The NYT reported on a conference of European leaders where Latvia’s approach to economic policy was held up as a major success story. The article told readers:

“The small country of Latvia, with a population of two million, was cited as a good, and rare, example for its relatively quick recovery from a 2009 bailout.”

It would have been useful to note that Latvia’s unemployment rate is still well into the double digits. It also would have been worth pointing out that close to 10 percent of Latvia’s workforce has emigrated to other countries in search of work. It is not likely that this record would be viewed as an attractive model to most other European countries.

The NYT reported on a conference of European leaders where Latvia’s approach to economic policy was held up as a major success story. The article told readers:

“The small country of Latvia, with a population of two million, was cited as a good, and rare, example for its relatively quick recovery from a 2009 bailout.”

It would have been useful to note that Latvia’s unemployment rate is still well into the double digits. It also would have been worth pointing out that close to 10 percent of Latvia’s workforce has emigrated to other countries in search of work. It is not likely that this record would be viewed as an attractive model to most other European countries.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Get out a second Nobel for Paul Krugman. His column today is exactly on the mark in its framing of the right-wing legislative agenda of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). This is not a group that is committed to the free market.

In area after area, private prisons, private charter schools, private roads, ALEC is about allowing their members to feed off the public trough with sweetheart contracts. Calling these people “free market fundamentalists” is doing them a great favor. It implies that they are acting on a commitment to libertarian principles, as opposed to the reality where they are acting out of a commitment to stuffing their pockets.

Of course this was the point of that 2011 classic, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.

Get out a second Nobel for Paul Krugman. His column today is exactly on the mark in its framing of the right-wing legislative agenda of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). This is not a group that is committed to the free market.

In area after area, private prisons, private charter schools, private roads, ALEC is about allowing their members to feed off the public trough with sweetheart contracts. Calling these people “free market fundamentalists” is doing them a great favor. It implies that they are acting on a commitment to libertarian principles, as opposed to the reality where they are acting out of a commitment to stuffing their pockets.

Of course this was the point of that 2011 classic, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Gretchen Morgenson has done a lot of outstanding reporting on the financial industry over the last decade, however today’s defense of Ed DeMarco, the head of the Federal Housing Finance Authority falls wide of the mark. DeMarco has drawn considerable heat as of late because of his refusal to allow Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to do principal reductions to make it easier for underwater homeowners to stay in her home.

Morgenson defends this refusal by saying that DeMarco’s refusal is actually protecting taxpayers from providing yet another bailout to the banks. Her argument is that many of these underwater homeowners have second liens on their homes which are held by banks. If Fannie and Freddie do principal reductions on the first lien, then it greatly increases the likelihood that these second liens will be paid off, thereby enriching the banks at the taxpayers’ expenses. (If a home goes into foreclosure, the first lien has absolute priority. Not a penny goes to the second lien unless the first lien is paid in full. This means that second loans generally have zero value in a foreclosure.)

There are two problems with this story. The first is that a very large percent of F&F underwater mortgages do not have a second lien. Core Logic estimates that 60 percent of underwater mortgages do not have a second lien. The share is almost certainly higher with F&F loans than with mortgages more generally, since F&F did not get into the worst of the subprime loans where homebuyers put zero down. This means that for the vast majority of underwater mortgages held by F&F there is no issue of subsidizing banks indirectly through a principle write-down, since there is no second loan.

The second issue is that the holder of the first mortgage can negotiate with the holder of the second mortgage to set terms for a principal write-down. It is possible that banks would be obstinate and refuse to make serious concessions. In this case, DeMarco with have a solid reason for refusing to go ahead with write-downs. However he has never indicated publicly that F&F have tried this sort of negotiation and been rebuffed. If this is the case, then DeMarco has a responsibility to explain the problem to the public and Congress. Most likely he has not said anything because he has never attempted to go this route.

Finally, Morgenson offers up a defense of DeMarco’s conduct by noting that foreclosure rates are much lower on F&F loans than on the loans held by banks or in private issue mortgage backed securities. While this is undoubtedly true, it should be expected given that the loans issued by F&F were much higher quality than the loans that were placed in private issue mortgage backed securities.

Since F&F stayed away from the worst subprime and Alt-A mortgages they naturally would have lower default and foreclosure rates on their loans. This is not evidence that they have been especially effective in their modifications.

It is worth pointing out that the debate over this issue has become hugely overblown. It would not make a big difference to the overall economy or even the housing market if DeMarco were to allow principal reductions. The biggest effect is that perhaps another 200,000-300,000 homeowners may be able to avoid foreclosure in the next few years. This would be a good thing for these people. However the impact on the housing market and the economy would be negligible.

Gretchen Morgenson has done a lot of outstanding reporting on the financial industry over the last decade, however today’s defense of Ed DeMarco, the head of the Federal Housing Finance Authority falls wide of the mark. DeMarco has drawn considerable heat as of late because of his refusal to allow Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to do principal reductions to make it easier for underwater homeowners to stay in her home.

Morgenson defends this refusal by saying that DeMarco’s refusal is actually protecting taxpayers from providing yet another bailout to the banks. Her argument is that many of these underwater homeowners have second liens on their homes which are held by banks. If Fannie and Freddie do principal reductions on the first lien, then it greatly increases the likelihood that these second liens will be paid off, thereby enriching the banks at the taxpayers’ expenses. (If a home goes into foreclosure, the first lien has absolute priority. Not a penny goes to the second lien unless the first lien is paid in full. This means that second loans generally have zero value in a foreclosure.)

There are two problems with this story. The first is that a very large percent of F&F underwater mortgages do not have a second lien. Core Logic estimates that 60 percent of underwater mortgages do not have a second lien. The share is almost certainly higher with F&F loans than with mortgages more generally, since F&F did not get into the worst of the subprime loans where homebuyers put zero down. This means that for the vast majority of underwater mortgages held by F&F there is no issue of subsidizing banks indirectly through a principle write-down, since there is no second loan.

The second issue is that the holder of the first mortgage can negotiate with the holder of the second mortgage to set terms for a principal write-down. It is possible that banks would be obstinate and refuse to make serious concessions. In this case, DeMarco with have a solid reason for refusing to go ahead with write-downs. However he has never indicated publicly that F&F have tried this sort of negotiation and been rebuffed. If this is the case, then DeMarco has a responsibility to explain the problem to the public and Congress. Most likely he has not said anything because he has never attempted to go this route.

Finally, Morgenson offers up a defense of DeMarco’s conduct by noting that foreclosure rates are much lower on F&F loans than on the loans held by banks or in private issue mortgage backed securities. While this is undoubtedly true, it should be expected given that the loans issued by F&F were much higher quality than the loans that were placed in private issue mortgage backed securities.

Since F&F stayed away from the worst subprime and Alt-A mortgages they naturally would have lower default and foreclosure rates on their loans. This is not evidence that they have been especially effective in their modifications.

It is worth pointing out that the debate over this issue has become hugely overblown. It would not make a big difference to the overall economy or even the housing market if DeMarco were to allow principal reductions. The biggest effect is that perhaps another 200,000-300,000 homeowners may be able to avoid foreclosure in the next few years. This would be a good thing for these people. However the impact on the housing market and the economy would be negligible.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal let Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke get away with a bit of Three-card Monte in a lecture he gave to George Washington University about the Fed’s role in the housing bubble. According to the WSJ Bernanke absolved the Fed of blame for the housing bubble because of its low interest rate policy. He noted that other countries, like the UK, had housing bubbles even though they had more restrictive monetary policy.

This international comparison is very neat in the context of another issue that Bernanke raised in this lecture. The WSJ reported that Bernanke also made a pitch for the importance of central bank independence in reference to Paul Volcker’s tenure as Fed chair:

“Volcker’s tough policies successfully drove down inflation, but caused a recession that stirred the ire of construction workers who would mail two-by-four planks of wood with a nail driven in them to the Fed as a symbol of their protest, Bernanke noted. If Volcker had to face re-election, he might not have been able to sustain his policies.”

Actually, inflation rates fell sharply everywhere in the world in the early 80s. Not all central banks pursued as restrictive a monetary policy as the Fed. This suggests that the high unemployment caused by Volcker’s policies were not necessary for bringing down inflation.

In fact, this is a good argument for a central bank that is more democratically accountable. If Volcker felt as much obligation to protect against excessive unemployment — which negatively affects large segments of the non-rich population — as he did to combat inflation, perhaps he would have managed to contain inflation while inflicting less pain.

On the earlier point about the Fed’s responsibility for allowing the housing bubble to grow to such dangerous levels, some of us who complained about the policy at the time were not advocating higher interest rates. We advocated first and foremost that the Fed use its enormous bully pulpit to call attention to the bubble and to the fact that people buying homes at bubble-inflated prices stood to lose their lives savings.

These warnings could have been backed up by research by the Fed’s huge staff of economists which would have showed that there was an unprecedented run up in house prices with no basis in the fundamentals of the housing market. The Fed could have used the public appearances and congressional testimonies of Greenspan and other Fed officials to bring this evidence to the public’s attention. (Instead, Greenspan argued the opposite, claiming that there was no bubble.)

The Fed also has substantial regulatory powers over the financial industry. They could have used this power to crack down on the widespread issuance and securitization of fraudulent mortgages which was evident to anyone paying attention at the time.

The Wall Street Journal let Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke get away with a bit of Three-card Monte in a lecture he gave to George Washington University about the Fed’s role in the housing bubble. According to the WSJ Bernanke absolved the Fed of blame for the housing bubble because of its low interest rate policy. He noted that other countries, like the UK, had housing bubbles even though they had more restrictive monetary policy.

This international comparison is very neat in the context of another issue that Bernanke raised in this lecture. The WSJ reported that Bernanke also made a pitch for the importance of central bank independence in reference to Paul Volcker’s tenure as Fed chair:

“Volcker’s tough policies successfully drove down inflation, but caused a recession that stirred the ire of construction workers who would mail two-by-four planks of wood with a nail driven in them to the Fed as a symbol of their protest, Bernanke noted. If Volcker had to face re-election, he might not have been able to sustain his policies.”

Actually, inflation rates fell sharply everywhere in the world in the early 80s. Not all central banks pursued as restrictive a monetary policy as the Fed. This suggests that the high unemployment caused by Volcker’s policies were not necessary for bringing down inflation.

In fact, this is a good argument for a central bank that is more democratically accountable. If Volcker felt as much obligation to protect against excessive unemployment — which negatively affects large segments of the non-rich population — as he did to combat inflation, perhaps he would have managed to contain inflation while inflicting less pain.

On the earlier point about the Fed’s responsibility for allowing the housing bubble to grow to such dangerous levels, some of us who complained about the policy at the time were not advocating higher interest rates. We advocated first and foremost that the Fed use its enormous bully pulpit to call attention to the bubble and to the fact that people buying homes at bubble-inflated prices stood to lose their lives savings.

These warnings could have been backed up by research by the Fed’s huge staff of economists which would have showed that there was an unprecedented run up in house prices with no basis in the fundamentals of the housing market. The Fed could have used the public appearances and congressional testimonies of Greenspan and other Fed officials to bring this evidence to the public’s attention. (Instead, Greenspan argued the opposite, claiming that there was no bubble.)

The Fed also has substantial regulatory powers over the financial industry. They could have used this power to crack down on the widespread issuance and securitization of fraudulent mortgages which was evident to anyone paying attention at the time.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The main thing that careful observers know from watching housing data over the years is that the monthly data should be largely ignored when assessing the housing market. The point here is that random factors have a large impact on monthly sales and price numbers, so that the noise often overwhelms the actual information about the housing market in a single month’s release.

To see the point, let’s start with existing home sales. The Realtors reported a small drop in February from an upwardly revised January number. This touched off a round of news stories about the weak state of the housing market. (The February sales number was higher than the unrevised number, meaning that it was higher than the level of sales that we had thought actually took place in January prior to the release.)

Source: National Association of Realtors.

Note that months where we see big changes in one direction are often followed and/or preceded by a big change in the opposite direction. For example, we could have been alarmed by the 3 percent falloff in sales last July, but then we would have been ecstatic over the 9 percent jump in August, only to be put in the doldrums by the 3 percent drop in September.

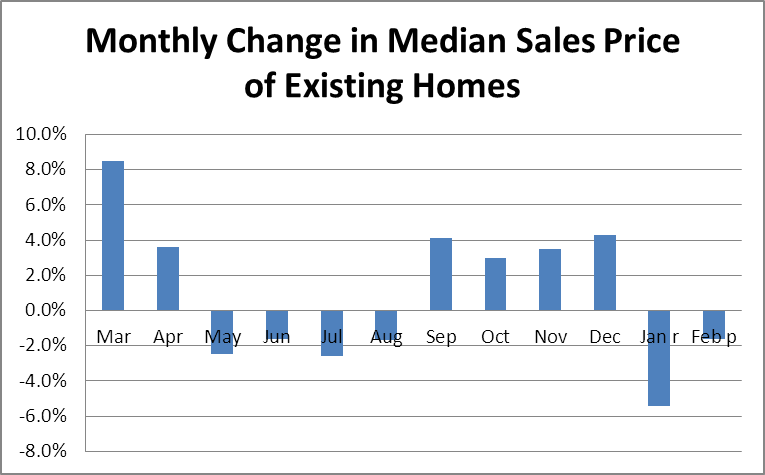

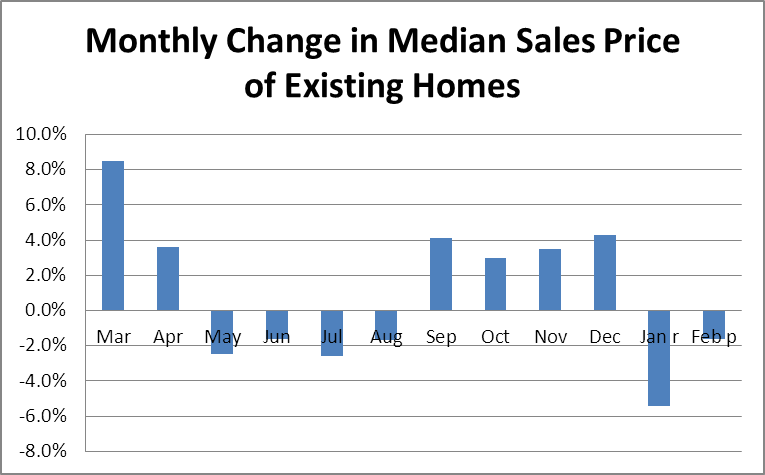

There is a similar story with month to month price changes.

Source: National Association of Realtors.

These data are even more erratic. The 8 percent one-month rise in prices in March must have seemed really exciting. On the other hand, the nearly 5 percent one-month drop back in January must have terrified people. Of course neither of these movements was likely real. These are just random fluctuations in the data.

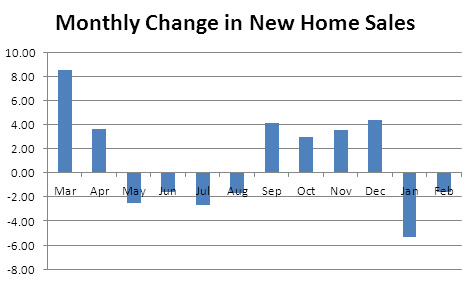

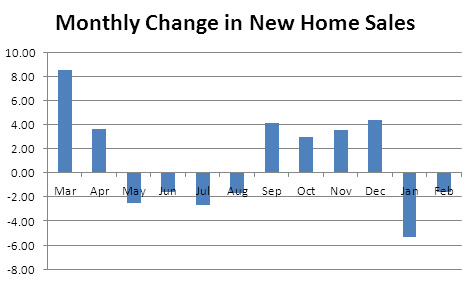

The picture is no better with new home sales. Here are the monthly changes over the last year.

Source: Census Bureau.

Note the great boom showing sales growth of more than 8 percent last March and almost 4 percent in April. This was followed by four consecutive months of declining sales. In short, we see big monthly movements, but no clear patterns.

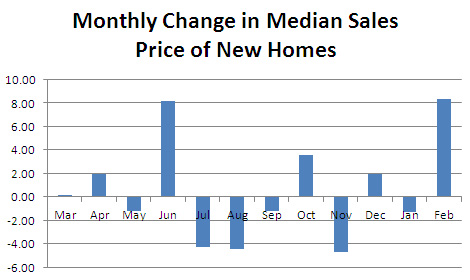

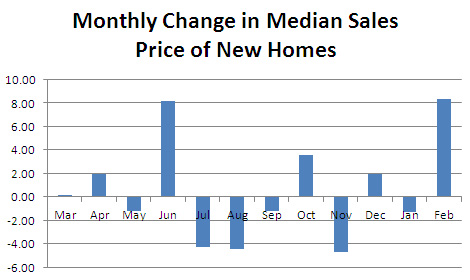

The same applies to the price of new homes.

Source: Census Bureau.

This one shows a huge 8 percent single month jump in prices last June, which was followed by two consecutive months in which prices fell by more than 4.0 percent. This series is even more erratic than the other three.

There are good reasons for expecting these series to be erratic. Factors such as the weather can play a huge role in the number of homes sold. In this case the monthly data might be telling us more about the state of the weather than the underlying market. While sales data (but not the price data) are seasonally adjusted, a milder than normal winter will have a substantial upward impact on the sales data.

The best rule of thumb is to see the monthly data as part of a longer trend. If a number is qualitatively different than the ones that proceeded it, most likely it is the result of random error, not a qualitative change in the market. This is especially true with the price data, in part because these series (unlike the Case-Shiller data) do not control for the mix of housing. This means that a reported price rise may be entirely due to the mix of houses being sold, not a higher price for each house.

Addendum: I have corrected earlier graphing problems.

The main thing that careful observers know from watching housing data over the years is that the monthly data should be largely ignored when assessing the housing market. The point here is that random factors have a large impact on monthly sales and price numbers, so that the noise often overwhelms the actual information about the housing market in a single month’s release.

To see the point, let’s start with existing home sales. The Realtors reported a small drop in February from an upwardly revised January number. This touched off a round of news stories about the weak state of the housing market. (The February sales number was higher than the unrevised number, meaning that it was higher than the level of sales that we had thought actually took place in January prior to the release.)

Source: National Association of Realtors.

Note that months where we see big changes in one direction are often followed and/or preceded by a big change in the opposite direction. For example, we could have been alarmed by the 3 percent falloff in sales last July, but then we would have been ecstatic over the 9 percent jump in August, only to be put in the doldrums by the 3 percent drop in September.

There is a similar story with month to month price changes.

Source: National Association of Realtors.

These data are even more erratic. The 8 percent one-month rise in prices in March must have seemed really exciting. On the other hand, the nearly 5 percent one-month drop back in January must have terrified people. Of course neither of these movements was likely real. These are just random fluctuations in the data.

The picture is no better with new home sales. Here are the monthly changes over the last year.

Source: Census Bureau.

Note the great boom showing sales growth of more than 8 percent last March and almost 4 percent in April. This was followed by four consecutive months of declining sales. In short, we see big monthly movements, but no clear patterns.

The same applies to the price of new homes.

Source: Census Bureau.

This one shows a huge 8 percent single month jump in prices last June, which was followed by two consecutive months in which prices fell by more than 4.0 percent. This series is even more erratic than the other three.

There are good reasons for expecting these series to be erratic. Factors such as the weather can play a huge role in the number of homes sold. In this case the monthly data might be telling us more about the state of the weather than the underlying market. While sales data (but not the price data) are seasonally adjusted, a milder than normal winter will have a substantial upward impact on the sales data.

The best rule of thumb is to see the monthly data as part of a longer trend. If a number is qualitatively different than the ones that proceeded it, most likely it is the result of random error, not a qualitative change in the market. This is especially true with the price data, in part because these series (unlike the Case-Shiller data) do not control for the mix of housing. This means that a reported price rise may be entirely due to the mix of houses being sold, not a higher price for each house.

Addendum: I have corrected earlier graphing problems.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT did a piece on Governor Mitt Romney’s pledge to impose tariffs on China to pressure it to lower the value of the dollar relative to the yuan. At one point it noted that many business people are opposed to this position:

“business leaders, while pressing for China to open its markets and protect intellectual property, caution that labeling China a currency manipulator could backfire, harming those efforts.”

It would have been worth a paragraph or two expanding on this point. There is a direct conflict in the interests of most workers and many businesses in U.S. policy toward China.

Financial firms like Goldman Sachs and Citigroup have a major interest in getting more access to China’s market. Firms with claims to intellectual property like Microsoft and Pfizer have a major interest in getting China to offer increased protection for their copyrights and patents.

By contrast, workers in the United States have a major interest in lowering the value of the dollar against the yuan. Since other countries would likely follow China in allowing their currencies to rise relative to the dollar (this is exactly what happened in 2005, the last time China had a large re-valuation of its currency), the result could be millions of new jobs in manufacturing. This would offer a large number of relatively good-paying jobs for less educated workers, putting upward pressure on the wages of these workers.

The Obama or Romney administration must decide which goals it will prioritize in its negotiations with China. If it makes more progress in getting access to China’s financial markets for Goldman Sachs and Citigroup or increased protection of Microsoft’s copyrights then it will make less progress in persuading China to raise the value of its currency.

Whoever is in the White House will have to decide which group’s interests are pursued and which group’s interests are downplayed. It would have been worth making this conflict more clear to readers.

The NYT did a piece on Governor Mitt Romney’s pledge to impose tariffs on China to pressure it to lower the value of the dollar relative to the yuan. At one point it noted that many business people are opposed to this position:

“business leaders, while pressing for China to open its markets and protect intellectual property, caution that labeling China a currency manipulator could backfire, harming those efforts.”

It would have been worth a paragraph or two expanding on this point. There is a direct conflict in the interests of most workers and many businesses in U.S. policy toward China.

Financial firms like Goldman Sachs and Citigroup have a major interest in getting more access to China’s market. Firms with claims to intellectual property like Microsoft and Pfizer have a major interest in getting China to offer increased protection for their copyrights and patents.

By contrast, workers in the United States have a major interest in lowering the value of the dollar against the yuan. Since other countries would likely follow China in allowing their currencies to rise relative to the dollar (this is exactly what happened in 2005, the last time China had a large re-valuation of its currency), the result could be millions of new jobs in manufacturing. This would offer a large number of relatively good-paying jobs for less educated workers, putting upward pressure on the wages of these workers.

The Obama or Romney administration must decide which goals it will prioritize in its negotiations with China. If it makes more progress in getting access to China’s financial markets for Goldman Sachs and Citigroup or increased protection of Microsoft’s copyrights then it will make less progress in persuading China to raise the value of its currency.

Whoever is in the White House will have to decide which group’s interests are pursued and which group’s interests are downplayed. It would have been worth making this conflict more clear to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post headlined an article on the release of existing homes sales data for February, “housing report disappoints as existing home sales dip in February.” It’s not clear why anyone would have been disappointed. The 4.59 million annual sales rate reported for February was below the 4.63 million rate now reported for January, but above the 4.57 million rate that had been reported before the revision.

Also, these monthly numbers are highly erratic. The difference between January and February numbers are well within any reasonable margin of error. The same is the case with the monthly price data. The fact that median price for February 2012 was 0.3 percent higher than the median price for February 2011 is virtually meaningless as this can easily be reversed with next month’s numbers, and in fact will be unless prices jump by 2 percent.

The Post headlined an article on the release of existing homes sales data for February, “housing report disappoints as existing home sales dip in February.” It’s not clear why anyone would have been disappointed. The 4.59 million annual sales rate reported for February was below the 4.63 million rate now reported for January, but above the 4.57 million rate that had been reported before the revision.

Also, these monthly numbers are highly erratic. The difference between January and February numbers are well within any reasonable margin of error. The same is the case with the monthly price data. The fact that median price for February 2012 was 0.3 percent higher than the median price for February 2011 is virtually meaningless as this can easily be reversed with next month’s numbers, and in fact will be unless prices jump by 2 percent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An NYT Economix blognote discussed a new paper by two economists (James Stock and Mark Watson) that purports to give us the bad news that we are likely to see a permanent slowdown in growth. Stock and Watson attribute this slowdown to a slower rate of growth of the labor force.

Before anyone gets too upset about the prospect of slower growth, it is worth reflecting for a moment on the different possible causes of slower growth. There are essentially four:

1) slower productivity growth;

2) higher unemployment or underemployment (involuntary);

3) slower population growth;

4) reduced labor force participation or hours worked.

The first two of these causes of slower growth are unambiguously bad. If productivity growth slows, then we are seeing less improvement in living standard for each hour we work. That is definitely bad news. However, nothing in the Stock and Watson paper suggests that productivity growth has slowed or will anytime soon.

I’ll come back to reason 2, but let’s look at reason 3 and 4 for a moment. Reason 3 is clearly true. Our population growth is slowing, as people are having fewer kids than they did in the 40s, 50s, and 60s. This means that we will have slower overall growth. However this could be associated with faster per capita growth. Each worker will now have more capital to work with, which could mean that they are more productive. Fewer people also means that there will be less strain on the infrastructure and the environment. In other words, if this is the reason why growth is slowing, there is no obvious cause for concern.

Reason 4 is a similar story but from a slightly different angle. Suppose people choose to retire early, take longer vacations, or have shorter workweeks. All of these practices would lead to slower growth, but it is hard to see anything negative in this picture. If people decide that they would rather work 10 percent less and have 10 percent less income, there is no reason that economists or anyone else should be upset. This also has the same benefits for the infrastructure and environment as the slower population growth noted above.

In short, if growth is expected to slow for reasons 3 and 4, as Stock and Watson argue in their paper, there is no obvious reason for anyone to be concerned. This is certainly not bad news. In fact it is arguable it is good news given the problem of global warming and other environmental concerns.

Finally, we have reason number 2, where growth slows because workers can’t get work. This is undeniably bad news, especially in a country like the United States where the support system for the unemployed is minimal. In fact, contrary to Stock and Watson, this is the main reason that growth has slowed since the downturn in 2007. There have been sharp declines in the overall employment to population ratio, but this drop has been concentrated among younger workers. These are not people who we could plausibly believe had opted to drop out of the workforce voluntarily.

The good part of the story is that we know how to restore growth to its former trend in this case: spend more money to create demand. Unfortunately, the politics are such that we are not likely to see this happen anytime soon.

An NYT Economix blognote discussed a new paper by two economists (James Stock and Mark Watson) that purports to give us the bad news that we are likely to see a permanent slowdown in growth. Stock and Watson attribute this slowdown to a slower rate of growth of the labor force.

Before anyone gets too upset about the prospect of slower growth, it is worth reflecting for a moment on the different possible causes of slower growth. There are essentially four:

1) slower productivity growth;

2) higher unemployment or underemployment (involuntary);

3) slower population growth;

4) reduced labor force participation or hours worked.

The first two of these causes of slower growth are unambiguously bad. If productivity growth slows, then we are seeing less improvement in living standard for each hour we work. That is definitely bad news. However, nothing in the Stock and Watson paper suggests that productivity growth has slowed or will anytime soon.

I’ll come back to reason 2, but let’s look at reason 3 and 4 for a moment. Reason 3 is clearly true. Our population growth is slowing, as people are having fewer kids than they did in the 40s, 50s, and 60s. This means that we will have slower overall growth. However this could be associated with faster per capita growth. Each worker will now have more capital to work with, which could mean that they are more productive. Fewer people also means that there will be less strain on the infrastructure and the environment. In other words, if this is the reason why growth is slowing, there is no obvious cause for concern.

Reason 4 is a similar story but from a slightly different angle. Suppose people choose to retire early, take longer vacations, or have shorter workweeks. All of these practices would lead to slower growth, but it is hard to see anything negative in this picture. If people decide that they would rather work 10 percent less and have 10 percent less income, there is no reason that economists or anyone else should be upset. This also has the same benefits for the infrastructure and environment as the slower population growth noted above.

In short, if growth is expected to slow for reasons 3 and 4, as Stock and Watson argue in their paper, there is no obvious reason for anyone to be concerned. This is certainly not bad news. In fact it is arguable it is good news given the problem of global warming and other environmental concerns.

Finally, we have reason number 2, where growth slows because workers can’t get work. This is undeniably bad news, especially in a country like the United States where the support system for the unemployed is minimal. In fact, contrary to Stock and Watson, this is the main reason that growth has slowed since the downturn in 2007. There have been sharp declines in the overall employment to population ratio, but this drop has been concentrated among younger workers. These are not people who we could plausibly believe had opted to drop out of the workforce voluntarily.

The good part of the story is that we know how to restore growth to its former trend in this case: spend more money to create demand. Unfortunately, the politics are such that we are not likely to see this happen anytime soon.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT began an article discussing a “right to work” measure in Minnesota by describing it as a “measure … that would allow workers to avoid paying fees to unions they choose not to join.” It would have been helpful to remind readers that under federal law a union is legally obligated to represent all the workers in a bargaining unit regardless of whether or not they choose to join the union.

This rule means that workers who do not join the union not only gain from whatever wage and benefit increases the union negotiates with the employer, they also are entitled to the union’s representation in any disputes that are covered under the contract. For example, if the employer wants to discipline or fire a worker who is not a member of the union, the union is obligated to represent this worker in the same way as if they were a dues paying member of the union.

In this context, the Minnesota measure means that workers who support a union can effectively be required to pay for the representation of workers who do not support the union. This is not an obvious step toward promoting individual freedom.

Contrary to what the article asserts, every worker in Minnesota can already “avoid paying fees to unions they choose not to join.” They have the option to not work at a company where there is a union contract that requires workers to pay for their union representation.

This measure is about taking away rights, not extending them. If it were approved, workers would no longer have the right to sign a contract that required that everyone who benefited from union representation paid for this representation. This is a case of the government interfering with freedom of contract.

The NYT began an article discussing a “right to work” measure in Minnesota by describing it as a “measure … that would allow workers to avoid paying fees to unions they choose not to join.” It would have been helpful to remind readers that under federal law a union is legally obligated to represent all the workers in a bargaining unit regardless of whether or not they choose to join the union.

This rule means that workers who do not join the union not only gain from whatever wage and benefit increases the union negotiates with the employer, they also are entitled to the union’s representation in any disputes that are covered under the contract. For example, if the employer wants to discipline or fire a worker who is not a member of the union, the union is obligated to represent this worker in the same way as if they were a dues paying member of the union.

In this context, the Minnesota measure means that workers who support a union can effectively be required to pay for the representation of workers who do not support the union. This is not an obvious step toward promoting individual freedom.

Contrary to what the article asserts, every worker in Minnesota can already “avoid paying fees to unions they choose not to join.” They have the option to not work at a company where there is a union contract that requires workers to pay for their union representation.

This measure is about taking away rights, not extending them. If it were approved, workers would no longer have the right to sign a contract that required that everyone who benefited from union representation paid for this representation. This is a case of the government interfering with freedom of contract.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan is supposed to be a brave and serious thinker. That’s how the Washington punditry treats him. Last year, the Peter Peterson gang gave Ryan a “Fiscy Award” for “leading the way in promoting fiscal responsibility and government accountability.” Politico made Representative Ryan its “health care policymaker of the year.” Ryan is a regular guest on the Sunday talk shows and he can always count on a warm reception from the very serious people.

For this reason when Representative Ryan again proposed a budget that would shrink non-defense spending outside of Social Security and health care programs to zero by 2050 the proposal deserves real attention. According to the projections of the Congressional Budget Office (Table 2), Representative Ryan’s budget would shrink the category of defense and non-defense discretionary spending, plus non-health entitlements to 3.75 percent of GDP by 2050.

Since Representative Ryan has said that he wants to keep military spending near its current level of 4.0 percent of GDP, this would leave no money to pay for the Justice Department, the Food and Drug Administration, Education, the National Institutes of Health or anything else that the government does.

This shrinking of non-defense spending to zero was also in Representative Ryan’s budget last year, however he could have been credited with an honest, if incredibly foolish, mistake. However he has now gone on record with the same proposal in 2012, presumably indicating that this budget does in fact reflect his views and the views of the Republicans in the House, if they again approve the budget, as they did last year.

It is remarkable that this extraordinary proposal by Representative Ryan has not gotten more attention from the people who think so highly of him in official Washington. Apparently they consider the elimination of most of the government to be a very reasonable suggestion.

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan is supposed to be a brave and serious thinker. That’s how the Washington punditry treats him. Last year, the Peter Peterson gang gave Ryan a “Fiscy Award” for “leading the way in promoting fiscal responsibility and government accountability.” Politico made Representative Ryan its “health care policymaker of the year.” Ryan is a regular guest on the Sunday talk shows and he can always count on a warm reception from the very serious people.

For this reason when Representative Ryan again proposed a budget that would shrink non-defense spending outside of Social Security and health care programs to zero by 2050 the proposal deserves real attention. According to the projections of the Congressional Budget Office (Table 2), Representative Ryan’s budget would shrink the category of defense and non-defense discretionary spending, plus non-health entitlements to 3.75 percent of GDP by 2050.

Since Representative Ryan has said that he wants to keep military spending near its current level of 4.0 percent of GDP, this would leave no money to pay for the Justice Department, the Food and Drug Administration, Education, the National Institutes of Health or anything else that the government does.

This shrinking of non-defense spending to zero was also in Representative Ryan’s budget last year, however he could have been credited with an honest, if incredibly foolish, mistake. However he has now gone on record with the same proposal in 2012, presumably indicating that this budget does in fact reflect his views and the views of the Republicans in the House, if they again approve the budget, as they did last year.

It is remarkable that this extraordinary proposal by Representative Ryan has not gotten more attention from the people who think so highly of him in official Washington. Apparently they consider the elimination of most of the government to be a very reasonable suggestion.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión