to verify the extent to which the statements are true. In several cases, this could be quite easily done.

For example, the article tells readers in reference to the Ryan budget and the budget proposed by Mitt Romney:

“Both budgets, the Obama campaign asserts, would cut taxes sharply for the wealthy; gut public education, medical research, and other government programs; and increase the burden on the elderly to pay for their own health care.”

This is not just something that “the Obama campaign asserts,” it happens to be true. Both plans call for sharp reductions in the tax rates paid by high income earners. Both have explicitly ruled out eliminating the tax breaks that most directly affect high income taxpayers: the special lower tax rate on capital gains and dividend income.

In terms of the cuts to public education, medical research and other government programs, it is possible to go to the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the Ryan budget, which was done under his direction. This analysis shows that all discretionary spending (the category which includes these items), plus non-health mandatory spending, is projected to shrink to 3.75 percent of GDP by 2050.

This 3.75 percent of GDP includes defense spending. Currently defense spending is close to 4.0 percent of GDP, not including the cost of the war in Afghanistan. It has never been below 3.0 percent of GDP since the start of the Cold War. In other words, it is an objective fact that the Ryan plan would:

“gut public education, medical research, and other government programs; and increase the burden on the elderly to pay for their own health care,”

not just something that the Obama campaign asserts. The NYT should have pointed this out to readers. The NYT’s reporters have the time to examine CBO’s analysis of the Ryan budget, most readers do not.

At one point the article also wrongly refers to “parts of the [budget] plan intended to spur economic growth.” It is not clear that any parts of the budget plan are “intended” to spur growth. There are parts of the plan, such as the tax cuts for the wealthy, which Romney and Ryan claim are intended to spur growth, but the NYT has no idea whether this is really the intent of these cuts.

It is entirely possible that the reason that Romney and Ryan propose cuts in tax rates for the wealthy is to give more money to wealthy people, many of whom are supporting their political efforts. Since there is no evidence that these tax cuts will actually lead to more growth, it is at least as plausible that the intention is to give money to the wealthy (something we know that tax cuts will do), as it is that they are intended to promote growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Okay folks, this is getting really stupid at this point. The headline of the AP article in the Washington Post on the latest unemployment claims number tells readers:

“weekly US unemployment claims fall to 357,000, a 4-year low, as job market strengthens.”

Before anyone gets too excited, they should be reminded that claims for two weeks ago had originally been reported as 348,000, and last week’s originally reported number had been only slightly higher at 359,000. The upward revision of the weekly unemployment claims numbers has been so consistent that it is virtually certain that this 357,000 number will be revised higher with next week’s report.

It remains to be seen whether it will still be a 4-year low when the data is revised next week. A bit more caution would have been appropriate in assessing this release.

Okay folks, this is getting really stupid at this point. The headline of the AP article in the Washington Post on the latest unemployment claims number tells readers:

“weekly US unemployment claims fall to 357,000, a 4-year low, as job market strengthens.”

Before anyone gets too excited, they should be reminded that claims for two weeks ago had originally been reported as 348,000, and last week’s originally reported number had been only slightly higher at 359,000. The upward revision of the weekly unemployment claims numbers has been so consistent that it is virtually certain that this 357,000 number will be revised higher with next week’s report.

It remains to be seen whether it will still be a 4-year low when the data is revised next week. A bit more caution would have been appropriate in assessing this release.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT deserves credit for correcting an item in an article on the impact of the mandate in Massachusetts that I commented on last week. The piece had repeated the assertion of a person interviewed for the piece that it would cost him $1,200 a month to get the health insurance for himself and his daughter required by the mandate. The on-line exchange shows that the cheapest policy for these two people would be $685 a month. The correction noted this fact.

The NYT deserves credit for correcting an item in an article on the impact of the mandate in Massachusetts that I commented on last week. The piece had repeated the assertion of a person interviewed for the piece that it would cost him $1,200 a month to get the health insurance for himself and his daughter required by the mandate. The on-line exchange shows that the cheapest policy for these two people would be $685 a month. The correction noted this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT did some serious head said/she said reporting when it concluded an article reporting on President Obama’s criticism of the tax cuts for the rich in the Republican budget:

“In theory, tax writers could focus on tax breaks that primarily help the rich, like the deduction for charitable giving, or end the biggest tax breaks only for upper income earners. But Democrats say such selective changes to the tax code would never recoup such large cuts to income tax rates.”

It is not just Democrats who say that taking back a selective group of tax breaks for the rich will not offset a big cut in tax rates. It happens to be true.

The one tax break that could be offsetting, the lower tax rate for dividends and capital gains, has been declared off-limits by the Republicans. The amount of taxes at issue for the remaining tax breaks would not come close to offsetting a reduction in the top marginal tax rate of more than 15 percentage points for the top 1 percent of the income distribution. The NYT should have made that clear to readers.

The NYT did some serious head said/she said reporting when it concluded an article reporting on President Obama’s criticism of the tax cuts for the rich in the Republican budget:

“In theory, tax writers could focus on tax breaks that primarily help the rich, like the deduction for charitable giving, or end the biggest tax breaks only for upper income earners. But Democrats say such selective changes to the tax code would never recoup such large cuts to income tax rates.”

It is not just Democrats who say that taking back a selective group of tax breaks for the rich will not offset a big cut in tax rates. It happens to be true.

The one tax break that could be offsetting, the lower tax rate for dividends and capital gains, has been declared off-limits by the Republicans. The amount of taxes at issue for the remaining tax breaks would not come close to offsetting a reduction in the top marginal tax rate of more than 15 percentage points for the top 1 percent of the income distribution. The NYT should have made that clear to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión